"Doctor Spielvogel, this is my life, my only life,

and I'm living it in the middle of a Jewish joke!"

-Alexander Portnoy

The sexual revolution, at least as far as its depiction in motion pictures, caught American culture with its existential pants down. Nothing in our country’s repressed, Puritan past was designed to support the normalizing of human sexual desire, nor encourage its free expression as a thing of joy and beauty. Advancements in science may have given us “The Pill,” evolving social mores gave rise to Women’s Liberation, and the ‘60s Youth Movement challenged traditional codes of sexual conduct, but these progressive winds of change were no match for the profound, overarching influence of the moral dogma of organized religion.

The paradox of American culture has always been that while we are a peculiarly sex-obsessed nation, we nevertheless hold deeply-rooted, firmly-ingrained mindsets conjoining sex with sin, fun with shame, and feeling good with being bad. Currently, shamelessness is holding firm as America's defining social characteristic, but for the longest time, the country's most thriving industry and chief export has been guilt.

|

| Catholic Guilt: Fear that you're disappointing God Jewish Guilt: Fear that you're disappointing your mother |

When Hollywood jumped on the sexual revolution bandwagon, it did so with predictable results. It embraced the movement’s most marketable, superficial characteristics (nudity, profanity, sexual explicitness) while failing to adopt its corresponding philosophy of self-acceptance and self-love. Thus, in a surprisingly brief span of time, we were treated to a rash of hip, youth-oriented films cloaked in the timeliness of the “new permissiveness,” yet possessed of the age-old “no sex without guilt-induced moral compensation and/or punishment” mindset.

By way of example: during the early bloom of the sexual revolution, and later, during its waning days, two major movie studios released controversial, big-budget, high-profile films dealing with sexual liberation vis-à-vis the dilemma of religious guilt; the first (ostensibly) comedic, the second, tragic. In 1972, Warner Bros. released Portnoy’s Complaint, a curiously humorless comedy examining male compulsive sexuality through the prism of Jewish Guilt. In 1977, Paramount released Looking for Mr. Goodbar, an unrelentingly grim look at female compulsive sexuality through the prism of Catholic guilt.

Two films very different in tone, yet uniquely similar in reflecting our society’s insistence on using religion as a tool to punish ourselves for our natural, healthy interest in sex. A dilemma about which a Mr. Alexander Portnoy would like to lodge a complaint.

|

| Richard Benjamin as Alexander Portnoy |

|

| Karen Black as Mary Jane "The Monkey" Reid |

|

| Lee Grant as Sophie Portnoy |

|

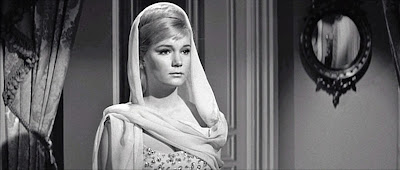

| Jill Clayburgh as Naomi |

|

| Jeannie Berlin as Rita "Bubbles" Girardi |

Alex Portnoy’s diagnosed complaint, briefly stated, is that at age 33, he finds it near-impossible to reconcile his intellect and strong social conscience (he’s a NYC lawyer who works to help the poor) with his compulsive preoccupation with sex…the more perverse, the better. Worse, it’s a libidinous obsession from which he derives virtually no pleasure due to overpowering feelings of guilt and the certainty that, in the end, he is bound to be punished for his impure thoughts and deeds. Faulting his early home environment as the source of his “What’s so bad about feeling good?” anxieties, adolescent Alex resorted to obsessive masturbation and erotic fantasy as a means of coping with his controlling, suffocating mother (who wanted him to be the Perfect Son), and his fault-finding, perpetually constipated dad (who wanted him to be the Perfect Jew).

“Doctor, do you understand what I was up against? My wang was all I really had to call my own!”

When Alex meets Mary Jane Reid, an equally oversexed fashion model who earned the nickname the Monkey after inventing a unique sexual position (the details of which we’re mercifully spared), he thinks he has at last found the shikse girl of his pornographic dreams. But alas, their relationship reaches an impasse upon the realization that, outside of the bedroom, it’s their spiritual fetishes that cause all the problems. Mary Jane nicknames Alexander "Breaky"...in reference to his being her breakthrough boyfriend. You see, Mary Jane, who suffers from low self-esteem, is looking for a man of intelligence and refinement to rescue and reshape her; in essence, treat her like an ongoing renovation project. Meanwhile, Portnoy is merely looking for a woman self-loathing enough to be his enthusiastic partner in self-degradation.

|

| Alex reacts to Mary Jane moving her lips as she reads |

On the printed page of Philip Roth’s controversial 1969 bestseller (written as a monologue relayed by Alexander to his analyst), Portnoy and his attendant complaint played like the impudent heterosexual answer to the homosexual audacity of Gore Vidal’s 1968 bestseller, Myra Breckinridge. Both novels used satire to assault late-60s sexual sensibilities, their sacred prose justifying their profane subject matter. On the screen, however, their respective film adaptations suffered considerably in translation. Chided for being made by directors apparently selected for their ability to completely misinterpret the original texts, both films were resounding bombs at the box office, but for polar-opposite reasons: the X-rated Myra Breckinridge was considered too vulgar; the R-rated Portnoy’s Complaint was criticized for not being vulgar enough.

