"I am so excited because I'm gonna go to the High School of Performing Arts! I mean, I was dying to be a serious actress. Anyway, it's the first day of acting class—and we're in the auditorium and the teacher, Mr. Karp... ."

A Chorus Line - James Kirkwood & Nicholas Dante

I read recently that the estate of choreographer/director Michael Bennett is planning a 2025 Broadway revival of A Chorus Line to commemorate its 50th Anniversary (feel old yet?). A Chorus Line opened on Broadway in July of 1975, and I still have vivid memories of seeing the touring company when it played San Francisco in 1976. A theatrical experience that, to this day, has never been surpassed.

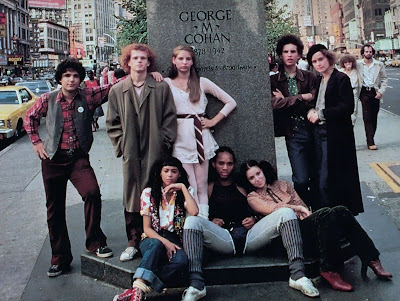

Fame's main characters represent a familiar cross-section of racial, cultural, and temperamental types, and as such, their experiences and relationships

tend to follow a fairly predictable arc. There’s driven Coco (triple threat

dancer/singer/actor); brash Leroy (dancer); shy Doris (actor/singer), troubled

Ralph (actor/stand-up comic); closeted Montgomery (actor/singer); solitary Bruno

(musician/composer), directionless Lisa (dancer or actor…whatever), and self-assured

Hilary (ballerina). These terse descriptions are in no way a diminution of the

characters or performances; merely an indicator of the built-in limitations of the

film’s multi-character structure.

In order to make room for songs and dance numbers while tackling everything from first love, illiteracy, teen pregnancy, drug abuse, and sexual exploitation; it’s necessary for Fame to resort to a bit of narrative shorthand. But the sublime triumph of the script and the film as a whole—which stands as a resounding testament to Parker and the film’s remarkably engaging cast—is that the abbreviated feeling of the various vignettes only leave you wanting more. No particular character or storyline overstays its welcome.

The end result, by virtue of the script's emotional vitality and the cinematic ingenuity of cinematographer Michael Seresin and longtime Alan Parker editor Gerry Hambling, is that the film achieves moments of real poignancy and passion.

Never less than an exhilarating, kinetic delight, Fame, instead of avoiding the “aspiring teens put on a show” tropes standardized by Judy Garland Mickey Rooney in those old MGM musicals, cozies up to them and updates these showbiz movie conventions in surprising ways. I found myself responding to clichés I thought I’d grown immune to ages ago.

If I have any criticisms at all, they’re of the subjective, nit-picking sort. For all the scenes that soar (the audition sequence is so good it could stand alone as a short film), there are head-scratchers like the recurring gag that asks us to share the ogling gaze of the adolescent boys peeking into the girls’ locker room. My problem isn’t so much with the fact that this sort of mainstreamed harassment has been normalized with “boys will be boys” rhetoric for too long; it’s that--given how Coco’s story plays out (a scene in which, once again, the director’s gaze renders us complicit in a woman’s sexual exploitation) it baffles me how a director can display so much sensitivity in some areas while revealing such a blind spot in others.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

As you can see from the photo above, Fame opened at Hollywood's Cinerama Dome on May 16th, 1980, which is the date I saw it and fell in love. Although I was a big fan of Alan Parker, the only names in the cast familiar to me were Barry Miller (who I thought was as terrific in Saturday Night Fever); Anne Meara (from the comedy duo [Jerry]Stiller & Meara); and most famously, Irene Cara. Fame is credited with launching Cara's career, but I remembered her from TV's The Electric Company and Roots, and on the big screen in Sparkle and Aaron Loves Angela.

Pre-release publicity was minimal, so I didn't know what to expect. Try to imagine, on that big Cinerama screen, what it was like to discover all these talented unknowns and hear for the first time those songs that are now almost too-familiar. A rousing, thrilling motion picture experience from start to finish. And I returned to see Fame many, many times over the summer. I was enthralled and surprisingly moved by it.

I was still attending film school at the time and working full-time at a bookstore, but within the short window of eight months, the releases of All That Jazz (December -1979), Fame (May -1980) and Xanadu (August-1980) became the dance film trifecta that inspired me to seek a career as a dancer.

