|

| Warning: Possible spoilers |

All filmmakers start out as film fans, so perhaps it should come as no surprise when—and I stress “when,” not “if”—they find irresistible the urge to pay homage to the movies and directors that inspired them. I don’t mean those directors who’ve built their entire careers on appropriating the style of others (Brian De Palma, Quentin Tarantino); rather, those filmmakers brave/foolhardy enough to adopt imitation as their chosen form of flattery.

Peter Bogdanovich hit critical and boxoffice pay dirt by candidly

riding the cinematic coattails of John Ford and Howard Hawks, respectively, with The Last Picture Show and What’s Up, Doc?. That is, until the leaden

At Long Last Love exposed the director

as having no gift for the light touch required of aping the musical romantic

comedies of the 1930s. Macho Martin Scorsese fared no better with his stab at

the stylized realism of the studio-bound 1940s musical with his shapeless and meandering New York, New York (1977). And Interiors (1978), Woody Allen’s first dramatic

film and beginning of many attempts to clone his idol Ingmar Bergman, was, to many, such

a tin-eared East Coast transmutation of Bergman’s trademark Swedish existential

dread, it's said that at initial screenings some viewers mistook it for a tongue-in-cheek comedy spoof.

|

| Fragile Victim or Femme Fatale? |

When writer/director Robert Benton (Bonnie and Clyde, Kramer vs Kramer, Places in the Heart) tried his hand at updating the 1940s private eye flick, the result was the smart and quirky The Late Show (1977): a small, unpretentious little gem (which flopped tremendously) that made self-referential neo-noir look effortless.

Although I can't deny it is both well-written and watchable, Kramer vs Kramer,

Benton’s wildly popular follow-up to The

Late Show, still strikes me as little more than a pedigreed Lifetime movie (decades before there

was even such a thing as a Lifetime movie),

but it nevertheless proved to be a mainstream cash-cow/award-magnet (a whopping nine

nominations) netting Benton Oscars for Best Director and Best Adapted

Screenplay.

Success on such a grand scale does nothing if not feed expectations,

so when it was announced Benton’s next film was to be a suspense thriller in

the Alfred Hitchcock vein starring such heavy-hitters as Kramer vs. Kramer Oscar-winner Meryl Streep (hot off The French Lieutenant’s Woman), two-time Oscar nominee Roy Scheider

(then most recently for the critically acclaimed All That Jazz), and actual Hitchcock alumnus Jessica Tandy (The Birds);

anticipation was so high it’s likely no film Robert Benton ultimately released could

have lived up to the potential.

As it turns out, the public was spared from having to weigh in on the truth of such speculation when Robert Benton (collaborating with screenwriter David Newman) released Still of the Night. A film that, while unremittingly stylish, well-acted, atmospheric, and one of my I’m-pretty-much-alone-in-this personal favorites (Streep’s take on the Hitchcock blonde is my favorite of all her screen looks)—critics and audiences alike felt it to be a tepid toast to the Master of Suspense which failed to live up to the modest expectations one might harbor for even an episode of Columbo.

As it turns out, the public was spared from having to weigh in on the truth of such speculation when Robert Benton (collaborating with screenwriter David Newman) released Still of the Night. A film that, while unremittingly stylish, well-acted, atmospheric, and one of my I’m-pretty-much-alone-in-this personal favorites (Streep’s take on the Hitchcock blonde is my favorite of all her screen looks)—critics and audiences alike felt it to be a tepid toast to the Master of Suspense which failed to live up to the modest expectations one might harbor for even an episode of Columbo.

|

| Meryl Streep as Brooke Reynolds |

|

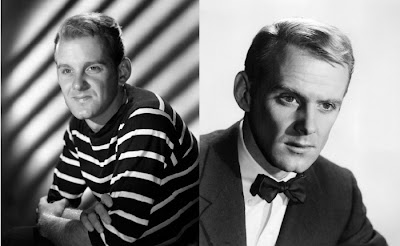

| Roy Scheider as Dr. Sam Rice |

|

| Jessica Tandy as Dr. Grace Rice |

|

| Josef Sommer as George Bynum |

While reeling from the dissolution of his 8-year marriage, emotionally

insulated psychiatrist Sam Rice (Scheider) learns that one of his clients, an auction

house antiquities curator named George Bynum (Sommer), has been brutally murdered.

