"The art of film can only really exist through a highly organized betrayal of reality."

François Truffaut

For reasons obvious, the years 2020 and 2021 are largely a blur to me. The pandemic and subsequent lockdown of 2020 turned time into a literal ontological abstraction; with yesterdays feeling as remote and irretrievable as dreams, tomorrows never actually seeming to arrive at all. Only the tail-end of 2021 stands out in my mind. And that's chiefly because I associate it with those snail-pace early days of life in Los Angeles stumbling towards a return to something resembling "normalcy." And not a minute too soon.

For the close of 2021 is also burned into my mind as the days when the American populace—vacillating between being independently suicidal or societally homicidal over having to endure even one second more of inconvenience—seemed hell-bent on making real the allegorical nightmares of Goldman's Lord of the Flies (1963) and Buñuel's The Exterminating Angel (1962).

|

I was so hyped to see this movie; every time I saw a billboard or poster I, practically gasped |

Happily, I also associate the waning days of 2021 with the off-the-charts excitement I felt about the movies slated for holiday release (Nov/Dec). A roster of titles that featured four -count 'em, FOUR!- movies I anticipated with the eagerness of a kid on Christmas Eve. A rarity of sensation that had me remembering how, when I was young, it felt like every month yielded at least a minimum of two or three movies I convinced myself I couldn't live without. Now, in advanced adulthood and during this, Hollywood's Theme Park Ride era of moviemaking (thank you, Mr. Scorsese), I feel fortunate if a calendar year yields even one movie I can get worked up about.

To look forward to something is to foresee a tomorrow. So, at the time, with a new year on the horizon and the world emerging from beneath a devastatingly dark cloud, it was all too easy to take my enthusiasm for this uncommonly rich cinema bounty as a glimmer of post-election hope and reminder that the arts endure.

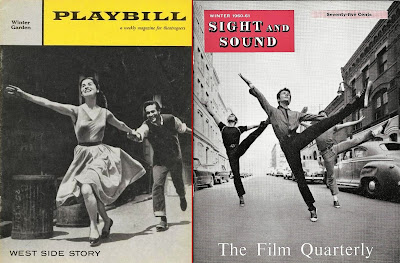

As badly as I wanted to see these films, only West Side Story had me seriously considering leapfrogging over the recent spikes in COVID outbreaks and seeing it in a theater. Ultimately, cooler heads prevailed (one, actually, my partner's) and I kept my ass at home. But thanks to the swift turnaround from theatrical release to streaming, postponing my cinema gratification to early 2022 proved hardly the hardship I'd imagined it would be.

Indeed, the decision to wait only served to feed my already keen excitement. Plus, streaming these films from the comfort of home brought with it the bonus of being able to savor each of these outstanding movies multiple times at my leisure. A perk I'm afraid I indulged to a fault. Particularly as pertaining to The Tragedy of Macbeth, which I rapturously watched five times.

|

| Denzel Washington as Macbeth |

|

| Frances McDormand as Lady Macbeth |

|

| Brendan Gleeson as King Duncan |

|

| Bertie Carvel as Banquo |

.png) |

| Corey Hawkins as Macduff |

.png) |

| Alex Hassell as Ross |

But it's never been a mystery to me why Macbeth stands out from the pack. Classical in structure and (to my way of thinking) often needlessly formal in presentation, Macbeth, as the stuff of movies, is right up my alley in being precisely the kind of dagger-sharp evisceration of the dark side of humanity that characterize a great many of my favorite films. It's a theme I tend to gravitate to and for which (as this blog has revealed to me) I clearly have a decided preference.

Indeed, for me, one of the most mesmerizing things about this, director Joel Coen’s "Dreamscape meets Theater-of-the-Mind" conceptualization of The Tragedy of Macbeth is the degree to which it evokes the very essence of what my sweetheart might label as "Typical Ken Movies":

|

| Even the Macbeths wouldn't mess with this duo |

I'm crazy about Martin Scorsese. Particularly the operatic scope he brings to movies full of psychological and criminal intrigues like Raging Bull (1980), Casino (1995), and The Irishman (2019). Like The Tragedy of Macbeth, many of Scorsese's films are about violent people with Goliath-sized dreams who meet tragic ends due to their inability to get out of the way of their own inherently Lilliputian natures.

|

| Sly Vince Edwards (and his eyelashes) & scheming Marie Windsor in The Killing |

A favorite subgenre of mine is the thriller where a meticulously planned "foolproof" crime goes stupendously off the rails due to weak wills and flaws of character. Lord and Lady Macbeth's grandiose plans are felled by picayune things like jealousy, greed, guilt, and fear. Collapse-points echoed in best-laid-plans favorites like Séance on a Wet Afternoon (1964), A Simple Plan (1998), Before The Devil Knows You're Dead (2007), and Stanley Kubrick's The Killing (1956).

