On the occasion of having completed a collection of Agatha

Christie mystery novels gifted to me by my partner at Christmas (in hardback

yet!), I’ve taken the opportunity to revisit 1978’s Death on the Nile, the second film in the unofficial

Poirot Trilogy from British producers John Brabourne and Richard Goodwin (Murder on the Orient Express -1974, Death on the Nile -1978, Evil Under the Sun - 1982).

Released in the fall of 1978 at the height of America's Tut-Mania born of the 1976-1979 tour of The Treasures of Tutankhamun museum exhibit, Death on the Nile was a less stylish,

not quite all-star follow-up to the wildly successful Murder on the Orient Express, and marked the first appearance of Peter

Ustinov as Hercule Poirot. It seems Albert Finney declined the opportunity to

reprise his Oscar-nominated performance from that first film after considering

the rigors of applying and wearing the extensive Poirot makeup and prosthetics in

the triple-degree heat of the Egyptian desert.

Lacking, for my taste anyway, the star quality Finney brought to the role which made him more an equal participant in the proceedings, Ustinov nevertheless brings a character actor’s zest to his interpretation of Poirot, making the character uniquely his own. Ustinov would go on to play Christie’s Belgian sleuth in two more feature films (Evil Under the Sun and the awful-beyond-imagining Appointment With Death) and three contemporized TV-movies.

Lacking, for my taste anyway, the star quality Finney brought to the role which made him more an equal participant in the proceedings, Ustinov nevertheless brings a character actor’s zest to his interpretation of Poirot, making the character uniquely his own. Ustinov would go on to play Christie’s Belgian sleuth in two more feature films (Evil Under the Sun and the awful-beyond-imagining Appointment With Death) and three contemporized TV-movies.

|

| Peter Ustinov as Hercule Poirot |

|

| Bette Davis as Mrs. Marie Van Schuyler |

|

| David Niven as Colonel Race |

|

| Mia Farrow as Jacqueline De Bellefort |

|

| Simon MacCorkindale as Simon Doyle |

|

| Lois Chiles as Linnet Ridgeway |

|

| Jack Warden as Dr. Bessner |

|

| Angela Lansbury as Mrs. Salome Otterbourne |

|

| George Kennedy as Andrew Pennington |

|

| Maggie Smith as Miss Bowers |

|

| Jon Finch as Mr. Ferguson |

|

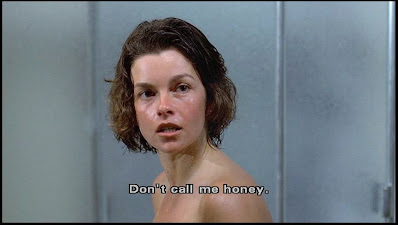

| Olivia Hussey as Rosalie Otterbourne |

|

| Jane Birkin as Louise Bourget |

As a huge fan of Murder

on the Orient Express but having missed the opportunity to catch it on the

big screen, I made sure to see Death on

the Nile the day it opened. I recall the audience as being sparse but

appreciative, and I remember enjoying the film a great deal; albeit more for

its cast and surprising twists of plot (it’s quite a puzzler of a mystery and

hands-down the bloodiest film in the series) than anything particularly noteworthy about its

execution.

Murder on the Orient Express

was a glamorous, cinema-inspired recreation of an era, purposefully romanticized and steeped in nostalgia. Death on the Nile, under the journeyman, traffic-cop guidance of large-scale logistics director John Guillermin (The Towering Inferno, King Kong), is,

on the other hand, a murder mystery well-told, but one devoid of either mood or

atmosphere. The claustrophobic tension of a luxury passenger train is traded

for the more scenic vistas offered by a majestic paddle steamer cruising down

the Nile. Anthony Powell’s dazzling, Academy Award-winning costume designs do

most of the heavy-lifting in the glamour department; meanwhile, the visual splendor of the

British countryside and sunny, travelogue-worthy scenes of Egyptian landmarks

offset the film's otherwise straightforward, TV-movie presentation.

