At age 76, multi-Oscar-winning director Steven Spielberg is a full 11 years my senior. But when it comes to our mutual, lifelong love affair/obsession with West Side Story, he's practically my twin.

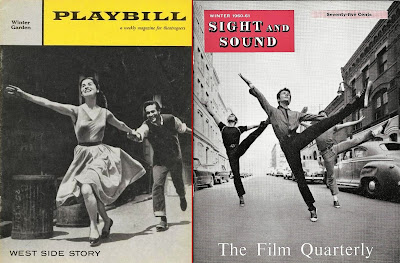

Both of us were introduced to West Side Story at roughly the same impressionable age: Spielberg, when he was 10, via the original 1957 Broadway cast album his father brought home one day (Spielberg dedicates this film to his late father); me, at age 11, by way of the 1967 theatrical re-release of the 1961 Robert Wise/Jerome Robbins movie (detailed in an earlier post). The indelible impression this ingeniously urbanized, musicalized retelling of Shakespeare's Romeo & Juliet made on our young imaginations—book by Arthur Laurents, music by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, original stage production conceived, choreographed, and directed by Jerome Robbins—easily branded West Side Story as the first musical crush for us both.

And while I never got in trouble for singing "Gee, Officer Krupke" at the dinner table like Spielberg, I can certainly attest to having immersed myself in West Side Story's OST Lp with equally matched zeal and fervor. At 11-years-old, I may not have been able to memorize Joyce Kilmer's "Trees," but should anyone have asked, I could have easily recited the lyrics to every song from West Side Story.

|

| 1957 1961 |

Surprisingly, this awareness of a shared reverence for West Side Story did absolutely nothing to mollify the host of misgivings flooding my brain when word came out that Spielberg would be cutting his musical teeth by directing a new screen adaptation of West Side Story. With each new press release cagily sidestepping the dreaded R-word: "remake” in favor of the PR-friendly: “reimaging,”; I could feel the muscles in my neck coiling tighter and tighter. The thought of anyone tinkering with my beloved West Side Story immediately sent me spiraling off into something akin to a film geek's version of bling Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’ “Five Stages of Grief”:

1. Denial – I reminded myself there’d been fruitless talk about remaking West Side Story for decades. Nothing ever came of them, and this time would be no different.

2. Anger – I railed at the Hollywood machine and its remake/franchise addiction. Who the hell asked for a remake of West Side Story? With all the absolutely dreadful musicals in need of remaking, they choose one of the few that got it right? And what about all those great shows that have yet to make it to the screen? Better they should make a film version of Sondheim's Follies or help get Glenn Close that long-deserved Oscar by making of movie of Andrew Lloyd Webber's Sunset Boulevard.

3. Bargaining – Well, I reasoned…if West Side Story HAS to be remade, at least it’ll be by a talented, seasoned old pro like Steven Spielberg. A man who truly loves the material and knows how to tell a story. I kept reminding myself that it could just as easily have been Rob Marshall (Nine), Susan Strohman (The Producers), Tom Hooper (Cats), or Phyllida Lloyd (Mamma Mia!) at the helm. Yikes!

4. Depression – The first leaked photo of the new cast of WSS was underwhelming, to say the least.

.jpg) |

| They say a picture is worth a thousand words. But this one left me with just one: "Uh-oh!" |

Though I've since had to eat my words, my first thought when I saw this cast photo (with its weird cut-and-paste look that turns everyone into floating Colorforms® figures) was that it reminded me of something I'm always happy to forget: an Abercrombie & Fitch ad. The new Maria looked ideal, but the rest of the cast called forth nightmare visions of Newsies (1992) or worse...Richard Attenborough's A Chorus Line (1985).

5. Acceptance – Every single argument of resistance I'd held regarding the wrong-headed inadvisability of what I'd come to regard as "Spielberg's Folly" crumbled into an irrelevant heap at my feet when I got my first glimpse of West Side Story via the premiere of its teaser trailer during the 93rd Academy Awards telecast on Sunday, April 25, 2021. I wasn't ready.

