Warning: Spoiler Alert. This is a critical essay, not a review. Therefore, many crucial

plot points are revealed and referenced for the purpose of analysis.

It’s Déjà vu All Over Again

I'm not sure which is worse: being a living, still-active film director and having to endure reading about every film school upstart and wannabe hailed as the "new" you, "next" you, or heir apparent to your throne—or being a young filmmaker striving to make your mark, only to have your work evaluated exclusively in terms of homage, pastiche, tip-of-the-hat to, or outright rip-off of an artist you admire.

For as long as I can remember, from Henri-Georges Clouzot (Diabolique) to William Castle (almost

everything he's ever done), Alfred Hitchcock has been the go-to comparison name for directors working in the suspense thriller genre. Director Brian De

Palma, from the days of his breakout 1972 feature Sisters (whose poster prominently featured the Hollywood Reporter quote: "The

most genuinely frightening film since Hitchcock's Psycho!"), has been

saddled with—and openly courted—comparisons to Hitchcock.

In our label-centric, brand-driven culture, this certainly makes

it easier for critics and studio marketing departments to pigeonhole artists and brand them with an identity to sell. But for film fans, it can feel like having to settle for a tribute

band after the genuine article has cut back on touring. You may enjoy how much

the tribute band sounds like the original and the way they evoke fond memories, but no matter

how good they are, they're an imitation. Plus, in focusing so much on how

successfully the tribute band has approximated the sound, feel, and experience of

the real deal, you never give yourself a chance to appreciate how talented the tribute band is (or

isn't) in its own right. Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, but making do with a copy can sometimes feel like an act

of willful self-deception.

As it just so happens, willful self-deception describes both the theme of Brian De

Palma's Vertigo-inspired film Obsession and my own personal viewing experience.

|

| Cliff Robertson as Michael Courtland |

|

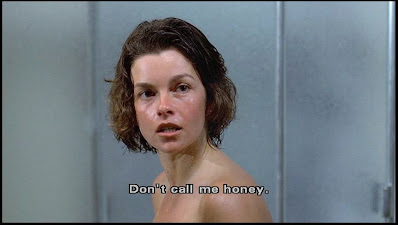

| Genevieve Bujold as Elizabeth Courtland/Sandra Portinari |

|

| John Lithgow as Robert Lasalle |

Following on the heels of the sleeper success of Sisters (which openly culled from Psycho, Rear Window, and featured a score by Hitchcock-associated composer Bernard Herrmann) and the undeserved flop of 1974's Phantom of the Paradise (a De Palma departure from type that seized upon the glam-rock zeitgeist mined in 1973's The Rocky Horror Show), the comparatively high-profile Obsession gave Brian De Palma his first mainstream commercial success.

A modest success, to be sure, but in grossing

$4.47 million on its $1.2 million budget, Obsession was a surprise hit. A hit that flew in the face of Columbia Studio's over-cautious distribution strategy that saw Obsession--after having sat on the shelf for almost a year--tentatively released with an indifferent ad campaign during the

"dog days" of August.

Alas, before Obsession had the chance to build up much steam or word-of-mouth, Carrie, De Palma's second 1976 release, opened in November, its overwhelming

critical and boxoffice success (the film grossed $15.2 million against a $1.8

million budget) fairly obliterating Obsession

from theater screens, and, until very recently, a great many people's minds, as

well.

|

| Florence, Italy 1948 |

Written by Paul Schrader (Taxi Driver), the screenplay is based on a story by Brian De Palma, inspired by their experience at an L.A. County Museum screening of the then long-out-of-circulation Hitchcock classic Vertigo. Obsession is a romantic thriller about love, loss, grief, guilt, deception, and emotional fixation. Pretty much everything you've come to know and expect from Hitchcock and those who seek to sincerely flatter the Master of Suspense through imitation.