Putting the best

spin on it possible, Death on the Nile’s competent but indifferent

direction and utter lack of visual distinction immediately put to rest any inclination

on my part to compare this film to its (again, to my taste) far superior predecessor. Divested

of any expectation to duplicate that film’s elegant, diffused-light visual style

or compete with its first-class pedigree cast, I was able to better appreciate Death

on the Nile on its own modest, nonetheless worthwhile, merits.

Intelligently and wittily adapted by

playwright Anthony Schaffer (Sleuth)

from Christie’s 1937 novel (which

began life as a stage play alternately titled, Moon on the Nile and Murder

on the Nile), Death on the Nile finds Poirot (Ustinov) vacationing in Egypt aboard a river vessel jam-packed

with potential victims and suspects. The guests include: Poirot’s distinguished friend Colonel Race

(Niven), an imperious dowager (Davis) and her mannish nurse (Smith); a dipsomaniacal romance novelist and her soft-spoken daughter (Lansbury

and Hussey); a pompous Austrian physician (Warden); a peevish Socialist (Finch);

a calculating American lawyer (Kennedy); a rancorous French maid (Birkin); and a too-rich, too-beautiful, too-happy couple on their honeymoon, (Chiles

and MacCorkindale). Oh, and there's also a vengeful scorned woman (Farrow), MacCorkindale's former fiance.

As is to be expected, not a single soul aboard the good ship Karnak is there merely by chance, each life connecting and intersecting in the most intriguing, mysterious ways. The fun to be had in Death on

the Nile is seeing these diverse personalities clash. The entertainment is found

trying to stay one step ahead as the details of the masterfully intricate

mystery at the center of the story come to be revealed.

|

| Bette Davis looks to be channeling a future Maggie Smith in Downton Abbey, while Maggie Smith is putting out a serious Tilda Swinton vibe |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT

THIS FILM

Death on the Nile

is one of those movies that plays much better today than when it was released.

When Murder on the

Orient Express opened in 1974, its all-star cast and artful recreation of a

bygone era rode the crest of the '70s nostalgia craze and the public mania for star-studded

disaster films. But by the time Death on

the Nile was made, the cultural climate had changed significantly. Thanks

to the popularity of the TV miniseries, the guest star face-lift parade that was The Love Boat, and the last gasps of the disaster film mania (Airport

77, The Swarm, Avalanche): all-star casts no longer

meant glamorous...they became synonymous with cheesy.

And while not officially a sequel to Murder on the Orient Express (although conceived as one) Death on the Nile was perceived as a sequel in the minds of the public, and thus also fell victim to the overall cultural disenchantment with the glut of uninspired sequels Hollywood churned out in hopes of duplicating earlier successes: The Godfather Part II, Jaws 2, The French Connection II, The Exorcist: The Heretic.

And while not officially a sequel to Murder on the Orient Express (although conceived as one) Death on the Nile was perceived as a sequel in the minds of the public, and thus also fell victim to the overall cultural disenchantment with the glut of uninspired sequels Hollywood churned out in hopes of duplicating earlier successes: The Godfather Part II, Jaws 2, The French Connection II, The Exorcist: The Heretic.

People seeing Death on

the Nile today see the classic stars of All About Eve, My Man Godfrey (David Niven, the 1957 remake), The

Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Rosemary’s Baby, The Manchurian Candidate, Romeo and

Juliet, and The Great Gatsby, all appearing in the same film. But back in 1978,

the film's biggest stars, Bette Davis and David Niven, were appearing on TV or in low-rent Disney

movies, Peter Ustinov was best known as "That old dude in Logan's Run," Mia Farrow had not yet hitched her wagon to Woody Allen, Angela

Lansbury was better known on Broadway, and George Kennedy was like the James Franco

of the disaster genre: unavoidable and seemingly in everything.

