“Back home down South, I could do no right.

When I moved out West, I could do no wrong.”

The quote is attributed to my late stepfather—a native Georgian who was light-skinned, green-eyed, and had a natural mane of wavy, reddish “Cab Calloway hair" that (according to him and which I don't doubt for a second) drove the ladies to distraction—on one of the rare occasions he spoke to me about the duality of his experience growing up bi-racial in the segregated Jim Crow America of the ‘40s and ‘50s.

It was typical of my stepdad, the quintessential “man of few words,” to capture the entire swath of his racial reality with such astute economy. When he was young, the inflexible Black-White binary of the segregated South disregarded his mixed ancestry. And though he self-identified as Black, how he presented didn’t fit the accepted (and arbitrary) stereotypical distinctions, so he was regarded with suspicion by Blacks and whites alike.

When he moved to the more integrated shores of California after the war, he discovered anew that how he self-identified was of little real consequence. Not with the ambiguity of his mixed-race appearance making him all things to all people. Integrationist whites, soothed by the familiarity of his European features, embraced him as the safe, “non-threatening” Black man. Among assimilationist Blacks, the toxic legacy of internalized colorism gave him his first taste of light-skin privilege as he was tagged socially as a matrimonial “catch” (“Imagine the beautiful, green-eyed, caramel-colored babies with ‘good’ hair we could have!”) while his white-adjacent appearance granted him unfettered access to professional and educational opportunities his dark-skinned colleagues were denied.

My stepfather's appearance and Scottish surname would have made it easy for him to pass, even if only on occasion of advantage, but he always claimed that to do so held no interest for him. Indeed, his rejection of his own white ancestry was so vehement (and never discussed) I always suspected it was linked to slavery and its heritage of rape.

The duality of experience born of the disparity between how one racially self-identifies and how one presents (and its emotional and psychological toll) is sensitively explored in Passing, the haunting debut feature film from director/screenwriter Rebecca Hall. Adapted from the 1929 book by Black female novelist Nella Larsen, Passing is a delicate, often heartbreakingly perceptive look at a very ugly American reality: the inherently corrosive nature of that illusory social construct we call race.

|

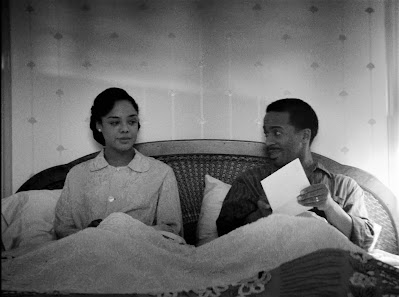

| Tessa Thompson as Irene Westover-Redfield |

|

| Andre Holland as Brian Redfield |

|

| Alexander Skarsgard as John Bellew |

Passing examines the complex dynamic that develops between two women, former childhood friends, who renew their association years after their adult lives have taken them on very different paths. The intimate interplay of contrast, curiosity, envy, and attraction that filters through their relationship also sets the stage for an insightful study of the many subtle, and not-so-subtle ways race, class, identity, sexuality, gender roles, and colorism intersect in a society that relies on labels and classification to decide who is and who is not allowed access to rights and freedom.

“Definitions belong to the definers, not the defined.” - Toni Morrison (Beloved 1987)

A member of the Black bourgeoisie and a model of racial uplift, Irene Redfield (Tessa Thompson) lives in the affluent Sugar Hill district of Harlem with her physician husband and two children. She spends her days in charity work (The Negro Welfare League), doting on her sons, and imperiously overseeing her had-it-up-to-here-with-your-snooty-attitude housekeeper Zulena. Irene’s sense of self is linked to her class, her fastidiously ordered life ("Ginger-ale and three drops of Scotch. Scotch first, then the ice, then the ginger ale"), and in having a keen awareness of the “rightness” of things.

But like the ceiling directly above her bed, there are cracks in the perfect façade. For one, her husband Brian (André Holland) longs to uproot the family to Brazil (whose absence of segregation fueled a prevailing Harlem Renaissance-era myth of it being a racial democracy). While Irene, who sleeps a lot and suffers from migraines, is given to saying things like “I have everything I’ve ever wanted” with the kind of unwavering certainly found only in the truly dissatisfied.