Apparently, all the seized-up muscles in my neck needed to get them to relax was for me to hear that tritone "Jets whistle" again. And all that was necessary to uproot my firmly dug-down heels was to see a mere 90 seconds of montage heralding Spielberg's vision. The trailer gave me instant goosebumps AND waterworks, and suddenly the movie I'd scoffed at for well over a year had become the movie I absolutely had to see.

|

| The Sharks (click image to enlarge) |

Once I stopped resisting the idea of a new West Side Story (i.e., focusing on the innumerable, highly probable ways it could be a disaster) my mind began entertaining the tantalizing possibilities a new adaptation posed. For example, I had not considered how thrilling it might be to hear new, full-scale arrangements of all my favorite West Side Story songs. Auguring particularly well for Spielberg's adaptation was the fact that there was to be none of that desperate "Oscar Bait" business of adding a new song to the score...one composed "Especially for the movie!"

.jpg) |

| The Jets (click image to enlarge) |

West Side Story’s groundbreaking use of dance is such a significant part of its legacy and appeal, I couldn’t wait to see what this version had up its sleeve in terms of tackling the one aspect of the show many fans consider to be sacrosanct; Jerome Robbins’ iconic original choreography. Here again, I was encouraged by Spielberg's instincts. Fearful that he was going to select a flavor-of-the-month choreographer from music videos or pop concerts, my heart leapt when I learned that the film's dances would be created by Justin Peck, Tony Award winner and resident choreographer for the New York City Ballet. Now, you're talking! — ¡Ponle fuego, vamos!

But standing head and shoulders above everything else (eclipsing even my elation at finding out that James Corden hadn't been cast in any role) was my hope for this new West Side Story to offer, at last, a “cringe-free” viewing experience. My love for the classic 1961 version (and its stars, Natalie Wood, Richard Beymer, Rita Moreno, George Chakiris, and Russ Tamblyn) has never waned in all this time. But with each passing year—what with contemporary America rolling out the welcome mat to old-school racism, and the advent of HD Blu-ray rendering all those actors in brownface makeup with a clarity as jarring as it is embarrassing—it has grown more difficult for me to minimize and look beyond the wince-inducing whitewash casting and the stereotyped depiction of its Puerto Rican characters. The chance for a more ethnically-authentic West Side Story was exhilarating in its potential.

.jpg) |

| Rachel Zegler as Maria Vasquez |

.jpg) |

| Anson Elgor as Anton (Tony) Wyzek |

.jpg) |

| Ariana DeBose as Anita Palacio |

.jpg) |

| David Alvarez as Bernardo Vasquez |

.jpg) |

| Mike Faist as Riff Lorton |

|

| Rita Moreno as Valentina |

Although I desperately wanted to see West Side Story when it opened at the El Capitan Theater in Hollywood on Friday, December 10, 2021, a post-Thanksgiving surge in local COVID cases gave pause to my enthusiasm. Therefore, diligently avoiding reviews and spoilers in the interim (easier than you'd think), I finally got to see West Side Story a rather swift-passing four months later when my partner alerted me of it being streamed online in HD for free to AARP members (ka-ching!) as part of its “Movies for Grown-Ups” series. (I think AARP understood the target demographic for this West Side Story better than Spielberg or 20th Century Fox.)

.jpg) |

| Josh Andres Rivera as Chino Martin character change: now a thicc snack |

|

| iris menas as Anybodys character change: now a transmasculine teen and first-rate ass-kicker |

Hats off to any film that can--at my age--reignite that childlike awe I've always held for the way movies can create entire worlds of the believably impossible within a tiny, rectangular frame. Watching West Side Story turned out to be one of the most enlivening movie-watching experiences I’ve had in too long a while. Not to put too much on the shoulders of Spielberg & Co., but who knew that a good, old-fashioned movie musical…magnificently realized…was just the joyous, hopeful glimpse of light I needed to reaffirm my sense of life beginning to emerge from under the dark cloak of Hellscape: America post-2016?

