"We only pass this way once; might as well pass by in a Cadillac."

Two years before Robert Altman’s Nashville (1975) gave us an epic vision of America viewed through the “politics is show-biz” prism of the Country & Western music scene, Canadian television producer/director Daryl Duke (The Silent Partner -1978) and novelist Don Carpenter (Hard Rain Falling - 1966) made their collective feature film debuts with the audacious indie character-study Payday.

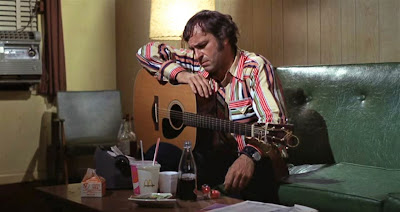

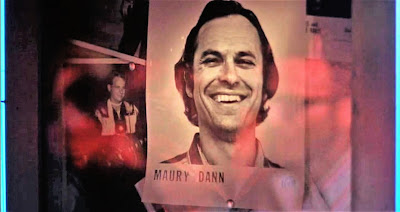

Chronicling 36 full-throttle hours in the life of hell-raising, second-tier country music star Maury Dann (Rip Torn), the focus of Payday’s lens may be narrower than Nashville’s, but in its depiction of the squalid glamour of an entertainer’s life on the road—fast money, fast food, & fast-living—it provides a picture of '70s American culture that is no less funny, raw, or keenly-observed. And thanks to Torn's career-best performance, it feels considerably more authentic. For this road-movie odyssey (described by one critic as “A study in amorality without a moral”), Duke and Carpenter have devised a wittily apt visual metaphor for Nixon-era America: an all-white Cadillac speeding heedlessly along a highway at 95 miles an hour on a path predetermined to be the road to success, but is just as likely a collision course headed straightaway to a dead-end.

|

| Rip Torn as Maury Dann |

|

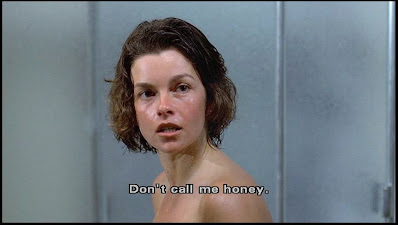

| Ahna Capri as Mayleen Travis |

|

| Michael C. Gwynne as Clarence McGinty |

|

| Elayne Heilveil as Rosamund McClintock |

|

| Cliff Emmich as Chicago |

Imagine a Nashville sequel that abandons the ensemble format and instead focuses entirely on Keith Carradine’s callous, womanizing balladeer, Tom Frank—his future, burn-out years—and you’ve got a pretty good idea of what Payday is like.

Maury Dann is a 35-year-old country-western singer/songwriter who’s achieved an appreciable degree of success in his career (his face recognizable enough to get him out of speeding tickets, his name drawing sizable crowds and an unbroken chain of disposable, star-struck groupies to his roadhouse gigs); but he’s nonetheless driven just a little bit crazy by his so-close-you-can-almost-touch-it proximity to the " big time."

A growly crooner of shrewdly sincere songs of homespun virtues, the oilily charismatic Dann...a toxic combination of hard-working and hard-living…tours the one-night-stand honkytonk circuit of the Deep South in his chauffeured, cowhide-interior Cadillac, girlfriend-of-the-moment in tow, subsisting on pot, pills, booze, junk food, and sex. More savvy businessman than impassioned artist, Dann is not without talent. But ambition, greed, and a love of the perks of privilege have him living not for the artistic expression but for the payday. And it’s not difficult to understand why.

|

| Maury Dann & the Dandies |

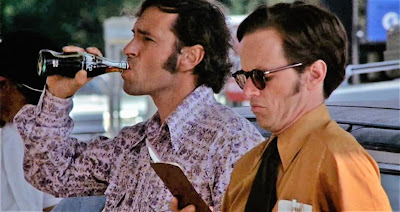

Cocooned from both truth and consequences by a small but selflessly loyal entourage of enablers, Dann’s fame and wealth afford him both the means and wherewithal to support his ex-wife and three children (whose ages he can’t keep straight) while providing his pill-popping mother with ample supplies of amphetamines. All with plenty left over for payola payouts to influential disc jockeys and buying himself out of the numerous scrapes his hair-trigger temper and violent mood swings get him into.