The Roland Dupree Dance Academy on 3rd Street in LA is where I took my very first dance class (and eventually taught). Strange to think there was a time I didn't even know what legwarmers were and had to ask someone what a dance belt was (a thong/jock for male dancers); but it's here I studied ballet, tap, jazz, and modern. I wish I could remember when I took this photo, but I attended from 1980 to at least 1984.

As for Fame, one of the main reasons I always get teary-eyed during the film's finale is because in that spectacular display of goosebump-inducing talent (in which the "stars" they sing about are of the celestial and spiritual kind), the experience is like bearing witness to the dedication and hard work that goes into making an artist...into creating something beautiful. It has nothing to do with making someone famous.

A Chorus Line - James Kirkwood & Nicholas Dante

I read recently that the estate of choreographer/director Michael Bennett is planning a 2025 Broadway revival of A Chorus Line to commemorate its 50th Anniversary (feel old yet?). A Chorus Line opened on Broadway in July of 1975, and I still have vivid memories of seeing the touring company when it played San Francisco in 1976. A theatrical experience that, to this day, has never been surpassed.

I didn’t see the iconic musical’s most recent incarnation, the official 2006 Broadway revival, but I recall with equal vividness a conversation I had at the

time with a young dance student who’d just returned from seeing the NY

production, his first-ever encounter with A

Chorus Line. He raved about the dancing and thoroughly enjoyed the production,

but in the end was at a loss to understand the show’s reputation as a

groundbreaking classic: “I liked it…I just

don’t get what all the fuss was about!”

Said “fuss” being that

A Chorus Line won nine Tony Awards including Best Musical, the Pulitzer

Prize, ran for 15 years on Broadway, and was a seminal and influential pop culture phenomenon the world over.

While listening and resisting the impulse to explain the

significance of A Chorus Line by means of sign language (i.e., my hands around his throat), it became apparent to me that

this youngster’s reaction was perhaps born of his having grown up during the

Disneyfication years of Broadway. Raised in the post-The Lion King/Wicked

world of musical-theater-as-amusement-park-attraction, seeing a show consisting

of little more than a bare stage and a troupe of talented dancer/actor/singers

must have come as something of a shock.

Similarly, having been weaned on stunt-dance movies like Step Up #643 and dance competition TV shows like So You Think You Can Dance, it's also likely that this young man grew up with a perception of dance as athletic spectacle. I can't imagine Michael Bennett’s classic musical theater choreography looks very impressive when one has been conditioned to see dance performance in terms of Herculean feats of gymnastic strength, flexibility, and showboating "Look at me!" grandstanding of the sort antithetical to the “move as one” aesthetic of chorus work (“Don’t pop your head, Cassie!”).

Similarly, having been weaned on stunt-dance movies like Step Up #643 and dance competition TV shows like So You Think You Can Dance, it's also likely that this young man grew up with a perception of dance as athletic spectacle. I can't imagine Michael Bennett’s classic musical theater choreography looks very impressive when one has been conditioned to see dance performance in terms of Herculean feats of gymnastic strength, flexibility, and showboating "Look at me!" grandstanding of the sort antithetical to the “move as one” aesthetic of chorus work (“Don’t pop your head, Cassie!”).

However, there was one eye-opening takeaway from our conversation

which gave me a better grasp of why new generations might find themselves at a loss

to understand exactly what my generation found so powerful and innovative

about A Chorus

Line: personal self-disclosure as a metaphor for the significance of

the individual. A Chorus Line came

out smack in the middle of the "Me Generation," when the notion that the average person might have a story worth telling was still

something of a novelty.

In today’s climate of reality-TV, famous-at-any-price celebrity, and toxic social media oversharing; nothing dates A Chorus Line more than its cast of

dancers who shun having the spotlight shone on them. They recoil from being asked to talk

about themselves, don't like getting personal, and (horrors of horrors) resist being the center of attention. They'd prefer to communicate through dance, finding both dignity and self-respect by being allowed to do what they do for love. Even if it means being part of a corps of dancers; an anonymous, nameless, member of a chorus line.

