“Life

is never quite interesting enough, somehow. You people who come to the movies

know that.” Shirley

Booth as Dolly Levi in The Matchmaker (1958)

No truer words were ever spoken on the topic of what movies

mean to us “dreamers.” I, like a great many film buffs (and as the title of

this blog reiterates), am a dyed-in-the-wool dreamer. And for as long as I can

remember, the allure of motion pictures for me has been their intrinsic link to the

fundamental human need to dream, to long for, to imagine, to aspire to, and to

hope.

Because

I’m essentially an impractical, head-in-the-clouds fantasist for whom dreams

have often proved a contradictory source of my greatest joys and deepest sorrows; I've always been intrigued by the curiously dual nature of dreaming. Dreams are inarguably at the root of all human ambition and invention, possessing the power to ease spiritual pain by way of escapism, inciting creativity, and spurring on the imagination to all manner of human achievement. Yet

at the same time, dreams are equally prone to sowing seeds of dissatisfaction...fostering discontent and delusion when they create a hunger and desire for

things that can never be attained.

When I think about it, a great many of my favorite novels seem to be about the pernicious nature of idealism and dreams: F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Gustave Flaubert’s

Madame Bovary, Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust, and,

apropos of this post, Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie and An

American Tragedy. Dreiser being specifically

the author I find to be the most compelling purveyor of narratives sensitive to

the healing/hurtful siren song that is the myth of The American Dream.

|

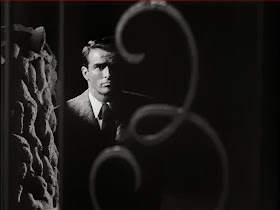

| Montgomery Clift as George Eastman |

|

| Elizabeth Taylor as Angela Vickers |

|

| Shelley Winters as Alice Tripp |

A Place in the Sun is the story of George Eastman (Clift), the poor-relation nephew of pillar-of-society industrialist Charles Eastman, who flees a dead-end

bellhop job in Chicago to be taken on as a worker in his uncle’s bathing suit

factory. George is haunted by his stiflingly poor, rigidly religious

upbringing, and is driven—to an almost pathological degree—to overcome the

limitations of his meager education and humble origins. Applying considerable

initiative toward his ambitions (evinced by his taking home-study courses and

devising plans for factory efficiency in his spare time) George appears at first resigned, albeit restlessly, to work hard for his modest piece of the American Dream. But

as bedeviled as George is about his impoverished past, it soon becomes clear that he is

equally consumed with the desire for the kind of brass ring life his Eastman

lineage dangles teasingly just beyond his grasp.

|

| Locked Out George Eastman stands dejectedly outside the gate of his uncle's estate, Charles Eastman. The large, ornamental "E" on the gate serving as a caustic reminder of a birthright denied |

Ultimately, fate deals George an ironically cruel hand when the realization of all of his ambitions and dreams become certainties (his professional advancement and social acceptance coincide with a blossoming romance with the beautiful and glamorous socialite, Angela Vickers [Taylor]) at the very moment news of his impregnation of Alice, the plain-but-sweet factory co-worker (Winters) just as certainly signals the end to all he has ever hoped for.

While An American Tragedy (both the novel and the original 1931

film, which is said to be the most faithful adaptation) posit George’s dilemma

within the parameters of a sociopath’s conundrum: George, not feeling much of

anything for either girl, weighs the most selfishly advantageous outcome and

plots to rid himself of the problematic pregnant girlfriend. A Place in the

Sun’s intentionally romanticized construct encourages the viewer to sympathize/identify with George’s predicament. A device that ultimately (and

provocatively) implicates us in the tragic turn of events as they play out.

|

| "The reason they call it 'The American Dream' is that you have to be asleep to believe it."