Payday kicks off with Dann already three months into his breakneck tour. He is in Alabama, heading for Nashville, where the success he desperately seeks beckons in the form of a vaguely promised appearance on Johnny Cash’s TV special (Dann bitterly hints that he and Cash have been kicking around for roughly the same amount of time). The goal is clear, but the challenge faced is whether or not Maury Dann can steer clear of self-destruct mode long enough to make it.

Were someone to ask me what I like so much about ‘70s films and what I think distinguishes them from motion pictures made in any other era, I would point to Payday as a film representative of precisely those inarticulable qualities I love so much, gravitate to, and often only find in the movies made during the New Hollywood years. What I mean is that I like when a movie feels as though it were made because the filmmaker had a story they wanted to tell, not because of market research, the desire to make a mint, or as a result of lawyers fashioning a "package" out of the merging of mutual advantage contracts.

Payday suffered at the boxoffice because it didn't fit into any particular genre, and its distributor couldn't find a way to properly market it.

|

| Henry O. Arnold as Ted Blankenship A former waiter and longtime Maury Dann fan who aspires to be a songwriter |

With so many of today's movies being greenlit only after their market viability has been analyzed to the nth degree, my perhaps rose-colored nostalgia for the '70s stems from the number of unique, personal, difficult-to-categorize, and downright weird movies that came out of that era.

That being said, how is it then that I only got around to seeing Payday for the first time just a couple of years ago?

I remember when Payday came out in 1973. It was one of a spate of intimate, personal films released during the Vietnam/Nixon years that sought to challenge Hollywood’s outsized and outdated “mythic hero” tradition by training its lens on the small, often ineffectual lives of ordinary people (Kansas City Bomber, The Last American Hero, Play it As it Lays, Electra Glide in Blue).

|

| Jeff Morris as Bob Talley, a member of Maury Dann's band Actor Jeff Morris would play another country boy named Bob in 1980s The Blues Brothers - proprietor of the roadhouse Bob's Country Bunker |

Payday--whose newspaper ads targeted the arthouse crowd in urban markets while (misleadingly) pitching itself as a Burt Reynolds-style redneck romp in rural districts--received laudatory reviews on its release, was selected to be shown out of competition at the Cannes Film Festival, and at the end of the year, appeared on many critics' Ten Best lists. Yet despite bearing all the potential earmarks of becoming a sleeper hit or "critic's darling" underdog of the award season, nominations were not forthcoming, audiences stayed away in droves, and Payday wound up disappearing from theaters faster than a knife fight in a phone booth. (Just keepin' in the spirit of things.)

Why didn’t I see it? Well, for one, there were considerably bigger cinema fish for this teenage movie buff to fry in '73: The Exorcist, The Last of Sheila, Jesus Christ Superstar, The Way We Were, Lost Horizon. Second, not only did the idea of a movie set in the world of country music fail to grab me (it would take Nashville to kickstart my love of country music), but I didn’t know anything about its director, and the only person in the cast I’d ever heard of was Rip Torn. And what little I’d seen of him in supporting roles in Sweet Bird of Youth (1962) and You’re A Big Boy Now (1966) was impressive, but not enough to convince me that seeing Payday was a better weekend option than going to see The Poseidon Adventure for the fifth time.

|

| On the Road Again Dann and his ever-busy road manager, McGinty |

Of course, after finally seeing Payday (three times, so far), I truly regret having missed out on the opportunity to see it on the big screen. And I wonder how seeing it would have impacted my experience of Nashville two years later. Payday impressed me with the way it manages to be so familiar (A Face in the Crowd, The Rose, I Saw The Light: The Story of Hank Williams), yet via its fleshed-out characterizations and insightful script, managed to catch me totally off guard. Narratively, nothing went where I expected. I know my 15-year-old self would have been thoroughly enraptured by it all. I think Payday is one of the best films of 1973, and Rip Torn was robbed of a Best Actor Oscar nomination (especially when I think of Robert Redford's "department store mannequin" performance in The Sting clogging up the category that year).