As nakedly honest and heartachingly revelatory as those monologues seemed to me in 1976, I suspect that nothing disclosed by those characters would even warrant more than a handful of “likes” on Twitter today. This awareness of the degree to which the show business landscape has changed over the years became an ineradicable part of my revisiting one of my favorite musicals of the ‘80s: Alan Parker’s Fame.

As nakedly honest and heartachingly revelatory as those monologues seemed to me in 1976, I suspect that nothing disclosed by those characters would even warrant more than a handful of “likes” on Twitter today. This awareness of the degree to which the show business landscape has changed over the years became an ineradicable part of my revisiting one of my favorite musicals of the ‘80s: Alan Parker’s Fame.

|

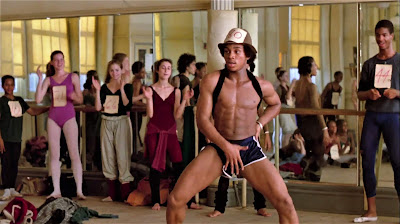

| Gene Anthony Ray as Leroy Johnson "I'm gonna be a good dancer. You will NOT keep me down!" |

|

| Maureen Teefy as Doris Finsecker "If I don't have a personality of my own, so what? I'm an actress. I can put on as many personalities as I want!" |

|

| Barry Miller as Ralph Garci (Raul Garcia) "That's the meanest high there is. It beats dope. It beats sex. I LOVE fucking acting!" |

|

| Paul McCrane as Montgomery McNeil "I mean, never being happy isn't the same as being unhappy." |

|

| Laura Dean as Lisa Monroe "I only ever wanted to be a dancer." |

|

| Lee Curreri as Bruno Martelli "You're not my age. Nobody's my age. Maybe I'm ahead of my time!" |

|

| Antonia Francheschi as Hilary van Doren "You see, I've always had this crazy dream of dancing all the classical roles before I'm 21." |

Fame, the American

feature film debut of British director Alan Parker (Bugsy Malone, Midnight

Express) was inspired—according to Parker, but denied by

producer David De Silva—by A

Chorus Line. Specifically, the dramatic potential suggested by the song “Nothing,”

which references a young dancer’s early experiences attending New York’s High

School of Performing Arts.

In a way, that makes Christopher Gore’s original screenplay for Fame something of a prequel to A Chorus Line; being that the film concerns itself with the formative experiences in the lives of eight young theater hopefuls at The High School of Performing Arts—from freshman auditions to senior graduation.

Taking the kids from roughly the ages of 14 to 18, the movie combines elements

of the coming-of-age film, the slice of life drama, and the backstage musical. Most

effectively (and entertainingly), Fame

also recalls and revitalizes those fondly-remembered high-school movies of my

youth: Up The Down Staircase, The Trouble With Angels, To Sir With Love, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. Blending elements of comedy and

drama, the four-year journey of the students of PA (High School of Performing

Arts) is, contrary to its title and the sanitized, rah-rah movies and TV shows

it inspired, a fairly dark, hard-shelled look at the blood, sweat, and tears

that go into pursuing a life in the arts. Ironically, the achievement of fame

doesn’t even factor into the fates of the characters.

|

| Ann Meara as Mrs. Sherwood |

|

| Jim Moody as acting teacher Mr. Farrell |

|

| Ilse Sass and Albert Hague as Mrs. Tossoff & Mr. Sharofsky |

|

| Debbie Allen and Joanna Merlin as honor student Lydia Grant and ballet instructor Miss Berg |

In order to make room for songs and dance numbers while tackling everything from first love, illiteracy, teen pregnancy, drug abuse, and sexual exploitation; it’s necessary for Fame to resort to a bit of narrative shorthand. But the sublime triumph of the script and the film as a whole—which stands as a resounding testament to Parker and the film’s remarkably engaging cast—is that the abbreviated feeling of the various vignettes only leave you wanting more. No particular character or storyline overstays its welcome.

The end result, by virtue of the script's emotional vitality and the cinematic ingenuity of cinematographer Michael Seresin and longtime Alan Parker editor Gerry Hambling, is that the film achieves moments of real poignancy and passion.

Never less than an exhilarating, kinetic delight, Fame, instead of avoiding the “aspiring teens put on a show” tropes standardized by Judy Garland Mickey Rooney in those old MGM musicals, cozies up to them and updates these showbiz movie conventions in surprising ways. I found myself responding to clichés I thought I’d grown immune to ages ago.

