Reversal of a Dog

Boomerang is one of my all-time favorite romantic comedies. Time has rendered its already-remarkable cast of Black actors a once-in-a-lifetime assemblage, but the film itself is genuinely hilarious and its premise so irresistible, I’m surprised it hasn't been used before (or perhaps it had, only I've failed to come across it).

A callous, commitment-phobic, career-Casanova named Marcus Graham (dashing ad executive Eddie Murphy, ever on the lookout for perfection) suffers an ironic moment of reckoning when, after finally falling in love, he has the tables turned on him. The woman who sweeps him off his feet is Jacqueline Broyer (the elegant Robin Givens), a confident, flattery-immune executive (his new boss, in fact) possessed of effortless self-assurance and plenty of game of her own. A woman who, when it comes to artfully playing the field and displaying a mastery of the game of love-'em-and-leave-'em, proves in every way to be Marcus' match and “dog” doppelgänger.

A callous, commitment-phobic, career-Casanova named Marcus Graham (dashing ad executive Eddie Murphy, ever on the lookout for perfection) suffers an ironic moment of reckoning when, after finally falling in love, he has the tables turned on him. The woman who sweeps him off his feet is Jacqueline Broyer (the elegant Robin Givens), a confident, flattery-immune executive (his new boss, in fact) possessed of effortless self-assurance and plenty of game of her own. A woman who, when it comes to artfully playing the field and displaying a mastery of the game of love-'em-and-leave-'em, proves in every way to be Marcus' match and “dog” doppelgänger.

|

| Eddie Murphy as Marcus Graham |

|

| Robin Givens as Jacqueline Broyer |

|

| Halle Berry as Angela "Agatha" Lewis |

|

| Grace Jones as Helen Strange (pronounced Strawn-J) |

|

| Eartha Kitt as Lady Eloise |

I was instantly reminded of just why Boomerang’s premise

so intrigued me when, while prepping this essay, my search for a laudatory, non-judgmental,

non-pejorative term for the female equivalent of a Casanova or ladies’ man took

me through Thesaurus Hell and back; there really isn't one. The appeal of the so-called charming womanizer has always been lost on be, yet the pop-cultural

cult of the loveable lothario has left us with countless variations on

admiration-laced labels like Romeo, playboy, and roué. But our

culture’s rigid gender double standards have made no such allowances for women.

The only terms I came across for a woman who enjoys playing the sexual field are words reflecting the male gaze (i.e., seductress, temptress), your common vulgar epithets, or words that suggest they evolved out of fear of female sexuality (vamp, siren). I guess that leaves only the second-hand, non-partisan “playgirl.”

The only terms I came across for a woman who enjoys playing the sexual field are words reflecting the male gaze (i.e., seductress, temptress), your common vulgar epithets, or words that suggest they evolved out of fear of female sexuality (vamp, siren). I guess that leaves only the second-hand, non-partisan “playgirl.”

|

| Marcus, a serial girl-watcher, gets a taste of what it's like from the other side when he becomes the objectified, sexualized subject of Jacqueline's dominant gaze |

I was too young for the golden age of the romantic comedy. The days of Cary Grant and Barbara Stanwyck...back when Hays Code censorship necessitated the emphasis on “romance” and chemistry in lieu of demonstrative expressions of sexual attraction. I did, however, grow up in the ‘60s: the era of The Kinsey Report, the sexual revolution, and the heyday of the noxious "swinging playboy" stereotype (think Pal Joey-era Frank Sinatra and his ring-a-ding-ding Rat Pack). Goodbye, witty romantic comedies, hello, crass sex farce. A tiresome formula that presupposed men and women as combatants in formulaic Battle of the Sexes roundelays that all seemed to be about fuck-anything-that-moves bachelors out to trick superannuated virgins into bed before said conquest could trick them into marriage.

|

| Lela Rochon as Christie, a dog-lover who's also susceptible to dogs of the two-legged variety |

Come the '70s, the chase-the-secretary-around-the-desk ‘60s womanizer was reimagined as the free-love hippie hedonist (The Magic Garden of Stanley Sweetheart -1970) or the self-appointed soldier on the frontlines of the sexual revolution (Shampoo - 1975). In the '80s, man-boys replaced grown men in the rom-com landscape (Skin Deep -1989), every story now a variation on the arrested development Peter Pan being chased by a finger-wagging, killjoy Wendy. Mid-decade it became clear that the traditional sexual politics of the romantic comedy would have to change to accommodate women's more progressive, evolved gender status. Hollywood met the challenge by eliminating women from the equation entirely: hello, the Bromantic Comedy.