Bynum, a married, middle-aged narcissist with a Don Juan complex, had come to

Dr. Rice seeking treatment for difficulty sleeping due to a recurring nightmare

somehow related to the enigmatic, much younger woman he was seeing.

Following Bynum’s death, Sam is paid a visit by the very woman in

question, one Brooke Reynolds (Streep), Bynum’s assistant; a fragile, nervousy type with darting eyes, a hesitant manner, and a hairdo in constant

need of fiddling with. Sam, who through his sessions with Bynum has already developed something of a dream-girl fixation on Brooke, finds meeting the

icy blonde in the flesh triggering paradoxical feelings of attraction

and fear within him.

|

| Killer's Kiss? |

Basically an instance of an emotionally immovable object

meeting a cryptic irresistible force, the fact that Sam and Brooke’s attraction

intensifies in direct proportion to both the amount of danger their association

places them in and the degree to which each fears and/or mistrusts the other,

becomes a (grievously underdeveloped) part of their chemistry.

The investigation into Bynum’s murder, deemed to have been committed

by a woman, appears to implicate Brooke, who, at least on the surface, comes across as fragile and damaged as the antiquities she oversees. But is she the vulnerable potential target of

the murderer, or in fact, a cold-blooded serial killer herself? As for Sam, the quintessential ordinary man drawn into extraordinary circumstances, his personal investigation into the crime proves a race against time as he tries to keep himself alive long

enough to discover if his tapes of Bynum’s psychiatric sessions hold the key to

the murderer’s identity.

|

| Joe Grifasi and Homicide Detective Joseph Vitucci |

In fashioning a Hitchcockian romantic thriller set in the cultured world of multimillion-dollar art auction houses and Park Avenue shrinks, it certainly can’t be said of Robert Benton that he faulted on the particulars. For indeed, Still of the Night is an enormously sleek and handsome film, a sophisticated murder mystery fairly drenched in atmosphere and style. Oscar-winning cinematographer Néstor Almendros (Days of Heaven, Sophie’s Choice) channels Fritz Lang and Hitchcock’s trademark close-ups, imbuing Still of the Night’s color-saturated interiors and shadowy nighttime exteriors with a tension and dynamism not always present in Benton’s intermittently dormant script.

But as many filmmakers before and since have learned, capturing

the look and feel of a Hitchcock film is a relative cakewalk when compared to

replicating Hitchcock’s gift for storytelling, his understanding of the

elements of suspense, and his mastery of rhythm and pace through editing.

|

| Sara Botsford as Gail Phillips |

That being said, Still of the Night still ranks among my favorite Hitchcock homage movies, including Donen’s Charade, Chabrol’s The Butcher, De Palma’s Obsession, Truffaut’s The Bride Wore Black, and Zemeckis’ What Lies Beneath.

But as much as I take delight in Still of the Night being a smart and worthy entry in the faux-Hitchcock romantic thriller sweepstakes; I've no problem in confessing that I find the film to be somewhat lacking as a romance, and that Benton's screenplay feels like it's a story meeting or two short when it comes to the payoff ending. Either that or perhaps the victim of last-minute tampering, as Benton had a reputation for

reshoots and rewrites.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

If any of what passes for objective

observations about Still of the Night

ring false in my writing, blame it on the film’s title sequence. Composer John

Kander (sans longtime collaborator Fred Ebb) composed music for Still of the Night described by

biographer James Leve as a “nocturnal waltz theme.” When I sat in the

theater on opening weekend back in 1982 and heard this beautiful melody playing

beneath an elegant credits sequence that featured a full moon floating gently across a midnight sky…I knew instantly, no matter how flawed the forthcoming film

might be, there was no way I was ever going to completely "dislike" Still

of the Night. That opening gave me goosebumps.

To this day I think it’s one of the loveliest, most simply poetic title sequences for a “thriller” I’ve ever seen. So much so that while working on this piece, I made a nuisance of myself by asking my partner to play it for me on

the piano nearly every day.

