West Side Story is the first movie I ever OD’d on.

It was my first pre-teen movie crush, my first filmic fateful attraction, my first case of movie musical mania. I saw West Side Story when I was in early adolescence and fell for it with the kind of overawed intensity and enthusiasm only the very young and impressionable have the time and stamina to sustain.

I was so overwhelmed by the film's soaring music, glorious dancing, and striking visual style, I embarked on a decades-long campaign of self-inflicted West Side Story oversaturation so immersive that I ended up overdosing on it. Over the course of 35 years, I saw and listened to West Side Story so often and on so many different occasions (it was my go-to "comfort food" movie) that I ultimately reached a stage where I couldn’t stand to watch it even one more time.

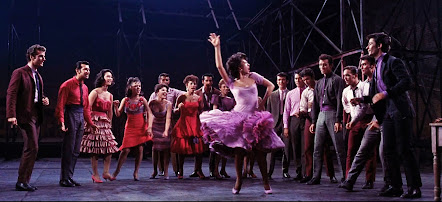

|

| The Sharks |

The last time I saw West Side Story in its entirety was way back in 2003 when the Special Collector’s Edition DVD boxed set was released. I think I watched it then about three or four times before finally hitting a wall.

But here I am in 2021, the year marking West Side Story’s 60th Anniversary, the death of Broadway legend Stephen Sondheim (WSS’s lyricist), and the release of Steven Spielberg’s long-delayed, eagerly-anticipated reimagining of the iconic film. No better time for me to fall off the wagon, acquire West Side Story in yet another home entertainment format (VHS to Blu-ray), and revisit the 1961 classic before my initial thoughts and memories risk becoming entwined, influenced, and shaped by comparisons and reactions to the latest adaptation.

|

| The Jets |

The groundbreaking musical West Side Story—the show that introduced the world to dancing street gangs and balletic inner-city combat—premiered on Broadway on September 6, 1957. Conceived, directed & choreographed by Jerome Robbins, this seminal theatrical production was a reimagining of Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet as a contemporary star-crossed love story set against the violent backdrop of turf wars and racial conflict between rival New York street gangs. With a book by Arthur Laurents, music by Leonard Bernstein, and lyrics by 27-year-old Oscar Hammerstein protégé Stephen Sondheim (his Broadway debut), West Side Story was a groundbreaking innovation in the advancement of the realistic musical. A gritty fusion of ballet and operatic romantic tragedy in a production that moved ensemble dance to the forefront.

Although I was around when all of that was playing out (I was born roughly two weeks after West Side Story opened on Broadway), I was just four years old when the much-heralded Jerome Robbins-Robert Wise co-directed feature film was released, so I have no memory at all of what a big deal it must have been at the time. I don't even know if my parents went to see it.

In trying to recall when I first became aware of West Side Story, my earliest memory places me at about six or seven years old and the West Side Story original Broadway cast album being one of a couple of unopened LPs in my parent's record collection (in the days of mail-order record clubs that automatically sent members a monthly featured LP unless a "decline" card was mailed in time, it was quite common for families to have a couple of albums they just weren't interested in but couldn't bother to send back).

As for me, I, too, ignored the West Side Story OBC album, my six-year-old sensibilities accurately gleaning from its cover art that it contained no songs to which I could do The Twist.

|

| Natalie Wood as Maria |

|

| Richard Beymer as Tony |

The opportunity to see West Side Story for the first time came in the fall of 1968 when the 10-time Oscar-winning film was given a national re-release before being sold to television (and to coincide with/cash-in-on the October 1968 release of Franco Zeffirelli's Romeo and Juliet). I was then 11 years old and remember West Side Story was playing at our neighborhood movie house (the Castro Theater in San Francisco) for a single one-week engagement during the Thanksgiving holiday. In a rare gesture inspired, I suspect, by the theater’s close proximity and the prolonged underfoot proximity of a bunch of restless kids at home on Thanksgiving break, my parents decided to treat us all (me and my three sisters) to a rare family night out at the movies.

|

| Rita Moreno as Anita |

|

| George Chakiris as Bernardo |

Going to the movies at night with my parents always felt like a big event and a little magical to me. For one, we all had to get dressed up. Plus, it was nice going by warm car instead of walking or having to catch a bus. But my favorite thing, and what really made going to the movies at night feel magical was the bright neon and colored lights of the theater marquee and lobby. As often as we kids had attended screenings at the Castro on weekend afternoons, the familiarly ornate theater looked totally different at night. More like a palace or castle. With parents along, we didn't have to ration out our allowance money for popcorn and candy, and best of all, we got the major thrill of being able to sit in the balcony. A place our parents had forbidden us to go when we were on our own because—according to mom—the balcony is where all the troublemaking kids sat.

|

| Russ Tamblyn as Riff |

While I was overjoyed to be going to the movies that night, I don’t recall being particularly enthusiastic about seeing West Side Story. I still didn't know much about it, and what little I did (shots of Natalie Wood & Richard Beymer clinging to each other with their mouths open on a fire escape) didn't suggest a whole lot of laughs. But having gone to see Peter Sellers several times in Casino Royale (1967) earlier that year and later in The World of Henry Orient (1964) on TV, the movie I was most excited about seeing was the one the Castro paired with West Side Story on a double-bill: Blake Edwards' The Party (1968) - in which Peter Sellers plays an Indian actor who comically destroys a Hollywood party.