Time has been kind, however, and the biggest treat now is being able to enjoy all

these great stars - many of them no longer with us - in a handsomely-mounted old-fashioned film, looking so

outrageously young, entertaining us with the kind of marvelous, once-in-a-lifetime talent it was once so

easy for us to take for granted.

|

| Swag If you ain't got elegance you can never, ever carry it off |

PERFORMANCES

Just to lodge two main performance complaints from the getgo: 1) Lois Chiles is drop-dead gorgeous, but I've never understood how she landed so many plum roles in high-profile films. When it comes to flat line readings, she really gives Michelle Phillips (Valentino) a run for her money. 2) Simon MacCorkindale's performance would have improved tenfold had he just been given a scene or two sans shirt or in bathing trunks. It certainly did wonders for Nicholas Clay's characterization in Evil Under the Sun.

|

| Dressed to Kill |

As a fan of bitchy dialogue, I find every scene with Bette Davis and Maggie Smith to be pure gold. Their pairing is genuinely inspired. Jack Warden is the master of comical bluster, George Kennedy cleaned up isn't half bad, and I like seeing Mia Farrow and Lois Chiles reunited—they played best friends in 1974s The Great Gatsby—their roles here casting Farrow as a Gatsby-esque character losing her true love to the dazzle of wealth. It helps that Farrow is much more compelling as a woman on the edge than she was as Gatsby's dream girl.

|

| The radiant Olivia Hussey (last seen sliding around on bookcases in Lost Horizon) and the late Jon Finch. Finch, looking thinner here than he did in Macbeth, was diagnosed with diabetes in 1974. |

Even after having read three Hercule Poirot novels, my mental image of the detective is not so defined as to find any fault with Ustinov's portrayal. Although I personally prefer Finney, Ustinov's more sensitive take on the detective (he has a marvelously heartbreaking exchange with Farrow near the end) is quite good.

Although I read somewhere that the actress feels she went a little over the top in the theatricality of her performance, I absolutely adore Angela Lansbury in this. Light years away from Murder She Wrote's Jessica Fletcher or her Miss Marple in 1980's lamentable The Mirror Crack'd (but with a hint of Sweeney Todd's Mrs. Lovett) Lansbury's tipsy romance novelist: "Snow on the Sphinx's Face", "Passion Under the Persimmon Tree" - is the comic highlight of the film for me.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Death on the Nile's only Oscar win is also its only Academy nod. Anthony Powell won Best Costume Design for his eye-popping period creations; costumes that indelibly establish the identities of each member of the sizable cast with style, wit, and considerable theatrical panache. Although I'm surprised to learn his equally astonishing designs for Evil Under the Sun failed to get a nomination, as a six-time nominee and three-time winner (Travels With My Aunt, Tess, Death on the Nile), I don't suppose Powell is losing any sleep over it.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

There's a sense of one having one's cake and eating it too when I think of how I only recently came to read the works of Agatha Christie so many years after first seeing the film adaptations. I was able to enjoy the mystery and suspense of the films as intended, with no foreknowledge of their outcome or the identity of the killer, but reading the books after the fact has the pleasant effect of filling in some of the narrative blanks and

backstory impossible to include in a film.

What I liked so much about the film version of Murder

on the Orient Express is that in addition to a crackling murder mystery, it offered, by way of subtext, a poignant illustration of the manner in which a single act of

violence can have a rippling effect resulting in the harm done to one ultimately wounding a great many others. The film version of Death on the Nile I’ve always felt

suffered from being too much of a tale told expediently. It’s a great mystery with

interesting characters and many surprises, but I never felt it had anything larger to express. Certainly, nothing to justify that aforementioned choke in

Poirot’s throat at the end of the film.

|

| Poirot and Colonel Race call the attention of the ship's manager (I.S. Johar) to a matter not at all pleasant |

And while I feel fairly safe in stating that little to none of these themes factor in John Guillermin's film adaptation, keeping it in the back of my mind as I rewatched Death on the Nile did wonders for my reappraisal of it.

Clip from "Death on the Nile" (1978)

BONUS MATERIAL

Because so many fans of Death on the Nile have expressed feeling shortchanged by Simon MacCorkindale remaining fully-clothed throughout, by way of compensation I offer this screencap of Mr. Mac from the 1987 straight-to-video film: Shades of Love: Sincerely, Violet. A least that director knew man cannot live by Sphinx alone.

Because so many fans of Death on the Nile have expressed feeling shortchanged by Simon MacCorkindale remaining fully-clothed throughout, by way of compensation I offer this screencap of Mr. Mac from the 1987 straight-to-video film: Shades of Love: Sincerely, Violet. A least that director knew man cannot live by Sphinx alone.

|

| Simon Says: Eat your heart out |

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 -2015