One of my favorite Maya Angelou

quotes (one which paraphrases an earlier quote by Carl Buehner) is: "People will forget what you

said. People will forget what you did. But people will never forget how you

made them feel." I like this

quote because not only have I found it to be true in my life, but it also

summarizes what I've always maintained to be my own experience of film: I'll

forget what a movie made at the boxoffice. I'll forget whether critics deemed it

a hit or a flop. I'll forget if it won any Oscars. But I never forget how a

movie made me feel.

A great many things go into making

a motion picture: acting, direction, screenwriting, cinematography, mise-en-scène,

etc....simply a host of creative and aesthetic contributions by artisans

and craftspeople in collaboration. But I always contend that unless you're

discussing measurable, fact-based elements such as whether or not a scene is in

focus, or if a boom mike popped into frame; the act of ascribing value to a

film (to classify it as either a "good" or bad" movie) is not an act of objective appraisal, but an act

of subjective evaluation. In other words, to express an opinion based on individual interpretation, firsthand point-of-view, and personal

taste.

I love movies. I've loved movies for as long as I can

remember. I get a kick out of reading about them, discussing them, analyzing

them, and especially writing about them. But one of the risks of being a devoted

cinephile and immersing myself so (too?) deeply in film theory and fandom minutiae is that I can occasionally forget what made me fall in love with movies

in the first place: they're a great deal of fun.

Academic essays about films I chiefly respond to emotionally can be enlightening, often enriching my enjoyment by encouraging me to look beyond a movie's more accessible virtues. In such instances, I'm gratified to find both my heart and head affected by a film. But every now and then, I fall in love with a movie so voluptuously visual, so lyrical, so ardently impassioned in its sensibilities that I simply surrender myself entirely to its sensual charms and (for better or worse) wind up leaving my analytical brain at the door.

For me, Camelot is such a film.

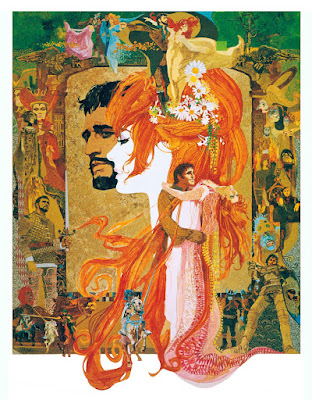

With Camelot's artwork staring out at me from the poster display case in front of the Coronet

Theater on Geary Street and from the cover of the

Columbia Record Club mail-order soundtrack LP that arrived at our door one day because

my mom forgot to send back the "not interested" card the month previous; suddenly

this stodgy, must-to-avoid, middle-aged entertainment became the movie I

couldn't wait to see.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Time has been kind to Camelot, which is ironic, since complaints about its abuse of time (even devoted fans tend to find it overlong) have dogged the film since its release. No longer denounced for being out of step with the changing tastes of the '60s, Camelot now belongs to the forgiving rear-view gaze of Classic Hollywood. The up-and-coming stars in its cast are now revered film industry veterans. The traditional style of filmmaking employed, one lambasted for being creakily old-fashioned during the youthquake '60s, is now revered for its scope and grandeur...all devoid of CGI enhancement. And its melodic score now hearkens back to an era when a timeless traditionalism defined what we came to know as musical theater.

Yet, Camelot remains unique in that it is one of those films whose dividing line of opinion never seems to shift. I've never known of anyone who hated the film to ever come around to a more favorable opinion over time, similarly, those who started out loving it (as I do) can't be talked down from our cloud no matter what detractors say.

I can't speak for everyone, but I guess back when I was 11-years-old, maybe I just took it to heart when Arthur said at the end of the film, "What we did will be remembered."

BONUS MATERIAL

King Arthur's Camelot took on the role of a Himalayan lamasery in the 1973 musical Lost Horizon

Camelot was revived on Broadway in 1980 with Richard Burton recreating his Tony Award-winning role as Arthur. When Burton succumbed to ill health in 1981, Hollywood's King Arthur—Richard Harris, then 51-years-old—stepped into the role. Harris would go on to purchase the rights to the stage production and toured with Camelot for six more years. This production, co-starring Meg Bussert as Guenevere and Richard Muenz as Lancelot, was broadcast on HBO in 1982 and is available on YouTube.

