“When she was good

she was very very good, but when she was bad she was better.”

In all matters practical, Harriet Craig is the perfect wife.

Beautiful and poised as a hostess, attentive and spuriously deferential to her adoring

husband Walter; Harriet runs their tastefully elegant upper middle-class home with

the efficiency and warmth of a science lab. In that curious definition of “housewife”

indigenous to the moneyed set, Harriet neither cooks nor cleans, raises no

children, and has no job. She merely spends every waking hour running roughshod

over the harried staff of housekeepers (servants, as she likes to call them),

even going so far as to engage Clare, her grateful, poor-relation cousin, as free

labor. All in the service of creating the perfectly clean, perfectly orderly,

perfectly loveless home. Trouble arises when Harriet, fearful that a job promotion for her

husband might loosen the short tether she has kept him on for the entirety of

their marriage, attempts to broaden the scope of her manipulation.

The possessive title of Craig’s Wife, which both the 1928 silent (now considered lost) and the 1936 Rosalind Russell film adaptations retained, hints not only at the original play’s dated mindset, but subtly of its narrative thrust. In both versions Harriet is obsessed with her image and social position and goes to extreme lengths to prevent her name (that of being Craig’s wife) from being involved in any scandal.

Updated for the '50s, Harriet Craig wisely jettisons a distracting murder/suicide subplot that figured significantly in Craig’s Wife and instead settles itself firmly in traditional Crawford territory: a domineering woman attempting to manipulate the lives of those around her. Though melodramatic in structure, this suburban domestic cautionary tale is directed with an appealingly light touch by Vincent Sherman (who also directed Crawford in The Damned Don’t Cry and Goodbye My Fancy), getting overall relaxed performances from the cast that contrast to good effect with Crawford’s appropriately starchy overemphasis.

And therein lies one of the essential guilty pleasures of Harriet Craig (and to the same degree, Crawford’s Queen Bee): it’s like watching Mommie Dearest with the genuine article. I like Crawford very much when she’s good, but she is untouchable playing bad. She is such a raving monster in Harriet Craig that the DVD would not be out of place in a store's horror movie section.

Copyright © Ken Anderson

If ever there was an actress about whom the above quote applies

(wholeheartedly and in all its transmutations) — it’s Joan Crawford: one of the

few actresses I find equally fascinating whether she’s delivering a good

performance or gnawing at the scenery. An actress capable of sometimes

astonishing emotional subtlety, what with the quicksilver flashes of tenderness or

wounded vulnerability those fabulously expressive eyes of hers could convey; she was equally enjoyable as an over-the-top, tough-as-nails,

slightly mannish, bitch-goddesses.

Harriet Craig, the

story of a woman who takes the role of housewife to its literal and tragic

extreme, is a film that had been on my “must see” list since the early '80s when

someone informed me that Crawford’s daughter Christina (she of the incendiary Mommie Dearest) recommended it along

with Queen Bee as the two films to see if you wanted to get a glimpse of what the real Joan Crawford was actually like. Already

acquainted with the extravagant camp of Queen Bee, I finally got to see Harriet

Craig back in 2007 when TCM hosted a Joan Crawford marathon.

The verdict? Well, as a representative page carved out of the

post-Mommie Dearest Joan Crawford

mythos, Harriet Craig doesn't disappoint. On the contrary. The film is full of so much melodrama and

overheated emotion that for long stretches of time it feels as if you’re

watching Joan Crawford as Faye Dunaway portraying Joan Crawford. Harriet

Craig (the third screen incarnation of George Kelly’s 1925 Pulitzer

Prize-winning play Craig’s Wife) is in

many ways the quintessential Joan Crawford vehicle. Drawing upon little more

than the same standard-issue icy imperiousness she brought to almost all of her

post-MGM roles (regrettably, she doesn't slap anyone here, but that’s about the

only thing missing from her usual arsenal), Joan Crawford and her grande dame of the screen image are so

perfectly suited to Harriet Craig, it feels as though the role had been written expressly for her.

|

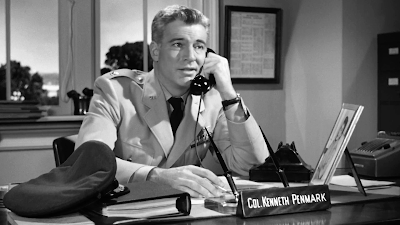

| Joan Crawford as Harriet Craig |

|

| Wendell Corey as Walter Craig |

|

| K.T. Stevens as Clare Raymond |

|

| Harriet Craig's cousin Clare, pretty much where Harriet likes to keep her at all times |

The possessive title of Craig’s Wife, which both the 1928 silent (now considered lost) and the 1936 Rosalind Russell film adaptations retained, hints not only at the original play’s dated mindset, but subtly of its narrative thrust. In both versions Harriet is obsessed with her image and social position and goes to extreme lengths to prevent her name (that of being Craig’s wife) from being involved in any scandal.