George Carlin

|

Theodore Dreiser's pre-Depression era novel An American Tragedy sought to address the accepted American belief that hard work equaled affluence and advancement in a country where nepotism, bloodlines, and arbitrary class/social hierarchies impose distinct limitations. A Place in the Sun uses the false promise of post-war American prosperity as the bait that lures dreamers like George Eastman into believing "the good life" is his for the taking.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

A common complaint leveled at A Place in the Sun is that the tension of the film’s central

conflict is significantly weakened in having the drab and ultimately annoying Shelley

Winters character rendered as such a blatantly unappealing option to the

dream-girl perfection of Elizabeth Taylor. The implication being, I suppose, is

that if given the opportunity, anyone in his right mind is going to try to

drown the sympathetic but whiny Winters if it will help land them the exquisitely

beautiful, sweet-natured (and let’s not forget, loaded) Elizabeth Taylor. If

that’s true, what does that say about us?

The near-identical beauty of Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor emphasizes their compatibility

|

Therein lies my fascination with A Place in the Sun. Instead of turning Dreiser’s novel into just another

crime story with a social commentary overlay, George Stevens—drawing upon the

entire arsenal of cinematic devices that helped give Hollywood its reputation as

America’s “Dream Factory”—idealizes the tale and subtly seduces, making us complicit

allies in George’s social-climbing fantasies. He structures the film as an

unabashedly romanticized, male Cinderella fairy tale about “fated to be mated” lovers

threatened by the ugly specter of poverty and deprivation. The latter is embodied

by the likable but difficult-to-root-for Shelley Winters.

With every lovingly-photographed close-up of the impossibly beautiful couple…with every lushly orchestrated romantic idyll captured in passionate tableau…we’re not only encouraged to project our fantasies onto the idealized couple, but to see them as sympathetic souls deserving of having their dreams come true. Something not possible without vilifying the story’s real victim (Winters) as the sole obstacle to their happiness.

With every lovingly-photographed close-up of the impossibly beautiful couple…with every lushly orchestrated romantic idyll captured in passionate tableau…we’re not only encouraged to project our fantasies onto the idealized couple, but to see them as sympathetic souls deserving of having their dreams come true. Something not possible without vilifying the story’s real victim (Winters) as the sole obstacle to their happiness.

The genius of A Place

in the Sun, and why I consider it to be a minor masterpiece, is how,

through the juxtaposition of appealing images of wealth and dreary images of

poverty, the audience, when faced with the issue of what to do about the blameless

but problematic Shelly Winters character, are placed in the same morally

ambiguous position as Montgomery Clift.

PERFORMANCES

Only two of the 9 Oscar nominations A Place in the Sun garnered in

1951 were in the acting categories: Best Actor, Montgomery Clift, and Best Actress Shelley Winters (it won a whopping 6 awards, including Best Director for

Stevens). The always-impressive Clift brings a heartbreaking vulnerability to

what I think is one of his best screen performances. At no moment do you ever

feel he is being moved forward by the plot. You can see every thought and

motivation play out on his face.

On A Place in the Sun’s

DVD commentary track, much is made of the fact that in taking on the role of

the mousy Alice Tripp, blond bombshell Shelley Winters astounded audiences by

so playing against type. Winters is, indeed, very good, but if you’re like me

and largely unfamiliar with the work of Shelley the sexpot, her role feels right in step with characters she played in a great many of her latter films (1955s The Night of the Hunter comes to mind), and thus her performance doesn't feel like the huge departure it perhaps once did.

If your goal is to make plausible the notion that an otherwise sane man would resort to murder for the love of a woman, you're definitely on the right track if that woman is then 17-year-old Elizabeth Taylor. What a knockout! Overlooked by the Academy, her performance in A Place in the Sun is rather remarkable. She gives a surprisingly mature performance—one of her best, in fact—proving to be particularly effective in her later scenes. Taylor would work again with director George Stevens in Giant (1956), and the truly bizarre misfire, The Only Game in Town (1970).