Yes, those paying attention at the time recognized that the only real rom-coms being made were male-male romances disguised as buddy pictures: e.g., Eddie Murphy’s 48 Hrs (1982) and Lethal Weapon (1987).

|

| Angela: "She's fantastic! I mean, if I were a guy, I would probably be interested in Jacqueline" |

The Good Girl vs Bad Girl Myth

Gender stereotypes mandate that women must always be perceived to be in competition. Angela and Jacqueline are neither rivals nor embodiments of the "good girl vs. bad girl" trope. (Boomerang ascribes no stronger moral failing to Jacqueline's choices than it's also willing to ascribe to Marcus'.) Like the female friends portrayed by Goldie Hawn and Julie Christie in Shampoo, Angela and Jacqueline's dynamic is simply two friends who are after different things from the same man.

The 1990s represented a boom era in Black Cinema. The start

of the decade saw the release of films like To Sleep With Anger, Boyz

in the Hood, Mo’ Better Blues, New Jack City, and A Rage In Harlem. Films that had me harkening back to the Black Film Explosion of the ‘70s--when,

regardless of content or quality, the press insisted on labeling every single

film with a Black cast “Blaxploitation.” The '90s boom produced a wide array of films, and amongst the youth-centric

comedies and heavy dramas, Boomerang provided some much-needed old-style

sophistication, glamour, romance, and escapism.

|

| Geoffrey Holder as "Nasty" Nelson |

Originally (and clumsily) titled Playboy Falls into Love, Boomerang came along at just the right time for me. I’d

long ago made peace with rom-coms being “all hetero, all the time” (a treaty I’ve

since broken), but such egalitarian magnanimity didn’t extend to rom-coms' “all white couples, all the time” view of love. Black couples in romantic comedies were conspicuous by their

absence. When Boomerang came along, For Love of Ivy (1968) and Claudine

(1974) were the only rom-coms on my favorites list that were about Black

couples. And look at how far back we're talking!

It’s as though Hollywood’s narrow-end-of-the-telescope insistence

on filtering everything through a white narrative lens had reduced the entirety

of Black experience to stories about race-based trauma. I imagined industry green-lighters

found it inconceivable that Black people could laugh, meet cute, fall in love, break

up, reconcile, and live happily ever after.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

I’ve always felt the title Boomerang only half refers

to the karmic reversal Marcus Graham’s love life undergoes in the course of the

film. Boomerang is also a fair description of what lies in store for unsuspecting

rom-com audiences confronted with the well-worn clichés of the genre subverted along lines of gender, race, and class.

I respond to Boomerang as I do the ‘70s comedies of

Mel Brooks—it’s the ensemble contributions of the talented cast that make the

film so funny, rather than any particular performance. (Although I could look

at an edit reel of Grace Jones’ scenes exclusively and be in heaven. She’s that terrific.)

Mel Brooks breathed new life into classic film genres like the western (Blazing Saddles) and the horror film (Young Frankenstein) by infusing them with a contemporary, scatological comic sensibility.

The Black Experience is so rarely depicted in movies that all Boomerang had to do to revitalize the romantic comedy was to de-centralize the white gaze. Suddenly, long-familiar situations, characters, and narrative devices felt fresh because of the simple fact then when you change the storyteller, you change the story. Boomerang presented the Black experience as it's lived by those living it, not by how it's seen and interpreted from the outside. It felt liberating to see Black characters humanized, with all the diverse shades of funny, vulnerable, intelligent, ambitious, sensitive, shallow, sexy, outrageous, glamorous...and yes, raunchy. But in a context lacking in response or reaction to the white gaze.

|

| Bebe Drake and the late John Witherspoon are comedy gold as Mrs. & Mr. Jackson, Gerard's country-ass parents |

In trying to think of other "give him a taste of his own medicine" comedies, all I was able to come up with were two. Some Like It Hot (1959), in which two skirt-chasing musicians wear skirts themselves and learn what it's like to be on the receiving end of lecherous male advances. And Goodbye Charlie (1964) has a womanizer being shot by a jealous husband, only to come back reincarnated as a woman and having to fend off men like much like his former self.