Richard Harris passed away in 2005, nearly as famous then as he was at the time of Camelot thanks to his role as Dumbledore, the Headmaster at Hogwarts in the first two Harry Potter films. But a real-life fairy tale romance played out for Vanessa Redgrave and Franco Nero who fell in love during the making of Camelot, had a child out of wedlock, made a couple of films together, separated in 1971, reconnected some thirty years later, and ultimately wed in 2006. In 2017, when she was 80 and he 75, they waltzed together on the Italian TV dance competition program Strictly Come Dancing.

Richard Harris had quite the recording career, releasing several albums throughout the '60s and '70s. His biggest success came with 1968's Grammy-nominated album A Tramp Shining, which featured the #2 Billboard hit, the talk-sing version of MacArthur Park. I never owned that now-rare curio, but a particular favorite I never tire of listening to is Harris' guest stint as "The Doctor" (talk-singing his way through Go To The Mirror with Steve Winwood and Roger Daltrey) on the 1972 studio recording of Tommy, The Who's double-LP collaboration with the London Symphony Orchestra and a host of guest artists.

For me, Camelot is such a film.

|

| Richard Harris as King Arthur |

|

| Vanessa Redgrave as Guenevere |

|

| Franco Nero as Lancelot Du Lac |

|

| David Hemmings as Mordred |

The mystical legend of King Arthur, Guenevere, Lancelot, and

the knights of the Round Table is tunefully romanticized in Camelot, Alan Jay Lerner's (lyricist &

librettist) and Frederick Loewe's (composer) follow-up to their wildly

successful My Fair Lady. I was but 3 years old when Camelot opened on Broadway in 1960 with a cast featuring Richard Burton, Julie Andrews, Robert Goulet, and Roddy McDowall. I was ten when Warner Bros. released its heavily publicized, three-hour,

70mm, $13-17 million (depending on the source) big-screen film version in

1967. In other words, as a child, I had no real memory of a world without Camelot in it.

|

| Lionel Jeffries as King Pellinore |

When I was very young, I linked Camelot to dull, suitable-for-parents-only entertainment,

associating it exclusively with Robert Goulet crooning the ballad "If Ever I

Would Leave You" on TV variety shows (as I had Barbra Streisand and the song

"People"). Following that, the show's title tune became married to sad memories

of President Kennedy's assassination after my teacher (per the 1963 Jackie

Kennedy Life magazine interview

wherein it was referenced as the late president's favorite song) played that paeanistic

anthem to our class, resulting in a roomful of first-graders bursting into tears

without any of us really knowing why. Not long after this, Camelot became familiar to me as an Original Broadway Cast album

that every parent seemed to have in their home, yet never played.

By 1967 my family had settled in San Francisco, and it's

then that I recall first catching sight of Bob Peak's colorfully alluring artwork

for the movie poster. Still one of my favorite movie posters, I responded strongly

to it because it resembled the then-popular psychedelic/Art Nouveau-style of

San Francisco rock and roll concert posters that I saw posted all over the

Haight/Ashbury district where we lived.

Of course, in the days when double and even triple features

were the norm, the idea of paying $3 or $4 (75¢ to $1.50 was average) to see just one

movie didn't sound all that appealing to my young mind. As it turns out, the idea sounded even less so to the more mature minds of my parents. Both of whom were of the opinion that taking me with them to see Camelot was- "Out of

the question. I'm not going to shell out that kind of money for the privilege of watching you

fall asleep!" That's what drive-ins were for.

So, until Camelot

became available at "popular prices" and made its way to our neighborhood

theater, I had to content myself with listening to the soundtrack album.

And listen to it, I did. Constantly. Persistently.

Rapturously.

I fell in love with the sound of Camelot before I ever saw a single frame.

