Spoiler Alert. This is a critical essay, not a review, so plot points will be revealed for discussion purposes.

Have you ever come across one of those hysterical clickbait links with a headline screaming, “You’ll be shocked to see what (insert any celebrity ...99% of the time, a woman) looks like today!” only to discover that the person has simply aged naturally?

Or maybe you've noticed that—while the posting of heavily filtered, augmented, and body-tuned selfies is nothing new—they all now seem to be aiming for the same standardized mannequin aesthetic.

ALL ABOUT EVE (1950)

Or you may have seen the male fitness influencer (who stays mum about his secret cycle of HGH injections) who cloaks run-of-the-mill narcissism in the aspirational rhetoric of discipline and self-mastery. Employing aggressive Alpha language (fight, power, winning, conquer pain), it all feels like obvious compensation for an underlying unease with what might be perceived as a “socially feminine” preoccupation with one's looks.

And then, perhaps you’ve had the misfortune of encountering the AI artwork of a “creator” who wants to share with you his/her depiction of the ideal in female beauty: Which somehow ALWAYS means a vacantly staring white woman with the exaggerated eyes and lips of a Bratz doll and a body of Jessica Rabbit cartoon proportions.

VEEP- 2019

Even my citing these examples reflects the hegemony of body politics that we all perpetuate, participate in, and endure. Underscoring how, as a society, we continue to intrude upon the personal, private domain of others (our bodies are our own and no one else’s business) by asserting that we all, collectively, have some kind of say in the matter. Consequently, our bodies and physical appearance come to significantly influence our experience of the world, our self-esteem, and in far too many cases, our mental health.

Where once fashion magazines and advertising were the primary suppliers of unrealistic beauty norms, now, selfie-culture (with its "take 500 photos to get the ideal one to post" standards of phone-filter perfection) makes sure that every moment of every day, we're bombarded with images of how we think we're supposed to look.

SWEET BIRD OF YOUTH (1963)

In The Substance, French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat takes a laceratingly frank look at bodies- our own and the bodies of others- and our relationship with them. Using vivid imagery and startling symbolism, Fargeat confronts the attitudes, conflicts, phobias, and fetishes we attach to our all-too-weak flesh with a take-no-prisoners bravado. Forcing us to examine how our reckless pursuit of beauty standards has blurred the jagged line between self-care and self-mutilation. And Fargeat does so without offering solutions, reassurance, or much concern for our comfort zones.

THE MIRROR CRACK'D (1980)

Only the second feature film from the gifted director/writer/editor, The Substance is a darkly surreal fairy tale exploring body image, beauty standards, aging, self-loathing, misogyny, disposable people culture, patriarchy, psychological violence, and two of my all-time favorite themes: dualism and the human desire to connect and be loved.

Though in so many ways unlike anything I’ve ever seen before, The Substance possesses a visual richness that pays homage to classic cinema while blazing an audaciously unique path all its own. Psychological, cultural, and emotional truths merge with a barely-linked-to-reality narrative that evokes a monstro-mutation of the cinema of our past: All About Eve, Showgirls, Death Becomes Her, The Portrait of Dorian Gray, Perfect, Black Swan, Carrie, and of course--

Sunset Boulevard (1950)

|

| This movie is 75 years old. A society really must have a serious talk with itself to explain how a woman losing her mind because she's turning 50 is still a thing |

Embodying the tagline of 1974’s The Day of the Locust: “It Happened in Hollywood, But It Could Have Happened in Hell,” The Substance is set in a present-day Hollywood of the mind—a Hollywood where it sometimes snows, people still read newspapers to find jobs, nighttime talk show hosts are Black, exercise TV programs are ratings blockbusters, and ‘80s/‘90s aesthetics...like legwarmers...have never really left.

