I remember having had a dismissive reaction

to Let’s Scare Jessica to Death when ads for the low-budget feature began appearing in the newspaper during the summer of 1971. I was never much into horror in those days, my tendency to take them too seriously spoiling all the intended fun of being scared, so the somewhat jocular tone of the title only cemented my resolve to leave the film alone.

My older sister, a horror enthusiast and the only one of us

kids to make it through the broadcast TV premiere of Psycho in 1967, went to see “Jessica”

and had raved about it, but I couldn’t be swayed. Jump ahead to the late-‘70s.

Films like Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976) and John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) had turned me into, if not exactly a bonafide horror hound, then certainly an individual more appreciative of the genre and its power to do more than simply offer up the odd shiver and gasp. By this time I'd also come to be aware of actress Zohra Lampert via her appealing but brief appearance as Warren Beatty's make-do wife in Elia Kazan's Splendor in the Grass. A unique and talented two-time Tony Award nominee with an Actor’s Studio pedigree, Lampert was so unlike the type of actress one usually finds in horror movies, I was intrigued.

Happily, by this time Let’s Scare Jessica to Death had become something of a staple on late-night TV and local Creature Features-style programs.

Films like Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976) and John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) had turned me into, if not exactly a bonafide horror hound, then certainly an individual more appreciative of the genre and its power to do more than simply offer up the odd shiver and gasp. By this time I'd also come to be aware of actress Zohra Lampert via her appealing but brief appearance as Warren Beatty's make-do wife in Elia Kazan's Splendor in the Grass. A unique and talented two-time Tony Award nominee with an Actor’s Studio pedigree, Lampert was so unlike the type of actress one usually finds in horror movies, I was intrigued.

Happily, by this time Let’s Scare Jessica to Death had become something of a staple on late-night TV and local Creature Features-style programs.

Let's Scare Jessica to Death's eventual status as a cult film grew out of these wee-small-hours-of-the-morning broadcasts, but as far as I was concerned, if there was ever a film one should not

be introduced to via the accompaniment of frequent commercial interruptions; intrusive,

mood-killing host segments; and the murky dimness of pre-HD TV, it’s Let’s Scare Jessica

to Death. Already dealt a death blow with a grossly misleading shocker title that sets the viewer up for deathly scares that never materialize, the addition of commercials and comedy bumpers completely blows Let’s Scare Jessica to Death's deliberate pacing and low-simmer disquietude straight to hell. The first time I saw it, Let's Scare Jessica to Death felt like the slowest, darkest (as in underlit), least-eventful horror film I’d ever seen. I only made it through about 30 minutes before I grew impatient with waiting for something to happen. Nearly 30 years would pass before we’d meet again and I'd come to realize that when it comes to certain films, patience is definitely a virtue.

|

| Zohra Lampert as Jessica |

|

| Barton Heyman as Duncan |

|

| Mariclare Costello as Emily |

|

| Kevin O'Connor as Woody |

Following the death of her father, New Yorker Jessica (who appears to be a folk artist of some sort) suffers a nervous

breakdown and is institutionalized for six months. Upon her release, Jessica's husband Duncan quits his job as cellist for the New York Philharmonic, and in the interest of starting a new life, sinks all of their savings into the purchase of a 19th Century farmhouse and apple orchard in a remote rural section of Connecticut. With the help of their family friend, Woody, Jessica and Duncan embark on their pilgrimage, Jessica (whom it’s alluded has had no say or hand in the selection of the house) expending considerable energy in trying to convince them...and herself...that all is “fine” and that the ever-escalating doubts she harbors about the state of her sanity are baseless. But they aren't.

Almost immediately upon arrival, Jessica begins hearing voices and experiencing what she believes to be hallucinations, but she's afraid to voice her concerns. Not an easy task, given that their new home looks like it was once owned by The Munsters and that its history is attached to a macabre local vampire legend. Adding further fuel to Jessica's mental health fires, the nearby town is totally devoid of women and populated exclusively by bandaged, oddly antagonistic, old men.

Almost immediately upon arrival, Jessica begins hearing voices and experiencing what she believes to be hallucinations, but she's afraid to voice her concerns. Not an easy task, given that their new home looks like it was once owned by The Munsters and that its history is attached to a macabre local vampire legend. Adding further fuel to Jessica's mental health fires, the nearby town is totally devoid of women and populated exclusively by bandaged, oddly antagonistic, old men.

|

| Gretchen Corbett as The Girl in White |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

It was 2010 before I ever sat down and watched Let’s Scare Jessica to Death in its

entirety. By which time the middling state of contemporary

horror films had given me an appreciation of the very things I once hadn't cared for in this movie back when

I first saw it in 1978. In fact, its depiction of post-60s hippiedom is so evocative that I really wish I had seen it during its initial 1971 release. It perfectly captures the feel of what I recall about ‘70s-era Berkeley: a time when many of the privileged Bay Area hippies grew tired of playing at being poor and either resettled, en masse, in Mill Valley, or seized up ll the old Victorian houses around Berkeley and renovated them. Most of these post-'60s hippies looked a great deal like the cast of this movie.