I finally saw Camelot

sometime in late 1968; by then, the film's flop* status was common

knowledge, and some 30 minutes of footage from the roadshow version had been excised

in an effort to speed things along, so to speak.

*A huge bone of contention among retro film fans is the

word "flop" ascribed to a beloved favorite. Hollywood has long held to the

unwritten rule that a movie needs to make at least two to three times its

production costs to begin to show a profit. Thus, while Camelot saw out the year as #11 on the roster of top-grossing films of 1967 (meaning it was reasonably popular with the public), with its $15 million production

budget, a domestic boxoffice return of $31 million translates as genuine flop

material. The same holds true for many other "popular successes" that simply

cost too much to promote and distribute. One of the most notable is Hello, Dolly! which came in as the #4

top-grosser of 1969. But budgeted at a whopping $25 million and marketed to the

skies at a cost of at least half that amount, the $33 million it took in at the

boxoffice proved that it may have been popular with the public, but, from a financial standpoint, was nothing

short of ruinous for 20th Century-Fox.

Perhaps the most curious application of the word flop is

attributed to 1967's Valley of the Dolls.

Budgeted at a modest $4 million, VOD ranked #6 at the boxoffice and raked in an

astounding $44 million, making it a significantly profitable hit for the

studio. However, the film proved such a critical disaster and so devastating to

the careers of those involved, the label of "flop" has clung to it, largely in

reference to its quality (or lack thereof), not its profitability.

In any event, once the theater lights started to dim that

Saturday afternoon in 1968 (I can't remember whether it was at the Amazon or

the Castro theater), none of that made any difference, because no one else's

experience of Camelot mattered but my

own. I grew up with very little interest in most of the age-appropriate movies

of the time (I was an adult before I saw The

Sound of Music, Mary Poppins, or Doctor Dolittle), so at age eleven, I

hadn't had much exposure to fantasy or magic in movies. Camelot, which looked to me like a fairy tale come to life,

captivated my imagination from start to finish.

There in the dark, before this enormous screen, came a vision of opulent, extravagant fantasy that seemed to shimmer with an almost otherworldly luster. The scope, the color, the lush orchestrations, the pageantry…this creation of a world both magically artificial and hyperreal so overwhelmed my senses that I've no memory of what I actually thought of the story itself; only the sense memory of feeling totally and absolutely transported by a movie.

There in the dark, before this enormous screen, came a vision of opulent, extravagant fantasy that seemed to shimmer with an almost otherworldly luster. The scope, the color, the lush orchestrations, the pageantry…this creation of a world both magically artificial and hyperreal so overwhelmed my senses that I've no memory of what I actually thought of the story itself; only the sense memory of feeling totally and absolutely transported by a movie.

It was aesthetic overload. I was absolutely floored by how

gorgeous everything and everyone looked. Even those enormous, incessant, Panavision close-ups that drove so many critics to distraction were positively

swoon-inducing for me. All I knew was that, at the time, Camelot was

the most "movie" movie I'd ever seen.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT

THIS MOVIE

Clearly, most of what's recounted above is a young film fan's

response to the candy-store charms of old-fashioned Hollywood movie-making. Too

young to sense the dissonance so many found (and continue to find) in having a mystical,

musicalized wisp of romantic lore mounted as a massive, grandiose epic, I

simply fell under the spell of cinema's unique ability to give corporeal life to sublime fantasy.

Looking at Camelot

today (I watched it over the Christmas holidays) I'd like to report that my

adult self finds the film's pacing to be sluggish when it should be lilting;

the thin singing voices of the leads ill-serving of the score's lovely

melodies; the overall tone wavering unevenly between farce, romance, and drama;

the film's length interminable; the self-serious performances deadly to the

story's wit and humor; the sets artificial and stagey.

I'd like to, but I can't.