Much in the manner that the title of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler suggests the emotional

remove of its protagonist from her married identity of Hedda Tesman, the revamped

Harriet Craig is less about a woman’s

fear of losing her social status as it is about her full and complete fixation

on the marriage state as a means of obtaining emotional and financial security for herself. The husband is merely a means to an end.

|

| Craig's Law "Marriage is a practical matter. A man wants a wife and a home, a woman wants security." |

Updated for the '50s, Harriet Craig wisely jettisons a distracting murder/suicide subplot that figured significantly in Craig’s Wife and instead settles itself firmly in traditional Crawford territory: a domineering woman attempting to manipulate the lives of those around her. Though melodramatic in structure, this suburban domestic cautionary tale is directed with an appealingly light touch by Vincent Sherman (who also directed Crawford in The Damned Don’t Cry and Goodbye My Fancy), getting overall relaxed performances from the cast that contrast to good effect with Crawford’s appropriately starchy overemphasis.

|

| Mr. Craig, feeling amorous; Mrs.Craig, sizing up the matrimonial checks and balances |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT

THIS FILM

A common criticism leveled at the film adaptation of Mommie Dearest was that its screenplay

appeared to have been cobbled together from old Joan Crawford movies. Looking

at Harriet Craig it’s hard to argue

that point. The fictional Harriet Craig is every bit the neat-freak obsessive

that Crawford was made out to be in real life, complete with a poverty-motivated

backstory not dissimilar to Crawford’s own. So closely does Harriet Craig hew to our common perception

of Joan Crawford as an anal-compulsive nightmare, entire scenes of Harriet

going ballistic over some housekeeping transgression could be excised,

colorized, and inserted into Mommie Dearest with disconcerting ease.

And therein lies one of the essential guilty pleasures of Harriet Craig (and to the same degree, Crawford’s Queen Bee): it’s like watching Mommie Dearest with the genuine article. I like Crawford very much when she’s good, but she is untouchable playing bad. She is such a raving monster in Harriet Craig that the DVD would not be out of place in a store's horror movie section.

PERFORMANCES

The much-maligned Joan Crawford is one of my favorite

actresses. Even taking into account her mannered acting style and the severe,

exaggerated appearance she adopted as she matured, to me she remains the most

consistently interesting of the classic leading ladies of the silver screen.

Truth in fact, I think I like her to a great extent because of her stylistic excesses. It’s often said of Crawford that

she was more a movie star than an actress, but I’ve never found her to be any

more one-note than respected studio-system stars like Cary Grant, Katherine Hepburn

or Humphrey Bogart. I just think it’s a matter of taste. Personally, I never

had much of a stomach for

Cary Grant and find him to be one of the more arch and artificial stars (to

borrow a line from Singin’ in the Rain)

in the Hollywood firmament. Crawford, for all her studied emoting is a fascinating screen presence, and while only occasionally genuine, is always interesting.

Like most that have achieved and sustained movie star status,

Crawford’s screen persona and perceived private personality were so

intrinsically intertwined that, intentionally or not, her roles came to be imbued with a voyeuristically autobiographical essence. A phenomenon with Crawford’s

work that has oddly increased, not lessened, over the years. There’s no way to watch Harriet

Craig today without being continually hit in the face with the Crawford mystique.

When scenes are not suggesting some passage from the Mommie Dearest canon of obsessive perfectionist, they’re recalling the

haughty shrew characterization she fairly patented in the look-alike films that come under the heading “Joan Crawford vehicles.”

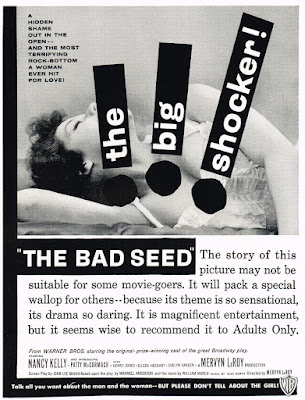

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Were I writing about Harriet

Craig back in the '60s or '70s, I would be declaring the film outdated and its

heroine hopelessly out of touch with the ways men and women interact. But here we

are in 2012 and Harriet Craig’s rather cold-blooded philosophies seem to be depressingly right in step with the times. In a comment to my previous post on The Bad Seed, a reader observed how the

confidence and sense of entitlement displayed by Patty McCormack’s Rhoda would likely make her a CEO in today’s world. Similarly, I think Harriet Craig’s

calculating pragmatism when it comes to love and marriage would today land her

a bestselling book deal and make her the darling of the misguided, post-feminist set drawn to reality-TV contests in which women strike bargains to be snapped up by so-called eligible bachelors, or read books that provide "rules" for getting a husband. Making the talk-show circuit, Harriet's 1920s philosophy would no-doubt be seen as "empowering."

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

In appraising Joan Crawford’s Harriet Craig side by side with Rosalind Russell’s Craig’s Wife, I’d say that Russell’s is unquestionably

the better performance (Russell’s performance actually gave me waterworks at

the end), but Harriet Craig is the

better film. The changes made to the original plot result in a tighter

narrative and clearer central focus: Harriet’s pledge to herself never to wind

up like her mother. What it loses is largely due to the lack of depth in either Crawford's performance or the screenplay. Crawford's Harriet is perhaps too steely to inspire much in the way of empathy.

Still in all, the film is a fascinating look at the somewhat superhuman

expectations placed upon women in the achievement of the suburban ideal (add a

couple of kids, a nicer disposition, and some genuine feeling for her husband,

and she’s basically the perfect wife), and in a way, shows what happened to the

role of the film noir femme fatale after the war—she became queen of the house.

|

| A House is Not a Home |

.jpg)