|

| Middle Man |

I mention this because, when it comes to movies, I tend to forget that around this same time (roughly 1967 - 1978), Hollywood was in the midst of its own revolution, dubbed the New Hollywood. A revolution the floundering studios responded to with its own brand of MOR counterprogramming designed to satisfy the needs of the middle-age-bracket ticket-buyer who still saw movies as primarily a "family medium" and went to theaters for escapism, not significance.

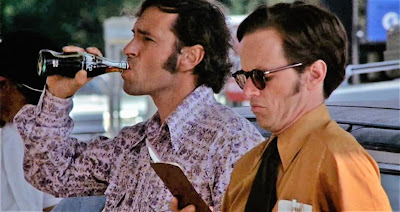

In the years following the breakout success of Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Easy Rider (1969), a struggling film industry began aggressively courting the rapidly-growing youth market. Embracing unconventional films with topical themes, profanity, and graphic displays of sex, nudity, and violence. The goal was to attract audiences by offering them what they couldn't get on television. While Hollywood traditionalists balked at the newfound climate of permissiveness, the college-age demographic seized the marketplace. It was the disposable income of the young that turned offbeat, taboo-shattering films like Midnight Cowboy (1969), A Clockwork Orange (1971), and Last Tango in Paris (1972) into major boxoffice hits.

Meanwhile, television remained the dominant entertainment choice for the dwindling 35 to 64-year-old market. But, when given the right G or GP-rated inducement, they proved their age bracket was still capable of showing up in significant enough numbers to make such old-fashioned (if not downright primordial) movies as Yours, Mine, & Ours (1968), The Love Bug (1969), and Airport (1970) some of the highest-grossing films of their respective years.

|

| Stuck in the Middle with You |

The "Hollywood Renaissance" era of the '70s is rightfully remembered for its creative daring and for producing groundbreaking films like The Graduate (1967), Klute (1971), and MASH (1970). But they are also the years when doggedly routine MOR comedies sought to straddle the fence through stories that looked at the rapidly changing cultural landscape through a reactive, decidedly middle-aged (primarily male, always white) prism.

The undisputed master of MOR movies at this time was the late Neil Simon. He built an entire career out of glorifying the middle-aged, middle-class everyman who's bewildered by a world that is changing too fast. Having begun his career writing for early TV (Your Show of Shows, The Phil Silvers Show), the prolific playwright, screenwriter, and Broadway golden boy was a master of sitcom plotting and gag-heavy humor. All of which reassured ticket buyers that a night out with a Neil Simon movie was a guaranteed risk-free, comfortingly familiar experience. Dubbed the "King of Kvetch Comedy" for almost a decade, Neil Simon had his finger on the arrhythmic pulse of America's "middlers"— folks too old for the Pepsi Generation but not yet ready to join the Geritol set.

|

| Barney's Queen of the Sea Sweet, savory salmon saute swimming in salivary succulence |

But by 1972, when even TV sitcoms were beginning to adopt a hipper, more contemporary comedy style (The Mary Tyler Moore Show, All in the Family, and Maude all premiered between 1970 and 1972) and Simon--who turned 45 that year, the same age as the main character in Last of the Red Hot Lovers--found that his trademark jokey, setup-payoff style had begun to feel dated even to his core audience. Which perhaps explains why the audience that had helped turn his early screen adaptations Barefoot in the Park (1967) and The Odd Couple (1968) into boxoffice hits went largely MIA by the time Star Spangled Girl (1971) and Last of the Red Hot Lovers (1972) came out.

|

| Alan Arkin as Barney Cashman |

|

| Paula Prentiss as Bobbi Michele |

|

| Renee Taylor as Jeanette Fisher |

If Classical Hollywood's fumbling efforts to join the New Hollywood youthquake were a movie, that movie would be Neil Simon's Last of the Red Hot Lovers. It's the story of Barney Cashman. Balding, happily married, settled-in-his-ways, Barney Cashman, who wears a blue suit every day when he drives his black 4-door sedan from Great Neck to New York to open his seafood restaurant. The routine sameness of Barney's life has him, at age 45, both contemplating his mortality and grappling with the nagging certainty that on the battlefront of the '70s Sexual Revolution, God has classified him 4-F.

