|

| "If the monkey hadn't died, the show [movie] would be over." Sign backstage during the L.A. run of the musical version of Sunset Blvd. from the book "Close-Up on Sunset Boulevard," Sam Staggs 2002 |

Sunset Boulevard had its broadcast television premiere October 2, 1965, at 9 pm on NBC’s Saturday Night at the Movies. Being just seven years old at the time, this event came and went without incident or notice by me. When I did get around to seeing Sunset Boulevard, it was in the early '70s, when I was about 14 years old and a budding film buff in the first flush of a newfound infatuation with old movies.

My movie preferences at this age leaned toward age-inappropriate modern films oozing with New Hollywood permissiveness. But in 1971 Ken Russell’s The Boy Friend was released, and that film---a visually stunning, spoofish tribute to the musicals of the '20 and '30s that took my breath away--single-handedly inspired me to seek out and discover old movies.

A personal journey that happened to coincide with the then-peaking nostalgia craze.

Ignited by the popularity and influence of Bonnie and Clyde in the late '60s, America grew increasingly enamored of its recent past. A rose-colored love affair of exploration and escapism (the '70s were no picnic) that found expression in every corner of pop culture, from fashion to music. Classic films and their stars were especially popular with the younger generation, who responded enthusiastically to them for both their artistry and their camp appeal.

|

| 1971 - Everything Old Was New Again |

My own particular interest in nostalgia manifested itself in a fascination with movies headlined by former leading ladies of yesteryear. The more melodramatic, the better. I was especially taken with Grande Dame Guignol, which, if you're not familiar, are essentially monster movies for gay teens.

Grande Dame Guignol (or hagsploitation) are sensationalistic melodramas and horror thrillers centered around older actresses in roles that exploit or exaggeratedly play off the star's declined status and advanced age (by Hollywood standards, mind you, which is simply over 30) contrasted with their often over-the-top, prima donna behavior. Recognizable by their formula mix of deglamorization + histrionics + gerontophobia with a dash of kitsch and camp thrown in, their plots tended to be baroque variations on familiar monster movie tropes. Only the "monster" in this instance is usually a middle-aged woman who behaves violently or becomes unhinged after suffering some kind of emotional breakdown or traumatizing social outcast rebuff (imagine Stephen King's Carrie for the AARP set).

Empathy always drew me to the "villains" in these films: these larger-than-life women who suffered or were driven mad by their unwillingness or inability to surrender their outré, outsized fabulousness to the conformist dictates of age, gender, marital status, childlessness, standards of beauty...or sanity.

Even when they resorted to murder (which they always did), it was still kind of tough not to feel bad for them since their crimes were almost always pitiable acts of desperation and madness. Besides, from the film's point of view, the real crime these women were guilty of was growing old and ceasing to occupy their "natural" roles as either mother or wife, or desirable to the male gaze.

Queer Identification in Sunset Boulevard - Approximating the Female Gaze

As written, the character of Norma Desmond is a direct assault on postwar cinema's reassertion of rigid gender roles. Her dominance, sexual agency, and solitary independence are presented as an appropriation of masculine power; ergo, she's a monster. Joe Gillis's dependent status and physical objectification render him "the male feminized," which, in the eyes of the film, is an irredeemable sin.

Grand Dame Guignol movies were largely viewed as a comedown for the stars involved, but I credit them with introducing me to: Bette Davis (Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte), Joan Crawford (What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?), Tallulah Bankhead (Die! Die! My Darling!), Olivia de Havilland (Lady in a Cage), Barbara Stanwyck (The Night Walker), and Eleanor Parker (Eye of the Cat).

I’d never even heard of Gloria Swanson at the time, but when my older sister circled the plot synopsis of Sunset Boulevard in that week’s TV Guide, it sounded exactly like a horror movie to me, so I was looking forward to seeing it. (A weekly ritual my sisters and I shared in rotation was to go through the entire TV Guide when it arrived and circle every “must-see” movie and special scheduled.)

Of course, the noirish Sunset Boulevard – a grim melodrama that has a struggling screenwriter meet a bad end after hoping to take advantage of the comeback delusions of a fading silent screen star – is neither a horror movie nor an example of Grand Dame Guignol (at least not, to quote Norma, not “in the usual sense of the word”). But it shares enough similarities with those genres for me to have actually mistaken Sunset Boulevard for a hagsploitation horror movie the first time I saw it.