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

My deep affection for A Place in the Sun extends to the way it uses romantic imagery to convey the illusory allure of desire and longing. And by illusory allure, I mean that dreams are only pleasant when they hold out the possibility of coming true. To want for something you can't have tears you apart.

|

| George is frequently photographed surrounded by idealized images of success and wealth |

|

| Like the beckoning light on Daisy's dock in The Great Gatsby George studies high school classes under the flickering neon reminder of the Vickers family fortune |

(Above) "Ophelia", John Everett Millais' mid-19th Century painting depicting the drowning death of Shakespeare's heroine, looms ominously over George's head (below) as he ponders: how do you solve a problem like Alice Tripp?

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

A Place in the Sun is one of those rare screen adaptations of a beloved book that captures the author's intent even though it plays fast and loose with the original text. Theodore Dreiser's 1925 novel was turned into a Broadway play in 1926, and a film by Josef von Sternberg in 1931 (for which it is said Dreiser didn't care). Screenwriters Michael Wilson and Harry Brown adapted the 1951 film, and while faithful adaptations are fine, I love when collaborators are able to stay true to the feel of an artist's work, even when its superficial form has been altered. George Stevens has created a forcefully cinematic film that tells its story with a language all its own. It's beautiful to look at, wonderful to listen to (the Franz Waxman score is a real highlight), and boasts a slew of first-rate performances. It's a near-perfect film.

Near perfect...

Near perfect...

Although Raymond Burr, cast as the prosecuting attorney, is actually fine (I guess. It's the same performance he's given for decades), his close association with the Perry Mason character proves a big distraction to me. When he shows up, this absolutely breathtakingly engrossing romantic drama suddenly becomes a TV program.

Similarly, and due to no fault of the actor himself, the casting of Paul Frees as the priest during the film's pivotal final minutes just sticks in my craw. Why? Because as I child, I watched Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color on TV for years. Anyone familiar with the show will recognize Frees' distinctive voice as the narrator of a million Disney documentaries. And as he is also the voice of the Ghost Host at Disneyland's Haunted Mansion, every time he speaks I'm thrust out of the narrative. Frees' voice is waaaay too hardwired with Disney associations to work on any level for me. Given that he's also the voice of animated no-goodnick Boris Badenov (whom I adore), I suppose I should just be thankful Frees never resorts to speaking in a Pottsylvanian accent.

Watching A Place in the Sun is an immensely pleasurable experience that satisfies no matter what aspect of its story you choose to focus on: the romance, the social commentary, the crime drama, or, my personal preference, the melancholy discourse on the failings of the American Dream. If you haven't seen A Place in the Sun in a while, it's definitely worth another look. If you've never seen it before, well, prepare to be swept away. I am...every time I see it.

Clip from "A Place in the Sun"

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 -2013

Thank you so, so much for posting this.

ReplyDeleteA Place In The Sun is one of my absolute favorites for so many reasons. Elizabeth Taylor gives one of her greatest performances (remarkable, considering her age) as does Montgomery Clift.

What breaks my heart about the film is no matter how many times I watch it, I hope that things will work out differently. I already know the ending - the untimely end of Alice, the imprisonment of George and the devastation of Angela. But when George & Angela are vacationing, photographed smiling in the paper, there is that tiny part of me that thinks they might live happily ever-after before the plot takes its sudden turn. But then you're absolutely right, I (like the rest of the audience) feel placed in the morally ambiguous position over what to do about Alice. (I'd drop her for Elizabeth Taylor's love and money, which makes me question my morality something shocking!)

Watching the film so many times and still hoping it might end differently ... to me is a testament of the magic of film. It plays right to your heart, it captures a bundle of your emotions and makes you question everything you think you know already.

Thank you again for posting :)

- Mitchell

Also note the fact that the intimate moments and conversations between George and Alice are filmed in darkness. The cinematography of these scenes is absolutely stunning. I also love the conversation between the two in the diner. Alice tells George that she has revised her opinion about his being a typical Eastman, And what is the point of it anyway she adds. Rich people and pretty girls in nice clothes - she refers to the superficiality of it all. At that point I sensed that George feels put down. He knows in his heart that this superficial world is the one he wants to belong in - remember the 100,000 dollar checque he sees on the room where he first talks to his uncle over the phone after arriving in New York. I also like the way George is portrayed as being very earnest, perhaps even slightly stupid. He is an interesting combination of ambition, naivete, stupidity, sensuality and of course verging on amorality.