The film's anti-heroine is once-popular, Oscar-winning actress Elisabeth Sparkle (it’s her real name; for we learn in school she was called Lizzie Sparkle, “the most beautiful girl in the world”…at least according to Fred in 10th-grade homeroom). Elisabeth is on the verge of an existential crisis.

|

| Demi Moore as Elisabeth Sparkle |

|

| Margaret Qualley as Sue |

The (de)evolution of Elisabeth’s career suggests perhaps ageism played a role in her no longer acting in movies (roles for women over 40 make up only 5% of available female film roles), leading her down the B-List showbiz path of TV aerobics guru -"Sparkle Your Life with Elisabeth" - and advertising spokesperson exploiting her catchphrase "You Got It!" A career in which her success and fame are entirely linked to her physical appearance and age-defying physicality.

Alas, age-defying doesn't mean age-less. On her 50th birthday, Elisabeth receives (in the harshest way imaginable) the world-shattering news that she and her long-running TV show are to be put out to pasture to make room for a tighter, firmer, younger version of both.

|

| Dennis Quaid as Network Executive (wouldn't you know it) Harvey |

As emphasized by the film’s Kubrick-esque camera angles and macro closeups, The Substance is partially an allegory about distorted perceptions. TV executive Harvey's lack of self-perception makes him think he's a charming winner instead of a bullying sociopath whose inner sense of inadequacy manifests in external outbursts of psychological violence. Always targeting women.

On the distaff side, Elisabeth's lack of self-perception is a kind of mind blindness. She has an inability to latch onto any yardstick of self-evaluation not linked to impossible aesthetic norms and the validation of the male gaze. Her lack of self-esteem manifesting in escalating internal (and later, VERY external) outbursts of self-directed violence...psychological, emotional, and physical. In fact, she hates herself.

.png) |

| The fact that an entire wall of Elisabeth's Barbarella spaceship-style penthouse is dominated by a floor-to-ceiling portrait of herself tells us everything we need to know about her priorities |

It can be said that Elisabeth's lack of inner substance—exemplified in her complete embrace of superficial beauty ideals that undermine her worth as a human—is the fatal character flaw that sets the conflict of The Substance in motion. Instead of directing her anger at a social construct that diminishes her in every way, she directs her anger at herself for failing to live up to these ridiculous standards. Still, it's impossible not to feel empathy.

One can always detect discernable traces of self-loathing behind the physical perfection-seekers of our culture, but since we're a society that values overachievement no matter how hollow the reward -as in celebrating "good" plastic surgery or the "quickest" fad diet- we reinforce the notion that "looking" like we're okay on the outside is more important than actually "being" okay inside.

That's one of the reasons why I think fame and celebrity are so sought-after by those plagued by self-disgust; though meaningless in the larger scheme of things, the external validation of strangers can work like lead to the kryptonite of introspection.

Letting others define you and tell you exactly what you need to be, do, and look like to make yourself worthy of love is a doctrine that clearly works for a great many people. Religions have been doing it for centuries, and they swear by it (literally).

Of course, the implicit caveat behind the conditional love and transitory admiration offered by celebrity and fame is the understanding that said "stars" must never change or age.

"Youth and beauty are not accomplishments. They're the temporary happy by-products

of time and/or DNA. Don't hold your breath for either." Carrie Fisher -2015

For someone like Elisabeth, being told that she's at the end of her career is like telling her she's at the end of her life. The Substance—an underground youth elixir that promises a younger, more beautiful, and more perfect version of oneself—enters Elisabeth’s life at the exact moment she starts to feel its impending erasure. How convenient.And while the promise of that little Day-Glo vial is irresistible and appears to be the solution to all of Elisabeth's problems, anyone who's read a Stephen King novel, watched an Amicus anthology horror film, or seen an episode of The Twilight Zone knows-

...there's always a catch.

|

| Whoopi Goldberg - Ghost (1990) |

That image above of the injected and divided egg yolk will have to serve as summary of how the drug known as The Substance works. Fargeat is far too compelling a visual storyteller (and it's all too far-out and surreal) for anything I write to do it justice.