I’ve read pieces characterizing the changes to West Side Story by Tony Kushner (who wrote the screenplays for Spielberg’s Munich-2005, Lincoln-2012, and The Fabelmans-2022) as additions. To me, the work of the Tony and Pulitzer Prize-winning writer feel more like extractions. He extracts the era-defined racial myopia of both the stage and movie adaptations to make the material resonate as truer, not newer.

The pleasure of Spielberg's West Side Story is that I’d almost forgotten what it felt like to see a movie musical that actually feels like a genuine movie. By that, I mean a movie musical that isn't ironic, apologetic, a pastiche, a cartoon, a music video on steroids, or one of those depressingly sterile Glee/High School Musical things that mistake garish hyperactivity for the stuff of dreams. West Side Story, with its unabashed romanticism and playful surrender to the conventions of the genre, feels like an old-fashioned movie musical in the very best sense of the word. Evidence, perhaps, that a…ahem, mature, traditionalist director like Spielberg was just the person for the job.

My favorite thing about the glorious cinematography by Oscar-winner and longtime Spielberg collaborator Janusz Kaminski (Schindler’s List-1993, Saving Private Ryan- 1998, A.I.-2001, Lincoln-2012) is the use of backlight flare and reflective bursts of light and color to create the glamour of dreamy romance or the flashpoint tension of violence.

As much as I respect his talent and have enjoyed several of his movies (Jaws, The Color Purple), Steven Spielberg has never been one of my favorite directors (I compiled a list once, and he doesn’t even make the top 30). Part of this is due to how often he works in genres that never much interested me (action, adventure, war movies, historical dramas). But I also find in his films and directing style a tendency to lapse into mawkish sentimentality or boyish whimsy that in many instances feels misplaced, or contributes to undermining moments of genuine emotion.

But personal tastes aside, I don’t think anyone who knows anything about filmmaking would argue that Spielberg is not a gifted visual storyteller, skilled craftsman, and well-versed in the vocabulary of cinema. The marvelous thing revealed in seeing Spielberg apply his particular brand of “Great Entertainer” genius to a musical, is that the dominant traits of the genre: exuberance, nostalgia, romanticism, dreamy fantasy, broad strokes characterizations, oversized emotions, amplified sentiment…play specifically to Spielberg’s strengths, flatter his flaws, and turn even his most irksome vices into virtues.

|

| Ilda Mason as Luz / Ana Isabelle as Rosalia |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

What ultimately cooled my “How dare they tamper with a classic!” indignation over West Side Story was the degree to which every square inch of every frame stood testament to Spielberg's evident care and affection for the material. His palpable desire to do right by the story, music, and dances gives the film an irresistible exuberance that imbues the now 65-year-old musical with an urgency and freshness I honestly hadn't thought possible. Even as I think about it now, I'm so impressed by the way Spielberg’s West Side Story manages to be respectfully faithful to the theatrical production, honor the film version, yet still leave its mark as a boldly distinctive and personal adaptation.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

For a movie musical to really get to me, there's usually a sequence or image that captures my imagination and etches itself in my mind as emblematic of the moment my heart was lost. Like a dream portal…it’s not anything I consciously select, but rather, some kind of internal Polaroid snapshot taken during that elusive and spontaneous “goosebump moment.” In Ken Russell's The Boy Friend, it was when two dancers became Art Deco figurines on a giant gramophone. In Cabaret it was Liza Minnelli draped like a Dali painting over the back of a chair singing "Mein Herr." And in Jesus Christ Superstar it was when Judas emerges from the catacombs of an ancient arena in a Vegas-fringed bodysuit, flanked by a trio of angels with glowing white afros.

My West Side Story goosebump moment, which has already taken root in my mind as the apex instant of the entire film, is that phenomenal low-angle tracking shot of Anita and a squad of women racing down the middle of the street...full throttle in heels, capris, and twirly skirts a-flipping…in the “America” number. John Ford would understand why this shot is so effective ("When the horizon is at the top, it's interesting. When it's at the bottom, it's interesting. When it's in the middle it's boring as shit!"), but add the combination of music, movement, and jubilant playfulness of the dancers, and you've got a scene that made me gasp as my heart hit the ceiling.