DeleteTheodore Dreiser was an excellent writer. I also highly recommend Carrie directed by William Wyler. The film is based on the Dreiser's Sister Carrie. The ending of the film is different to that of the book. The film features Jennifer Jones and Laurence Olivier - the latter at his very best.

"Carrie" is one of my favorites, and having just posted a clip from it on my YouTube channel, it's very fresh in my mind. I read the book before the film, and was impressed by how it still managed to keep the tone of the story while having to whittle it down so much.

DeleteDreiser is among my top fiver favorite authors.

And those are great observations about how the character of George is portrayed aspects of his paradoxical personality are conveyed in "A Place in the Sun" ... certainly a considerably more sympathetic take than Von Sternberg's "An American Tragedy."

Thanks again for your thoughtful comments and taking the time to share them.

Hi Mitchell

ReplyDeleteUntil reading your terrifically astute comment, It hadn't actually occurred to me, but I engage in the exact same kind of fruitless hope each time I watch "A Place in the Sun" as well!

I love that you become so invested in the story and the fates of its characters to find yourself wishing a better outcome for them every time you watch the film!

Your response to "A Place in the Sun" is one of a romantic, and i think it is a testament to the soundness of George Stevens' vision that, even after seeing it many times, the film plays "Right to your heart."

Thank you for your comment, which is so much from the perspective of someone passionate about films (this one, anyway), that it reads like an addendum to this post. Wonderful to have you share your personal fondness for this masterful film!

Very perceptive commentary. Enjoyed reading it. This has always been on my list of much watch films. In fact I have always been obsessed by it. So many tiny, clever details that speak volumes.

DeleteThe film George Eastman goes to watch (where he runs into Alice Tripp his co-worker by accident) is Now and Forever. The now will have repercussions that will last forever. Nice touch.

Later on in the film the morning after George and Alice have spent the night together the uncle visits the shop floor. He decides to give George a promotion and walks over to him. In this scene George turns his back to Alice as he shakes his uncle's hand. Nice. Stevens was indeed a master.

The chemistry between Clift and Taylor was electric and the physical desire palpable. It had to be real and the story goes that it indeed was. Liz Taylor went on record saying that the iconic dance scene was a dance of sex; a minuet of the glands. She had received her first real-life kiss just two weeks before but the kiss with Monty was far more exciting. The director did not tell her what to do. She kissed Clift instinctively. She also said that both she and Clift felt aroused during the scene even though they were only acting. - they really inhabited their characters. And she was proud that she made Clift that way - it was a testament to her acting skills.

Shelley Winters said that the rest of the cast who watched the filming of the scene were convinced that the two were romantically involved. Taylor's performance in this film was so shaded and tender - her best acting turns bar none. As she always said Clift made her a better actress. She realized that before this film she had been playing with toys. Clift's ability to immerse himself in his role inspired her.

Taylor and Clift were very much in love although Clift at that point was decidedly gay and went only so far. They probably never had a full-fledged affair but there was a strong romantic element to it and the lines between platonic friendship and sexual attraction were somewhat blurred. Taylor would have willingly married him. In fact I think they were the loves of each others lives. The situation was impossible and it was in many ways an unrequited romance. Art imitating life.

After the sparks had died down and after Clift finally admitted to her that he was gay the two became close friends for life.

Thank you very much.

DeleteI enjoyed reading about your fondness for this movie and you've given me several new things to look for the next time I watch this.

Since posting this essay I finally had the opportunity to see "An American Tragedy" (1931) and was so impressed with how different the same story can be told by two different directors/screenwriters. Two such different yet magnificent films.

I agree with you that George Stevens is a master filmmaker, and while it seems you and I have read the same memoirs and stories about the making of this film, your enthusiastic and knowledgeable contribution to this post is just the sort of thing readers often tell me that they most enjoy about the comment section of this blog.

Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts on our mutual favorite, "A Place in The Sun."

Hi, Ken. I really enjoy your blog.

ReplyDeleteI just wanted to make a comment about the famous party dress that the great Edith Head designed for Angela (Taylor) to wear when she meets George (Clift) for the first time in the billiard room.

Although it was actually a pale yellow, on black and white film it shows up as radiantly white and appears almost bridal. Head's design basically became the standard for party and prom dresses for the rest of the decade. In the film "Back to the Future," for example, most of the girls (including Lorraine) are wearing variations of the same dress at the high school dance.

With it's sweetheart neckline, cinched waist and the billowing A-line skirt, it created an hourglass figure and even allowed for some bare shoulders and cleavage. But the fullness of the skirt made of tulle and taffeta kept it sweet and gave it an air of romance.

I suppose all of the teenage girls hoped that they could look a little like Elizabeth Taylor if they had the same dress. I am pretty sure no one came close.

- Paul

P.S.: This movie is so good, it almost makes you believe that Shelley Winters could be drowned. But I saw "The Poseidon Adventure." She knows her way around the water.

Hi Paul John

DeleteThank you very much! I had read and heard a great deal about the popularity of Taylor's prom dress, but I never knew it was yellow! I never saw "Back to the Future", but I saw a great many mid-50s teenage rock and roll pictures on the Late Late Show, and you can definitely see this film's influence. Each prom scene is a sea of strapless gowns with full skirts. Thanks for mentioning the dress, for it has grown as iconic as the film itself.

Whenever I hear arguments about movies not influencing .public behavior (usually on the topic of violence), I always have to smile. Not only in the instance of Edith Head making every teen girl think she could look like Taylor, but movies have been influencing public behavior since the days when the mere sight of a shirtless Clark Gable in "It Happened One Night" almost ruined the men's undershirt business back in 1934.

brought the men's undershirt.

And yes, as Winters proved in "The Poseidon Adventure"- "In the water, I'm a very skinny lady!"

Thanks very much for sharing your film knowledge!

What I really love about this post is your catching the Ophelia portrait on the wall behind Clift! That is very interesting. I love subtle symbolism/foreshadowing like that in the movies!! I suppose she was lucky he didn't have a picture of Joan of Arc or Marie Antoinette on the wall......

ReplyDeleteOf, thanks, Poseidon. But I can't really take credit for that. George Stevens' son brings it up on the DVD commentary, and I found it such a fascinating example of the care with which this film was made, that I wanted to call attention to it as well. All the more so because "A Place in the Sun" is a film I've easily seen about 15 times or so, and I never once noticed it! Like you, I love when films do things like that. A bad director would have done a cutaway to it, or zoomed to a closeup. I like when a filmmaker puts things in a movie that are important to the story, but that perhaps not everyone is going to catch.

Delete(Like your comment about alternative artwork that could have adorned George's apartment!) Thanks, Poseidon!

One of the great, great films. Shelley Winters, Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor are utterly compelling every time I see it again.

ReplyDeleteEchoing runningtool (Mitchell's) marvel at Elizabeth Taylor's performance despite being so young...she had already proven herself a natural photogenic beauty with natural-born star quality, but she also had innate instincts as an actress already capable of passion, depth and subtlety. Because she was so young and beautiful, she had to wait years for the meatier roles to come her way, even though talent-wise she was already prepared to handle any part she chose to tackle.

In fact it was not until Giant five years later (also with Stevens) that Taylor was able to begin to display her true range...and by the late 50s she was a perennial best actress Oscar nominee. I never begrudge her that first Oscar for Butterfield 8 in 1960, even though she always called it her sympathy prize for almost dying of pneumonia...her performance in that is pretty damn fierce!

As she matured, Elizabeth's performances just continued to get better and better, culminating in her unforgettable Martha in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, and continuing with fare as varied as Kate in Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew, quirky "pre-indie" parts like Zee in X, Y and Zee, her scream queen horror turn in Night Watch, multiple characters in The Blue Bird, Louella Parsons in that TV movie...real character parts that she always aced like a pro.