Irene’s sense of self is also linked to her identity as a Black woman...or more to the point, her identity as a middle-class Black woman. But, unlike her dark-skinned husband and children who have no choice but to confront the day-to-day racism she would prefer not to dwell upon, she can pass as white and does so on occasion, only temporarily, “for the convenience.” It’s on just such an occasion—with Irene occupying a whites-only space while “disguised as a white woman”—that Clare (Ruth Negga), childhood acquaintance and fearless (reckless?) force of nature, reenters Irene’s life.

So many years have passed that it takes Irene some time to even recognize Clare. But Clare (in a cinematic moment my mind instantly branded as iconic) sees Irene immediately and knows her. The unselfconscious directness of Clare's gaze reveals volumes about the kind of woman she is and why such indomitable assurance makes her both appealing and a little bit frightening. An effortless charmer and flirt, upon their meeting, Clare is all breezy self-possession to Irene's reticent geniality.

Although to be fair, Irene is the one who has the most to unpack in trying to process Clare's casual disclosure that for the past 12 years she has been living as a white woman. The former Clare Kendry of Harlem, daughter of a college-educated apartment house janitor, has cast aside her Black identity and reinvented herself as Clare Bellew of Chicago, wealthy wife and mother married to a successful (and staunchly racist) banker (Alexander Skarsgård).

"Fancy meeting you here. It's simply too lucky!"

What Clare calls lucky is running into “Rene” at a time in her life when the gains of passing (security and an avoidance of the marginalization and violence of racism) are beginning to feel unequal to the cost (literal and figurative self-erasure). Eager to reconnect with the community and racial identity she thought she’d be happier without, Clare aggressively pursues a relationship with the cautious Irene. Meanwhile, Irene, who feels attracted and repelled by Clare in equal, internally confounding measure, is concerned about Clare’s apparent indifference to the dangers of the course she’s embarking on.

And from this arises one of Passing’s central dramatic conflicts: The woman who has everything she ever wanted (and will do anything to maintain that stability) meets the woman who gets everything she ever went after (and will do anything to secure it for herself). The presumptive tease of the film's title suggests that the Black woman passing for white is the one living a lie. But the film reveals there are many ways to live one's life inauthentically.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

I’d neither heard of nor read Nella Larsen’s book Passing before seeing Rebecca Hall’s exceptional film (the most accomplished first screenwriting/directing effort I’ve seen since Kasi Lemmons’ Eve’s Bayou - 1997). I found the film to be absolutely riveting from start to finish, my emotional stake in the fates of the characters and outcome of the story fairly turning the film into a nail-biting thriller. The threat of violence is so entrenched in America's perpetuation of the racial hierarchy that a story touching on the topic of Black autonomy and self-governance feels (a term repeated often in the film) not safe.

From its dominant Black female perspective to its tackling of queer themes and racial ambiguity, Passing is unlike any other film I've ever seen. So floored by it all, my reaction to Passing was so effusively enthusiastic that my partner (in an effort to get me to stop talking about it, I suspect) surprised me with a copy of Larsen’s novella that following day. I raced through it and emerged with even greater respect for the miracle that Hall and her talented collaborators achieved in bringing it to the screen. I feel it's a motion picture and topic that couldn't have been made as effectively at any other time in history. How remarkable that a book written almost 100 years ago feels as though it was written yesterday. I’ve since seen Passing a total of four times and I still can’t stop thinking about it. And I’m not sure I want to.

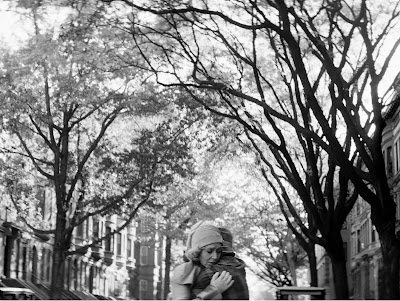

One obvious reason Passing keeps replaying itself over and over in my head is that it is such an extraordinarily beautiful film. The striking B&W cinematography by Eduard Grau (A Single Man – 2009) evocatively augments the film’s themes via images that poetically illuminate the many shades of gray that exist between the binary poles of black and white.

My fondness for films about women has been well-documented on these pages. Likewise, a sizable number of my most revered favorites have been movies exploring the dual nature of personality and the flexible margins of identity. Passing represents something of a jackpot on all fronts, not the least of its joys being that it’s that rarest of rarities, a movie about two Black women. Two Black women of intelligence, depth, and complexity whose actions propel the plot. Whose relationship exists independent of the male gaze and beyond a concern for the white gaze.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

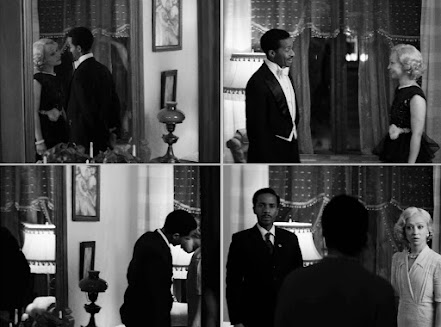

Passing's command of visual storytelling.