But while Paul Schrader's derivative screenplay borrows copiously from Hitchcock, calling Obsession

a romantic "thriller" (the film was promoted with the tagline: "The love story that will scare the life out

of you") would be a bit of a stretch. Inarguably romantic in theme

and possessed of several intense moments of emotional conflict, anyone coming to Obsession expecting the kind of excesses of violence associated with De Palma after Dressed to Kill or Scarface would do well to be reminded that Obsession is rated PG, and its thrills (mercifully) are on the restrained side. So, if I'd have to label it at all (oh, and I do), I'd call Obsession a romantic suspense film or romantic mystery.

The time is 1959. Michael Courtland (Robertson) is a successful New Orleans real estate developer whose beloved wife Elizabeth (Bujold) and 9-year-old daughter Amy (Wanda Blackman) are kidnapped. A botched effort to capture the kidnappers without paying the ransom results in the violent deaths of both wife and child, a tragedy for which Courtland blames himself and is haunted by for years.

A great many of Brian De Palma's by-now

trademark stylistic flourishes are in full evidence throughout Obsession. His familiar

swirling camera effect is put to particularly effective use in a 360°

pan that takes Michael Courtland from grieving widower

in 1959 (top) to morose obsessive in 1975.

A broken man consumed with guilt over the role he perceives himself

to have played in his family's death, Michael is stuck in 1959 and unable to

move on with his life. Even going so far as to thwart the desires of friend

and junior business partner Robert Lasalle (Lithgow) by allowing a prime piece

of valuable New Orleans real estate to lie undeveloped for the sole purpose of

erecting a doleful monument to his wife and child on the site.

In an effort to dislodge Michael from his crippling depression, Lasalle persuades

Michael to accompany him on one of his frequent business trips to Florence,

Italy. It's there that Michael, while sentimentally and morbidly visiting the church

where he and his wife met in 1948, catches sight of an art restorer who (wouldn't you know it) happens to be a dead ringer for Elizabeth.

Upon being reassured by Lasalle that the Italian-style doppelganger was no mere hallucination or trick of the brain, Michael, thrown into a tailspin

by the uncanny coincidence of locale and resemblance, becomes consumed with the

idea that fate has offered him both a second chance at love and a stab at redemption.

Embarking on a whirlwind course of seduction consisting of stalking, persistent courting, and matrimonial proposal, Michael, in due course, whisks Sandra back to his New Orleans home, where whatever remaining line between fantasy and reality can only become even more blurred. And it does.

While awaiting their

rushed wedding day, Michael, happy at last, exhibits a marked improvement in disposition

and demeanor that his friends and associates interpret (with good reason) as

his becoming more detached from reality by the day. Meanwhile, Sandra--ensconced

in his shrine-like home and left on her own to study Elizabeth's old photos and

diaries for hours upon end--cultivates an obsession of her own. She becomes

so immersed in the past life of the dead woman that she begins progressively making herself over in Elizabeth's image.

Love and desire figure into all this somewhere, but it takes

a backseat to the morbidity of Michael and Sandra's escalating Folie a Deux: a double-fantasy/shared-delusion speeding

headlong on a collision course toward an inevitable, preordained destination...the reenactment and hoped-for reversal of that fateful night that changed Michael's

life forever. But can one really repeat the past? And if so, how wise is

it to do so?

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT

THIS FILM

I'm not sure if you can make a really riveting film about obsessive

love if you approach the material academically. I have no idea what Schrader

and De Palma had in mind after they watched Vertigo

and struck on the idea to collaborate on a film, but I would hope that each had

something particular and personal to say on the topic of love unending that

turns into an all-consuming fixation. Not having read the entire original

screenplay (said

to have included a whole third act, which was jettisoned before filming began),

I can only say that the finished movie plays out like the most expensive film

school thesis project ever made.