It's Barney's deepest desire to have just one afternoon of "exciting" in a life that has thus far been one uninterrupted stream of "nice." Neil Simon's midlife-crisis comedy of bourgeois manners chronicles Barney's earnest but disastrous pursuit of the perfect Afternoon Delight.

|

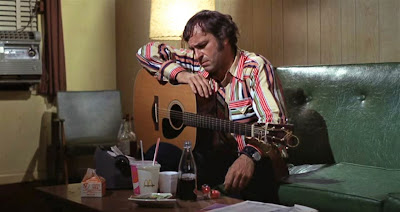

| The Peacock Revolution Along with everything else, men's fashion underwent an upheaval in the '70s. Bold styling and vivid colors signified youth and sex appeal |

Although a Tony Award-nominated hit when it opened on Broadway in 1969 (with James Coco in the lead), Last of the Red Hot Lovers —the 7th of Simon's plays to make it to the screen—hit theaters during a downtrend in Simon's career and, like Star Spangled Girl before it, opened to terrible reviews and non-existent business. By the time it was released on VHS in the early '80s (when I saw it), it had earned the reputation of being the most missable of Simon's screen adaptations.

So wouldn't you know it...coming to Last of the Red Hot Lovers with rock-bottom expectations and the participation of faves Paula Prentiss and Sally Kellerman as my sole interest, I wound up laughing louder, longer, and more frequently at LOTRHL than any other Neil Simon film I'd seen to date. That was more than 40 years ago. Today, even after multiple revisits, Last of the Red Hot Lovers still remains my #1 favorite Neil Simon stage-to-screen adaptation.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

The obvious reason I love Last of the Red Hot Lovers is that it makes me laugh. A lot. What's not so obvious is why. It's not like I'm blind to the film's numerous shortcomings: Neal Hefti's oddly dispiriting musical score; director Gene Saks' (Mame) pedestrian approach to the material (it looks like a TV movie that ran into budget trouble); and the overall sense that the film's premise is too thin to support the level of repetition imposed upon it by its "comic triple" structure.

For those unfamiliar, the Comic Triple is the ages-old comedy writing principle that says things are funnier in threes. A setup built around - 1. normal, 2. normal, 3. surprise!

A typical example is this exchange from Young Frankenstein (1974)-co-written by Gene Wilder and Mel Brooks:

1. "Would the doctor care for a brandy before retiring?"

- "No. Thank you."

2. "Some warm milk, perhaps?"

- "No. Thank you very much. No, thanks."

3. "Ovaltine?"

Like Simon's earlier play, Plaza Suite, Last of the Red Hot Lovers has a "3-in-One" structure (three one-act playlets united by the same male lead) that turns the film itself into a Comic Triple. But 98 minutes was an awfully long time to wait for a punchline for some.

(Mel Brooks and Neil Simon were friends who both started as writers for Your Show of Shows in the '50s. Only a year apart in age, Simon never really shed his status as the comic darling of the blue-hair set, but Mel Brooks' broad farces and satirical movie homages struck a chord with young audiences and came to influentially exemplify the look of hip, college-crowd comedy in the '70s.)

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

In Last of the Red Hot Lovers, Barney Cashman's failed trio of trysts in the New York apartment of his 73-year-old mother (empty two days a week from 3 to 5 when she's out doing volunteer work at Mount Sinai) begins in the winter of his discontent and continues through summer and fall. Making him a sort of frustrated man for all seasons. Each encounter brings about subtle changes in Barney, which should have a unifying effect and make the film feel more like a single narrative. Alas, the variance in tone and pacing of these sequences felt less like watching a movie with a cohesive plotline and more like watching the isolated sequences in an episode of Love, American Style.

