|

| "I believed in all those square values...loyalty, fidelity." |

At a friend's urging, I remember going to see the then-popular student-protest movie, The Strawberry Statement (1970) and being somewhat taken aback (even at 13 years of age) that in this film about counterculture revolutionaries, the only jobs these shake-up-the-system extremists could devise for women was to fetch food and work the copy machine! With few exceptions, women in the films of the New Hollywood were depicted as either sexually available embodiments of the "free love" movement or killjoy symbols of marital conformity.

Small wonder then, that Diary of a Mad Housewife stood out from the crowd. Here was a film that was a serious, considered look at America

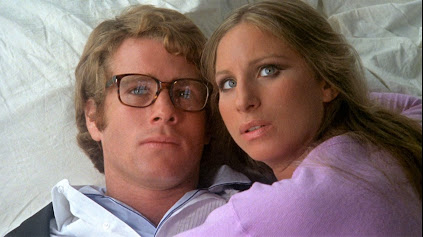

The couple in question: Tina and Jonathan Balser. She, an educated, family-focused housewife, he, a socially ambitious young lawyer. They have two children and live in an 8-room apartment across from Central Park . Is it just coincidence that their lives are exactly the lives Rosemary & Guy Woodhouse aspired to in Rosemary's Baby? (Minus, of course, that nasty little business with the Devil.)

|

| Carrie Snodgress as Tina Balser |

|

| Richard Benjamin as Jonathan Balser |

|

| Frank Langella as George Prager |

Oh, and Tina thinks she's going mad. Why?

|

| Frannie Michel as Liz Balser / Lorraine Cullen as Sylvie Balser |

Eve Arden in Mildred Pierce - 1945

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

It all sounds pretty heady and serious, but Diary of a Mad Housewife is actually brilliantly funny. The film's offbeat balance of social commentary and dark character humor is established in the wonderful, pre-credits opening sequence. It's like a tragi-comic burlesque of 20th-century marriage as envisioned perhaps by Valerie Solanas in her SCUM Manifesto (remember her? She's the radical feminist who shot Andy Warhol in 1968). In the space of 10 minutes, Richard Benjamin heaps what seems like an entire lifetime's worth of complaints and criticisms on the head of the mutely tolerant Snodgress as they go about their morning rituals. You sense somehow that this is a "new side" of her husband Snodgress is seeing (in the novel by Sue Kaufman, an unexpected inheritance is the catalyst for Jonathan's sudden obnoxious turn) and her strained attempts to hold it together in the face of the onslaught is like a sly feminist take on the "Plastics!" party scene in The Graduate.

It's no wonder that everyone was hailing Carrie Snodgress as the new star of the '70s when Diary of a Mad Housewife was released. She was an original. Her unadorned naturalism, husky voice, and air of self-assured "smarts" made her a welcome relief from all the well-intentioned bimbos (Karen Black cornered that market) and lost waifs (Liza Minnelli) littering the movie landscape. Her performance here is a delight of small details. Check out the catalog of emotions she conveys in the party sequence when she meets up with Langella for a second time. She's absolutely fun and fascinating to watch. Carrie Snodgress never chased the stardom that was hers for the taking, and when she passed away in 2004, cinema lost one of its best.

As its title suggests, Diary of a Mad Housewife is told exclusively from Tina's perspective. And, as she is admittedly going mad (the film we're watching is actually Tina's disclosures to an encounter group) she is the quintessential unreliable narrator. In taking such a precise point of view, the film reminds us that we are seeing the world as Tina sees it, not necessarily as it really is. Richard Benjamin's broad-strokes caricature of the modern FDM (Forceful Dominant Male) is a lot easier to take under these circumstances.

Diary of a Mad Housewife came out at the height of the Women's Liberation Movement, which may explain why so many critics at the time expressed disappointment in the perceived passivity of the Carrie Snodgress character. Half felt the film amounted to little more than male-bashing, stacking the deck to make Snodgress the guiltless victim. Others complained that Snodgress' inaction in the face of so much abuse rendered her an anti-feminist heroine and only added another docile female character to the ranks of cinema leading ladies.

Both arguments have some validity, but seeing the film today, I'm actually grateful Diary of a Mad Housewife showed so much restraint. It has a lot on its plate, culturally speaking, but it never becomes a preachy polemic on feminism and always remains a character-fueled comedy/drama. I'm reminded of those awful final seasons of that TV sitcom Designing Women when the show took on an air of self-importance that had each show ending with a character serving as the mouthpiece for the creators' political views and launching into some windy monologue. Mercifully Diary of a Mad Housewife avoids that fate.

A group therapy member after Tina has told her tale of upscale angst:

"I joined 'group' with the understanding that I would get help with my very real and terrible life's problems. She has a husband AND a lover AND an 8-room apartment on the Park!?! Why does SHE need help?"

|

| Yuppie Ennui |

"I joined 'group' with the understanding that I would get help with my very real and terrible life's problems. She has a husband AND a lover AND an 8-room apartment on the Park!?! Why does SHE need help?"

Diary of a Mad Housewife, a very funny and perceptive female alternative to all those 70s male-angst movies. It skillfully sidesteps becoming a single-minded political indictment of male oppression and chauvinism, and remains a look at one woman faced with her own inability to make anything meaningful of her existence. Tina isn't socially conscious, repressed, or even oppressed. She's too smart for that. She is incredibly lucid about the absurdity of the life her husband seems intent on pursuing, and, when she's really feeling attacked, she has a mouth on her and a quick, biting wit that gives as good as she takes.

No, Tina's problem stems from having lost her way in her pursuit of the American Dream (in this instance, home, family, and loving husband) and her questioning of the values she grew up believing in. Drifting into a pseudo-masochistic affair with a man arguably as insensitive as her husband, she finds little comfort and certainly no answers. In her own way, she's as spiritually adrift as the bikers in Easy Rider. |

| "I'm just a human being." |

Copyright © Ken Anderson

.jpg)