But I digress.

Let’s Scare Jessica to

Death is largely a mood-piece vampire film, another in the 1970s female vampire movie trend (Daughters of Darkness, The Velvet Vampire) which cribbed liberally from the 1872 Gothic novel Carmilla by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu that predated Bram Stoker’s Dracula by 26 years. Although it has a couple

of scenes that made me start and got the hairs on my neck to stand up, it’s principally

one of those horror movies I’d categorize as disturbing. It’s

get-under-your-skin creepy rather than jump out of your seat scary. A genuinely

unsettling horror movie that works on a number of levels, all playing to things

like paranoia, the fluidity of reality, and the human capacity to make the ordinary

look sinister if we try hard enough.

To its benefit, Let’s

Scare Jessica to Death tries to do something different with the tropes of

the vampire genre; giving a nod to tradition here and there (whether treated reverentially

or casually, impending death remains a constant presence), but

deviating from the expected in interesting ways. For instance, I like how the

vampire, a bride who drowned just before her wedding 100 years ago, doesn’t

have fangs, wears white, and, in lieu of biting a victim's neck as a means of blood extraction, uses the knife intended for her wedding cake.

Because the film is largely concerned with creating a

haunting mood of menace and dread, not a lot of what occurs actually adds up logically.

But the central conceit of presenting the film from Jessica’s subjective,

arguably splintered, point of view, allows for narrative murkiness to work in

the film’s favor.

|

| Flirting with Death They drive around in a hearse, her husband's cello case looks like a coffin, and Jessica's hobby is visiting graveyards to make tombstone rubbings |

PERFORMANCES

The strength of Zohra Lampert’s performance is so persuasive

that I tend to (mistakenly) regard Let’s

Scare Jessica to Death as a character-based horror film. It’s not, its

characters are sketchily written at best, and while uniformly good, few of the other actors register beyond par-for-the-course for the exploitation horror

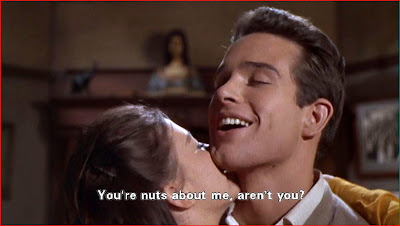

genre. Mariclare Costello brings an assured, assertive quality to a character meant to be enigmatic. The likable Kevin O’Connor (who

portrayed Humphrey Bogart in the truly dreadful 1980 TV-movie, Bogie) falls

victim to tonsorial trendiness: little in the way of a performance is allowed

to emerge from behind those huge sideburns, that enormous mane of styled ‘70s hair, and his Ned Flanders

mustache.

I quite like Barton Heyman (who some might remember as the physician

subjecting poor Linda Blair to all those tests in The Exorcist), as the overconcerned husband. He has several moments

where he conveys a protective fear and resigned sympathy for Jessica that makes

you wish his role were better written.

But the film is unimaginable without the superb Zohra Lampert.

Her Jessica is a Master Class in how an inventive, skilled actor can put ten times more onscreen

than is found on the written page. With almost nothing to work with beyond “neurotic,”

Lampert (Warren Beatty’s shy bride in 1961’s Splendor in the Grass) sidesteps the clichés of the “woman in

peril” and makes Jessica a complex, richly realized, wholly unique (and heartbreaking) character you can’t take

your eyes off of.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Beyond the compelling vulnerability, Zohra Lampert brings to

the character of Jessica, I find myself most drawn to Let’s

Scare Jessica to Death’s sustained atmosphere of dreamlike creepiness. How it's achieved is clearly deliberate in some instances: the unsettlingly calm shots

of the misty cove and surrounding forest; the angled, shadowy claustrophobia of

the farmhouse. In others, it’s just as obviously the result of happy accidents:

the film’s low-rent production values lend the film a turbid, documentary quality

that makes every shot look, to borrow a quote from MST3K, “Like someone’s last

known photograph.”

