Warning: Spoiler Alert. This is a critical essay, not a review. Therefore, many crucial

plot points are revealed and referenced for the purpose of analysis.

“Dying is easy. Playing a lesbian is hard.”

Fictional actress Debbie Gilchrist, co-star of Home for Purim in Christopher Guest’s For Your Consideration (2006)

I really love suspense thrillers, but good ones are extremely hard to come by. Far too often, pretenders to the title fall short on both suspense and thrills due to predictable plotlines and a near-devout adherence to the structural conventions of the genre. It's a common writer's pitfall that suggests to me someone has invested in too many of those How to Write a Winning Screenplay workshops that offer enrollees a downloadable “Surefire Suspense Thriller” PDF template.

Granted, not many directors understand storytelling, the

language of cinema, or the rudiments of building suspense as keenly as Alfred

Hitchcock, Henri-Georges Clouzot, Roman Polanski, or Claude Chabrol. But one always harbors the hope that, should a filmmaker endeavor to try their hand at the genre, they do so with some understanding of the fundamentals. Without such a foundation, the alternative is invariably a suspense thriller that trades mystery and plot twists for contrivance,

coincidence, and implausibilities.

Windows is a movie of firsts and lasts: Windows is the first and last film to be directed by famed cinematographer Gordon Willis (The Godfather, Annie Hall). It’s the first & last screenplay to be written by one Barry Siegel (not to be confused with the Pulitzer Prize-winning LA Times journalist). It's the last major motion picture to feature up-and-coming The Godfather/Rocky alumna Talia Shire in a lead role--Windows being the three-strikes-you’re-out, last-straw flop that followed on the heels of the underperforming features Old Boyfriends (1979) and Prophecy (1979).

It's the major motion picture debut of co-star Joe Cortese, who had heretofore only appeared in indies. And finally, Windows has the dubious

distinction of being the first film to be released in 1980 (January 18th), but,

seeing as it was pulled from theaters almost immediately after the near-unanimous

critical drubbing it received, it's a good guess Windows also wound up as the last entry in 1980's year-end boxoffice tallies.

|

| Talia Shire as Emily Hollander |

|

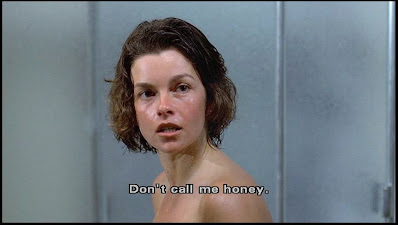

| Elizabeth Ashley as Andrea Glassen |

|

| Joe Cortese as Detective Bob Luffrono |

Shy, stammering Emily Hollander (Shire) works in some

mysterious capacity at the very picturesque Brooklyn Children’s Museum. Though we

never find out exactly what she does there, we do learn that her co-worker is

her husband and that they are soon to be divorced. Where Emily lives is picturesque too, her apartment being in

a quaint Brooklyn Heights brownstone huddled, troll-like, beneath the Brooklyn

Bridge. She shares this tiny apartment with a cat, a closet full of look-alike

outfits, and several volumes of books devoted to the subject of stuttering. We're left to do what we will with all this visual backstory, for the film refuses to disclose anything which might provide a clue as to why she's so timorous or why her fashion sense runs to Italian Tzniut.

|

| We know Emily regularly sees a therapist and that she struggles with a stutter. What we never find out is why Emily, like Olive Oyl, has a closet full of the exact same outfit. |

Returning home one evening after work, Emily is assaulted in her apartment by a man wielding a switchblade and a mini tape recorder. In a very difficult-to-watch scene, Emily is terrorized and

sexually humiliated (not raped, as many critics thought at the time) by her assailant, her frightened

pleas recorded for some kind of perv posterity. This roughly 2½ minute sequence feels like it goes on for an eternity. And as you sit there squirming in your seat, wishing maybe Rocky Balboa would show

up to kick some ass, somewhere in the back of your mind you’ve

arrived at a concrete certainty: you’re certain that nothing that follows in

this film (that’s now only 8-minutes old) will ever—no matter how masterfully

done—justify this scene.

Physically unharmed but emotionally shattered, Emily reports the assault to a sensitive Italian police detective named Bob (cow-eyed Joe Cortese), but is understandably reluctant to go into details. Enter husky-voiced, over-solicitous neighbor and friend Andrea Glassen (Elizabeth Ashley), an affluent poet whose obscenely large and equally picturesque apartment in the same building suggests Emily is perhaps renting a closet. (Truth be told, Andrea may inhabit the same apartment building or live several miles away. For all the time invested in providing painterly images of New York, Windows takes a rather relaxed attitude when it comes to establishing location and proximity.)