As for the film itself, I largely regard Still of the Night as a sensual experience. I enjoy its surface pleasures while trying not to focus too much on all the unrealized potential. Unlike many, I actually think Still of the Night is a very effective thriller, providing suspense, mystery, and a few surprises along the way. It has style, tension, strong performances throughout, and a visual distinction that marks it as one of the few films from the '80s to emerge unmarred by hideous fashions and embarrassing hairdos.

|

| John Kander's theme for Still of the Night is intended to "Create an uneasy balance between romance and terror" - James Levee |

As for the film itself, I largely regard Still of the Night as a sensual experience. I enjoy its surface pleasures while trying not to focus too much on all the unrealized potential. Unlike many, I actually think Still of the Night is a very effective thriller, providing suspense, mystery, and a few surprises along the way. It has style, tension, strong performances throughout, and a visual distinction that marks it as one of the few films from the '80s to emerge unmarred by hideous fashions and embarrassing hairdos.

But while I easily find myself stimulated by the particulars of the plot, the ritzy setting, and the overall glossy production values, Still of the Night never engages my heart, rouses my empathy, or involves me in any meaningful, emotional way with the characters. I watch the film at a pleasured remove; happy to be seeing so much talent assembled in the service of an impressive Hitchcock carbon; all the while suppressing my disappointment that the film doesn't ultimately live up to all that is suggested by the collaboration of Benton, Streep, Scheider, Tandy, and Almendros.

Still of the Night succeeds stupendously in capturing the look and

feel of a Hitchcock film, but Benton's screenplay really pulls up short when it comes to characterization. These are less real people than pawns operating in service of a plot. And even there, I'm afraid the ball is dropped a bit, as the complex, marvelously intricate dream sequence that holds so many keys to the central mystery ultimately feels like a letdown once its banal Freudian code is broken.

|

| Opened on Friday, November 19, 1982 at the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood |

PERFORMANCES

Although easy to forget now, one of the major selling points of Still of the Night in 1982 was that it was one of the rare thrillers made for grown-ups. In a marketplace flooded by horror sequels, teen slasher flicks, and sleazy erotic thrillers, Still of the Night's promise of a return to the classic suspense thriller shone like a beacon.

I'd been a Meryl Streep fan since The Seduction of Joe Tynan, so the idea of my favorite actress appearing in one of my favorite film genres was irresistible. In assessing her take on the Hitchcock blonde, here again, it must be said, objectivity is not likely to rear its head. I'm crazy about her in this movie. She's just so marvelous to watch. I just wish her role had been written better.

Roy Scheider, perhaps one of the last of the grown-man actors Hollywood favored before switching to its current taste for superannuated frat boys, is also very good here. But again, his character is underserved by the screenplay, resulting in his chemistry with Streep being more muted than it should be for a film dubbed a romantic thriller.

An actor whose performance has improved over time is Josef Sommer as George Bynum. I was 25 years old when I first saw Still of the Night, and I remember being somewhat grossed back then by this "old fart" who fancied himself a lady's man. Well, remarkably, Sommers was only 47 when he made this film (15 years older than Streep), a good 12 years younger than I am now. Suddenly, he doesn't seem so old, although his character has remained every bit as odious. Sommer may not be playing a very likable individual, but his George Bynum is terrifically realized.

Although easy to forget now, one of the major selling points of Still of the Night in 1982 was that it was one of the rare thrillers made for grown-ups. In a marketplace flooded by horror sequels, teen slasher flicks, and sleazy erotic thrillers, Still of the Night's promise of a return to the classic suspense thriller shone like a beacon.

I'd been a Meryl Streep fan since The Seduction of Joe Tynan, so the idea of my favorite actress appearing in one of my favorite film genres was irresistible. In assessing her take on the Hitchcock blonde, here again, it must be said, objectivity is not likely to rear its head. I'm crazy about her in this movie. She's just so marvelous to watch. I just wish her role had been written better.

Roy Scheider, perhaps one of the last of the grown-man actors Hollywood favored before switching to its current taste for superannuated frat boys, is also very good here. But again, his character is underserved by the screenplay, resulting in his chemistry with Streep being more muted than it should be for a film dubbed a romantic thriller.