If I have any criticisms at all, they’re of the subjective, nit-picking sort. For all the scenes that soar (the audition sequence is so good it could stand alone as a short film), there are head-scratchers like the recurring gag that asks us to share the ogling gaze of the adolescent boys peeking into the girls’ locker room. My problem isn’t so much with the fact that this sort of mainstreamed harassment has been normalized with “boys will be boys” rhetoric for too long; it’s that--given how Coco’s story plays out (a scene in which, once again, the director’s gaze renders us complicit in a woman’s sexual exploitation) it baffles me how a director can display so much sensitivity in some areas while revealing such a blind spot in others.

Another of my gripes is the character of Montgomery. He simply

hasn’t aged very well. Putting aside his cringe-worthy monologue (“Gay used to

mean such a happy kind of word once.”), I give Fame credit for a positive portrayal of a gay character in a

mainstream film at a time when William Friedkin’s Cruising (1980) gave us yet another homicidal homosexual, and The Village People were

still tap dancing around their own queer identity (the deeply closeted Can’t Stop The Music was released just a

month later). But for me, Montgomery is a throwback to the days when movies thought

the best way to make a controversial character sympathetic was to render them as

a figure of pity.

As a teen grappling with his homosexuality, Montgomery feels isolated (in a Performing Arts School, yet!), but we in the audience can see he’s surrounded by all manner of gay kids. I don't expect anything as progressive as giving him a high-school sweetheart, but it would have been nice for his character to see that he wasn't the only one, and that "gay" could be happy. But, as written, Montgomery is content to stay on the sidelines, looking all alabaster and moony while playing Queer Eye for the Straight Guy & Gal to Doris and Ralph. At least he gets his own song (penned by McCrane).

As a teen grappling with his homosexuality, Montgomery feels isolated (in a Performing Arts School, yet!), but we in the audience can see he’s surrounded by all manner of gay kids. I don't expect anything as progressive as giving him a high-school sweetheart, but it would have been nice for his character to see that he wasn't the only one, and that "gay" could be happy. But, as written, Montgomery is content to stay on the sidelines, looking all alabaster and moony while playing Queer Eye for the Straight Guy & Gal to Doris and Ralph. At least he gets his own song (penned by McCrane).

Fame was released

three years before Star Search popularized

caterwauling as singing and made way for today’s barrage of I-deserve-fame-because-I-want-it,

celebrity-in-an-instant horse races like American

Idol, The Voice, and America’s Got Talent. Thus, one of the

things I find most gratifying about Fame is its realistic perspective and persistent

repudiation of the fame myths our culture keeps feeding young people.

I've always perceived A Chorus Line's glittering finale to be a much more heartbreaking and stark close to the show than its rousing melody would have us believe (after spending an entire evening getting to see these dancers as unique individuals, it is their fate to once again fade into chorus anonymity). Similarly, I've never felt Fame's exuberant theme song or its emphatic title to be really what the film is all about. The cocksure lyrics (in the context of the film, written by Coco, but actually written by Dean Pitchford to Michael Gore's music) may reflect Coco's determined quest for for fame and immortality, but the movie is more about the pain and sacrifices of chasing success. For me, the Oscar-winning song "Fame" is less a paean to the power of dreams than a pep-talk anthem to optimistic wishful thinking.WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

Fame is technically an '80s film, but its roots are clearly in the '70s. By this I mean it's a product of a '70s film sensibility. That decade-affixed mindset where creative choices were made appropriate to the material (swearing, nudity, drug use, sex) and not simply grinding out a feel-good musical to pander to the lucrative PG-rating demographic. I can't imagine a studio today releasing films like Fame or Saturday Night Fever with R-ratings. Some accounting actuary or focus-group survey would point out how much more money could be made from a PG release, and that would be the end of the very grittiness that gives these films their uniqueness.

I've always thought Fame was a very good movie, but in these post-High-School Musical years it has taken on the feel of a genuine classic. One look at the remake (a film I recommend you avoid at all costs) confirms that what Alan Parker and company have pulled off here is something very, very special. So good that even the watered-down TV show and fairly awful theatrical version couldn't defile it.