Screened first, I loved The Party and think it's one of Sellers' best. However, looking back, I have to say that was one weird double-feature: Welcome to four full hours of ethnic cosplay and brownface!

(On a side note: the movie booked to follow West Side Story’s one-week engagement at the Castro was Rosemary’s Baby. So being traumatized by that film's spooky theatrical trailer was another memory I took away with me that evening.)

The 1968 West Side Story re-release was shown minus the overture and intermission of its 1961 roadshow engagements, but it was presented in breathtaking widescreen (a welcome change from our 20-inch B&W console TV), eye-popping color (growing up seeing 95% of all entertainments in grayscale, a bigger thrill than you might think), and with stereo sound that fairly lifted me out of my seat. But none of these things would have mattered if the film they buttressed hadn’t measured up to the fanfare. And on that score, West Side Story fairly blew the roof off the Castro Theater that night.

A phenomenal film experience, West Side Story was like nothing I’d ever seen (granted, at 11, the list of things I'd never seen was pretty extensive, but you get my point). I couldn't think of any movies I'd seen that looked even remotely like West Side Story. From that astounding 8-minute Prologue that sets the stage and establishes the film's stylized realism and visual vocabulary of saturated colors, to the vivid elegance of its cinematography and evocative use of music, it was obvious from West Side Story's jaw-dropping first frames (those aerial views of New York!) that it was a breed apart from the kind of musicals being turned into films at the time (Bells Are Ringing, Flower Drum Song, The Music Man). Even its innovative score…classical, operatic, jazzy...one unforgettable song after another--didn’t sound much like the other musicals (Bye Bye Birdie, The Sound of Music).

And the dancing. Had there ever been such engagingly witty, extraordinarily exhilarating dance sequences? Electrifying ensemble dance numbers that were genuine showstoppers, not because of empty spectacle, but because dance, music, cinematography, and editing were in simultaneous, seamless service to character, emotion, and the dramatic flow of the narrative. In the large-scale numbers, every dancer is doing more than dancing...they're acting, they're revealing character, they're giving a performance. There's so much detail to take in and so much "business" going on in every corner of the frame, it feels like this 1961 movie was made for the digital age of the freeze-frame. To watch the way Rita Moreno and George Chakiris look at each other when they dance is to learn everything you need to know about the relationship between Anita and Bernardo.

I’ve recounted in earlier essays how averse to age-appropriate movies I was when I was young. That's how I missed out on seeing Funny Girl, The Sound of Music, and Mary Poppins...I thought they were all "kiddie movies" or worse, movies deemed “fun for the whole family.” West Side Story won my heart in no small part due to it being a grown-up musical. Grown-up by ‘60s movie musical standards, anyway. The film was pretty dated and tame in some ways. I mean, the Jets—direct descendants of The Bowery Boys and Dead End Kids who pronounced “world” as “woild” and spoke in the colorful bop-slang patois of those low-budget ‘50s juvenile delinquent movies my sisters and I devoured on Saturday afternoon TV (“Daddy-o!”)—were harmless hoodlums. (The Jets' cartoonishness had the perhaps intentional effect of softening the distastefulness of their "Make The West Side Great Again" racism.)

But this was also a movie, a musical, no less, that was critical of what was wrong with American society and referenced mature themes like racism, drugs, poverty, gang violence, prostitution, rape, and police corruption. It even had good-girl Natalie Wood having sex without benefit of marriage (although I admit, at the time, I thought Maria and Tony had just spent the night cuddling).

|

| The Delicate Delinquent |

Speaking of things I'd never seen before, gay Ken, whom I hadn't yet been properly introduced to, never saw ANYTHING like George Chakiris. I don’t quite know what I did with the feelings aroused by the sight of Bernardo in that purple shirt and skinny tie, but I suspect they were tucked away in the same place I put my unconscious identification with/recognition of the queer-coded character of Baby John.

(Ask Anybodys: For those who don't know, the creators of West Side Story - Laurents, Bernstein, Sondheim, and Robbins - were all gay or bisexual men in various stages of closeted/denial. Too bad at least one of them wasn't also Puerto Rican.)

|

| Somewhere As the song that best expresses what co-creator Arthur Laurents described as West Side Story's theme: "How can love survive in a violent world of prejudice?" --Somewhere has gone on to become a pop standard and a gay anthem. The latter confirmed when The Pet Shop Boys reworked it into a synth-pop dance tune. |

My earlier use of the word "dated" wasn't intended as a pejorative. As it relates to my impression of West Side Story as a product of the past, a film reflecting the perspective, aesthetics, and concerns (and occasional cluelessness) of a very distinct point in time, I see it as one of West Side Story's strengths. The same way I would mean it if I referred to the films of Fred Astaire and many of the classic MGM musicals as dated. They are of the time they were created and reflect a kind of past urgency or vitality that can't be wrested into another era.

