Toys in the Attic (idiom): Euphemism for insanity. Diminished mental capacity. To think or behave in an immature, foolish, or unreasonable manner [See: Bats in the Belfry].

In the tradition of all good Southern Gothics, that genus of deep-fried melodrama made popular by Tennessee Williams, Eugene O’Neill, and William Inge; Lillian Hellman’s Toys in the Attic is a title from which several meanings can be extracted. Idiomatic (mental illness figures into the storyline); literal (a dysfunctional family’s childhood toys have not been discarded, but remain stored in the attic of their dilapidated home); symbolic (the attic: a place of hidden secrets and childhood preserved. The toys: repressed longings and delicate illusions one is fearful of having shattered); and metaphoric (to avoid reality by means of repression, self-delusion, and clinging possessively to things/illusions of the past).

Hellman’s semi-autobiographical Toys in the Attic was the author/playwright’s last original play following such Broadway successes as The Children’s Hour, The Little Foxes, and Candide. Toys in the Attic was produced on Broadway in 1960 starring Jason Robards, Maureen Stapleton, Anne Revere, and Irene Worth; all nominated for Tony Awards, the show itself, was nominated for Best Play.

Luckily for me, Lillian Hellman wrote her play with swamps, sweet tea, and sweltering sex to spare, so even Production Code-mandated alterations leave Toys in the Attic with plenty of what one hopes to find in a Southern Gothic: sexual repression, heated histrionics, inconsistent Southern accents, neurosis, brass beds, rumpled sheets, electric fans, and loads of family secrets--still in abundant supply.

|

| Dean Martin as Julian Berniers |

|

| Geraldine Page as Carrie Berniers |

|

| Wendy Hiller as Anna Berniers |

|

| Gene Tierney as Albertine Prine |

|

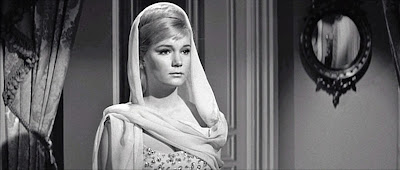

| Yvette Mimieux as Lily Prine-Berniers |

|

| Frank Silvera as Henry Simpson |

Charming, ne’er-do-well Julian Berniers (Martin) has been the doted-on focus of his two spinster sisters his entire life. While Julian chased dream after dream of making a fortune via all manner of half-baked schemes, failed businesses, and gambling binges; practical Anna (Heller) and possessive Carrie (Page) have remained in their hometown of New Orleans, living lives of austere sacrifice, working and maintaining the rundown Victorian home where they all grew up (which, incidentally, none of them ever liked).

Devoid of children, suitors, or even friends, Carrie and Anna are each other’s sole companionship and company, their lives a routine of hollow rituals of false intimacy (weekly, each buys the other an unwished-for gift), buoyed by the twin deferred dreams of selling the house and taking a long-talked-about trip to Europe.

But this time things are different. And the difference shatters the very foundation of dysfunction and delusion upon which the Berniers household has been built.

Toys in the Attic (along with that other 1963 release, William Inge’s The Stripper) came at the tail end of Hollywood’s love affair with Midwest melodrama and sweaty tales of the oversexed South. If 1951’s A Streetcar Named Desire represented the apogee of the genre’s popularity, it’s safe to say that twelve years hence, the tropes and clichés of Southern psychodrama had begun to wear thin. Toys in the Attic enjoyed success on Broadway, but by the time it reached the screen, foreign films had so surpassed American films in both frankness and realism, the mannered theatrically and compound coyness of Southern Gothic was beginning to feel a little passé.

In adapting the play to the screen, Lillian Hellman purists may have balked at the subplots and characterizations sacrificed to screenwriter James Poe whittling Hellman’s 2-hour-plus play down to a taut 90-minutes; but given the over-familiarity of the play’s by-now well-traveled themes of sex, eccentricity, and decay, I’m not certain the film could easily have supported a longer running time.

