Both presuppositions are realized to mind-blowing effect in A

Quiet Place in the Country, an offbeat, exhilarating puzzle of a film that has a lot to say about man, muses, money, and madness. And it does so while oozing irresistible ‘60s-era inscrutability from every artfully-composed frame.

In this sequence, one of several punctuated by imagery alluding to contemporary and classic works of art, a faded beauty in a decaying villa (top r.) assumes a pose reminiscent of Jean-Louis David's 1800 Neoclassical portrait Madame Recamier (top l.). As the figure draws closer, the woman transforms into Rene Magritte's 1951 surreal parody, Perspective: Madame Recamier by David (bottom l.)

A Quiet Place in the Country is a Giallo-hued psychological

thriller about the artist as outsider. A study in the creative alienation that charts one man's slow descent into madness as he wages war with inner demons and suppressed obsessions. In fashioning his subjectively fractured, paranoid vision of the world of art, Elio

Petri takes simultaneous aim at consumerist culture and the moral decay that lies at its core. Specifically, the dehumanizing effects of the market-mandated practice of harnessing and harvesting creativity and artistic expression for the sake of profit.

A film that intriguingly combines diverse elements of style and genre, the tone of A Quiet Place in the Country shifts eerily--and joltingly--from dreamlike to nightmarish in

service of a narrative that’s part murder mystery, part obsessive love story, and part horror film.

|

| Vanessa Redgrave as Flavia |

|

| Franco Nero as Leonardo Ferri |

Franco Nero is Leonardo Ferri, an abstract expressionist artist

living in Milan. An artist whose success is both a source of guilt (he's the one who sets the exorbitant prices charged for his paintings), and resentment (he runs himself ragged filling arbitrary gallery quotas that only feed his belief that success has turned his art into merchandise--just another collectible consumer commodity). Stricken with an acute case of creative stasis and trapped within a kind of existential inertia, he fears that his methods of creation--a spontaneous, gestural, “action painting” technique---are becoming obsolete in the high-volume Pop Art world of mixed media and mechanical reproduction.

A modern artist pitted against modernism, everything about his work has grown too “too” for the contemporary marketplace: his prices too high, his methods too slow, his canvases too large, and his art too impenetrable.

A modern artist pitted against modernism, everything about his work has grown too “too” for the contemporary marketplace: his prices too high, his methods too slow, his canvases too large, and his art too impenetrable.

|

| Normative Dualism The mental and physical in the creative process |

With his two-month creative dry spell threatening to turn into

three, stress and isolation take an ever-increasing toll on Leonardo's mind and psyche. Most provocatively, in serving to escalate his already

conflicted feelings for Flavia (Vanessa Redgrave), his married lover

who also just happens to be his agent.

The cool pragmatist to Leonardo’s exposed-nerve fantasist, Flavia—who

has him on an allowance, keeps tabs on his work output, and is forever

scribbling down figures in ledgers—loves him, but is shrewdly accepting of his paranoid distrust and need

to cast her as the villain in their relationship. Flavia: (catching sight of him eyeing

a weighty object d’art in his apartment): "Darling, Leonardo…you can’t kill me with that, it’s

just a big paper clip.”

The ambiguity of perception figures significantly in how A Quiet Place in the Country builds suspense and consistently keeps the viewer on unsteady ground. Early in the film, Leonardo is depicted as the bound, passive, sex-object exploited both physically and creatively by the materialistic Flavia. The ready assumption is that we're seeing Leonardo's perception of the dynamics of their relationship. Later in the film, this scene is mirrored in a way that casts it in an entirely different light.

Owing at least part of his artist’s block to the challenge

of trying to create meaningful work in the face of society’s capitalism-fed, art-as-consumer-goods

ethos (he’s seen reading Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the

Age of Mechanical Reproduction), Leonardo seizes upon the reasoned notion that the only way to get his inspiration mojo working again is to move away from the distractions of the city to a place of isolation and quiet where he can be at one with his thoughts.

Fate seems to oblige all too readily by placing in his path a remote, deteriorating villa that fairly beckons to him from the road. Although its condition is rundown and locals whisper about it being haunted by the ghost of a beautiful Countess who died there 40 years ago; the villa is nevertheless a secluded, bucolic spot offering Leonardo

everything he’s looking for. And quite a bit of what he'll forever wish he'd never found.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS MOVIE

A Quiet Place in the Country is a sociopolitical, psychosexual haunted

house movie that always feels a hairsbreadth

away from submerging itself in its own late- ‘60s stylization. A thinking-person’s

Giallo that incorporates all the familiar tropes of the genre (murder mystery, amateur

sleuthing, graphic violence, eroticism, red herrings, etc.), its chief

deviation from tradition—and key determiner as to whether or not this film will

be your cup of tea—is its commitment to preserving the twitchy schizophrenic perspective

of its abstract artist protagonist. Something achieved by presenting its rather straightforward

story in as arty, willfully cryptic a manner as it can get away with without having to identify itself as avant-garde experimental

cinema. It’s not that A Quiet Place in the Country doesn’t have a beginning, middle, and end, it’s

just they’re arranged in a different order.

But for me, the style IS the story of A Quiet Place in the

Country, a modern gothic tasking the viewer with determining whether a chain of increasingly bizarre events befalling a brooding hero is rooted in the psychological or the paranormal. As obscure and enigmatic as Petri’s images may be (pretentious...sure, heavy-handed...yes, fascinating...always), they credibly convey Leonardo's mental disintegration and heighten identification with the character. Petri's intimate style also poignantly underscore themes in the film interpreting the creative impulse--the need to express oneself and be understood by others--as an outer-directed primal compulsion compensating for the inner-inaccessibility of the unknowable self.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Given my fondness for the hyper-stylized charms of Gialli, it

surprises me to think just how late to the party I was in getting around to

seeing my first Italian Giallo film as recently as 2016. The film was Lucio Fulci’s extraordinary Lizard in a Woman’s Skin (1971), and it so knocked my socks off that I went from 100% unfamiliarity with the genre to having since added some 40 Giallo titles to my film library.