Physically unharmed but emotionally shattered, Emily reports the assault to a sensitive Italian police detective named Bob (cow-eyed Joe Cortese), but is understandably reluctant to go into details. Enter husky-voiced, over-solicitous neighbor and friend Andrea Glassen (Elizabeth Ashley), an affluent poet whose obscenely large and equally picturesque apartment in the same building suggests Emily is perhaps renting a closet. (Truth be told, Andrea may inhabit the same apartment building or live several miles away. For all the time invested in providing painterly images of New York, Windows takes a rather relaxed attitude when it comes to establishing location and proximity.)

|

| Emily's soon-to-be ex-husband, Steven (Russell Horton), installing a display at the Children's Museum |

While the traumatized Emily sits silently grappling with her feelings, Andrea spends her time shooting officer Bob lots of stony glances until either futility or boredom causes him to leave. In a refreshing departure from the usual suspense thriller gambit that contrives for a terrorized protagonist to remain living at the scene of the crime in order to better facilitate encore

visits from the assailant, Windows has

Emily hightailing out of her apartment the very next day and moving into a picturesque

(what else?) Bridge Tower apartment across the river. A place with a spectacular view, ginormous picture windows, and a convenient shortage of drapes.

(You’ve been warned, spoilers to follow.)

It seems Andrea is a lesbian pathologically and psychotically in love with Emily. Andrea's romantic scheme to win her lady love is to hire a cab driver to sexually assault Emily in the hope that the trauma will: (1) turn Emily off men for good, (2) send Emily rushing into her arms for protection and comfort, sparking a love/gratitude romance (3) all of the above. (How the hell did Andrea find a sicko for such a job, by looking through the Yellow Pages?)

*Note to hetero screenwriters creating gay characters: “That’s not how it

works. That’s not how any of this works.”

|

| Windows is the last film appearance of Oscar-nominated Funny Girl co-star Kay Medford. She portrays kind but apprehensive neighbor, Ida Marx. Who shares Emily's fashion sense |

Once Emily moves away and begins a hesitant and intensely dull love affair with Detective Bob, Andrea--because the whole New York housing shortage must be a myth--quickly secures herself a loft

directly across the river from Emily's apartment, and (relying heavily on Emily never purchasing blinds) watches the object of her

affections through a telescope while getting off to the tape-recorded cries and moans of Emily’s assault. Fun gal, that Andrea.

With the “whodunit” out of the way, you'd think Windows would devote its time then to exploring motive and character—a valid

concern given that we're shown precious little about Emily to warrant interest, let alone obsession—but instead, the film opts for atmosphere over content. The characters may remain vague and ill-defined, but New York has never looked as picturesque and moody (by now you've gathered that "picturesque" is the film's defining dramatic motif).

|

| The Eyes of Rick Petrucelli, aka the assailant |

To remind us that we're still watching a thriller, Windows throws in a couple of off-screen murders and a scene of Emily discovering something unpleasant in her freezer wedged between the broccoli spears and Cool Whip. But for the most part, suspense is limited to wondering just how Nutso-Bismol Andrea is going to go before the inevitable showdown. A showdown brought about by the screenwriter having the characters do the absolute dumbest things possible at the absolute worst time.

|

| "Hello, Police? I just happened to catch a cab driven by the man who assaulted me...what should I do?" "Get back in the cab and have him drive you to the police station." "Oh, OK...will do!" |

The arch dialogue may be mine, but I swear, this actually happens in the film!

Although falling woefully short of the mark by comparison, the movie Windows most obviously attempts to

replicate is Alan J. Pakula’s masterpiece of paranoid urban dread Klute (1971), a suspense thriller in which Gordon Willis’ evocative

painting-with-shadows cinematography is used for more than creating pretty pictures. Like Windows,

Klute’s mise en scène is New York as a

claustrophobically alienating city devoid of intimacy, and at the center, there's a tentative romance between a detective and a woman terrorized by a would-be assailant equally fond of tape recorders. But that's where the

similarities end.

Klute revitalized the standard detective thriller through its subjective visual style and character-study approach to its protagonists. Windows’ screenplay feels like it’s either a few story conferences short of a concrete approach or the victim of extensive editing. Behind the tired "scheming lesbian" trope, there exists a rather harrowing crime, committed by proxy. Yet, nothing about how the film unfolds aligns the bizarre nature of its premise with what seems to be a simple, not particularly profound desire to say something about alienation, identity, and the inarticulate human struggle to connect.

|

| Andrea's therapist (Michael Lipton) questions her about the authenticity of her love for Emily "Have you said how you feel?" "I will. I...I mean, I can't yet...but I will." |

With Emily, there’s her stutter, her inability to make her feelings known to her ex-husband, and the noncommunicative wariness of her new neighbors. The tape recorder used during Emily's assault reinforces this "vocal" theme, as does the assailant centering his knife threats in the region of her mouth and throat. As for Andrea, she has trouble communicating

with her therapist, expresses herself emotionally only through poetry, engages

in voyeurism and ecouteurism (sexual arousal by listening), and, despite her wealth and good looks, clearly has a

problem landing a date.