By 1963, censorship had relaxed enough so that Toys in the Attic didn’t have to completely commit to the kind of avoidance games that neutered 1958’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof—for example, the word “incestuous” is never referred to in regard to Carrie's unhealthy preoccupation with her brother, but the euphemistic term “sleep with” is bandied about freely. Poe’s adaptation updates the play from the Depression Era to modern-day New Orleans, and in doing so minimizes the significance of Tierney’s perceptive character; eliminates all mention of Julian’s bouts of sexual impotence; erases hints of Anna’s latent incestuous feelings for her sister; does the best as it can with an interracial romance (proximity within the frame has to substitute for physical intimacy), and changes the character of Lily from being developmentally challenged (giving credence to her fears that her mother [Tierney] paid Julian to marry her) to being merely emotionally immature.

From early trade paper reports attaching the names William Wyler, Katharine Hepburn, Vivien Leigh, and Olivia de Havilland to the film, there’s a sense that Toys in the Attic went through a lot of changes before reaching the screen. Likely, some of them budgetary. For a time, it was believed serious dramas should be filmed in black and white, the color adaptions of Tennessee Williams’ Summer and Smoke (1961) and Sweet Bird of Youth (1962)—both starring Geraldine Page—flying in the face of that tradition. By 1963 fewer films were being made in black and white, so it’s not clear if the beautiful black and white cinematography of Toys in the Attic (by Joseph F. Biroc) was inspired by aesthetics or budget. What is known is that television-trained director George Roy Hill (making his second film, his first being the [rare]Tennessee Williams comedy Period of Adjustment in 1962) was used to working fast, cheap, and in black and white.

|

| Toys in the Attic's sole Oscar nomination was for Bill Thomas' costume designs. Thomas won the Oscar in 1961 for Spartacus |

If the final cast chosen for the film lacked the marquee allure of Wyler’s involvement, they certainly didn’t lack for prestige. Toys in the Attic marked Oscar and Tony nominee Geraldine Page’s third foray into Southern Gothic; Tony-nominated and Oscar-winning British actress Wendy Hiller (for Separate Tables) made an ideal match to play Page’s circumspect sister, and Gene Tierney (Oscar-nominee for Leave Her To Heaven, and whose real-life struggles with mental illness brought about her premature retirement in 1955) was in the midst of a welcome comeback following her appearance in Otto Preminger’s Advise and Consent (1962).

But from the time casting was first announced to the film’s release in the summer of 1963, the biggest topic of conversation and critical bone of contention surrounding Toys in the Attic was the casting of actor/entertainer Dean Martin in the role that had won Jason Robards a Tony nomination. Martin was no stranger to movies, having appeared in more than 20 features by the time he was cast opposite such theatrical veterans as Page and Hiller. It was simply that few had confidence that the lightweight, notoriously easygoing half of the Martin & Lewis comedy team had the range and dramatic chops to tackle this, the most substantial of his rare dramatic screen appearances.

Toys in the Attic was not a success, in fact, it was a resounding flop. Critics, citing battle fatigue over the whole clutch-the-pearls-while-I-fan-myself genre, called it a minor Southern Gothic and complained that James Poe’s adaptation undercut the complexity of Heller’s characters and supplanted the play’s pessimistic conclusion with a provisionally “happy” ending. Even George Roy Hill was dissatisfied with the result, calling the film the least successful of his works. And while Page and Hiller emerged with their reputations intact, critical response to Martin’s performance was so harsh he never tackled so sizable a dramatic role again.

|

| Such Devoted Sisters |

I recently got my hands on a copy (first time seeing it in decades) and was pleased to discover it to be even better than I remembered. Sure, it's no The Little Foxes, yet it tells its story with an economy and visual style that perfectly serves its tone of mounting suspense and escalating tensions. It's a dynamic, emotionally rich showcase for the talented cast and a great many Southern Gothic clichés, ultimately managing to enthrall and entertain in spite of its flaws.

|

| Nan Martin as Charlotte Watkins |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

Much of Toys in the Attic is said to be autobiographical, down to Hellman setting the story in her hometown of New Orleans, basing the character of Julian on her salesman father (who had two clinging sisters), referencing an aunt who had an affair with her African-American chauffeur, and, as per the play’s themes of latent incest, drawing upon her own adolescent feelings towards an uncle.