I acknowledge these things and recognize them to be sound and

justified criticisms leveled at the film by friends and loved ones (my partner,

a man of unyielding good taste and intelligence, cannot abide a single frame of

this movie); but they're flaws visible to me only when I look at Camelot through the eyes of others. When I look at Camelot

through my own two eyes, it's a little like the scene where Arthur, extolling

the virtues of Camelot to Guenevere, gives a brief lesson on how perspective

can change perception: "When I was young,

everything looked a little pink to me."

Because I can't separate the film from my experience of

first seeing it, Camelot still shines

with a kind of pinkish glow to me. I don't kid myself that Camelot is a better movie than it is, but my adult perspective—the

belief that one can derive perfect pleasure from an imperfect film—guides my youthful

perception of it as a magical, majestic, utterly charming musical...in spite of its flaws.

Due to having fallen in love with the music first, Lerner

& Loewe's magnificent score will always be my favorite thing about Camelot. Preferring the movie soundtrack

to the Broadway version (sorry, Julie Andrews), I adore the film's human-sized

interpretation of Arthur and Guenevere (Jenny, as he calls her) and never found

fault with the smaller, more emotive voices of Redgrave and Harris, which achieve

such a lovely, amatory quality in the duet "What Do the Simple Folk Do?" (my

absolute favorite song in the entire show). Perversely, perhaps, the one trained

voice in the film—that of singer Gene Marlino, dubbing

Nero's vocals—strikes me as hollow and generic in the dubbing style of Marni

Nixon and those disembodied, Doodletown Piper-style vocals they used in Hello, Dolly! and Lost

Horizon.

As big-budget musical epics go, Camelot, with its glorious Oscar-winning costumes and production

design, is nothing short of a dream; the film's vast scale is emblematic of Arthur's

full-to-bursting idealism. I suspect it was director Joshua Logan's intention

to use so many close-ups as a stylized means of creating emotional intimacy, but while this device is sensually effective in the romantic and dramatic scenes,

when the principals are required to break into song, it offers too many

opportunities to ponder the wonders of medieval dentistry.

PERFORMANCES

If you've ever seen an Arnold Schwarzenegger Conan the Barbarian movie or any of

those straight-to-DVD action films featuring the likes of Dolf Lundgren, one

can easily understand why mainstream superhero films have often found it more

advantageous to hire an actor and pad his suit (Michael Keaton, George

Clooney), rather than try to coax a performance and charisma out of an athlete or bodybuilder. I've always assumed a similar mindset

was behind the Hollywood custom of purchasing Broadway musical properties, and, instead of hiring individuals who can actually sing and dance, they engage the services of actors with minimal proficiency in either. Perhaps it's easier to teach an actor to sing

(dubbing!) than find song and dance entertainers who register effectively on the big screen.

I could devote an entire essay on both the soundness (Ethel

Merman, Carol Channing) and folly (Lee Marvin, Clint Eastwood) of this

practice; but confining myself exclusively to Camelot, I have to put forth that I find Vanessa Redgrave, Richard

Harris and Franco Nero all be exceptionally well-suited to their roles.

They are certainly the most visually stunning Arthur,

Guenevere, and Lancelot I've yet to come across (Nicholas Clay's virile Lancelot

in 1981's Excalibur being the

exception). Harris, a commanding and compassionate Arthur, Redgrave (Camelot's most valuable player) looking

like a fairy princess and bringing a touching wistfulness to her character; and Nero, abysmal lip-syncing aside, gives an engagingly robust,

sensitive performance.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

An unanticipated pleasure in having seen Camelot when it was first released, and then having the opportunity to revisit it some 50 years later, is to revel in the degree to which it embodies the attitudes

and trends of the past, while simultaneously commenting upon (with depressing acuity) our country's current "situation."

Camelot takes

place in a fictional kingdom in the Middle Ages, but (as was common of period films

in the days of the studio system) it has late-1960s written all over it. The

casting, opting for up-and-coming talent over established stars, reflects who was

hot at the time: Redgrave and Hemmings, fresh from cavorting nude in

Antonioni's Blow-Up; Harris recently

having bashed in Franco Nero's head in John Huston's 1966 film The Bible. The sound of Camelot

may be traditional Broadway, but its look is that of the world's most well-funded Renaissance

Pleasure Faire. This Camelot carries a decidedly flower-child, hippie-commune, love-in vibe.