Add to this the echoing visual motifs of windows, glass, lenses,

reflective surfaces, and the themes of watching and being watched, and you're bound to feel certain that Windows has a distinct point

to make about it all. For a movie named Windows, there's an awful lot about it that's not very clear.

Windows is a classic example of all style and no content. So much obvious care and thought have been given to how the film looks and the ways windows can be literally and figuratively worked into the narrative. But it's the narrative itself that feels the flimsiest and least thought-out. By the time Windows limps to its conclusion, it actually comes as something of a surprise that all this curated weirdness has failed to add up to anything substantive.

|

| Every move you make, every step you take, I'll be watching you The hit song by The Police was released in 1983, but it fits Windows to a T |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

As tends to be Hollywood's irresponsible wont, when it "discovers" gay people, it can only think to feature them in mainstream movies in the most sensational, exploitative ways possible. That's why 1980 saw the controversial release of two movies featuring violently psychopathic gay characters within one month of each other. January brought the psychotic lesbian of Windows, while William Friedkin's Cruising, slated for February release, granted us another film featuring a homicidal homosexual. Although Windows garnered its share of controversial press, advance word-of-mouth about the film was so poor that picketers didn't even bother to show up when I saw it on opening night.

I remember being less concerned about the controversy than I was overwhelmed at the prospect of what I was about to see. Anticipation was at an all-time high for I had worked myself into a frenzy thinking that Windows was going to be as scary as Klute, gritty as Looking for Mr. Goodbar, and as stylish as Eyes of Laura Mars. I had thoroughly convinced myself that this was going to be something really special. Advance word-of-mouth be damned.

Did Windows measure up to my expectations? Well, I'd be lying if I said I didn't enjoy it. Indeed, I sat through it twice. But it wasn't because it was such a great thriller; I was riveted to my seat by the sheer weirdness of it all. It reminded me of that scene in Young Frankenstein when Igor drops the genius brain resulting in an abnormal brain ("Abby someone...Abby Normal") being inserted into the monster by mistake. Windows feels like the studio assembled an A-list cast and crew, sunk a lot of money into the budget, but at the last minute somebody slipped in a script for a low-rent, mid-'70s, grindhouse rapesploitation flick.

The one-two punch of Cruising and Windows appeared to be a harbinger of the decade to come. A time when Hollywood seemed primed to trade one dehumanizing, negative stereotype--the scary urban ethnics of the Dirty Harry and Death Wish '70s--for another--the homosexual as degenerate predator and killer--for the sake of a sensationalist buck.

To put such offensiveness into context, it was bad enough that this unimaginative wave of cliche felt like a conservative negation of the pro-sex, gay-liberation vibe of the sexual revolution of the previous decade; but in so associating homosexuality with death, the timing couldn't have been worse, what with the specter of AIDS looming on the horizon of 1981. Inclusion certainly involves gay characters being allowed to be the heavy in movies, but the larger issue is one of proportion

With so few depictions of gay characters onscreen at all, there is something inarguably problematic about narratives that cast gays (in real life, the traditional targets of bullying and hate-crime violence at the hands of heterosexuals) as the agents of homicidal threat to victimized straights.

As the '70s came to a close, gay characters in films were still depicted mainly in either comic or derogatory terms, so as far as I was concerned, the gay community was right to protest this rare instance in which you have two major releases with prominent gay characters, and in both they are depicted as pitiable psychopaths. Windows was so widely panned and dismissed that I honestly don't think it was still in theaters by the time Cruising opened just four weeks later on February 18th.

The distancing of time has made Windows considerably less offensive for me. Certainly less sensational. It's hard to work up too much steam over the absurdly written character of Andrea...she's more representative of a plot contrivance than a real person.

I'm a big fan of Elizabeth Ashley, but it surprises me to think that outside of a TV movie or two, I've only seen her in this, Coma, and Ship of Fools. She has an intensity that makes her always interesting to watch, plus a kind of Susan Hayward propensity for overacting that challenges the believability of her characterizations. Playing a can't-win role, Ashley is really not that bad. Short of resorting to that "unblinking stare" thing that movie lesbians have been doing since Candice Bergen trained her gaze on Joanna Pettet in The Group, her stereotypically-written role is mercifully devoid of grand "I'm a lesbian!" acting indicators. The screenplay does her no favors in the final scenes (where she's left to go right over the top without a net), but she definitely has her moments and her performance looks better to me now than it did in 1980.

Although Windows has an impressive pedigree and the odd cult cachet of being a film few people have liked, heard about, or seen, it's not, for me anyway, an undiscovered classic. What it does have is the stamp of being a visually stylish '70s-into-the-'80s curio which manages to be, by turns, both engrossing and off-putting.