LOVE AND THE SENSUOUS WOMAN

|

| "I get cravings. To eat, to touch, to smell, to see, to do. A physical, sensual pleasure that can only be satisfied at that particular moment." |

The first sequence is the most quintessentially Simonesque of all the episodes. A machine-gun barrage of wisecracks and one-liners delivered with surprising comic panache by an amusingly salty Sally Kellerman with a prototypically subdued Alan Arkin – the master of comic stillness – playing straight man. The occasion of two married people agreeing to meet for an afternoon of no-strings adultery has Simon applying his The Odd Couple formula of close-quarters dissimilarity-conflict to an unforeseen obstacle: anxious Barney is looking for romance while illusion-free Elaine ("A coughing woman of Polish persuasion") is looking for sex.

What should be a semantic non-issue becomes a Wall of Jericho as Barney's stubborn need to justify his infidelity with sentimentality finds no common ground with Elaine's clear-eyed sexual pragmatism. Behind the witty barbs and comebacks in their talking-in-circles banter lies a sharp discourse about the death of romance in the age of Deep Throat and Portnoy's Complaint (two films that came out the same summer as Last of the Red Hot Lovers).

In her 2013 memoir, Sally Kellerman cited her performance in Last of the Red Hot Lovers as her proudest career accomplishment, which I'm in absolute agreement with. Reminding me of one of those silent wives in a Martin Scorsese mob movie, Kellerman's hard-edged Elaine Navazio is a standout and my favorite performance of her career. The writing in this sequence is perhaps the tightest and funniest, and Kellerman has a great comedy rhythm with Arkin (the two would team again in 1975's Rafferty and the Gold Dust Twins).

What hasn't been as obvious to me until multiple revisits is how hilariously in character Arkin's underplaying is. His performance is infused with dozens of small bits of business (the running gag of his non-drinker's reaction to drinking, for example) that not only set up and support Kellerman's jokes beautifully, but nicely establish many of Barney's behavioral details that pay off in latter sequences to illustrate his evolution as a red-hot lover.

LOVE AND THE ACTRESS

.jpg) |

| "I don't need their stinkin' show. I'm more of a movie personality. Barbra Streisand, Ali MacGraw... that's the type I am." |

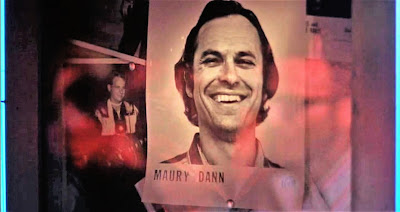

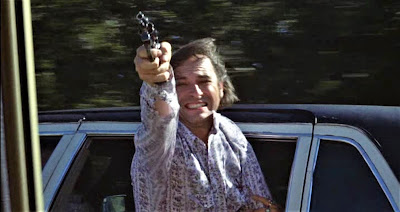

The first playlet ended with Barney emphatically vowing, "I will never, never, never do that again." In this chapter, which stands as the requisite "silly" episode in Neil Simon's 3-act formula (remember that passed-out hooker storyline in California Suite?), we learn that "never' for Barney is about six months. It's summer, and having shed his romantic illusions along with his winter suit, Barney is again inspired to entertain a young woman in his mother's apartment. This time it's Bobbi Michele (Prentiss), the "theatrically built" actress-singer he meets in the park.

From Barney's outside-looking-in perspective on the sexual revolution, Bobbi represents all those beautiful, long-legged, mini-skirted, sexually uninhibited women Barney sees and fantasizes about on the streets and staring out at him from the covers of sexy magazines. That she turns out to be Grade-A Looney Tunes turns their afternoon into a "be careful what you wish for" male midlife-crisis cautionary tale.

From Barney's outside-looking-in perspective on the sexual revolution, Bobbi represents all those beautiful, long-legged, mini-skirted, sexually uninhibited women Barney sees and fantasizes about on the streets and staring out at him from the covers of sexy magazines. That she turns out to be Grade-A Looney Tunes turns their afternoon into a "be careful what you wish for" male midlife-crisis cautionary tale.