Leaving behind such farcical extremes, Boomerang is essentially a sex comedy of manners that has fun skewering traditional gender roles, double standards, and rom-com conventions.

Now the plot gets thick, Mr. Unplayable’s about to catch the short end of the stick. *

|

| Waiting by the Phone |

|

| Taken for Granted |

|

| Woman on Top |

It’s kinda like a boomerang; what

you put out comes back to ya, it’s the same old thing. *

*song "What Comes Around Goes Around" by Kid Sensation - 1995

PERFORMANCES

To anyone who knows me, it should come as no surprise when I assert that for me, the women are the chief attraction and saving graces of Boomerang...especially Grace Jones. It's also rare to see s many women with significant roles in one film. Best of all, they are all so dynamic, charming, funny, and charismatic, they succeed in smoothing out the rough edges attendant with my mixed feelings about the often problematic Eddie Murphy (who, to his credit, in an almost completely reactive role, is actually quite likable here.)

To have Grace Jones, Robin Givens, Halle Berry, Eartha Kitt, Tisha Campbell, and Lena Rochon all in the same movie is some kind of Essence magazine/Ebony Fashion Fair glam wish come true. They're really the film's most valuable players. So good, in fact, that I found myself wishing the guys would all fade into the background and that Boomerang would morph into a hip update of Valley of the Dolls with Eartha Kitt as Helen Lawson, Halle Berry as Neely, Robin Givens as Anne, and Lena Rochon as Jennifer. Grace Jones could play any role she wanted.

What lingers with me and what makes me understand how Boomerang has

grown into a classic and cult favorite is that it’s a glimmering time capsule of

Black culture, highlighting a vast cross-section of amazing Black artists. As a

film, it’s a little piece of comic brilliance that shows its age in some respects but largely reveals how ahead of the curve it was in defining its point of

view and depicting a side of Black life rarely seen on movie screens. The rare entertainment that succeeds in actually being entertaining, I champion

Boomerang for its humor, its heart, its raunchy outrageousness, and especially for its refreshing vision of romance and Black lives lived in a glossy, stylishly old-fashioned Hollywood landscape.

BONUS MATERIAL

With eight weeks in the #1 spot on the R&B charts, the Boomerang soundtrack was a massive hit, with singles flooding the radio airwaves of 1992. To this day my personal fave track remains Grace Jones' "7 Day Weekend," A song that only appears instrumentally in the movie and for which Jones expressed little fondness in her memoirs, citing minimal creative input.

Boomerang spawned a 2019 spin-off TV series produced by Halle Berry and written by Lena Waithe that ran for two seasons on BET. The show took place in modern-day Atlanta and had the adult daughter of Eddie Murphy & Halle Berry running her own advertising agency while being romantically pursued by the son of Robin Givens' character. The reversal of the premise had Marcus and Angela's daughter as the one afraid of commitment, while Jacqueline's son is the one looking to settle down.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2020

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

On television recently I saw Oscar-winning screen icon Cicely

Tyson relate a story about doing promotion for her 1972 film Sounder and

having a white member of the press tell her that the film (about a Black family

of sharecroppers in 1933 Louisiana) forced him to confront bigotry within

himself because he had a hard time accepting the son in the story (Robert

Hooks) calling his father (Paul Winfield) “Daddy.”

Yes, a Black character displaying basic, unremarkable humanity

was enough to strain credibility for this man. And while I’m certain this story

will leave some people feeling all warm and fuzzy because a Black film led a

white man to recognize his prejudices, Tyson recognized it for what it was; a

sign of the vast chasm existing between the reality of Black life and white culture’s

perception of it. The phenomenon is so common it's been given a name--the Racial Empathy Gap, citing the difficulty white audiences often have in relating to Black characters in films. Cicely Tyson went on to say “That’s when I realized I could not afford

the luxury of being an actress. There were some issues that I wanted to address.

That I would use my career as my platform.”

And indeed, it has been the eternal legacy of Black artists in

film to take up the mantle and use their artistic careers as platforms to

combat Black invisibility and present the world with images of dignity to

counter generations of racist dehumanization. But as author Toni Morrison so eloquently

wrote and spoke about, the constant need to frame Black life in ways

understandable, acceptable, and appeasing to white audiences not only seriously

restricts the free, authentic expression of Black experience, but in the end

only reinforces the false dominance of the white perspective.