While the whole “How did they ever make a movie of Lolita?” stuff surrounding Stanley Kubrick's 1962 film of Nabokov's novel was before my time (Oh, I was around, just too young to remember it); I fully recall the hubbub surrounding the unlikelihood that anyone could make a movie of Portnoy’s Complaint. When the film was released (perhaps a year too late in terms of public interest), fans of Roth’s novel, likely anticipating something combining the comic coarseness of Mel Brooks with the satirical wit of Woody Allen, were shocked to discover that one of the most talked-about books in American literature had been neutered and watered-down to such a degree that it resembled nothing more daring than a particularly smutty episode of Love, American Style. A coy, almost circumspect R-rated adaptation devoid of nudity, unless you count 33-year-old Richard Benjamin’s prominent man-boobs.

Critics lambasting the film found blame easy to affix, for acclaimed screenwriter Ernest Lehman (Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, North by Northwest, Hello Dolly!, The Sound of Music, Sabrina) pretty much did everything: he served as producer, writer, AND director (his debut/swansong).

The talented Jeannie Berlin somehow manages to escape her thankless bit role as Bubbles Girardi with her dignity intact. Berlin, who previously appeared in The Baby Maker, is the daughter of Elaine May, who for a time was up for the role of Sophie Portnoy.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

While my adolescent moviegoing memories are peppered with age-inappropriate films I was granted access to thanks to the lax enforcement of the motion picture code at my neighborhood theater, Portnoy's Complaint doesn't number among them.

I was able to get away with seeing X-rated 1969 releases like Midnight Cowboy and Last Summer largely due to my recently-divorced mom’s busy work schedule (she welcomed any opportunity to get my sisters and me out from underfoot), and my ability to convince her that not only was I mature beyond my years, but that these films were Oscar-caliber important works of cinema art. Alas, by 1972, my mom had remarried, so along with having another individual policing my comings and goings, I also had a mom who had more time to read.

Thus, as was the case with the equally-forbidden Myra Breckinridge, my mom having read Portnoy’s Complaint guaranteed that there was no way in hell she was going to allow me to see it. I was in no position to press the point, lest they catch on that for at least a year (I was 14 at the time) I’d been sneaking their hardback copy of Roth’s jaw-dropping book to the bathroom for “inspiration.”

|

| I don't know if it's a case of Richard Benjamin being far too old or Lee Grant being far too young, but this mother and son look more like husband and wife |

There aren’t many of Portnoy’s exploits I’d have the stomach to see rendered in widescreen color and enacted by Richard Benjamin, so the fact that Lehman resorts to so many modesty-concealing devices in a film almost entirely about sex may seem hypocritical, but it’s perfectly fine with me. What’s less easy to take is its depiction of women (seen from Portnoy’s gynophobic perspective, they’re either objects or grotesques), and its leaden humorlessness. Claims of anti-Semitism aside, the biggest crime committed against Roth’s novel is that Lehman, while maintaining much of the book's dialogue, somehow had the laughs surgically removed. Were not for Lee Grant’s amusing take on the Jewish mother stereotype, Portnoy’s Complaint would be an entirely laugh-free affair for me.

Portnoy’s Complaint is not perfect by a long shot, but the minute Karen Black appears (at the 38-minute point), it morphs, right in front of my eyes, into a movie worth watching. All at once, Portnoy’s Complaint stops feeling like a broadly-played TV sitcom thanks to Black's ability to find the humanity in a character written as the punchline to a Playboy magazine dirty joke. Suddenly, in exploring Alex’s relationship with Mary Jane, the film feels at last like it has something to say about the crippling effect of selfish love (the infantilizing Jewish mother) and the dehumanizing side of the sexual revolution (the empty pursuit of physical pleasure as a substitute for emotional intimacy). Lehman’s Portnoy’s Complaint is not Philip Roth’s (you can tell from the lush, jarringly incongruous Michel Legrand score), but it’s Lehman’s sincere attempt to tell an Inability To Love Story.

Unkind critics were quick to point out that after Goodbye, Columbus (1969), Richard Benjamin had made a career out of being a Philip Roth surrogate. Similarly, it was not lost on many that after garnering an Oscar nomination for Five Easy Pieces (1970), Karen Black never met a trollop role she didn't like.