Guenevere (with her mod bangs, cascading falls, and teased

hair bump…all color-coordinated with the castle and furnishings) is the world's

first flower-child; while Arthur—whose quixotic anti-war soliloquies sound like

a Berkeley campus lunch-hour messiah—sports a groovy pageboy haircut and adorns

himself with furs, capes, boots, and abundant eye shadow worthy of a Fillmore

rocker. Not to be outdone, the villainous Mordred struts about in a leather outfit that

looks to have been borrowed from Jim Morrison.

Alas, with Camelot's dark second half, quaint '60s nostalgia gives way to harsh contemporary relevance.

As Arthur's humane ideals crumble under his own hypocrisy (he decrees unpleasant facts he dislikes—talk of Guenevere's infidelity and Lancelot's betrayal—to be "fake news" and

banishes from the kingdom those who dare speak of what he actually knows to be true), Mordred, Arthur's vainglorious illegitimate son, tweets…I mean, boasts, "I've been taught to place needs ahead of conscience. Comfort ahead of

principle. I find charity offensive and kindness a trap," while making ready

his plot to Make England Uncivilized Again.

When Arthur laments, "Those

old uncivilized days come back again. Those days…those dreadful days we tried

to put asleep forever," he could be speaking of a dark day in Charlottesville,

Ga. in August of 2017, or, more accurately, the United States every day since November 8, 2016.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Time has been kind to Camelot, which is ironic, since complaints about its abuse of time (even devoted fans tend to find it overlong) have dogged the film since its release. No longer denounced for being out of step with the changing tastes of the '60s, Camelot now belongs to the forgiving rear-view gaze of Classic Hollywood. The up-and-coming stars in its cast are now revered film industry veterans. The traditional style of filmmaking employed, one lambasted for being creakily old-fashioned during the youthquake '60s, is now revered for its scope and grandeur...all devoid of CGI enhancement. And its melodic score now hearkens back to an era when a timeless traditionalism defined what we came to know as musical theater.

Yet, Camelot remains unique in that it is one of those films whose dividing line of opinion never seems to shift. I've never known of anyone who hated the film to ever come around to a more favorable opinion over time, similarly, those who started out loving it (as I do) can't be talked down from our cloud no matter what detractors say.

I can't speak for everyone, but I guess back when I was 11-years-old, maybe I just took it to heart when Arthur said at the end of the film, "What we did will be remembered."

|

| "Camelot" kicked off the 1967 holiday season when it premiered in San Francisco on Wednesday, November 1st, for a reserved seat, roadshow engagement (maximum ticket price $4) at the Coronet Theater |

King Arthur's Camelot took on the role of a Himalayan lamasery in the 1973 musical Lost Horizon

Camelot was revived on Broadway in 1980 with Richard Burton recreating his Tony Award-winning role as Arthur. When Burton succumbed to ill health in 1981, Hollywood's King Arthur—Richard Harris, then 51-years-old—stepped into the role. Harris would go on to purchase the rights to the stage production and toured with Camelot for six more years. This production, co-starring Meg Bussert as Guenevere and Richard Muenz as Lancelot, was broadcast on HBO in 1982 and is available on YouTube.

Richard Harris had quite the recording career, releasing several albums throughout the '60s and '70s. His biggest success came with 1968's Grammy-nominated album A Tramp Shining, which featured the #2 Billboard hit, the talk-sing version of MacArthur Park. I never owned that now-rare curio, but a particular favorite I never tire of listening to is Harris' guest stint as "The Doctor" (talk-singing his way through Go To The Mirror with Steve Winwood and Roger Daltrey) on the 1972 studio recording of Tommy, The Who's double-LP collaboration with the London Symphony Orchestra and a host of guest artists.

"Camelot" - 1967

Don't let it be forgot

That once there was a spot

For

one brief shining moment

That was known as Camelot.