PERFORMANCES

An example of ensemble casting at its finest, I can't say there's a single performance in Fame I find any fault with. The veterans and novices deliver with equal assurance, a credit to Parker casting cannily close both to type and the relative demands of each role. To cite a particular favorite is less a comparative assessment of one player being "better" than another, so much as it's a recounting of my own emotional journey watching the film. Based on who I am and how I'm wired, some plot points and characters just spoke to me more persuasively than others.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

The music and dancing in Fame is glorious. I'm not exactly sure why, but it's one of the few '80s soundtracks that doesn't sound painfully dated. That's not to say the sound isn't very much locked into the time, for it is. But like the scores to many great musicals, it has a sound characteristic of the time and place depicted, it doesn't have that overly-trendy sound (like say Voyage of the Rock Aliens, or Earth Girls are Easy) that feels so corny and out of date it only has a distancing effect.

I've always thought Fame was a very good movie, but in these post-High-School Musical years it has taken on the feel of a genuine classic. One look at the remake (a film I recommend you avoid at all costs) confirms that what Alan Parker and company have pulled off here is something very, very special. So good that even the watered-down TV show and fairly awful theatrical version couldn't defile it.

PERFORMANCES

An example of ensemble casting at its finest, I can't say there's a single performance in Fame I find any fault with. The veterans and novices deliver with equal assurance, a credit to Parker casting cannily close both to type and the relative demands of each role. To cite a particular favorite is less a comparative assessment of one player being "better" than another, so much as it's a recounting of my own emotional journey watching the film. Based on who I am and how I'm wired, some plot points and characters just spoke to me more persuasively than others.

|

| The contentious relationship between English teacher Mrs. Sherwood and Leroy is very nicely played. Ann Meara really gives the inexperienced Ray a lot to work off of. He's at his best opposite her |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

The music and dancing in Fame is glorious. I'm not exactly sure why, but it's one of the few '80s soundtracks that doesn't sound painfully dated. That's not to say the sound isn't very much locked into the time, for it is. But like the scores to many great musicals, it has a sound characteristic of the time and place depicted, it doesn't have that overly-trendy sound (like say Voyage of the Rock Aliens, or Earth Girls are Easy) that feels so corny and out of date it only has a distancing effect.

|

| Hot Lunch Jam For sheer percussive energy, you can't beat this number. Cara's vocals slay |

|

| I Sing the Body Electric Each and every time I make a bet with myself that I'm not going to get waterworks from the graduation finale number. A bet I lose each and every time. |

|

| Fame choreographers Louis Falco (r.) & William Gornel |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

As you can see from the photo above, Fame opened at Hollywood's Cinerama Dome on May 16th, 1980, which is the date I saw it and fell in love. Although I was a big fan of Alan Parker, the only names in the cast familiar to me were Barry Miller (who I thought was as terrific in Saturday Night Fever); Anne Meara (from the comedy duo [Jerry]Stiller & Meara); and most famously, Irene Cara. Fame is credited with launching Cara's career, but I remembered her from TV's The Electric Company and Roots, and on the big screen in Sparkle and Aaron Loves Angela.

Pre-release publicity was minimal, so I didn't know what to expect. Try to imagine, on that big Cinerama screen, what it was like to discover all these talented unknowns and hear for the first time those songs that are now almost too-familiar. A rousing, thrilling motion picture experience from start to finish. And I returned to see Fame many, many times over the summer. I was enthralled and surprisingly moved by it.

I was still attending film school at the time and working full-time at a bookstore, but within the short window of eight months, the releases of All That Jazz (December -1979), Fame (May -1980) and Xanadu (August-1980) became the dance film trifecta that inspired me to seek a career as a dancer.

The Roland Dupree Dance Academy on 3rd Street in LA is where I took my very first dance class (and eventually taught). Strange to think there was a time I didn't even know what legwarmers were and had to ask someone what a dance belt was (a thong/jock for male dancers); but it's here I studied ballet, tap, jazz, and modern. I wish I could remember when I took this photo, but I attended from 1980 to at least 1984.

As for Fame, one of the main reasons I always get teary-eyed during the film's finale is because in that spectacular display of goosebump-inducing talent (in which the "stars" they sing about are of the celestial and spiritual kind), the experience is like bearing witness to the dedication and hard work that goes into making an artist...into creating something beautiful. It has nothing to do with making someone famous.

Scene from "Fame" 1980