When most people think of cinema in the '70s, they think of a

time of innovation, upheaval, and experimentation. And indeed, it was. But the '70s was also the decade that introduced the first generation of film-weaned

filmmakers. The directors, producers, and writers who grew up watching movies.

Wholly uninterested in the experimental exploration of film's

potential as an art form or means of creative expression, this new breed of nostalgia-prone, rear-view-fixated

filmmakers—many of them former movie critics or film scholars—not only seemed to have spent the entirety of their formative years in front of movie screens (suggesting, perhaps, a lack of actual, real-life-acquired insights to impart in their work beyond those

gleaned, secondhand, from movies); but when granted the opportunity to make films of their own, strove for no ambition

loftier than to remake, revisit, and re-imagine the movies that meant so much to

them while growing up.

The legacy of such willfully arrested artistic development in today's Hollywood can most certainly be seen in the industry's worrisome over-reliance on remakes and

reboots and the almost-surreal global dominance of mega-budget, adolescence-coddling

comic book superhero movies. But back in the day of the Auteur Theory, Nouvelle

Vague, and the New Hollywood, the regressive filmmaker was primarily dismissed by so-called serious cineastes. Luckily for these filmmakers, they were taken to the bosom of a moviegoing public growing weary of avant-garde filmmaking techniques, artsy pretensions, and non-linear storytelling. Indeed, in the wake of the '70s oil crisis,

inflation, Vietnam, and Watergate, many audiences found the notion of escaping into the romanticized idealization of the past to be a very appealing proposition.

Some directors, like François Truffaut, paid homage to the

filmmakers they admired (Hitchcock, in his case) by reinterpreting that director's style through a

modern prism. Others, like Francis Ford Coppola, found fame by applying auteurist theories to classicist filmmaking. Only Peter

Bogdanovich—actor, film scholar, and critic—drew the ire of Hollywood

Renaissance movie cultists (while gaining success as the Golden Boy of the nostalgia craze) by making new "old"

movies.

|

| Ryan O'Neal as Moses (Moze) Pray |

|

| Tatum O'Neal as Addie Loggins |

|

| Madeline Kahn as Miss Trixie Delight (alias, Mademoiselle) |

|

| P.J. Johnson as Imogene |

|

| Burton Gilliam as Floyd |

.JPG) |

| John Hillerman as Deputy Hardin / Jess Hardin |

|

| Randy Quaid as Leroy |

Although Peter Bogdanovich is technically credited with

being its director, Paper Moon, like its

predecessors The Last Picture Show (1971)

and What's Up, Doc? (1972), is a film

so heavily influenced by Howard Hawks, John Ford, and Orson Welles, each

gentleman, by rights, could share co-director billing. A point Bogdanovich himself

would likely make no bones about, for on the DVD commentary, he states, "The movie was very 1935 with '70s actors." And to be sure, what with the film's salty

language, racy humor, and a pint-sized, cigarette-smoking heroine so cheeky she'd

take the curl out of Shirley Temple's hair; Paper

Moon feels very much like some kind of pre-Code Preston Sturges movie shot

through with a dose of '70s self-awareness.

Paper Moon, a Depression-era

road comedy skillfully and hilariously adapted by Alvin Sargent (The Sterile Cuckoo) from Joe David

Brown's 1971 novel Addie Pray, is the

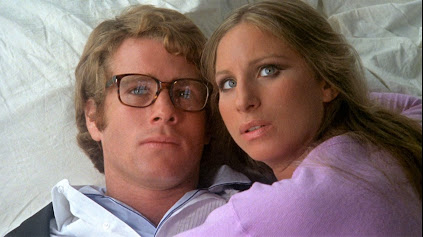

story of small-time con man Moses Pray (Ryan O'Neal), who meets his match in

little Addie Loggins (Ryan's real-life daughter, Tatum O'Neal), an old-beyond-her-8-years,

recently-orphaned waif who may or may

not be his illegitimate daughter. Entrusted with escorting the child from

Kansas to Missouri to stay with relatives, Moze's attempt to first swindle, then

unburden himself of the cagey tyke results in the tables being turned on him

in a manner ultimately binding the two as reluctant partners in cross-country

flim-flams. The quarrelsome duo's misadventures swindling widows, bilking shopkeepers,

and taking up with buxom carnival dancer Trixie Delight (Kahn) and her beleaguered

maid, Imogene (Johnson), are played out against a bleak Midwestern landscape of

barren skies and vast Kansas plains redolent of The Grapes of Wrath.