I love that Rita Moreno, 1961 West Side Story's Oscar-winning Anita, is a co-producer on this film and appears in a substantial supporting role created for the film. She's wonderful as you'd expect, and if she didn't get nominated for an Oscar again (she didn't) it wasn't for lack of trying. Her rendition of "Somewhere" is a heartbreaker, and Spielberg practically crafts her role as a series of ready-made Oscar preview clips. All the odds seemed in her favor, but perhaps Natalie Wood was looking down and exacted a little Awards Season karma.

The Golden Age movie musicals I watched on TV as a kid (original vehicles designed to showcase the talents of a particular star) conditioned me not to expect too much in the way of acting from musicals. In my teens, when the economic demands of adapting Broadway hits for the screen necessitated the casting of bankable names, films like Camelot, Paint Your Wagon, and Man of La Mancha all seemed to come with mutually-exclusive ultimatums: “Do you want movie stars who can actually act, or do you want song & dance talent with the screen charisma of Spam? Take your pick, ‘cause you can't have both.”

|

| Everyone shines in West Side Story (hands down the best-acted WSS I've ever seen), but Ariana DeBose (Oscar winner), Mike Faist, & David Alvarez are particularly effective in their roles. |

So, I’ve nothing but admiration for Spielberg using his industry clout (the most financially successful director of all time) and fame (he, in essence, is the film’s bankable star)’s the film’s sole bankable name) to make West Side Story the right way: with an extraordinary ensemble cast of young Broadway-trained. (And hallelujah! No one from the world of pop music!)

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Understandably, many will still find West Side Story inherently problematic no matter how many issues are addressed, but personally, I'm overjoyed that Steven Spielberg made a West Side Story I can embrace fully, rather than love at arm's-length. And now, a few parting shots in appreciative recognition of Steven Spielberg, the visual storyteller.

Prologue / Jet Song

Something's Coming

One Hand, One Heart

I Feel Pretty

As best I could, I’ve tried to keep comparisons between the two West Side Story films to a minimum. The reason why can be found in Stephen Sondheim’s 2010 memoir Finishing the Hat. In it, he relates an anecdote about nervously inviting Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman to see his 1973 Broadway musical A Little Night Music, which Sondheim & Hugh Wheeler had adapted from Bergman’s 1955 film Smiles of a Summer Night.

At the end of the show, Sondheim was quick to apologize to the filmmaker for the liberties taken, whereupon Bergman calmed his fears with a perceptive observation: “No, no, Mr. Sondheim, I enjoyed the evening very much. Your piece has nothing to do with my movie, it merely has the same story.”

That's how I feel about West Side Story 1961 and 2021. The world can accommodate both magnificent musicals. One doesn't have to replace or cancel out the other. And as I have fallen in love with each, there's no need for me to have to choose between them. They're both superb, entirely different movies. They merely share the same story.

BONUS MATERIAL

Not His First Time at the Rodeo

West Side Story may be Steven Spielberg's first full-scale musical, but clearly, the genre has always fascinated him. Musical sequences appear in several of his films (1941, The Color Purple). 1991's Hook was actually conceived and partially shot as a musical (songs by John Williams & Leslie Bricusse). And sometime in the early '80s, a musical titled Reel to Reel was planned but scrapped.

Controversially, Spielberg's Indiana Jones & the Temple of Doom (1984) credits sequence is an elaborate production number of Cole Porter's "Anything Goes" choreographed by Danny Daniels (Pennies from Heaven - 1981).

|

| Kate Capshaw sings to her future husband while modeling what appear to be sequined gardening gloves in Indiana Jones & the Temple of Doom |

Hi Ken,

ReplyDeleteI haven't seen the new version of West Side Story yet, but even so, I fully understand the mixed feelings that this film produces in you.

Cheers,

Juan

Hi Juan - Oh, I hope you will see this version of “West Side Story” soon. Hopefully on a big screen. It flopped badly here, but since virtually 90% of the movies I write about were flops upon release, I take it as a sign that I haven’t lost my touch!

DeleteI really love Spielberg’s film, any initial mixed feelings it once produced in me were eradicated after my 3rd or 4th viewing (Although I must have rewatched the "America" and "Dance at the Gym" sequences 100 times by now). In any event, West Side Story won me over by seduction, pure and simple.