BONUS MATERIAL

In 2007, Talia Shire appeared in a series of commercials for GEICO.com in which she portrayed a therapist to one of those cavemen that were so popular for 15 minutes back in the day—even getting their own ill-advised, short-lived sitcom. Shire playing the silliness absolutely straight is really rather marvelous.

Commercial #1

Commercial #2

Commercial #3

Paperback tie-in novels adapted from screenplays were once a popular part of movie marketing. The novelization of Barry Siegel's screenplay for Windows was written by H.B. Gilmour. Gilmour carved out quite a career novelizing screenplays, a few of her many other paperback adaptations being: Saturday Night Fever, All That Jazz, and Eyes of Laura Mars

THE AUTOGRAPH FILES

Gordon Willis died in 2014 at the age of 82. This autograph is from 1984, when I was a dance extra in the truly awful John Travolta/Jamie Lee Curtis aerobics movie Perfect (1985), for which Willis served as cinematographer. Some of his other more distinguished films are: Annie Hall, All the President's Men, The Parallax View, Pennies from Heaven. Considered one of the most influential cinematographers of the '70s, he was nominated only twice (Zelig, The Godfather III) and was awarded an honorary Oscar in 2010.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2017

As the '70s came to a close, gay characters in films were still depicted mainly in either comic or derogatory terms, so as far as I was concerned, the gay community was right to protest this rare instance in which you have two major releases with prominent gay characters, and in both they are depicted as pitiable psychopaths. Windows was so widely panned and dismissed that I honestly don't think it was still in theaters by the time Cruising opened just four weeks later on February 18th.

The distancing of time has made Windows considerably less offensive for me. Certainly less sensational. It's hard to work up too much steam over the absurdly written character of Andrea...she's more representative of a plot contrivance than a real person.

|

| The film's windows/lenses motif is carried over to Andrea's Brobdingnagian eyewear |

PERFORMANCES

Years after having made Windows, director Gordon Willis

expressed regret at having made the film, calling it a mistake. One big mistake I can attest to is the decision to have Talia Shire more or less play the character of Emily as a "greatest hits" reprise of her Oscar-nominated

performance in Rocky. Shire’s Emily

is a veritable portfolio of self-conscious gestures, downcast eyes, halting

whispers, and fleeting half-smiles tucked into a knit hat. As much as I like

Talia Shire (and I like her a great deal), her Xerox performance here had me feeling, at

least the first twenty minutes or so, that Windows

was the darkest, most surreal Rocky sequel

ever made.

|

| I think the cautious romance between Emily and Detective Bob is supposed to be touching, but at times, they seem like they're mere moments from pledging a suicide pact |

I'm a big fan of Elizabeth Ashley, but it surprises me to think that outside of a TV movie or two, I've only seen her in this, Coma, and Ship of Fools. She has an intensity that makes her always interesting to watch, plus a kind of Susan Hayward propensity for overacting that challenges the believability of her characterizations. Playing a can't-win role, Ashley is really not that bad. Short of resorting to that "unblinking stare" thing that movie lesbians have been doing since Candice Bergen trained her gaze on Joanna Pettet in The Group, her stereotypically-written role is mercifully devoid of grand "I'm a lesbian!" acting indicators. The screenplay does her no favors in the final scenes (where she's left to go right over the top without a net), but she definitely has her moments and her performance looks better to me now than it did in 1980.

Although Windows has an impressive pedigree and the odd cult cachet of being a film few people have liked, heard about, or seen, it's not, for me anyway, an undiscovered classic. What it does have is the stamp of being a visually stylish '70s-into-the-'80s curio which manages to be, by turns, both engrossing and off-putting.

In 2007, Talia Shire appeared in a series of commercials for GEICO.com in which she portrayed a therapist to one of those cavemen that were so popular for 15 minutes back in the day—even getting their own ill-advised, short-lived sitcom. Shire playing the silliness absolutely straight is really rather marvelous.

Commercial #1

Commercial #2

Commercial #3

Paperback tie-in novels adapted from screenplays were once a popular part of movie marketing. The novelization of Barry Siegel's screenplay for Windows was written by H.B. Gilmour. Gilmour carved out quite a career novelizing screenplays, a few of her many other paperback adaptations being: Saturday Night Fever, All That Jazz, and Eyes of Laura Mars

THE AUTOGRAPH FILES

Gordon Willis died in 2014 at the age of 82. This autograph is from 1984, when I was a dance extra in the truly awful John Travolta/Jamie Lee Curtis aerobics movie Perfect (1985), for which Willis served as cinematographer. Some of his other more distinguished films are: Annie Hall, All the President's Men, The Parallax View, Pennies from Heaven. Considered one of the most influential cinematographers of the '70s, he was nominated only twice (Zelig, The Godfather III) and was awarded an honorary Oscar in 2010.