Another asset, one

that’s proved instrumental to Let’s Scare Jessica to Death's cult reputation, is its

one-size-fits-all ambiguity. Presented with the prospect that all the events we witness are filtered through Jessica's neurotic gaze, the film opens itself up to myriad interpretations.

|

| Lesbian Panic One theory posits that the film is a hallucinatory delusion born of Jessica's friendly/fearful attraction to the sensual Emily |

In making his directorial debut, John D. Hancock (Bang the Drum Slowly - 1973) has cited Henry James' The Turn of

the Screw as a direct influence, yet he also readily admits that several

of the most tantalizingly obtuse elements in the film aren’t exactly pertinent pieces of an intricately thought-out puzzle. If the séance sequence and

the appearance of the mysterious girl in white seem to make no sense and appear to have no connection to the plot, it’s for good reason: both were included at the suggestion of an exhibitor, and the insistence of the producer, respectively.

Such is the interactive magic and power of movies, apropos of the horror genre, especially. If you succeed in engaging the audience on a visceral level, to reach them through means of visual theory and emotional engagement, then their imaginations will always work to fill in the plot holes and gaps of logic. For me, Let's Scare Jessica to Death isn't a horror film that works in spite of it not making much sense, it works specifically because it doesn't make much sense.

|

| The Madwoman in the Attic Let's Scare Jessica to Death shares with other atmospheric Gothics like The Innocents, Rosemary's Baby, and The Haunting, a heroine whose questionable sanity brands her an unreliable narrator. Ironically, by fade-out, most of these films tend to end on a note of "I Believe the Woman." |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Something occurred to me while watching (as much as I could

stomach) the horrorshow that was the 2018 SCOTUS hearings. It occurred to me that

one of the things that has come to most characterize the current American socio-political

climate has been the emergent spectacle of the hysterical male. They’ve always

been around, these bastions of toxic/fragile masculinity, but never before has

there been such a public parade of wild-eyed, blubbering, irrational, excitable,

over-emotional (largely white and heterosexual) men, frothing at the mouth over

an incapability of aligning an antiquated, deluded self-image to an evolving reality.

|

| Eve Was Weak Jessica is about to pick an apple from their recently sprayed orchard before Duncan warns her that it's poison |

When explored in films at all, the phenomenon of the hysterical male has featured most often in the context of the paranoid thriller: films where a disbelieved male (whom the audience knows is actually right) fights a corrupt system. But given their visible abundance in real life, it's surprising to think how seldom the hysterical male appears in horror films.

Given that masculinity is a social construct only slightly less sturdy than the membrane lining an eggshell, it would seem a natural vulnerability topic for the horror genre; but Gothic tradition has long deemed the psychotic woman to be the defining trope of helplessness. When the psychotic man appears in horror, instead of being depicted as a victim or weak figure (which likely wouldn't sit too well with the genre's sizable male fanbase) his hysteria is inevitably framed in terms of his being an agent of violence or figure of fear.

Given that masculinity is a social construct only slightly less sturdy than the membrane lining an eggshell, it would seem a natural vulnerability topic for the horror genre; but Gothic tradition has long deemed the psychotic woman to be the defining trope of helplessness. When the psychotic man appears in horror, instead of being depicted as a victim or weak figure (which likely wouldn't sit too well with the genre's sizable male fanbase) his hysteria is inevitably framed in terms of his being an agent of violence or figure of fear.

The theme of feminine fragility is a common one in horror films,

and Let’s Scare Jessica to Death is

no exception when it comes to Jessica’s tenuous grip on reality being both the focus

of the film’s dramatic tension and the source of the audience’s emotional

involvement. Jessica screams, shrieks, and wails while the men remain at a

stoic, emotional remove. Even when she voices perfectly reasonable concerns

regarding the strange behavior of the townsfolk or the appearance of the girl in

white, the men’s uncurious and dismissive reactions reinforce the

genre’s need to render unreliable a woman’s account of her own experience. In horror, women are emotional, the men are rational and sound.

|

| Screams, whispers, and odd noises punctuate the sound design of Let's Scare Jessica to Death. Another major asset is composer Orville Stoeber's bloodcurdling score. |

Standing in contrast to Gothic traditionalism and the theme of "the disbelieved woman" is the gender-based disruption introduced by the character of Emily. In horror films, a female vampire is depicted in ways not dissimilar to that of the femme fatale in film noir. Her power lies in her awareness of men's vulnerability to her sexual allure. She has both agency and control over her fate because men are such easy prey.

Clip from "Let's Scare Jessica to Death" (1971)

BONUS MATERIAL

|

| In 1980 Mariclare Costello appeared as Mary Tyler Moore's sister-in-law Audrey in the film Ordinary People |

I sit here and I can’t believe that it happened. And yet I

have to believe it.

Dreams or nightmares…madness or sanity. I don’t know which

is which.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)