Gloriously shot, cleverly conceived, superbly acted, and consistently laugh-out-loud funny, Paper Moon is a feast of period detail and sharp comedy writing that manages to be sweetly sentimental without veering into the saccharine. And while I find the film to be a little draggy in its third act (perhaps because things take a darker turn), the first two-thirds of Paper Moon is very nearly perfect.

Following a tight, 3-act structure, Paper Moon, with the introduction of Trixie and Imogene to the narrative in the second act, reaches such a giddy height of comedy incandescence that the film never fully regains its footing once they depart. These characters bring so much variance to the interplay of Moze and Addie that when nothing is there to take its place but a sinister bootlegger and a fistfighting hillbilly, one can almost feel the air leaving the movie. Almost. The O'Neal chemistry is too strong to let the film flounder completely.

|

| The Only Time We See Addie's Mother (and we understand why Addie is so attached to that cloche hat) |

If it can be said of Bogdanovich that he is a director who has spent his life forever at the feet of The Masters, then at least he's a student who learned his lessons well. For as with all of his early films, Paper Moon reveals Bogdanovich to be a deft and sensitive storyteller, versatile and fluent in the language of cinema. He understands what he's doing, knows what he's going for, and, despite a film-geek tendency toward stylistic imitation-as-flattery, has an inspired touch when it comes to comedy. Rare among nostalgists, Bogdanovich has a talent for making the familiar feel engagingly fresh.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

Paper Moon is one

of my favorite comedies, one I've always regretted never having seen at a theater

in the presence of an audience. But as I recount in an earlier post on this blog about The Last Picture Show, as a young man, I was

less than enthralled by the whole '70s nostalgia craze:

"As an African-American teen inspired by the

emerging prominence of Black actors on the screen and excited about the upsurge

in positive depictions of African-American life in movies of the 70s; these

retro films, with their all-white casts and dreamy idealization of a time in America's

past which was, in all probability, a living nightmare for my parents and

grandparents, felt like a step in the wrong direction. The antennae of my

adolescent cynicism told me that all this rear-view fetishism

was just Hollywood's way of maintaining the status quo. A way of reverting back

to traditional gender and racial roles, and avoiding the unwieldy game-change

presented by the demand for more racial diversity onscreen, the evolving role

of women in society, and the increased visibility of gays."

And while I still feel this to be true and witness the same

thing happening today in Hollywood's focus on fantasy films populated with mythical

creatures, elves, gnomes, wizards, and superbeings of all stripes (anything but

those pesky, problematic people of color); the passage of time has literally transformed Paper Moon into what it was always designed

to be: an old movie. And old movies I can watch through a prism of the past I'd

otherwise find unacceptable, if not reprehensible, in a contemporary film.

If there's a method to Bogdanovich's retro madness, it's that Paper Moon is often at its funniest when it uses our familiarity with '30s movie tropes as the setup for contemporary, very '70s comic reversals. Tatum O'Neal's tough-talking Addie amuses in part because she's so very unlike the kind of little girl every parent wanted their daughter to be in the '30s: Shirley Temple. Trixie's maid, Imogene, may recall the sassy Black maids of '30s comedies, but it's her uproariously open and blatant hostility toward her employer that lays to rest the comforting stereotype of the childlike devoted domestic.

I think it was Bogdanovich who once made the observation that people of a certain age visualize the 1930s in their mind's eye as a black-and-white era because that's the only way they know it; through black-and-white-photos, black-and-white movies. When Paper Moon, with its meticulous recreation of the look and feel of a 1935 movie (which is, importantly, not the same thing as recreating real life in 1935), has its very period-specific characters using language unthinkable in films of the day, the visual and behavioral incongruity is riotously funny.

|

| Ryan's Daughter |

PERFORMANCES

As everyone knows, 10-year-old Tatum O'Neal made history by

being the youngest person to ever win a competitive Oscar when she won Best

Supporting Actress for Paper Moon in

1974. And on that score, you'll get no argument from me. I'm really not very fond

of kids (either on or off-screen), a predisposition compounded by Hollywood's fascination with precocious

kids whose mature behavior I'm supposed to find adorable. But Bogdanovich works

a minor miracle with Tatum O'Neal. She actually IS an adorable, precocious child…sweet

of face, husky of voice, and inhabited, apparently, by the soul of a 50-year-old

grifter.

|

| Paper Moon's great, unsung asset is Ryan O'Neal. Looser and funnier than you're likely to see him in any other film, he is a real charmer with an impressive range of exasperated reactions |

Tatum O'Neal is nothing short of a marvel in a role in which she's required to play a range of emotions a seasoned professional would find challenging. And even if the rumors are true that Bogdanovich shaped every gesture, nuance, and line reading (easy enough to believe given the flatness of her subsequent performances in The Bad News Bears and International Velvet), hers is still an amazingly assured and natural performance for one so young (O'Neal was eight when filming began).