I will say that The Substance does indeed create a new, fully formed, independent person from Elisabeth’s DNA (picture Botticelli’s "The Birth of Venus" reimagined by David Cronenberg); however, Sue, as she names herself, is more a “side” of Elisabeth than a new “version.”

The ultimate Odd Couple, Elisabeth and Sue, share an apartment and an irksomely inconsistent consciousness while living an alternating existence of one week on, one week off.

It’s a bit like if the adult, self-possessed part of me and the side that still compulsively bites my fingernails existed as two separate people. It’s definitely ME biting my nails; however, in most cases, it’s something I do without conscious awareness. I often “catch” myself biting my nails, which sounds absurd since it’s ME, yet that’s how it works. You’re one, yet it’s still possible to act as though you are disconnected from yourself.

Sweet Sue

|

| No one else, it seems, ever shared my dreams. And without you, dear, I don't know what I'd do. |

In Robert Altman's 3 Women (1977), Sissy Spacek plays a character named Pinky Rose (!) who cultivates a hyperfeminine personality that comes to dominate and drain the life force of her roommate Millie (Shelley Duvall). A similar dynamic develops between Elisabeth and Sue in The Substance, turning this already ingeniously assaultive allegory into an absolutely demented roar of anger confronting the horrific violence we’re willing to inflict upon ourselves (body and psyche) in the pursuit of unattainable perfection.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

I don't often write about contemporary films, but when I do, I've noticed that most of them tend to be of a "sort": Hereditary (2018), Black Swan (2010), Midsommar (2019), Maps to the Stars (2014), Nocturnal Animals (2016). This sort being movies that convey a sense of auteurist vision, independent daring, and a kind of artistic audacity that reminds me of that unpredictable, "Only in the '70s," off-the-wall quality that made so many films from that era so great. And so insane!

I love everything about The Substance: its immersive use of sound (incredible!), color, camera angles, editing, and locations. All is in service of the film's meticulously-crafted worldview. A worldview wherein absolutely everything feels excessive, yet nothing feels wasteful.

Best of all, I think it's a very smart movie. It knows what it wants to say and, by refusing to spell everything out, doesn't mind if what's being expressed is misunderstood. Indeed, in some ways, it could be said that The Substance dares you to like it.

A valid argument could be made that the film's points are made with a sledgehammer, but to that, I'd say, if in the year 2025 we're still having men legislate women's bodies, then perhaps a sledgehammer is necessary to get these (to me) obvious points across.

|

| These guys don't think you're hot enough. Daniel Knight and Jonathan Carley as Casting Directors |

I found The Substance to be compelling, grotesque, ingenious, and as sharp as a razor. It moved me and grossed me out, and the ending, in particular, is so poignant (major waterworks) that it’s a shame the scene itself is so difficult to watch. Speaking of which, I've seen The Substance four times—well, make that three; the first time shouldn't count because I spent so much time covering my eyes—and each time, I continue to discover new things. There's something powerfully honest about a movie that examines how the marginalized can internalize and identify with society's hatred of them.

The Final Metamorphosis

|

| "Few things are sadder than the truly monstrous." Nathanael West - The Day of the Locust -1939 |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

For a film about an actress, set in Hollywood (filmed in France) and exploring the pressures placed on women to be perfect, I appreciate how Coralie Fargeat and her team utilize a visual storytelling style that has the viewer perpetually processing this new story (The Angry Young Woman has yet to become a trope, but I think it might be on its way) through the echo of familiar cinematic imagery.

The power of images is immense, which is why it's crucial to ask ourselves who is behind the representations we see of ourselves in movies, TV, and advertising. If those controlling what we see are also the people who hate us, then their only vested interest is in teaching us how to hate ourselves.

|

| The obsession with perfection is the core theme of both The Substance and Darren Aronofsky's Black Swan |

|

| The Substance and Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey Grids and Richard Strauss' " Thus Spake Zarathustra feature in both films |

These bold callbacks to Kubrick's The Shining heighten The Substance's use

of confined spaces to create tension and convey a sense of imminent violence.