An actor whose performance has improved over time is Josef Sommer as George Bynum. I was 25 years old when I first saw Still of the Night, and I remember being somewhat grossed back then by this "old fart" who fancied himself a lady's man. Well, remarkably, Sommers was only 47 when he made this film (15 years older than Streep), a good 12 years younger than I am now. Suddenly, he doesn't seem so old, although his character has remained every bit as odious. Sommer may not be playing a very likable individual, but his George Bynum is terrifically realized.

|

| She's not given much to do, but it's always a pleasure seeing the great Jessica Tandy onscreen |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Perhaps in an effort to stay one step ahead of

Hitchcock-savvy audiences apt to figure out whodunit by the 30-minute mark, Still

of the Night clocks in at a brisk 93 minutes. And while there’s nothing

wrong with a thriller being fast-paced (a wise choice in this instance, given

the relative simplicity of the plot), haste of the sort that forces events to proceed so swiftly—leaving characters and relationships undeveloped—results in a story

that feels rushed.

|

| Brooke gives Sam a Greek Tanagra figurine to replace the desk statue she accidentally broke when she briefly panicked during an earlier visit |

Still of the Night

handles its suspense duties nicely, taking the time necessary to set up pertinent

plot points and having them pay off later, also allowing for the gradual

disclosure of past events (via Bynum’s taped therapy sessions) to inform and

alter our perception of things in the present. Similarly, the film handles the central

murder mystery extremely well, cleverly revealing details in dual “Cherchez la femme”

narratives: one told in flashback by the victim himself (Bynum) as he tries to unravel

the mystery of the woman with whom he’s carrying on an adulterous affair; the other

relayed in the present by Sam, who alternately fears and fears for the woman he

barely knows, yet has fallen in love with. It is on this last point—the romantic

relationship between Brooke and Sam—where Still

of the Night could have most benefited from a few more minutes of running

time.

|

| Innocent Seduction |

|

| Two beautiful enigmas kissing does not a romance make |

Brooke’s allure and mystique are wrapped up in our inability to quite figure her out; thus, her abrupt interest in Sam fuels the film’s suspense. We’re never sure if her attraction to him is authentic or if it is masking a

sinister, ulterior agenda.

But Roy Scheider’s Sam is the character from whose

perspective the film is told, so our being given so little information about

him severely undercuts our engagement in the story. As written, Sam left me

with more questions than Brooke: Is Sam’s remoteness a result of his marriage or the reason the marriage dissolved? Why does a successful psychiatrist live a

life of beige austerity? Beyond her beauty, why exactly is he drawn to Brooke?

They never really even have a normal conversation.

|

| Sam and his psychiatrist mother share a moment of "shop talk" in his sparsely furnished I'm-not-ready-to-be-a-bachelor-again pad |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Filmmakers who venture into the land of Hitchcock homage do

so at their peril, for nothing wrests a viewer out of a narrative faster, nor

tugs at the willing suspension of disbelief more aggressively, than being invited

by the director to engage in a game of “Spot the Hitchcock reference.”

|

| North by Northwest Still of the Night features an auction sequence similar to the one in Hitchcock's film, but where Cary Grant sought the attention of the police, Scheider attempts to divert it |

Unlike those De Palma films where entire sequences are lifted from Hitchcock movies, Still of the Night wisely adheres to “in the style of” homage when it comes to its storytelling. Hitchcock references abound (North by Northwest blonde, Marnie red, Notorious Daddy-issues), but they're subtle and unobtrusive enough for the film to be enjoyed by those not possessing a vast familiarity with the works of the Master of Suspense. Of course, for those who do, Still of the Night offers a wealth of Hitchcock-related dividends, but none so overt as to prove a narrative distraction.

|

| Saboteur/North by Northwest The single-armed, hanging-by-a-thread rescue attempt |

|

| Rear Window Bynum watches Brooke's apartment and spies her undressing for a stranger |

|

| Vertigo A bell tower is the site of a death suspected of being a murder |

|

| Spellbound Brooke and Sam analyze the details of a dream to solve a murder and unlock a dark secret |

|

| The Birds An attacking bird features in the film's biggest "jump" moment |

|

| Psycho The working title for Still of the Night was Stab, so there you have it |

Although they share no scenes together in Still of the Night, Meryl Streep and actor Joe Grifasi are longtime friends, their association going back to their days at the Yale School of Drama in the '70s. Grifasi has appeared with Streep onscreen in The Deer Hunter and Ironweed. Click HERE to see them performing the musical intro to an all-star 2014 charity event.

On a 2012 episode of Andy Cohen's Watch What Happens: Live, Meryl Streep offered up Still of the Night when asked to: Name one bad film that you have made."

Scene from "Still of the Night" - 1982

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 207