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

Out of a naïve-but-purposeful desire to be in a music star’s orbit, a central character in Payday allows herself to be swept up in the counterfeit glamour of Maury Dann’s chaos-addiction lifestyle, whisked away in his Cadillac headed for god-knows-where…without money, a change of clothes, or alerting the 5 and Dime where her cashier services are anticipated the following day.

Watching Payday for the first time felt a little like that.

Payday unfolds in a non-stop, barely-time-to-catch-your-breath style ideally suited to the subject matter. It's shot in an intimate, almost documentary style that makes the viewer feel as though gifted the best seats in the house to see a country western star at his best (I’m crazy about Rip Torn’s voice! It’s not good, but it’s right), only to find oneself the unwitting witnesses to the up close and personal spectacle of a dishonorable man’s disintegration.

|

| Maury Dann - Living for the Payday |

McGinty - (referring to roadhouse owner) He wants a piece of the gate next time out.

Dann - People in hell want ice water, too.

Like its lead character, Payday hits the ground running and sweeps the viewer up in the garish allure (or morbid curiosity) of its authentically-rendered backstage view of life on the road. A world of grungy motel rooms with wood-paneled walls and chenille bedspreads that play host to after-hours poker parties, informal business meetings, impromptu jam sessions, and drunken sexual assaults cloaked in fame entitlement and groupie expectation. Rooms littered with beer cans, Jack Daniels bottles, cigar butts, Hardee’s cups, and fast-food wrappers. Capturing the isolated, on-the-move, “what town are we in?” feeling of being on tour, Payday depicts Dann’s life as an episodic string of personality-revealing vignettes. A kind of road odyssey of self-confrontation headed down the road toward the inevitable day of reckoning.

|

| MEETING IN THE LADIES' ROOM Girlfriend #1 confronts potential girlfriend #2 |

Most movies set in the music industry are about performers unable to handle their success. What eats at Maury Dann is the far more relatable knot of resentment he harbors for not having achieved the kind of success he feels he deserves. Indeed, one senses that behind Dann’s manic restlessness, quick-trigger temper, and hell-raising antics is a man terrified of what he would have to look at if he just stood still for a minute. As the film's late director states on the DVD commentary, if Dann ever stopped moving, he'd be forced to confront the fact that he's a failure. Certainly, a failure as a husband and a father and as a human being...but also in failing to achieve the stardom that's obviously so important to him. Realizing that it will forever be out of his reach, fading further into the distance with each passing year.

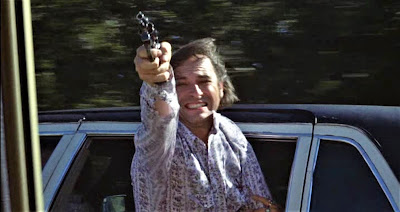

Just a liquored-up good ol' boy firing a gun out the window of a speeding car for fun

Like all malignant narcissists, Maury Dann goes through life

challenging fate with the dare: What can't I get away with?

Though my love for dark-themed movies is clear and well-chronicled, I nevertheless understand that most people, when faced with a movie whose main character is a lout and a heel, ask why they would want to spend time in the celluloid company of someone they’d cross the street to avoid in real life.

|

| Eleanor Fell as Galen Dann Maury's ex-wife and mother to Billy, Kitty, and Elmore (Rip Torn's real name) |

But the anti-hero trend in ‘70s films was always less about liking or even relating to the character in question; it was about confronting the "hero" myths our culture has bought into, and examining the lies we construct and tell ourselves via our "traditional" screen idols. The purpose served by the heroes of mainstream films was to perpetuate myths of honor and valor that flattered the audience's image of itself. Hollywood in the '70s continued to lean into metaphorically simple concepts of evil and heroism: villains wore black hats, good guys were white, heteronormative males in the John Wayne tradition.