Thanks for reading this post and responding so soon. I always enjoy hearing from you. Take care, and should there come when you do see this version, please let me know if you write about it on your wonderful film blog. Cheers, Juan!

I've been waiting for your review before watching this! I felt, as you did, that it might be kinda lame when compared to the original. In addition, I was also a little wary of it being directed by Spielberg. He's an excellent director but can sometimes use his expertise to generate emotional experiences on the screen that are not entirely earned (though I think you'd be hard pressed to make Westside Story MORE emotional than it already it is). I'm pleased to hear you found it a good film. I'll watch it now!

ReplyDeleteHi Ron - Thanks so much for commenting! Yes, sometimes I find my distinctly personal passion for movies can lead to a kind of aesthetic calcification. I know my tastes so well it's common for me to dig in my heels resisting movies I’m all too certain I won't enjoy. But nobody loves a reversal more than I do, and I’m always so overjoyed when I’m taken by surprise and proven wrong.

DeleteWhen I sat down to watch Spielberg's West Side Story, my only hope was that he hadn’t fucked it up. I hadn’t counted on falling in love with it and it becoming a new favorite movie musical.

I'm glad that my essay provided the nudge you needed to take a chance on seeing West Side Story. When you settle in to watch it, I hope the words of this essay are forgotten and that you view WSS through your own prism of discovery. Happy watching! And, as always, thank you for reading my posts.

You should watch the Showtime series "American Rust." David Alvarez will break your heart.

ReplyDeleteHi, Rick - I don't get Showtime, so this is the first I'm hearing of this show. I Googled it and it sounds fascinating. And I can well believe Alvarez gives a performance of note. Thanks for the recommendation and for reading this post!

DeleteNice appreciation. Makes me want to see it again. It was only the second theatrical film I saw during the pandemic (after "The Last Duel"). Both films were very good, and both screenings were mostly empty amid b.o. disappointment. So sad. I appreciated the somewhat more realistic take, except for the scene where the kids trash the police station while singing "Gee, Officer Krupke." One thing to taunt a couple of cops on your own turf. Quite another to take over the precinct! Even in a musical.

ReplyDeleteAs an admirer of Spielberg and an adoring fan of John Williams, I suppose I have a different orientation from you coming into WSS. Williams, of course, is Spielberg's principal co-conspirator in the use of music to enhance emotional response. As music is the very core of WSS, it seems odd that you respond differently to its effect here. Perhaps you allow expression in musicals that you reject in other kinds of cinema?

Hi John – Even with an almost empty theater, I so envy you for having experienced Spielberg’s “West Side Story” on the big screen. Had I considered the likelihood and probability that seeing WSS at a theater could have been a semi-private screening opportunity, I would have lept at the chance.

DeleteI, too, liked the grittier, more realistic look and feel the film is given. I have yet to get around to posting the captions I've written to accompany the concluding series of screencaps in this essay. But when I do, my commentary regarding "Gee, Officer Krupke" reflects a somewhat similar dissatisfaction with the staging of that number. With an eye cast to perhaps what is also subtly canny about its staging---meaning that I’m not at all sure we’re not supposed to be put off by the whole “taking over the precinct” thing. Especially if we contemplate what would have happened to any of The Sharks had they done the same. As non-whites, it’s unimaginable that they would have been allowed to simply run out the door. Even in a musical. Perhaps Spielberg and Kushner knew exactly what they wanted to say and convey with that scene.

And as for the gorgeous music, I don’t think there’s anything at all odd about my response to the use of music as emotional enhancement in West Side Story vs. its use in other Spielberg films. Chiefly because I adhere to the Stephen Sondheim principle that there is such a thing as “reality” and then there is “musical reality” …and in the latter, I welcome more blatant displays of sentimentality and overt emotionalism than I’d ever have patience for in a film rooted in real-life.