Mind you, I say that not as a put-down, but from the impression I got that Obsession came out of Schrader and De Palma being impressed with Vertigo from an intellectual perspective, not an emotional one. They clearly wanted to try their hand at a similar style of film, but forgot to add either intensity or urgency. I can't help but admire their success in achieving their academic goal, for Obsession is a fine, handsomely mounted romantic

mystery that does all that I believe it sets out to do. From a filmmaker's

perspective, that is. From the perspective of a guy sitting in the audience waiting to be swept up in madness by proxy, Obsession is what I might call a Transfusion Film: it has no blood of its own.

Obsession has all

the technical and stylistic pluses of Vertigo,

but it lacks the crazy. Michael and Sandra are characters caught up in something neurotic and deeply rooted in pain, but the film kept me at an emotional remove. I don't feel it. I didn't feel any of the eerie undercurrents one would expect from a story this unusual.

Vertigo, for all its late-1950s restraint, is one weird movie. There's a creep-out factor in Jimmy Stewart's portrayal of Scottie's character, which informs his actions. An actor I've never felt comfortable admitting I've never warmed up to (I mean, who doesn't like Jimmy Stewart?), to me, Stewart has always come across as disturbed and creepy, even when he's supposed to be charming and relatable.

Vertigo, for all its late-1950s restraint, is one weird movie. There's a creep-out factor in Jimmy Stewart's portrayal of Scottie's character, which informs his actions. An actor I've never felt comfortable admitting I've never warmed up to (I mean, who doesn't like Jimmy Stewart?), to me, Stewart has always come across as disturbed and creepy, even when he's supposed to be charming and relatable.

But Vertigo chiefly benefits from Hitchcock's personal demons and

obsessions seeping through the edges of every frame. Hitchcock himself doesn't seem to be aware of it, but by his very treatment of the material, he keeps providing inadvertent peeks into the darkest corners of his own psyche. All of this gives Vertigo that quirky, kinky kick that didn't exactly sit well with audiences in 1958.

Conversely, Obsession is a meticulously-crafted genre film that manages to hit all the right stylistic marks, but comes up short by lacking the requisite feverishness of its overheated premise. Robertson's Michael Courtland looks tortured and haunted, but he never seems capable of losing control. Perhaps this is due to the discarded

third act, which begins where the current film ends and would have placed the

characters in 1985, involving them in a third episode of obsession. Or maybe it's

the studio's insistence that the unappetizing incest subtext be removed and

reworked through editing (a pivotal scene that was to occur in real life between the characters has been changed into a dream sequence). Whatever the source, there's a big

hole at the center of the rather sumptuous package that is Obsession, and it feels like the film functionally sidesteps touching on any aspect of Courtland's passion that intersects with perversion.

In this, the first of three films he would make with De Palma, John Lithgow plays a character described in the script as "The slightly souring cream of the old south." I mention this because, without that knowledge, Lithgow's performance comes off as a tad overripe. Southern accents have to be pretty solid not to sound like dinner theater Tennessee Williams, and if Lithgow's doesn't exactly convince, its inauthenticity fits the potential duplicity of his character. Also not helping matters much is that he's also saddled with an absolutely terrible fake mustache (at least, I hope it's fake) and an arsenal of cream-colored suits that look like they come from The Rex Reed's Collection. That all of these potential drawbacks more or less work in Lithgow's favor has as much to do with the actor's talent as it does with his character needing to come off as both smarmy and charming in equal measure.

The ending is a suspenseful, startling, and very moving bit of pure cinema. Pure cinema because it is gratifying in ways that have nothing to do with narrative logic or reason, but everything to do with the overwhelming power of the mechanics of style. The sequence works simply because it visually fulfills, in those final minutes, all the romance, passion, and mystery its premise had always promised. Perhaps it's an example of too little too late, but it's only during the film's final scenes that Obsession finds its "crazy." And when it does, it's simply beautiful. Too bad that crazy passion took so long to rear its head.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2017

|

| Sandra visits Elizabeth's grave |

PERFORMANCES

Brian De Palma had this to say about making Obsession in the 2015 documentary De Palma: "I think the weakness of the movie is Cliff, and the greatness is Geneviève. I mean, she carries the movie."