.png) |

| "I say 'we,' Mr. McCabe because you think small." - McCabe & Mrs. Miller |

Movies of the '70s challenged cinema's masculinity myth (and its unwaveringly sure heroes) by giving us dimensional, vulnerable males who experienced self-doubt and were not always dispositionally up to the tasks they set for themselves. A characteristic the vacillating murderer Macbeth shares with the antiheroes of Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation (1974) and Robert Altman's McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971).

|

| "When you durst do it, then you were a man!" - The Tragedy of Macbeth |

Where my partner and I truly part ways in our taste in films is my weakness for movies in which a certain emotional brutalism is used to train a spotlight on aspects of the human condition polite society usually prefers to keep relegated to the shadows. For me, Mike Nichols is a master of this: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966), Carnal Knowledge (1971), and Closer (2004). Where Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth won me over is that it feels wholly uninterested in the violence of swordplay and battle, but, via the extraordinary performances given by the entire cast, goes in really hard when it comes to the emotional and psychological violence the characters inflict upon one another.

|

| Macbeth 1971: For Those Who Think Young "All youth are reckless beyond words." - Hesiod Jon Finch (28) & Francesca Annis (25) in Roman Polanski's Macbeth |

For the longest time, Roman Polanski's sprawling and horrifically naturalistic film held solitary sway as my preferred screen adaptation of Macbeth. But Joel Coen's extravagantly stylized The Tragedy of Macbeth (an interpretation so utterly different in every aspect, no rational comparison between the two can be made) has joined it in an equal-esteem partnership. Two entirely different experiences. Two magnificently realized artistic visions.

.png) |

| Macbeth 2021: No Country for Old Men Frances McDormand (63) & Denzel Washington (66) |

In 1971, Polanski's Macbeth collaborator Kenneth Tynan famously remarked that the idea of a Lord and Lady Macbeth in their 60s was "nonsense" because "It's too late for them to be ambitious." What an absurd statement! As anyone familiar with American politics will tell you, folks over 60 are dangerous as fuck.

|

| Kathryn Hunter as The Three Witches & The Old Man |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

As a film fan enamored of the emotive movie experience, Shakespeare – associating it as I do with Mr. Koller's English class – tends to present a challenge, as my knee-jerk impulse is to approach it academically.

When I watch a screen adaptation of a Shakespeare play, particularly if I'm unfamiliar with it, my mind feels like it splinters off into three channels. One part focuses on the performances, eager to latch onto something I can psychologically or emotionally identify with in these long-ago-created characters. Another gets absorbed in the period detail and recreation of another time and place (Castles! Crowns! Courts! Capes!). And the third part has me wanting to connect to the language, trying to follow the plot while keeping an appreciative ear open to the rhythms of the words (Blank verse? Prose? Iambic pentameter?). Yet, for all these attempts to engage with the material, in the end, I usually wind up just being overly aware of how effortful it's all been.

I enjoy dissecting and analyzing movies, but AFTER I've seen the film, not WHILE I'm watching it.

|

| To Kiss - To Kill Mirrored framing captures the opposite ends of passion's spectrum |

Because I always overthink everything, my cinema ideal has always been the movie that encourages me to turn off my mind and surrender to the sensory, visceral experience. (That I'm free to pick apart to my heart's content later.) The Tragedy of Macbeth—an aesthetically astonishing interpretation that envisions Macbeth as a noirish, metaphysical thriller —gave me just such an experience.