PERFORMANCES

Not many people associated with the making of Portnoy’s Complaint look back on the film with fond memories. Ernest Lehman has said he was disappointed in the outcome, and Lee Grant in her memoir I Said Yes to Everything not only recalls the occasion of having to throw Lehman off his own set for acting like a tyrant (Grant, who became an award-winning director soon after, took over the directing chores of her hospital scene that day), but remembers how seeing the final result made her “...shrink back in horror. It was not a good reflection of Jewish Family Life.”

|

| The Portnoys Lee Grant and Jack Somack as Alex's overdramatizing parents. Grant was only 13 years older than Richard Benjamin |

Grant’s "I said yes to everything" philosophy—born of having spent 12 unemployed years on Hollywood’s McCarthy era blacklist—may account for her appearance in the film, but she really has nothing to be ashamed of. Scenes written as broad as a barn are salvaged by the anxious energy behind Grant’s delivery and timing. Her Sophie Portnoy may be a hysterical neurotic whose clinging over-concern emotionally scars her son for life, but she’s never a monster. Besides, her behavior, as we learned from the immortal words of Belle Rosen (The Poseidon Adventure), “Comes from caring.”

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

To read Portnoy’s Complaint is to realize the significant role imagination and ingenuity must have played for sexually curious adolescents raised before the days of Playboy, television, and mass-market porn. When I watch the film adaptation, I’m reminded of the degree to which sex and sexuality were the predominant cultural templates of adulthood when I was growing up. The ‘70s were so flooded with pop-culture references to the new sexuality that a defining trait of my adolescence was a race to grow up due to the nagging sense that I was missing out on something.

I read Portnoy’s Complaint (in installments, see above) at an age when I was far too young to know what it was really about. But Roth’s frank and explicit descriptions of adolescent sexual desire and self-experimentation were so true and on-point, it crossed gender, cultural, and sexuality lines. It was hard to read that book without feeling in some ways embarrassed—if not exposed—that ANYONE else entertained (let alone wrote down) obscene scenarios and vulgar imaginings of the sort I’d barely acknowledged to myself.

In re-reading the novel before writing this essay, what strikes me now, some 46 after my first encounter with Portnoy and his neurotic concerns, is that the single most shocking thing about Portnoy’s Complaint is not its language or the particulars of the activities described: it's the honesty. It’s Philip Roth speaking about the reality of life (his life, anyway) without concern for decency, religious propriety, respectability politics, or perpetuating the lie of pornography that airbrushes away the unpleasant details in order to sell us the consumer-ready result.

As someone raised Catholic, I relate to Portnoy’s struggles with his Jewish identity. I relate to the guilt, the issues of religious contradictions, the "good boy" syndrome, and the attempt to breach the dichotomy on matters relating to sex and sexuality. It’s also clearer to me now that there was a method to Roth’s madness. The much-discussed language and snickered-about “dirty stuff” weren’t for sensation; it was an assault on sexual hypocrisy. It’s what many people today fail to grasp about revolution and resistance: in order to overthrow a dominant social order, you need honest assault and confrontation. There’s no room for civility.

|

| "Why is every little thing I do for pleasure in this life immediately illicit - while the rest of the world rolls around laughing in the mud!" |

During the film's final act, when Alex has a reckoning with himself and is banished to a life of impotence by The Judge (Alex's conflicted conscience voiced by John Carradine. And for the record, the same fate meted out to Jack Nicholson's equally floundering sexual basket-case in Carnal Knowledge), I have to admit that Richard Benjamin is exceptionally good, as is the writing (mainly belonging to Roth). The very real confusion over how to navigate one's way through the influences and injuries of one's past, why it hurts so much to be human, the sad inevitability of having to look at yourself in order to change...it has the ring of impassioned truth and it succeeds in being a very moving moment in a film with very few traces of recognizable humanity beyond Karen Black's performance.

Before it morphed into the commodified alienation of the singles bar scene dramatized in Looking for Mr. Goodbar, the sexual revolution was (albeit briefly) a legitimate effort to wrest sex away from the chains of guilt and repression. A call to newfound spiritual and physical freedoms presented a challenge for us to be moral beings in a world of moral relativity.

Before it morphed into the commodified alienation of the singles bar scene dramatized in Looking for Mr. Goodbar, the sexual revolution was (albeit briefly) a legitimate effort to wrest sex away from the chains of guilt and repression. A call to newfound spiritual and physical freedoms presented a challenge for us to be moral beings in a world of moral relativity.

To live through the sexual revolution only to arrive at a time when the prepackaged, bullshit Disney-porn lie of something like E.L. James’ Fifty Shades of Grey passes for sexual liberation, is to understand that the true legacy of Philip Roth’s novel is its brazenly honest look at the human condition, not its profane reputation.

The movie...not so much.

BONUS MATERIAL

|

| WEB OF STORIES Click on the link to see Philip Roth speaking briefly about the films made from his novels |

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2018