Citing Robertson's awareness that Bujold was taking over the film, De Palma states that Robertson resorted to tricks intended to sabotage her performance and that, overall, he found Cliff extremely difficult to work with. Clearly having an ax to grind, De Palma goes on to relate an anecdote

conveying his frustration over Robertson -- playing a man who is supposed to look drawn

and pale from having locked himself away out of grief -- insisting on

applying coats of bronzer to his face. So much so that the cinematographer one day forcibly

placed Robertson against the mahogany set, shouting, "You're the same color as this wall! How am I supposed to light you?"

While I don't share De Palma's opinion that Robertson is the weakness of the film (he hasn't much range, but his Michael Courtland is rather heartbreaking), I wholeheartedly agree that without Bujold, I'm not at all certain Obsession would have worked for me at all. A longtime favorite, she is an endlessly resourceful actress of intensity, authenticity, and complexity. An intelligent, natural actress like Bujold doesn't have the ethereal vulnerability of Kim Novak, but what she brings to the table is an emotional verisimilitude that does wonders for making the implausible feel real. And in this film, this quality alone is worth a king's ransom. Bujold (as always) is a stunner and gives Obsession its mystery and, ultimately, its poignancy. |

| Bujold seemed to be everywhere in 1976. Obsession was released almost simultaneously with her films Alex and The Gypsy, and Swashbuckler. |

In this, the first of three films he would make with De Palma, John Lithgow plays a character described in the script as "The slightly souring cream of the old south." I mention this because, without that knowledge, Lithgow's performance comes off as a tad overripe. Southern accents have to be pretty solid not to sound like dinner theater Tennessee Williams, and if Lithgow's doesn't exactly convince, its inauthenticity fits the potential duplicity of his character. Also not helping matters much is that he's also saddled with an absolutely terrible fake mustache (at least, I hope it's fake) and an arsenal of cream-colored suits that look like they come from The Rex Reed's Collection. That all of these potential drawbacks more or less work in Lithgow's favor has as much to do with the actor's talent as it does with his character needing to come off as both smarmy and charming in equal measure.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Without a doubt, the most persuasive obsession on display throughout Obsession is

Brian De Palma's love of film and reverence for Hitchcock. When it comes to the

De Palma arsenal of visual tricks (split screen, swirling camera, weird angles,

deep focus through the use of split diopters…), I honestly don't know which are

genuinely his or which are attributed to Hitchcock's traditional style. In essence, it shouldn't really matter, but the problem presented by the rash of young 1970s directors who built their careers on paying homage to the films they grew up on is that they invite you to pay attention to such things.

|

| Making A Spectacle The thick glasses worn by Courtland's therapist (Stocker Fontelieu) in Obsession recall Kasey Rogers' pivotal eyewear from Hitchcock's Strangers on a Train |

When, under normal circumstances, all I want to do is sit

back and enjoy a film on its own merits, this league of self-conscious, self-aware,

and self-referential filmmakers (Peter Bogdanovich comes to mind) invites me to

participate in an insider's game. One side of my brain is supposed to watch the

film as a straightforward narrative, while simultaneously, the other side of my brain is

induced to play "catch the reference."

Keeping track of all the cinematic references, comparisons, re-creations,

and outright thefts can be a lot of fun for a film geek like me, but it comes at a

price: all that attention to style keeps me at an emotional remove from the story being told. Each visual nod to a well-known film, each insider homage to a beloved filmmaker's technique calls attention to itself and serves as a tap on the shoulder, reminding me that I'm watching a movie.

I watch the

film, even enjoy the film, but since the filmmaker is "toying" with the cinema technique...I never surrender to it.

|

| Scissors figure prominently both in Obsession and Hitchcock's Dial M for Murder |

Obsession is a

film bursting at the seams with style. It looks great: Oscar-winning

cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (Close

Encounters of the Third Kind) bathes the film in a dreamy, diffused-lit

glow that creates an appropriately unreal reality. And it also sounds great: This is perhaps my favorite Bernard Herrmann score.