Joel Coen (in his first solo effort after making 18 films with his brother, Ethan) is staggeringly successful in realizing his expressed desire to make a film of Macbeth that doesn't "hide the play." And indeed, The Tragedy of Macbeth's melding of hyper-cinematic mise-en-scène to an aggressively stylized theatricality creates a world dynamically "untethered to reality." As a more cohesively realized example of what Francis Ford Coppola strove for in One From the Heart, The Tragedy of Macbeth achieves what Truffaut called "the betrayal of reality"… film's canny ability to make use of artifice to reveal truth.

|

| Moses Ingram as Lady Macduff |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

As an adaptation of Macbeth that I feel prioritizes the internal and interpersonal struggles of the characters, the lack of ornamentation in The Tragedy of Macbeth's stark visual style extends to its performances. Words are spoken rather than orated, and as there is none of that "In the Grand Shakespearean Tradition" kind of acting on display (except, provocatively, as a signifier of Macbeth losing his mind), it felt like I was given greater access to the pitiable humanity behind Lord and Lady Macbeth’s desperate ambition.

|

| The use of close-ups in The Tragedy of Macbeth forces a sometimes discomfiting intimacy with the characters. |

Cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel's camera seems to exalt (as I did) in letting light and shadow play across the cast's intelligent eyes and expressive, lived-in faces. To watch a contemporary American film is to be bombarded by so much botox, fillers, and tightly-pulled flesh, discerning the display of emotion becomes a game. The facial wrinkles and furrows on glorious display in The Tragedy of Macbeth have poetry.

|

| The Kid Who Would Be King Banquo and his son Fleance (Lucas Barker) |

There's an exchange in the neo-noir thriller Black Widow (1987) where investigator Debra Winger asks serial widow Theresa Russell why marrying even one wealthy man wasn't enough to make her rich. Russell responds: "Rich is hard. You never really figure you're quite there."

Swap "power" for rich, and you've got Macbeth in a nutshell.

The Tragedy of Macbeth taps into a characteristic I've observed in very ambitious people: the joy of attaining an objective always seems so short-lived because there’s no distinction between greed and growth. There's never any arrival point for satisfaction because "having a lot" still doesn't mean "having the most," so there is always more to get. Inevitably, ambition, when unmoored to the spiritual overseers of morality and ethics, creates an internal void. A void that comes to be bridged by that ruinous, self-serving philosophy of the power-hungry…" the end justifies the means."

|

| " 'Tis the eye of childhood that fears a painted devil." / "Yet, here's a spot." |

Lady Macbeth, scoffing at the aftermath of violence, is later haunted by its phantom. The mirroring of shots in The Tragedy of Macbeth infers that despite the exercising of free will, events follow a predetermined pattern.

.png) |

| Ignoble Denzel Washington is my favorite Denzel Washington. His riveting performance as Macbeth totally overwhelmed me. It's a thing of beauty |

PERFORMANCES

Casting Shakespeare with two top-tier American Oscar winners known for their straightforward, naturalistic acting styles sparked all kinds of "Consider the possibilities!" excitement in me. My curiosity about what qualities Denzel Washington (with his unassailable gravitas) and Frances McDormand (she of the stripped-down emotional bluntness) would bring to The Tragedy of Macbeth was rewarded tenfold.

It plays no small part in my adoration of The Tragedy of Macbeth that Washington and McDormand's riveting, poignant performances single-handedly elevate the emotional stakes of this tale like no other I've seen. This is the first adaptation of Macbeth to give me waterworks. There's no end to the accolades I heap upon every member of this assured, accomplished cast. Standouts are Bertie Cavell's Banquo, with his sad eyes and heroic eyebrows. Moses Ingram's regal Lady Macduff. And then there's that flawless changeling, Kathryn Hunter. But a particular favorite is Alex Hassell as the sly Ross, whose role is amplified here and is costumed in a way that fittingly and amusingly has him resembling a male Morticia Addams.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

A parting shot of appreciation for the absolutely breathtaking beauty of The Tragedy of Macbeth. Exquisite Expressionism in a barren, storybook nightmare.

Cinematography: Bruno Delbonnell - Production design: Stefan Dechant

I'd say that perfectly describes how Joel Coen delivers a traditionally 2 ½ hour Shakespeare work (Polanski's Macbeth runs 2 hours 20 minutes) in a bare-bones 105 minutes.

The paring down of the original text is so judicious I never felt I missed a thing. Indeed, I had to re-read Shakespeare's Macbeth with a copy of Coen's screenplay at my side to even know what was excised.

January 2021: In a world emerging from darkness, The Tragedy of Macbeth made an indelible, enlivening impression on me, for it's sometimes too easy to forget the transcendent power of art. I think it's a genuinely masterful film of astonishing beauty that made real for me, the catharsis of tragedy.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)