.

|

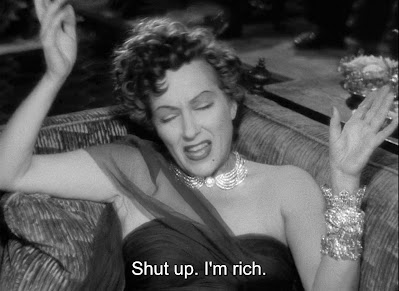

| Gloria Swanson as Norma Desmond |

|

| William Holden as Joe Gillis |

|

| Nancy Olson as Betty Schaefer |

|

| Erich von Stroheim as Max Von Mayerling |

Everything about Sunset Boulevard's set-up (from a screenplay by Wilder, Charles Brackett, and D.M. Marshman) is strictly Gothic Horror 101. The stranger-in-distress who happens upon a crumbling castle occupied by a mad scientist and henchman is a horror movie trope so timeworn it's parodied in The Rocky Horror Picture Show and countless Warner Bros. cartoons. Only in this instance, down-on-his-luck screenwriter Joe Gillis is the stranger in need, a decaying Beverly Hills mansion plays stand-in for the castle, and of course, it doesn’t take much imagination to picture fading silent screen star Norma Desmond as Frank N. Furter and Max as Riff Raff.

Gothic tradition gives us a mad scientist obsessed with regenerating dead human tissue; Sunset Boulevard has a mad actress obsessed with regenerating a dead career.

The horror indicators keep piling up in Sunset Boulevard as the Old Dark House trope morphs into the Villainous Crush device that always leads to the Domestic Incarceration machination from which our hero (antihero in this case) must escape. To my adolescent sensibilities, Sunset Boulevard was every bit as chilling as any horror movie I’d yet seen. More so, in fact. Well into Sunset Boulevard’s 110-minute running time…what with Franz Waxman’s ominous (Oscar-winning) score; John F. Seitz’s stark and shadowy Black-and-White cinematography; and the utterly unique strangeness of Swanson’s raptorial Norma Desmond…I was certain I was watching Creature Features: The Hollywood Edition.

So well had an atmosphere of "anything's possible" bizarreness been established that I was convinced there was going to be some kind of 11th-hour “big reveal” moment…something like Joe discovering that the only room in the house with a lock on it contained the mummified remains of Norma’s ex-husbands. Or that the film’s climax would involve an ax-wielding Norma stalking Joe and Betty through the halls of her Addams Family-chic gothic mansion.

Despite thwarting my cliché-fed, B-movie horror expectations at every turn, Sunset Boulevard nevertheless proved sufficiently dark of theme and weird of story to give me a good case of the willies that evening and a sleep full of nightmares (Norma’s advance to the camera at the end really freaked me out).

But numerous viewings over the years haven't truly altered my initial impression of Sunset Boulevard as a horror movie, only the syntax: I no longer see it as a horror movie, but it’s most definitely a horrific movie. A nightmare vision of Hollywood that qualifies as a grim antecedent to The Day of the Locust and They Shoot Horses, Don't They?

|

| Time Passages - Holden in 1950 and 1978 Twenty-eight years later and Joe is still hustling to make a buck in Hollywood. Billy Wilder (then 74) and William Holden (59) had their 4th screen collaboration in 1978's Fedora. A movie that, though unrelated to Sunset Boulevard, feebly sought to evoke memories of that superior film with its plot involving a down-on-his-luck movie producer (Holden) and a reclusive screen star (Marthe Keller). Critics felt Wilder would have been better off shooting Norma's Salome script. |

"There's nothing tragic about being fifty -- not unless you try to be twenty-five."

In life, aging and the passing of time are so subtle they're almost imperceptible. When you’re young, they’re measured in things acquired: experience, independence, wisdom; as you get older, they’re measured in things lost: hair, agility, time. And matters aren’t helped any by the fact that one’s chronological age (how old one is) and biological age (how old one feels) are rarely--if ever--in sync.

In Hollywood, where time is the enemy and aging is regarded as a bad career move, Sunset Boulevard sees the ironic tragedy in the story of a woman for whom time has stood still being overlooked by an industry that’s literally in the business of stopping time. The Dream Factory paradox is that Hollywood is only able to peddle the fantasy of eternal youth and beauty by callously discarding its manufactured idols the moment their images are tarnished by reality (i.e., age).

That’s where the horrific part of the Hollywood nightmare comes in. Are the stars who mutilate and starve themselves in an effort to hold onto youth considered "sane" because doing so keeps them in the game, and they understand that's how the game is played? Certainly, the public seems to think so.

In 2015, social media drew the ire of the late Carrie Fisher when Star Wars fans deemed the then-59-year-old actor to have "aged badly" since her Princess Leia in a metal bikini days.

Her response: "Youth and beauty are not accomplishments. They are the temporary happy by-products of time and/or DNA. Don't hold your breath for either."

|

| Is Norma's insanity that she can't distinguish fantasy from reality, or simply that she learned Hollywood's lessons all too well? |

"All cardboard, all hollow, all phony, all done with mirrors."