I credit this as the reason why the relationships in Toys in the Attic resonate with so much emotional authenticity. Even when the sometimes-overreaching aspects of a melodramatic subplot—involving a land swindle and an emotionally abused wife (Nan Martin) seeking escape—threaten to overwhelm the proceedings, what remains compelling are the complex dynamics in the relationship between the three siblings, and the threat Lily poses as a clingy interloper in their long-established cycle of dysfunction.

|

| The selfish, crippling side of love rears its head when the always-in-need-of-rescue Julian finds someone who needs him. |

Like Julian, I am the only boy in my family. While I was never exactly doted on by my four sisters, I remained somehow shielded and apart from the tensions and issues they shared amongst themselves; a fact which engendered resentment from some, envy in others. There was no lack of love between us, but the way we were viewed and related to by our parents (I could do no wrong, my sisters fell under strict scrutiny) affected how we viewed and related

What I most responded to in Toys in the Attic is how it captures the curious way some families can handle the failures of its members with far more generosity and grace than they do the successes. How living with unhappiness (as long as it means things will remain unchanged) can be a less frightening prospect to people than taking the kinds of risks that can bring about true happiness.

|

| Confrontations and Confessions "When you love, you take your chances on being hated by speaking out the truth." |

If you don’t like Geraldine Page, I doubt you’ll much care for Toys in the Attic. She’s the entire show. And what a show it is. Wendy Hiller (underplaying nicely and turning stillness into an art) is the grounded center around which Page’s Tasmanian Devil of a faded southern belle spins uncontrollably and destructively. Playing a delusional, manipulative character whose life of peculiarly selfish selflessness has left her a throbbing mass of unrecognized desires, Page is simply forceful and more than a little frightening.

|

| Baby Doll What's a Southern Gothic without a brass bed and rumpled sheets? |

Yvette Mimieux suffers more from how her character is written than from anything specific I can cite in her performance. Perhaps because Mimieux had just come off of a film in which she played a developmentally challenged girl (Light in the Piazza -1962), the filmmakers decided to drop that angle of her character completely. Unfortunately, without her mental capacity being called into play, her Lily, now written as being simply naive and immature, winds up coming across as a bit of a nitwit. Mimieeux is very effective in the role, but as for the character --I'm afraid that with her grasping behavior and moping countenance, Lily becomes an annoying presence long before she has the opportunity to become a sympathetic one.

Gene Tierney is a welcome sight and is very good (and charmingly funny) in a small role requiring the 41-year-old actress to look believably older than 44-year-old Dean Martin. The film doesn't exactly succeed on that score, but Tierney and the dashing and dignified Frank Silvera do make for a very a handsome couple.

I thought Dean Martin was surprisingly good as Julian. He's an actor of limited range, to be sure, but he doesn't embarrass himself and has moments so good that he makes me wish he had tried his hand at dramatic roles more often. Admittedly, I did find myself imagining from time to time the kind of depth and nuance Jason Robards might have brought to the role, but in the end, I had to concede that Martin brings a kind of effortless charm and boyish exuberance to the role that I can't really imagine in Robards.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

By way of a striking visual style that emphasizes the dominating and confining aspects of the Berniers home, Toys in the Attic finds a deft way of expounding on the film's theme of emotional and self-imprisonment.

|

| Fearful that Julian is having an affair and feeling unwelcome by his sisters, Lily's isolation is dramatized in this shot which makes the childlike woman appear to be standing in an oversized crib. |

|

| Many scenes are shot from an attic's eye view, the characters minimized and dominated by the house |

|

| Again, the characters are filmed in ways to make them appear caged in and confined by the house |

Movie trends inevitably suffer from oversaturation, resulting in perfectly fine films being rejected by critics and the public alike due to the genre's cycle having run its course. Distanced from what in 1963 must have looked like yet another go-round of decorous depravity and decay told with wavering southern accents; Toys in the Attic appears now to be a seldom-discussed film (no minor classic, but entertaining and well-made) worthy of reappraisal.

Wendy Hiller and Geraldine Page in a clip from Toys in the Attic (1963)

|

| In 1960, Wendy Hiller starred in the London production of Toys in the Attic, playing the Geraldine Page role. |