Spike Lee's pioneering films broadened the scope of what Black films looked like, paving the way for the Hudlin Brothers' Black business world setting of Boomerang (which in real-life inspired the creation of the Marcus Graham Project - a nonprofit dedicated to inclusion in the fields of advertising and marketing).

|

| Father of the Black Film explosion of the 1970s, legendary filmmaker Melvin Van Peebles appears as a film editor |

One of the things I don’t think Boomerang gets enough

credit for is being a Black film that doesn’t center and prioritize whiteness.

Unapologetically uninterested in the white gaze, Boomerang is set in a Black

corporate world so alien and underrepresented on the screen that it strained credibility

for many white viewers at the time (the only way some could process it at all

was to convince themselves it was a fantasy). Boomerang is Black representation that's funny, funky, sexy, loving, and outrageous enough to be comfortable in its own

skin. It foregoes the traditional crossover concerns of respectability politics, uplift roadmaps, and cultural identification signposts.

|

| Director Reginald Hudlin (l.) and producer Warrington Hudlin appear as a couple of street hustlers soliciting Marcus outside of the Apollo Theater. |

Based on a story idea by Eddie Murphy, Boomerang's screenplay is credited to SNL alumni and longtime Murphy collaborators Barry Blaustein & David Sheffield. In the 2003 book Why We Make Movies:

Black Filmmakers Talk About the Magic of Cinema by George Alexander, producer Warrington Hudlin called the duo: "Two white writers who are on Hollywood welfare rolls who just keep getting money with no talent." Labeling the original screenplay for Boomerang "worthless," Hudlin credits the film's Black perspective as emanating from Murphy's original story and the widely-encouraged improvisational skills of the cast.

It was nothing short of exhilarating for me to see myself

and people I recognized in the film’s casual intersection of buppies & homies;

hip-hop and R &B; urban sophisticates and “country” relatives; women in

charge & sex-positivity feminism; Afrocentrism and Dolemite-level

raunch.

I saw Boomerang on opening day July, 1st,

1992 with a friend of mine (now, ex-friend) who found the film profoundly insulting

because she felt the absence of white characters in the film was an act of intentional

hostility on the part of the filmmakers. Mind you, this was a white friend with

whom I’d watched innumerable classic and contemporary movies with all-white casts with nary a peep out of her. Exposure to just ONE film with a prioritized Black gaze was enough

to send her off the rails.

Boomerang is killingly funny and ranks high on my absolute

favorites chart, but it’s far from being a perfect film. I love how prominently

women feature in the narrative and I’ve not one complaint with how they are

characterized or depicted in the film (but I say that with the awareness that the almost 30-year-old film is the collaborative work of men, and that as a male myself, I am hardly the last word on the subject). But I

personally could do without Eddie Murphy’s incessant need to assert his well-documented—since apologized for—homophobia (Good Lord…the man can’t

even let a Frenchman platonically kiss him on the cheek!), and the scenes between

Marcus and his buddies grow more cringe-worthy with each passing year (they trigger

a lifetime’s memories of having to suffer the toxic masculinity byplay of barbershop talk).

|

| Tisha Campbell as Yvonne |

|

| Chris Rock as corporate gossip, Bony T |

|

| And I Will Give U My Heart |

Halle Berry and Eddie Murphy in a clip from "Boomerang" (1992)

With eight weeks in the #1 spot on the R&B charts, the Boomerang soundtrack was a massive hit, with singles flooding the radio airwaves of 1992. To this day my personal fave track remains Grace Jones' "7 Day Weekend," A song that only appears instrumentally in the movie and for which Jones expressed little fondness in her memoirs, citing minimal creative input.

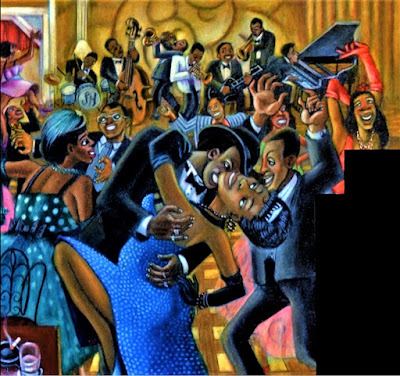

Boomerang introduced me to the magnificent work of African-American artist Romare Bearden (1911-1988). The above piece "Jammin ' at the Savoy" -1980, is featured in the scene where Angela teaches a children's art class.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2020