Watch. Rinse. Repeat.

I don’t know of any other film in my collection of heavy-rotation

favorites that has undergone as many transformations of perception for me as Shampoo. It seems as though every time I

see it, I’m at a different stage in my life; each new set of life circumstances

yielding an entirely different way of looking at this marvelously smart comedy.

Shampoo has been

described as everything from a socio-political sex farce to a satirical

indictment of American moral decay as embodied by the disaffected Beautiful

People of Los Angeles, circa 1968. Taking place over the course of 24 hectic

hours in the life of a womanizing Beverly Hills hairdresser (Terrence McNally’s

The Ritz mined laughs from the improbability

of a gay garbage man; Towne & Beatty do the same with its

not-as-funny-as-it-thinks-it-is heterosexual hairdresser running gag), Shampoo chronicles the petty crises, joyless

bed-hopping, and self-centered betrayals amongst a particularly shallow sampling of the denizens of The City of Angels—assuming, of course, betrayal is something possible between

individuals incapable of committing to anyone or anything.

The film takes place in and around Election Day 1968, and, fueled by our foreknowledge of what Nixon’s Presidency portended for America with its attendant undermining of the nation’s moral fiber and erosion of political faith; Shampoo attempts—not always persuasively—to draw parallels. The film reflects on the political optimism of the '60s and contrasts it with the narcissistic aimlessness of a small group of characters. Characters who can’t stop looking into mirrors or get their collective heads out of their asses long enough to take notice of anything around them which doesn't impact their lives personally. No one in the film even votes!

|

| Nixon's the One Four people, each with their own agenda. Five if you count the smiling portrait in the background |

The film takes place in and around Election Day 1968, and, fueled by our foreknowledge of what Nixon’s Presidency portended for America with its attendant undermining of the nation’s moral fiber and erosion of political faith; Shampoo attempts—not always persuasively—to draw parallels. The film reflects on the political optimism of the '60s and contrasts it with the narcissistic aimlessness of a small group of characters. Characters who can’t stop looking into mirrors or get their collective heads out of their asses long enough to take notice of anything around them which doesn't impact their lives personally. No one in the film even votes!

|

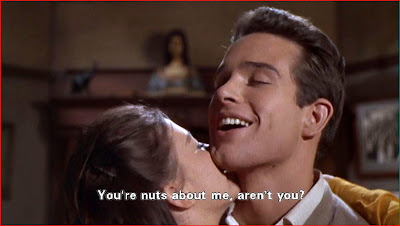

| Warren Beatty as George Roundy |

|

| Julie Christie as Jackie Shawn |

|

| Goldie Hawn as Jill Haynes |

|

| Lee Grant as Felicia Karpf |

|

| Jack Warden as Lester Karpf |

George (Beatty), an aging lothario and preternatural adolescent, may be the most popular hairdresser at the Beverly Hills salon where he

plies his trade, but sensing time passing, feels the pang of wishing he had

done more with his life. George’s ambition is to open a place of his own, but

the not-very-bright beautician routinely undermines his long-term goals by allowing

himself to become distracted by the short-term gratification offered by all the grasping women and easy

sex that got him into the hairdressing business in the first place. Juggling a

girlfriend (Hawn), a former girlfriend (Christie), a client (Grant), that

client’s teenage daughter (Carrie Fisher, making her film debut), all while

trying to negotiate financing for the salon from said client’s cuckolded

husband (Jack Warden); George finds himself in way over his pouffy, Jim

Morrison-tressed head.

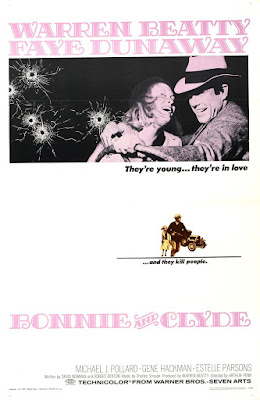

Directed by Hal Ashby (Harold

& Maude), Shampoo is really

the brainchild and creative collaboration of two of Hollywood ’s most legendary tinkerers: Warren

Beatty and screenwriter Robert Towne. Some sources site Shampoo's genesis as having originated with discarded ideas for 1965's What's New, Pussycat? (a film initially to have starred Beatty), while a Julie Christie biography credits her with having brought the 1675 restoration comedy The Country Wife to Beatty's attention, and it serving as the real source material for Shampoo.

Legend also has it that Shampoo—which underwent nearly 8-years of rewrites and countless hours of on-set nitpicking—was inspired as much by Beatty's own exploits as Hollywood’s leading man-slut, as that of the life of late hairdresser-to-the-stars, Jay Sebring (a victim of the Manson family that fateful night in 1969. Beatty was Sebring’s client for a time). Also thrown into the mix: celebrity hairstylist Gene Shacove (who is given a technical consultant credit for Shampoo, but whom I mainly know as a litigant in a 1956 lawsuit filed by TV personally/cult figure, Vampira, claiming he burned her hair off with one of his dryers). Even hairdresser-to-producer Jon Peters (Eyes of Laura Mars) weighed in, claiming the film was inspired by his life.