I do think that Taylor's looks were as much of an obstacle to her doing more acting in later years, too...who wants to be constantly compared to an earlier, more beautiful, slimmer self, rather than judged on the performance itself?

I do think that if Elizabeth Taylor had been just a little less attractive, she would have astounded us in far more great films. Thank goodness we do have quite a few to enjoy like this one--and that this goddess was able to grace us with both unearthly beauty and dynamic talent!!

Ken, great story as always and the pictures you found are amazing as usual.

-Chris

Hi Chris

DeleteGlad to hear this is a favorite of yours as well. All you say about Taylor is true. I think she was always a little underrated because of her looks and tabloid-friendly private life, but she really took more risks as an actress than most of her stature (as much as I love Doris Day, I always regret her marriage to her "image"). A flop is to be expected here and there, but Taylor was always fascinating. Her work here gets better with each viewing (I loved how on a recent TCM screening, the host asked us to call attention to her fainting scene. calling it one of the best screen faints of all time.) Thanks Chris, for the kind words, and glad you liked the screencaps!

I really liked your post and really thought you made a great point about how the film seduced us into complicity with George's criminality. It's a provocative way of looking at the film. Even Pauline Kael mentioned how Shelly Winters' death seemed like a mercy killing because Stevens had made her so annoying.

ReplyDeleteHowever, I have to confess that the film's overwhelmingly romantic imagery is what bugs me about it and leaves me cold. It worships material wealth and beauty and the upper-class life as the ultimate Good; and I think Stevens really doesn't undercut that; I'm not aware of a point where the viewer is made to sit up and think, ye gods, what have I been sympathizing with? That said, I also have to say that I've never really gotten the feeling from reading Paradise Lost that we're NOT supposed to sympathize with Satan. I think Milton was a little confused there.

I've seen Shelly Winters in some of her early bombshell roles (eg, 'A Double Life'), and, yes, she's really the same. She may look bosomy and beddable, but she still has that whiny Brooklynese finish to her speech. It's a little distracting, especially when she worked in period pieces. And you're right, no one can listen to Paul Frees with his hollow, booming voice; no matter the occasion, it sounds like he's getting ready to make a public service announcement.But for Boris Badenov's sake, I can forgive him.

Terrific point about how the film's point of view on wealth and all the things George Eastman so covets. In fact, it's a quite marvelous one, because I really don't believe Stevens thinks what George covets is valueless. At least that's not the sense I get.

DeleteEvery aspect of non upper-class life is presented as drudgery and dullness. As one who (for better or worse) has always identified with the character of George, I would like to think that Elizabeth Taylor and all that her life represents is but a symbol of that vague thing called "The American Dream", and that we're invited to question not the value of the dream itself, but the lie which says it is within our grasp if we only work hard enough for it.

I have to say your perspective is even more food for thought in a film that provides ample.

I love your description of Shelley Winters, and the words you chose to characterize Frees' voice is dead on the mark! It made me laugh...especially the Badenov reference. Thanks for a marvelous comment,GOM!

But she was from St. Louis.

DeleteShelley's family moved from St. Louis, MO. to Brooklyn, NY when she was three-years-old.

DeleteGreat read on A Place In The Sun...it's a perennial favorite of mine.

ReplyDeleteWhat's also remarkable about Elizabeth's performance is that Taylor is a dozen years younger than her co-stars Clift and Winters, who also had stage experience. ET holds her own and then some, plus viewers never notice the age difference.

As for Winters, Shelley wasn't really making much headway as a blonde bombshell, and Stevens really opened the door to Winters' remarkable star actress career by playing the coarse but goodhearted working girl...

Thanks, Rico!

DeleteElizabeth's Taylor's age in relation to her co-stars hadn't really occurred to me. In fact, she and Clift have always seemed like contemporaries to me. Your observation further confirms how exceptional she is here.

And your comment about Shelley Winters is in line with what another commenter referenced. I think you're right in Stevens being instrumental in moving her career in another director.