Passing is told from Irene's perspective. Whether it's the blurry fog we encounter when she's waking up from one of her many naps, or the admiring gaze cast Clare's way when she's not looking, the camera frequently provides insight into what Irene is feeling. The destabilizing effect Clare has on Irene is conveyed by showing events first as Irene sees them: the two images on the top and bottom left reflect Irene's internal certainty that her husband has succumbed to Clare's obvious charms. Then, as the events truly are: the top and bottom right images exhibit the spatial truth of the compressed mirror images that play tricks on Irene's eyes.

The Human Touch

(top l.) When Irene and Clare first meet in the tea room, Clare places her hand on Irene's only to have her withdraw from Clare's touch.

(top r.) Sometime later at a dance, Irene lets her defenses down enough to access her attraction to Clare, and reaches out and holds her hand.

(bottom l.) Much later in their association, Irene's suppressed feelings and overall discomfiture are funneled into an unfocused fear of a loss, manifesting in an uncontrollable trembling in that same right hand.

(bottom r.) Irene's right hand - "What happened next, Irene Redfield never afterwards allowed herself to remember. Never clearly."

"I only had to break it and I was free of it forever."

Potted Plant Teapot

|

| Unsafe Irene Breaks Things |

Passing's bleak suggestion that for some, absolute destruction is preferable to having to confront a painful and inconvenient truth finds its correlative in America's current socio-political climate where normalized fascism reveals a country's willingness to destroy democracy rather than confront illusion-shattering truths about its history.

PERFORMANCES

My earlier comparison of Passing to Eve's Bayou doesn't stop with their shared brilliance and rare look at a side and condition of Black life rarely depicted in films. They also have in common the dubious (and maddening) distinction of being critically well-regarded films totally ignored by the Academy Awards. But when it comes to films made by women and films about the Black experience, unless the woman is a domestic or slave and/or her life is characterized by the spectacle of suffering and trauma, awards never really seem to tell the whole story, do they?

Both lead actresses give nuanced and memorable performances in Passing. If I had my way Ruth Negga would WIN the Oscar for that tea room scene alone. She is phenomenal. She owns that scene in a way that's almost criminal. She's that good. She imbues Clare with a catlike canniness that is a touching balance of steely self-possession and vulnerability. A clearly fun gal to hang out with, Clare is like a Black Southern Belle, all extravagant gestures and florid expressions, capturing every eye effortlessly.

The radiant Tessa Thompson gives what I think is her best performance to date in an increasingly impressive career. She does so much with her eyes! It's a marvel to me how she does it, but she makes clear Irene's most subtle feelings and thoughts, taking us in and helping us to understand a character who doesn't fully understand herself.

In interviews, Passing director Rebecca Hall often stated that one of the questions she wanted to explore through her film is: What is the emotional legacy and psychological toll of a life lived in hiding? I think the arresting and challenging Passing offers many very compelling answers. Better still, it inspires a great many more questions.

BONUS MATERIAL

|

| Dona Drake (1914 - 1989) |

A fascinating tale of real-life “passing” can be found in the life story of one of my favorite screen supporting personalities. Dona Drake (nee Eunice Westmoreland), a Black, Florida-born actress, singer, dancer, and bandleader who passed for the entirety of her career. Though both parents were of Black ancestry, studio publicity declared Drake (who went by the names Una Villon, Rita Novella, Rita Shaw, and Rita Rio at various stages of her career) hailed from Mexico and was of French/Irish extraction. The beautiful and vivacious performer went on to be cast as "exotics" in a number of films throughout the '40s and '50s, principally as a musical-comedy performer, but occasionally given a dramatic role (she played Bette Davis’ Indigenous housekeeper in 1949s Beyond the Forest).

Another level of "passing" was added to Don Drake’s already fabricated biography when in 1940 she wed gay costume designer William Travilla (Oscar and Emmy-winning designer of Valley of the Dolls and Marilyn Monroe fame) in what is believed to have been a mutually-beneficial, studio-arranged marriage. You can read more about Dona Drake’s life and career HERE.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2022