West Side Story being behind-the-times in some aspects (while simultaneously raising and setting the bar of innovation in others) lends the film an air of parable or fairy tale. Its themes are rooted in realism, but the world depicted is very different from reality.

The world had changed a great deal between the time West Side Story first appeared on screens and the time I saw it. It wasn't a seven-year gap, it was a lifetime. Even as a kid I thought the film's depiction of a world where restless youths (just how the hell old ARE the Jets and Sharks supposed to be?) blew off steam by having turf wars and zip-gun rumbles seemed as remote as Neverland when contrasted with the what young people were dealing with in 1968: Two political assassinations in 1968 alone, race riots, the Vietnam War, police brutality, campus protests.

Yet the film still spoke to me. And I think that's because the things it talks about (even in its clumsy '50s jargon) are still real for young people. And it has been since the days of Romeo and Juliet.

Looking back, I feel so lucky to have seen West Side Story for the first time with no idea of its significance, no sense of its legacy, and no prior exposure to its music (I HAD heard the lilting "I Feel Pretty" on some variety show, and was so surprised to learn it came from this show). I’ve never forgotten what it was like experiencing this innovative, visually dazzling, and highly entertaining musical as a journey of complete discovery. I was taken on a real emotional roller coaster that night, from the ecstasy heights of those fabulous numbers to that ending that gave me major waterworks (I think you always cry harder in movies if you see your mom is crying, too), everything came together so beautifully. West Side Story was without a doubt a most extraordinary movie experience.

I Saw You and The World Went Away

West Side Story remained an ongoing passion and fan favorite for lo these many years. The visual aid purpose of this collage is to show not only how much fun I had being a West Side Story fan, but also illustrate how I came to reach such an oversaturation point. And if you're wondering about that TV Guide ad at the bottom that has nothing to do with West Side Story, let me put it this way... there's a reason I say dreams are what the cinema is for.

The year 1985 (five years after the movie Xanadu inspired me to study dance) found me on a cordoned-off city block in Los Angeles--folks watching from behind barriers, massive speakers blaring musical playback, a camera on a crane---dancing as a member of a terpsichorean street gang in a West Side Story-inspired musical fantasy sequence for a CBS Schoolbreak Special: Ace Hits the Big Time.

The hilariously cheesy number was more nightmare than dream sequence, and my dancing in it didn't give George Chakiris any sleepless nights, but for that entire day, I felt as though it wasn't really happening...that it was all a fantasy playing out in the head of 11-year-old Ken sitting in the balcony of the Castro movie theater.

Gee, Officer Krupke

|

| Always thought Russ Tamblyn deserved an Oscar or Golden Globe nomination |

|

| Nobody does a flip-out like Natalie Wood. I really adore her in this movie, and she's at her strongest in this scene. The way she yells "Don't you touch him!" is heart-wrenching. Cue the waterworks. |

WEST SIDE STORY INFLUENCE & INSPIRATION

(Top - Tony Mordente as Action). This quotable admonition, in addition to the Jets' stare-down, finger-snapping response to authority figures, found its way into the 1967 teen musical The Cool Ones, choreographed by a student of West Side Story's David Winters (A-rab)...one Toni Basil.

Critics couldn't make up their minds as to whether Bob Fosse's rooftop staging of "There's Gotta Be Something Better Than This" in Sweet Charity was a skirt-flipping homage or blatant rip-off. The same with his decision to stage the "Rhythm of Life" number in a subterranean parking structure (a la West Side Story's "Cool").

It's not unusual for artists to be unfamiliar with the trailblazers and innovators in their field. Indeed, in many cases, ignorance behooves the young artist, lest they find out their trumpeted originality is often just history repeating (see: Lady Gaga, Bette Midler, and a singing mermaid named Delores DeLago).

But director Bob Giraldi's persistent claim that his music video for Beat It (featuring dancing rival street gangs - complete with singer-snaps and a choreographed rumble) was not influenced by West Side Story is both laughably unconvincing and blatantly disingenuous. And (the most likely option) the kind of cagey deception one engages in to sidestep potential legal hassles.

In any event, Rita Moreno once relayed in an interview how Michael Jackson approached her at a social function and proclaimed to be such a huge West Side Story fan that the film inspired the song, concept, and choreography of the music video.

|

| Premiere at Grauman's Chinese Theater on Wednesday, December 13, 1961. A week earlier, on December 5th, Natalie Wood had her footprints placed in the cement in the theater's forecourt. |

Video Clip - Dance at the Gym / Mambo

BONUS MATERIAL

|

| Womb to Tomb Former Jets Russ Tamblyn and Richard Beymer appeared in the David Lynch series Twin Peaks in 1990 and its 2017 return. |

I promised myself that I wasn't going to post this somewhat overworked image, but I have to concede that there's a very good reason for its popularity. The tenement backdrop, the natural light, the low camera angle (accomplished by digging a pit in the asphalt), and the graceful athleticism of the dancers as they execute a grand battement à la seconde in relevé...is pure visual poetry. With their faces lifted to the sun and their bodies literally rising above their gritty reality, this image perfectly captures the aspirational spirit that is the essence of West Side Story's "Somewhere."

.JPG)

.JPG)