That so many men actually clamored to be credited with being the inspiration for a character depicted in the film as a selfish, shallow, narcissistic, slow-witted, self-disgusted loser, is perhaps the aptest, ironic commentary on the absolutely stupefying superficiality of the Hollywood/Beverly Hills set.

Legend also has it that Shampoo—which underwent nearly 8-years of rewrites and countless hours of on-set nitpicking—was inspired as much by Beatty's own exploits as Hollywood’s leading man-slut, as that of the life of late hairdresser-to-the-stars, Jay Sebring (a victim of the Manson family that fateful night in 1969. Beatty was Sebring’s client for a time). Also thrown into the mix: celebrity hairstylist Gene Shacove (who is given a technical consultant credit for Shampoo, but whom I mainly know as a litigant in a 1956 lawsuit filed by TV personally/cult figure, Vampira, claiming he burned her hair off with one of his dryers). Even hairdresser-to-producer Jon Peters (Eyes of Laura Mars) weighed in, claiming the film was inspired by his life.

|

| Blow Job |

I saw Shampoo nearly a year after its release (I fell in love with the movie poster and bought it long before I even saw the film), but remember distinctly what a huge, huge hit

it was during its initial release. I mean, lines around the block, rave reviews, lots of word of mouth, and

endless articles hailing/criticizing it for its frank language and (by '70s

standards) outrageous humor. Its popularity spawned many satires (The Carol Burnett Show featured a character named Warren Pretty), porn rip-offs (the subject is a natural), and even spawned an exploitation film titled Black Shampoo, which I've yet to see, but I hear features a chainsaw showdown with the mob(!) Anyhow, Shampoo is

a marvelous film, to be sure, but in hindsight, I think a sizable amount of the

hoopla surrounding it can be attributed to two things:

1) The "The Sandpiper" Factor. In 1965 audiences made a hit out

of that sub-par Taylor/Burton vehicle chiefly because it offered the

voyeuristic thrill of seeing the world’s most famous illicit lovers playing

illicit lovers. The same held true for Shampoo.

In 1975, audiences were willing to pay money to speculate about the similarities

between Shampoo’s skirt-chasing

antihero and Warren Beatty’s reputation as Hollywood's leading ladies’ man. That the

film featured on-and-off girlfriend Julie Christie; former affair, Goldie Hawn

(so alleges ex-husband, Bill Hudson); and future girlfriend, Michelle Phillips,

only further helped to fuel gossip and sell tickets.

2) Pre-Bicentennial jitters. Shampoo was released at the beginning of 1975. Three years after the

Watergate Scandal broke, one year after Nixon’s impeachment, and just three

months before the official end of the Vietnam War. As the flood of “Crisis of

Confidence in America” movies of 1976 proved (Nashville, Taxi Driver, Network, All the President’s Men, etc.) movie audiences were more than

primed for anything reaffirming their suspicion that America’s values were in

serious need of reexamination.

.JPG) |

| Carrie Fisher (making her film debut)as Lorna Karpf In 1975 this line got a HUGE laugh. Her other famous line got a HUGE gasp |

|

| In Shampoo's most talked-about scene, Rosemary's Baby producer William Castle chats up Julie Christie, while to Beatty's left sits character actress, Rose Michtom. Fans of Get Smart will recognize Rose from her 44 appearances on that TV show (one of the executive producers was her nephew). A curious tidbit: she's the daughter of the inventor of the Teddy Bear(!), and even has a website devoted to her Get Smart appearances. |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

Movies about unsympathetic people are not always my thing, but

I do admit to being a sucker for films that address a subtle human truth I've encountered many times in my interactions with people: my dislike of a distasteful person often pales in comparison to the depth of their own self-loathing. There's often a great deal of pain and self-recrimination behind the "have it all" facades of people society has convinced us live "the good life." In sending up the lives of Hollywood's tony set, Shampoo does a great job of making us laugh at the sad fact that there's often not a lot of "there" there.

Shampoo is that it is one of those rare films which showcases the lives of the rich and privileged, yet at the same time is able to convey a sense of hollowness and self-disappointment at the core of each of its characters. And in a comedy yet! It’s a subtle, extremely difficult thing to do (talk to Martin Scorsese about The Wolf of Wall Street), but it gives characters you might otherwise loathe, a sense of humanity. They become individuals whom I can both identify with and understand…if not necessarily like. I think the award-winning screenplay by Towne/Beatty is absolutely brilliant. An early draft of which I read, even more so, as it fleshed out the friendship between Jackie and Jill even more.