Sunset Boulevard’s allegorical use of Hollywood’s artificiality serves to underscore its themes related to our susceptibility to fantasy, the importance of maintaining one's authenticity, the easy corruptibility of our values, and the price of losing touch with reality.

And indeed, between the film’s use of genuine, Hollywood locations (Schwab's Pharmacy), real movie industry personalities appearing as themselves (Cecil B DeMille, Hedda Hopper), and silent-era star Gloria Swanson and silent-era director Erich von Stroheim playing characters that are NOT themselves, but kinda are… Sunset Boulevard blurs the line between fantasy and reality as freely as Norma herself.

In the 70-plus years since Sunset Boulevard’s release, Hollywood really hasn’t changed all that much. But the world HAS become a bit more like Norma.

Norma's cocooned narcissism finds its contemporary corollary in the normalized self-absorption of social media selfie culture, where delusions are allowed to run rampant in Instagram and TikTok accounts devoted exclusively to self-enchanted images of oneself. Norma would love it. The torturous regimen Norma undergoes in the name of self-rejuvenation, once the somewhat loony but practical province of those whose livelihoods are predicated on their appearance, is child's play compared to what the average person today is willing to subject themselves to under the marketing-friendly brand of "self-esteem."

Perhaps most remarkable of all, fame-culture and its attendant wealth-worship have turned America's working poor into the frontline defenders and protectors of the rich. The quickest way to pick a fight on social media these days is to criticize ostentatiously wealthy celebrities or question whether obscenely rich wealth-hoarders should perhaps pay proportionately as much in taxes as disabled veterans living on Social Security.

I've been told that when I go off on one of my windy jeremiads about what I deem to be the superiority of '70s films over the movies made today, my arguments can take on a tone not dissimilar to Norma Desmond lamenting post-silent-era cinema's lack of "faces" and bemoaning the smallness of "the pict-chas."

A Most Unusual Picture! - Movie poster tagline for Sunset Boulevard

The quotation that headed this essay - "If the monkey hadn't died, the show would be over" - only partially relates to the narrative logic suggesting that had Norma not been anticipating the arrival of an animal mortician, Joe Gillis would have never made it past Max at the front door.

I think the quote also speaks to the loneliness of Norma's life. Whether she considered the chimp to be a pet, a companion, or a child surrogate, it's easy to conjecture that if the monkey hadn't died, perhaps Norma wouldn't have been so desperately lonely. Arguably, Norma's loneliness is the source of much of her pain and madness. Certainly, loneliness and desperation are what prompt her to go full Grand Dame Guignol and all but kidnap and hold hostage a complete stranger.

Although, when speaking of a complete stranger who looks like William Holden...

BONUS MATERIAL

Clip from "Sunset Boulevard" 1950

This fuzzy screencap looks a bit like Dame Edna Everage is having a go at Norma Desmond (which sounds pretty fab, now that I think of it), but it's actually Mary Astor with Darren McGavin in a one-hour television adaptation of Sunset Boulevard. Broadcast in color on NBC December 3, 1956 as part of the anthology program "Robert Montgomery Presents," it was 2nd made-for-television version of the Paramount film. Available for viewing HERE.

Although Gloria Swanson herself had unsuccessfully tried to turn Sunset Boulevard into a musical for years, in 1993 Andrew Lloyd Webber, Don Black, and Christopher Hampton premiered their theatrical musical version of Sunset Boulevard in London's West End with Patti LuPone starring as Norma Desmond. The show had its pre-Broadway US opening December 1993 in Los Angeles at the now-defunct Shubert Theater in Century City with Oscar-nominated actress Glenn Close in the lead. I saw the production in January of 1994 and truly loved it. Especially the breathtakingly elaborate production and set design.

As magnificent as Glenn Close was, I was in near hysterics when it was announced on June 15, 1994 that Oscar-winner and personal fave Faye Dunaway was set to don Norma Desmond's turban when Glenn Close took Sunset Blvd. to Broadway (with lots of attendant ugliness involving Webber giving the shiv to role-originator LuPone). It mattered not a whit to me that Dunaway had heretofore never evinced even a glimpse of singing ability. We fans of camp knew exactly what her casting in the role augured: "Mommie Dearest, Live!"Alas, it wasn't to be.

In an 11th-hour twist worthy of Sunset Boulevard itself (screen star rejected!) on June 24th, word came out that Dunaway's services were no longer required and that Sunset Blvd. was to close. Cue the press circus reporting on the conflicting and litigious reasons for the decision. The trouble-plagued production moved on to Broadway, where it was a great success, winning several Tony Awards, among them Best Musical and Best Actress.