Glad to hear this film is a favorite , and I appreciate your taking the time to comment!

I've always enjoyed this movie without ever really believing a single word of it. Money and social position are everything in American society, but good looks aren't very far behind, and it's impossible to think that Montgomery Clift could walk into a living room without everyone there going "Holy Shit! Who the hell is THAT?" Even if his Uncle still put him to work on the assembly line, he would have been absorbed into their social circle immediately. Likewise, the idea that he would succumb to Shelley Winters after first gazing on Elizabeth Taylor strains all credulity. He would be hellbent on climbing the ladder with no distractions.

ReplyDeleteI think a lot of the stuff about Shelley Winters image changing role was kind of Hollywood PR. In her first major role in A DOUBLE LIFE, she played a working class waitress who gets strangled by crazy actor Ronald Colman as he rehearses "Othello." in LARCENY she's a gangster's sleazy moll, shot in the finale. And of course she's run over by a car as Myrtle in the Alan Ladd version of THE GREAT GATSBY. She's also low key and a little drab in the classic 1950 western, Winchester 73.

Ha! Yes, I know what you mean about Clifts' stunning good looks, and it's an interesting perspective you introduce...on two levels.

DeleteFrom the cinematic perspective, I've always felt Clift's crushing good looks played into making the audience somewhat complicit in the narrative conflict and exposes an notion that we harbor as a culture: that the attractive somehow "deserve" better. If George Eastman was played by an average-looking actor like John Garfield, I think the viewer would more readily side with the opinion that he's a heartless social climber and should return to Winters.

Clift looks like he belongs with that crowd, and by extension, I think the audience has a moral slip in feeling that, yes...he deserves it.

I liken it to real-life situations in which one encounters an uncommonly beautiful man or woman as a waiter, clerk, or manual laborer...some part of us says "With yur looks you should be..." Which is part of what the flaw of the American Dream is.

Secondly, in my 60-some years experience, if you're a beautiful but poor male among the rich, that only gets you so far. As far as pool boy, personal trainer, yoga guru, beach bum/fuckboy. Real money still comes with snob-appeal, classism, and a distrust of male beauty.

However, you are 100% right if the scenario is gay. The currency of looks will get you into rich gay circles faster than straight if you are a male.

And I see your point about Shelley Winters' image change. Another matter of perspective. I always saw her as kind of the Karen Black of her time...always playing ladies of low degree and not-too-classy sexuality. For me, A PLACE IN THE SUN represented not only an emphasized seriousness in her performances, but an image-altering de-sexing.

I'd say you've nailed it Ken! 'A Place In The Sun' to me is one of the most brilliantly subversive American films ever made.

ReplyDeleteIn upturning the standard noir sexual narrative (red-blooded all-American boy done in by bad girl's machinations) Stevens knew exactly what he was doing. He challenges our deeper weaknesses...the ones where we may not be too sure at all about who and what we'd kill for. With the assault of beauty, wealth and romance to offset squalid drudgery Mr. Stevens isn't about to let up on our consciences, nor is he going to make anything easy for us and our sympathies.

Hopefully we don't get carried away with ourselves and think it's sad that Taylor and Clift were victims of bad luck because of a bad girl!

Thank you very much, Rick. And there does seem to be something in American culture...tied in with romance, fairy tales, the capitalist worship of the rich...that makes the suffering of the wealthy and beautiful more profound than the suffering of the poor and plain.

DeleteGrowing up I remember how movie magazines and tabloids begged its readers to cry tears of empathy for poor Elizabeth Taylor. Now we see it with the "tragedy" of the Royals and the prince who renounced his crown for love.

Whatever that phenomenon is, A PLACE IN THE SUN did a great job of finding an entertaining way for America to look at itself and its "values." I'll bet if you took a poll of people leaving the theater at the end of a screening of this movie, the vast majority would say that Shelley Winters messed things up for Liz and Monty. But I can be a bit cynical at times.

Thanks you for checking this post out, Rick. Always great to hear you thoughts!