Musical reality (where one accepts characters falling madly in love in minutes, choreographed dance and song to burst out of ordinary circumstances, and all manner of almost operatic emotionalism to be on display) not only allows for musical overstatement, but in some instances demands it. In musicals, I don’t mind having emotions underscored and underlined by song and dance.

But in other movie genres…those more reality-based…I tend to like to discover my feelings about what I’m watching on my own. Sometimes it can be at odds with a film’s intent, but as part of my personal relationship with a movie, it’s what I enjoy. The individual process of discovery and learning…both about the film and myself.

What I’m less fond of is when a movie’s soundtrack tells me how I’m supposed to react during a scene, or ratchets up the emotion of a scene in ways that can feel unearned or inauthentic. Worse is when it feels manipulative…like the director and composer “playing” the audience and eliciting emotions from them that have all to do with “handing” them an experience the artists are perhaps unsure the audience will arrive at on their own.

So, yes, you’re right. I do allow for an emotional expression in musicals demonstrative, oversized, sentimental, even manipulative) that I most definitely reject in other kinds of cinema. Not a steadfast rule (the shamelessly sentimental music of Henry Mancini in “Two for the Road” and “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” strikes me as sublimely evocative) but certainly a distinction I’m willing to make for discussion.

Thank you so much for reading this post. I appreciate your taking the time to comment, for I enjoyed the thoughtful observations and the sharing of your WSS experience. Cheers!

I recall that Pauline Kael disdained WSS, citing other people's praise for "a musical for people who don't like musicals." They were likely responding to the movie's "seriousness" and social criticism. Kael professed to love movie musicals and dislike this one, perhaps for what Andrew Sarris would have called "strained seriousness." I forget her actual complaint against the 1961 film.

ReplyDeleteAny way you slice it, WSS is different. The noun "musical," both stage and screen, almost invariably means musical comedy. WSS is inescapably a tragedy. Tragic stories are more commonly represented in opera, though opera readily embraces comedy as well. Is WSS really so very different -- even unique? Your affection for Hollywood musicals suggests that it fits right into the tradition. Care to elaborate on the similarities and differences?

Hi John - I went to Kael’s book “For Keeps” to revisit her review of WEST SIDE STORY and you’re remembering it pretty well. She didn’t care for what she saw as the film’s ham-fisted seriousness of purpose, nor what she interpreted as its exhaustive attempts at greatness. Referring to Natalie Wood as a “machine-tooled” love-interest and the entire enterprise as “frenzied hokum” as unoriginal as SOUTH PACIFIC or those Busby Berkeley movies of the ‘30s.

DeleteIt's a fabulous read, for Kael is nothing if not a thoughtful and articulate defender of her sometimes wrong-headed points of view. In this instance, she makes a valid point from her perspective (in that WEST SIDE STORY doesn’t fit her particular definition of art), but her point of view feels myopic.

While nothing that WEST SIDE STORY claims for itself as innovation is “new” in and of itself, I think its distinction lies in it all coming together in one theatrical piece that…independent of what she believes audiences are used to…challenges what we’ve been accustomed to expect in musicals.

As you note, musicals and comedy are so linked in our minds that a musical with serious themes are rare. It was also common in movie musicals for the ensemble dancing to be handled by a nameless, faceless chorus of background or ensemble dancers. Usually to no greater purpose than to dazzle and entertain the audience. When ballet was introduced in movie musicals (OKLAHOMA, AN AMERICAN IN PARIS) it was usually classical and disembodied as a dream sequence or fantasy.

If nothing else, WEST SIDE STORY thrust dance and song into the forefront as legitimate forms of expressing more than just love and joy.

Also, I don’t think it can be understated how seldom teenagers (poor ones at that) were the subject of a musical (heretofore represented in musicals largely by Garland & Rooney putting on a show in the barn).

I think Kael conveniently ignores that prior to WEST SIDE STORY “serious” meant opera or ballet. WWS was a pop opera ballet. It didn’t invent any of those elements, but it put them all together like no musical I can think of had before. And in service of a topic (taking youth culture seriously) that would explode and take over the film industry in a few short years, but in 1961 was largely the provinces of drive ins and low-budget rock and roll musicals.

Thanks, John, for an interesting question and talking point!