Now, with all that being said, I do have to lodge my one complaint:

there is no way in hell Addie Pray is a supporting role. It's a lead. The

entire film rests on her shoulders, and she appears in more scenes than anyone

else in the film. It's patently absurd that Tatum O'Neal was entered in the Best

Supporting Actress category.

Of course, my rant is based on my ironclad certainty that,

taking absolutely nothing from O'Neal's great performance, it was Madeline Kahn who deserved that award. As good as Paper

Moon is, my A+ rating would drop to a B-minus without Kahn's Trixie Delight. She's that good.

I'm sure someone somewhere must have tallied the length of Madeline Kahn's screen time in Paper Moon. She's not onscreen all that long, but every moment—from her memorably jiggly entrance, past her umpteenth speech extolling the virtues of bone structure, all the way to her magnificent scene on that hilltop—is sheer brilliance. That hilltop scene is one of the finest onscreen moments in Kahn's entire career. I love when an actor can make you laugh while at the same time touching upon something vulnerable and sad behind the facade.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

The off-kilter charm of Paper

Moon is in it essentially being a romantic comedy. An uneasy love story

between a father and daughter who may or may not be biologically related ("It's pothible!"). That Addie doesn't

really see herself as a little girl and Moze not seeing himself as anything closely

resembling a father, makes for several amusingly awkward scenes where the querulous

duo is forced to play-act the roles of loving father and daughter in order to perpetrate

a swindle. Scenes made all the more touching by all the other times we see them reluctant to yield to even the slightest display

of affection for one another.

|

| Two days and 36 takes (!) produced this exceptional continuous shot sequence |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Over the years, Peter Bogdanovich's unrealized potential as a director and the dysfunctional family circus that has become the O'Neals has lent a bittersweet air of nostalgia to Paper Moon that's wholly unintentional and unrelated to the film's roots in 1930s wistfulness. For years it had been hinted that Bogdanovich's success was significantly reliant upon his wife, production, and costume designer, Polly Platt. Paper Moon marks their last collaboration (they divorced after Peter fell in love with Cybill Shepherd during the making of The Last Picture Show) and, perhaps tellingly, the end of Bogdanovich's success streak. As a longtime admirer (if not idolater) of Orson Welles, it couldn't have been lost on Bogdanovich the degree to which his drop in popularity mirrored Welles' own tarnished Golden Boy career decline.

By way of talk shows, memoirs, and tabloid headlines, Ryan and Tatum O'Neal have practically built a cottage industry around airing the dirty laundry of their familial discord. Watching Paper Moon these days, one can't help but respond to the almost documentary aspects of Moze and Addie's push-pull relationship. This is especially true of scenes depicting Addie's possessiveness toward Moze and jealousy of any female attention directed towards him (Addie's relationship with Trixie is like being given front-row seats to how the whole Tatum O'Neal/Farrah Fawcett thing played out).

When I watch the classic TV show, I Love Lucy, it often crosses my mind that I'm watching a wish-fulfillment version of the real-life marriage of Lucille Ball & Desi Arnaz. In light of the painful reality we've come to know about the relationship of the O'Neals, Moze and Addie have become, for me, the idealized image of Ryan and Tatum.

As I do with Orson Welles, I always associate Peter Bogdanovich with the genius work of his early career and largely overlook his latter contributions. And while I know it to be a departure from the sad reality, I like to imagine Tatum and Ryan O'Neal driving off to an uncertain but happy future together, devoted father and loving daughter, down that long and winding road into the horizon.

Isn't nostalgia all about remembering the past as we would have liked it to be?

|

| And They Lived Happily Ever After |

BONUS MATERIAL

On the DVD commentary, Bogdanovich reveals that it was his friend Orson Welles who came up with the idea to title the film "Paper Moon." Before the property fell into Bogdanovich's hands, the film was still known as "Addie Pray" (the title of the Joe David Brown novel) and conceived as a project for Paul Newman and his daughter Nell, working under the direction of John Huston.

YouTube clip of Tatum O'Neal winning her Oscar for Paper Moon - HERE

|

| In 1974, Paper Moon was turned into a short-lived TV series starring Jodie Foster (just two years away from her own Oscar nomination in Taxi Driver) and Christopher Connelly, the actor who played Ryan O'Neal's brother in 1964's popular TV soap opera Peyton Place (itself a spin-off of a motion picture). YouTube Clip of the series' opening sequence. |