Shampoo is that it is one of those rare films which showcases the lives of the rich and privileged, yet at the same time is able to convey a sense of hollowness and self-disappointment at the core of each of its characters. And in a comedy yet! It’s a subtle, extremely difficult thing to do (talk to Martin Scorsese about The Wolf of Wall Street), but it gives characters you might otherwise loathe, a sense of humanity. They become individuals whom I can both identify with and understand…if not necessarily like. I think the award-winning screenplay by Towne/Beatty is absolutely brilliant. An early draft of which I read, even more so, as it fleshed out the friendship between Jackie and Jill even more.

|

| Producer/director Tony Bill plays TV commercial director, Johnny Pope |

PERFORMANCES

OK, I’ll get this out of the way from the top: Julie

Christie is absolutely amazing in this movie (surprise!). Not only does she look positively stunning throughout

(even with that odd hairdo Beatty gives her, which I've never been quite sure was supposed to be

funny or not) but she brings a sad, resigned pragmatism to her rather hard

character. A character not unlike Darling’s

selfish Diana Scott. Whatever one thinks

about her performance, I think everyone can agree that stupendous face of hers is

near-impossible not to get lost in.

|

| As Shampoo's most sympathetic character, from her early scenes as a ditsy blond to the latter ones revealing a clear-eyed, defiant strength, Hawn shows considerable range. |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Shampoo is peppered with celebrity cameos and walk-ons. All adding to the feeling that this isn't a period film taking place in 1968 (in many ways the period detail in Shampoo leaves a lot to be desired) so much as a 1975 tabloid-inspired Warren Beatty roman à clef.

|

| Michelle Phillips |

|

| Susan Blakely |

|

| Andrew Stevens |

|

| Howard Hesseman |

|

| Jaye P. Morgan |

|

| Joan Marshall, aka Jean Arless from William Castle's Homicidal, aka Mrs. Hal Ashby |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

As films go, Shampoo is all about rinse and repeat. It's a new film each time I revisit it.

1975- First time I was a sex-obsessed teenager (and virgin).

Beatty seemed old to me at the time, so I didn’t fully understand how a fully-grown

man could allow his life to unravel around him due to an inability to keep it

in his pants. What did I know?

1983- OK, let’s put it this way; at this stage of my life I “got”

the whole sex thing in Shampoo. Also,

I was living in Los Angeles by this point, so not only had the film’s satirical

jibes at Los Angeles “culture” grown funnier, they became perceptive.

1990- Throughout the '80s and '90s, I worked as a dancer, an

aerobics instructor, and a personal trainer in Los Angeles. If you have even a

tangential familiarity with any of these professions, you’ll understand why, at

this stage, Shampoo started to take on the look of a documentary for me. In fact, I

came to know several George Roundys over the years. Straight men drawn to these largely female-centric professions, amiable, screw-happy, and more than willing to reap the benefits of working all day around women, and being in the sexual-orientation minority where males were concerned. All of

them exhibited behavior so identical to that attributed to the George character

in Shampoo, I gained a renewed respect for the accuracy of Towne and Beatty’s

screenplay.

Today- I’m happily in my late 50s (I'm happy about it, not

ecstatic); nearly 20 years into a committed; loving relationship; thankful and gratified by the journey of growth my life has been and continues to be. When I look at Shampoo now, I watch it with empathy toward its characters I don’t believe

I had when I was younger. Who knew then that so much in the film referenced merely growing up? (Jill's exasperated harangue at George, Jackie being surprised that an old hippie friend is still throwing the same kind of parties).

I think what I now know that I couldn’t have known in

my 20s or 30s, is the profound emptiness of these people’s lives. Never having

been in love before, I didn’t know what I was missing. Now I understand how wonderful

a thing it is to be that close to someone—to trust someone that much—to be able to share a life; and how terrifying and disappointing life can feel without it.

Especially when one faces the realization—at middle age, yet—that

the very life choices one made so casually in one’s youth (the lack of introspection, the

inattention to character, kindness, or concern for others) have consequences that can render one incapable

of ever attaining these things.

|

| It's too late... Jackie checks to makes sure her future is still secure with Lester as George confesses his vulnerability |

Shampoo is still amusing to me, but its comedy has more of a wistful quality about it these days. A wistfulness born of the characters' regret over time wasted, and the bitterness that comes of reaping the rotted fruit of (as Socrates wrote) "the unexamined life." Shampoo to me is a film that mourns the loss of '60s optimism (the use of The Beach Boy song, Wouldn’t it be Nice? is truly inspired) and stares out at us through a smoggy sky looking to a future that, at least in 1975, must have seemed pretty hopeless.

BONUS MATERIAL

Every hetero hairdresser in Hollywood sought to be credited with being the inspiration for Shampoo's not-entirely-sympathetic George Roundy. Among the most vocal was '70s hairdresser to the stars and movie-producer-to-be Jon Peters.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2014

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)