This is a two-hander as far as I'm concerned, with both Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley delivering full-throttle, pull-out-the-stops performances that are each unimaginable without the other. Qualley is new to me, but she had me in her pocket in the silent scene where Sue comes upon an indented easy chair and TV remote- evidence that Elisabeth has been wasting her allotted time doing nothing but watching television. The acute level of disapproving judgment and disgust that comes across Qualley's face at this moment speaks volumes about her character. I don't know how she did it.

|

| American Beauty / Black Dahlia |

I have to confess I'm not the best Demi Moore fan. I checked on IMDB to see how many of her films I'd seen...grand total: five (my favorite being Mortal Thoughts -1991). Before The Substance, I had not seen Moore in a movie since the 2007 Kevin Costner thriller Mr. Brooks, and I hadn't even REMEMBERED she was in it!

Moore came back into my awareness when a relative gifted me her 2019 memoir (which I initially met with a WTF? but it turns out the book is really terrific). And then, last year, she turned in a brief but powerful performance in the FX series FEUD: Capote vs. The Swans. And I was besotted.

|

| "You got it!" |

In a largely silent role, Moore is wonderfully expressive in conveying everything that Elisabeth feels and experiences. Much like what I've always admired about Julie Christie, Moore meets the challenge of giving an essentially superficial character enough depth for us to relate to and empathize with.

BONUS MATERIAL

Reality + (2014)

In this early short film by Coralie Fargeat, she touches upon many of the same themes

|

| Revenge (2017) Coralie Fargeat made her feature film directing debut with this action thriller starring Matilda Lutz and Kevin Janssens |

Jurassic Fitness

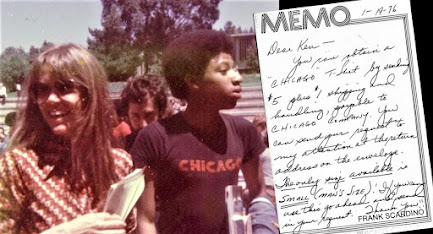

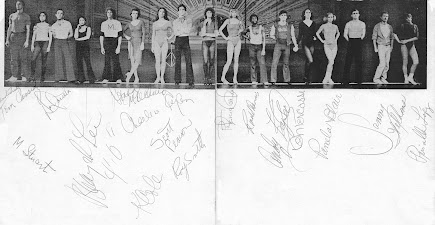

Having enjoyed a long career in the fitness industry myself (1985 to 2019), I absolutely loved that Elisabeth Sparkle was an aerobics instructor! That brief "Sparkle Your Life with Elizabeth" sequence was like watching my past flash before my eyes. Every move executed in her class was one I'd done thousands of times. Even the toxic inspirational /abusive language rings true - "Think of those bikini bods! You wanna look like a giant jellyfish on the beach?"The photo on the right is an outtake from a mercifully unproduced step-aerobics video project.

As a group instructor and personal trainer, I was pretty much immersed in a world that feeds on and perpetuates everything that The Substance is about (explaining in part why this movie so resonated with me). The promotion of oppressive beauty standards has always been a part of our culture, but the kind of perfectionist extremes The Substance speaks to have their roots in the "exercising for the aesthetics" trend of '80s fitness culture.

In fact, that tiny figure in the far right side of the movie screencap at the bottom is me working as an extra in the 1985 John Travolta/Jamie Lee Curtis aerobics exercise opus called...you guessed it, "Perfect."

|

| Sue's "Pump It Up" exercise TV program is satirically over-the-top, but from 1980 to 1982, the cable network Showtime ran a truly hilariously overheated "erotic exercise" program called "Aerobicise" that makes Sue's show look like a documentary. There's a YouTube channel devoted to it HERE. |

Take Care of Yourself

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)