I’m not sure that I’ve yet reconciled myself to the violence

(making me thankful for that fake-looking, poster-paint-red blood they used back in the

day), but I never cease to be impressed by how accommodating the genre is to such

a broad scope of narrative concepts. There’s room for everything from gumshoes

to ghosts under the Gaillo banner.

Idée Fixe

Flavia, the realist, and ever the consumer, is preoccupied with wealth. Leonardo, a resuscitated sensualist since moving to the country, is fetishistically bewitched by a yonic scrap of clothing once worn by the woman he thinks is haunting the villa.

As an example of the “arthouse horror” style of Giallo, A Quiet Place in the Country is low on sensationalism, surpassingly high on atmospheric mystery, and takes a cue from its title by trading the gaudy colorfulness I usually associate with the genre, for a kind of baroque naturalism. The very effective result is that supernatural terrors take place in the brightness of day, and hallucinations and spectral visions are made all the more disturbing by being indistinguishable from reality.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

A Quiet Place in the Country is genre-faithful as a murder mystery, a Giallo thriller, and a supernatural horror film, but its presentation is perhaps too iconoclast and its appeal too niche for me to recommend it wholeheartedly. Personally, I was absolutely enthralled by the film from the first frame to the last, finding much in what Elio Petri had to say about art and alienation still relevant and echoed in contemporary films like Nocturnal Animals (2016) and Velvet Buzzsaw (2019).

There's a thin membrane separating impulse, instinct, and inspiration. A Quiet Place in the Country suggests the wall distinguishing between passion, obsession, and compulsion is perhaps nonexistent.

|

| Terrified at the prospect of spending the night alone after witnessing a particularly hair-raising display of ghostly pyrotechnics, Leonardo imposes himself upon his maid and her "brother." |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

It’s been my experience that it’s very rare for a really

intriguing horror film or mystery to have a payoff that lives up to its setup.

The more disturbing the journey, the greater the chance the Big Reveal will

prove anticlimactic. Against all odds, A Quiet Place in the Country ranks

as one of those rarities. For me, it was an effectively compelling chiller with

a doozy of a surprise ending worthy and fitting of all the with-it weirdness

that came before it.

By large measure, credit is owed to Oliver Onions’ impeccably-structured

source novel; longtime Gialli cinematographer Luigi Kuveiller (Lizard in a

Woman’s Skin, Antonioni’s L’Avventura, and Andy Warhol’s two 3-D horror

titles, Dracula / Frankenstein); and a rattle-your-bones improvisational

music score by Ennio Morricone and Nuova Consonanza.

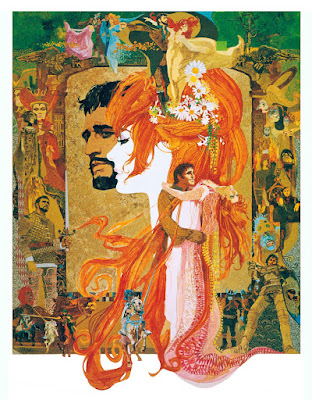

But as a huge fan of the exquisitely elephantine Camelot (1967) I'd be lying if I said that any part of this remarkable film impressed me more than the reteaming of Vanessa Redgrave and Franco Nero... MY Lady Guenevere and Sir Lancelot (the 2nd of some five films they would come to make together). Playing emotionally enigmatic lovers, both actors inhabit their roles with charismatic ease (Nero's the best I've ever seen him), their real-life sensual chemistry breathing life into the film's hyperventilating eroticism.

|

| Autoerotic Leonardo Becomes His Own Sex Object |

But as a huge fan of the exquisitely elephantine Camelot (1967) I'd be lying if I said that any part of this remarkable film impressed me more than the reteaming of Vanessa Redgrave and Franco Nero... MY Lady Guenevere and Sir Lancelot (the 2nd of some five films they would come to make together). Playing emotionally enigmatic lovers, both actors inhabit their roles with charismatic ease (Nero's the best I've ever seen him), their real-life sensual chemistry breathing life into the film's hyperventilating eroticism.

A Quiet Place in the Country is genre-faithful as a murder mystery, a Giallo thriller, and a supernatural horror film, but its presentation is perhaps too iconoclast and its appeal too niche for me to recommend it wholeheartedly. Personally, I was absolutely enthralled by the film from the first frame to the last, finding much in what Elio Petri had to say about art and alienation still relevant and echoed in contemporary films like Nocturnal Animals (2016) and Velvet Buzzsaw (2019).

There's a thin membrane separating impulse, instinct, and inspiration. A Quiet Place in the Country suggests the wall distinguishing between passion, obsession, and compulsion is perhaps nonexistent.

Clip from "A Quiet Place in the Country" (1968)

BONUS MATERIAL: |

| The TV version of The Fair Beckoning One |

That Redgrave and Nero were considered quite the scandalous pair in their day, now seems rather quaint. The two met in 1966 while making Camelot, lived in sin (gasp!), and had a baby out of wedlock before separating in 1971. Shocking stuff, that.

What makes their story the stuff of fairy tales is their reuniting after several decades apart, and getting married in 2006. A story made all the more romantic due to countless interviews given by the never-married Nero over the years claiming he would never marry and that Redgrave had been the love of his life. In 2017 the couple danced together on the Italian TV show Strictly Come Dancing (below).

|

| 1968 2017 |

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2020