I'm a huge admirer of the woefully underappreciated Paula Prentiss, so I feign no objectivity when I say she's hysterically funny in this essentially made-to-order role. Not a popular performance even among many of her fans, but I find her brilliant. No one does kooky-sexy like Prentiss; her distinctive delivery and impeccable timing work to make the comedy in this sequence feel almost absurdist.

LOVE AND THE TIMES WE LIVE IN

|

| Jeanette - "You're not appalled by the times that we live in? The promiscuity you find everywhere?" Barney - "I haven't found it anywhere! I hear a lot about it, but I haven't found it!" |

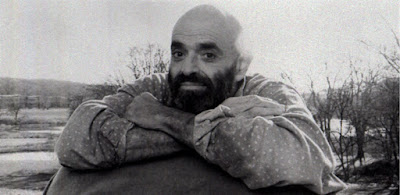

Last of the Red Hot Lovers gets a bit serious in this final installment. A family friend whose husband is having an affair (Taylor) plummets into a deep depression and solicits the by-now practically predatory Barney for an ill-advised revenge dalliance. In the course of trying to seduce the woman after she's already expressed she's having second thoughts, Barney has a Willy Loman moment where he's confronted with his moral hypocrisy and the very real possibility that he may not be the decent man he prides himself on being. Amidst this, the film seems to make the questionable (but no doubt comforting) leap that before the sexual revolution introduced so many gray areas, America was a bastion of heterosexual monogamy. Conveniently ignoring the decades of smutty sex comedies (some written by Simon himself) satirizing the morality of suburban bed-hopping.

In later years, Neil Simon would improve at balancing comedy-drama. But this third-act episode, which has Simon's characters dealing with some pretty hard-hitting truths, is written to be the broadest, most farcical sequence of them all.

Perhaps on stage, it came off better. But with the intimacy of the movie screen, the skill of Renee Taylor's performance only emphasizes the sequence's whiplash shifts in tone. (Taylor is superb. How she manages to be screamingly funny one minute and heart-breakingly real the next is remarkable.) Does it make me laugh? Yes. Between the running gags of Jeanette's handbag and her retreats to the coffee shop, it has me in stitches. Does it work? Intermittently, I'd say.

Once again, I call attention to how good Alan Arkin is, and in this sequence, he has to work with coming off as kind of creepy and unsympathetic. But both actors redeem the material's shortcomings through the authenticity of their characterizations.

.JPG) |

| Looking like Boris Badenov in the flesh, incognito Barney tries to make it to his mother's apartment unnoticed |

As a journalist noted at the time, Last of the Red Hot Lovers is a sad comedy about a genuine cultural phenomenon of the time: the youthquake era was the first time adults didn't look to their elders for guidance on how to live their lives, they looked to the young.

It's hard to know what being middle-aged must have felt like at a time when so much of life around you seemed to be in flux for only the young, but everyone can relate to feeling left out, feeling as though you're missing out, or that the parade is passing by. With Last of the Red Hot Lovers, Neil Simon takes a witty and insightful stab at exploring the experience of a character who had to go too far to learn that being in the middle wasn't so bad.

Clip from "Last of the Red Hot Lovers" 1972

BONUS MATERIAL

|

| Iconic Looks - The Lynx Fur Coat |

I really love the look of Sally Kellerman's Elaine in Last of the Red Hot Lovers. Especially her enormous fur coat. As character-defining costuming goes, the lynx fur coat worked overtime in the '60s and '70s. I don't know if they ever went through a phase when they were considered sincerely chic or glamorous. But whenever a character is sporting one in a movie, it always seems to serve as a signifier of a certain kind of brassy, East Coast vulgarity. Living in California, I don't think I've ever seen one in person, but my first screen lynx sighting was in 1967's Wait Until Dark when it was worn by street-savvy heroin smuggler Samantha Jones (bottom). Next, in 1970s The Owl and the Pussycat, Barbra Streisand's model/actress wore her omnipresent faux fur coat like it was sex-worker armor.

|

| Sally Kellerman (June 2, 1937 - February 24, 2022) |

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2022

.JPG)

.png)