But the '70s reality is the same as it is today...the real villains don't wear black hats. They look like the people we had been taught to put our trust in and/or look up to: the politicians, the powerful businessmen, the police, the celebrities, the military, and the clergy. The '70s anti-hero...a by-product of the betrayals of Vietnam and Watergate, sought to make us look at the dark side of American myth and the traditional hero--in this instance, the country-western singer who hawks Heartland homilies and family-values hokum--and in doing so, explore the dark side of ourselves as a society and a country.

|

| Striking a Deal with the Devil If you're famous and rich in America, there's no moral bottom you can hit that cannot be forgiven, enabled, or covered up |

In Payday, Maury Dann is America. Or rather, those hypocritical aspects of American culture that seem to produce, reward, and encourage the Maury Dann’s of the world while simultaneously lying to itself about the supposed value it places in simpler virtues.

In Dann's relentless pursuit of money, fame, and the privilege perks of same (aka power) are written the very tenets of America's success ethic. Does it matter that in the achievement of these things, Dann has become a cruel and remorseless monster? Not likely. For Dann has learned--like most politicians, religious "leaders," and pop-culture celebrities--that for a public that loves to be lied to, having the appearance of being principled and moral is far more important than actually being those things.

It strikes me as both purposeful and perfect that Payday is set in the world of country music. As a genre that has long aligned itself with (and exploited) the so-called Christian, blue-collar, America's heartland, family values myth, it serves as the perfect illustrative metaphor exposing how America's persistent lies to itself have become its truth. The ethics of country singers are no more resistant to the usual temptations and corruptions of wealth and fame. In fact, their tendency to cloak themselves in the flag, the Bible, and those ever-illusory, gun-totin' "family values" likely makes them more susceptible to the sins of duplicity and hypocrisy.

|

| Sex, Drugs, and Country & Western |

PERFORMANCES

Rip Torn’s raw, lived-in performance is the electrifying core of Payday. Bringing a homegrown gravitas to the character, Torn’s is the type of bravura screen performance given by an actor finally granted a role on scale with his talents (Don Carpenter wrote it with Torn in mind, and it’s hard to imagine anyone else in the role). He's positively riveting. And though it sounds like just the kind of quote-ready critical assessment that movie publicity departments pray for, I genuinely think Rip Torn's performance in Payday is one of the best American screen performances of the '70s.

Adding considerable support is Ahna Capri as Dann’s vigilant girlfriend, whose continued, hawk-eyed efforts to guard her interests are both amusing and reminded me of a pragmatic, more resilient version of Ann-Margret’s Bobbie Templeton in Carnal Knowledge. Elayne Heilveil, Michael Gwynne, and Cliff Emmich also gave very strong performances.

Clip from "Payday" 1973

BONUS MATERIAL

Four of the original country songs in Payday’s soundtrack were written by the late, great Shel Silverstein: playwright, poet, cartoonist, author, and Grammy Award-winning songwriter (1969 Best Country Song “A Boy Named Sue”). Payday showcases the Silverstein compositions - “Slowly Fading Circle," “Baby, Here’s a Dime,” and “Lovin’ You More” (whose chorus “I’m lovin’ you more but you’re enjoying it less” is [for those too young to take notice] a comic takeoff on the 1960’s Camel cigarettes ad slogan “Are you smoking more but enjoying it less?”).

My personal favorite is “She's Only a Country Girl,” a catchy, drawling, earworm of a song that got stuck in my head for days after seeing this. It sounds like a song Henry Gibson's Haven Hamilton might have sung in Nashville.

Payday features three more songs by different composers: “Road to Nashville”, “Flatland”, and “Payday” - leaving me wishing the film had been met with a little more success and produced a soundtrack album.