But for all the engaging performances and cinema

storytelling savvy, for the life of me, I can't say the film ever swept me up in

the obsessions that are the key to making the film really work. There's a lot going on that keeps you in your seat and keeps you wondering (and even caring) what will happen next, but a film like Obsession should be haunting.

Once the film is over, there should be something about this eerie narrative that is difficult to shake off. Personally, I think if half the care lavished on the look and atmosphere of the film had been applied to the characters and performances, Obsession would have been the De Palma film you couldn't forget instead of the De Palma film almost no one remembers.

|

| The Vertiginous Circle The camera swirling around two individuals locked inside their own world is easily my favorite effect |

In writing about the Hitchcock style that runs throughout Obsession, I suppose it's worth noting that in 1976, Alfred Hitchcock released his 53rd (and final) feature film, Family Plot. It opened in theaters four months before Obsession was released (and perhaps played a role in the shelved Obsession finally getting a release date).

I don't recall if critics made any comparisons between who was more Hitchcockian at this point: the pretender or the real deal; but I do remember that so much nostalgia was attached to the release of Family Plot (Hitchcock was 77 and ailing) that few dared hint that the Master of Suspense's latest effort was not really all that memorable, either.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

There's an old axiom in film that goes something like: They'll forgive you anything if you have a good ending. Screenwriter Paul Schrader has been on the outs with Brian De Palma ever since (under the insistence of Bernard Herrmann) he dropped Deja Vu's third act. I've no idea how the original ends (the uncut screenplay is featured with the UK DVD version of Obsession), but for my money, the ending as it stands is sheer perfection.

Many a good thriller finds itself fizzling out to a so-so or anticlimactic conclusion after a promising buildup. Obsession is the exception. Starting with a great, albeit familiar, premise, the film builds methodically and atmospherically throughout, even managing to sustain suspense as the key to the relatively easy-to-figure-out mystery reveals itself.

Late in the film, things grow worrisome as it appears as though Obsession's measured pacing is to be abandoned in favor of a hasty denouement; but De Palma has one more trick up his sleeve and it proves to be so good that you honestly do forgive the film its implausibilities (big and small) and its short-shifting of character and motivation.

There's an old axiom in film that goes something like: They'll forgive you anything if you have a good ending. Screenwriter Paul Schrader has been on the outs with Brian De Palma ever since (under the insistence of Bernard Herrmann) he dropped Deja Vu's third act. I've no idea how the original ends (the uncut screenplay is featured with the UK DVD version of Obsession), but for my money, the ending as it stands is sheer perfection.

Many a good thriller finds itself fizzling out to a so-so or anticlimactic conclusion after a promising buildup. Obsession is the exception. Starting with a great, albeit familiar, premise, the film builds methodically and atmospherically throughout, even managing to sustain suspense as the key to the relatively easy-to-figure-out mystery reveals itself.

Late in the film, things grow worrisome as it appears as though Obsession's measured pacing is to be abandoned in favor of a hasty denouement; but De Palma has one more trick up his sleeve and it proves to be so good that you honestly do forgive the film its implausibilities (big and small) and its short-shifting of character and motivation.

The ending is a suspenseful, startling, and very moving bit of pure cinema. Pure cinema because it is gratifying in ways that have nothing to do with narrative logic or reason, but everything to do with the overwhelming power of the mechanics of style. The sequence works simply because it visually fulfills, in those final minutes, all the romance, passion, and mystery its premise had always promised. Perhaps it's an example of too little too late, but it's only during the film's final scenes that Obsession finds its "crazy." And when it does, it's simply beautiful. Too bad that crazy passion took so long to rear its head.

|

| Past or Present? / Original or Copy? |

BONUS MATERIAL

Scene from Brian De Palma's "Obsession" 1976

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)