Spoiler Alert. Many crucial plot points are revealed and referenced for the purpose of analysis. If you've never

seen The Conversation, don't spoil your fun. The mystery is too good. Watch the movie and then come back. I'll still be here.

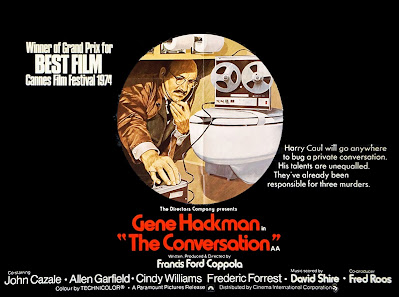

Although Francis Ford Coppola began writing his script for The Conversation sometime

in the late 1960s, and the film went into production well before all the details

of the Watergate scandal became known to the public (it was released mere

months before then-President Nixon’s resignation in August of 1974); few ‘70s films capture the wary

pessimism of post-Watergate America quite like The Conversation. A

small-budget, studio-interference-free, auteur project, Paramount granted Coppola a bid to secure his services for The Godfather Part II, a film he wasn’t interested in making. The Conversation is a detective movie crossed with a character study, reimagined as the quintessential 1970s

paranoid thriller.

|

| Gene Hackman as Harry Caul |

|

| John Cazale as Stan |

|

| Harrison Ford as Martin Stett |

|

| Teri Garr as Amy Fredericks |

|

| Cindy Williams as Ann |

|

| Frederic Forrest as Mark |

|

| Robert Duvall as The Director/Mr. C./Charles |

Harry Caul (Hackman) is a career wiretapper. A skilled audio

surveillance man who’s (ironically) very well-known in the spy-for-hire field of surreptitious

information-gathering. A loner and an outsider, Harry is ideally suited to his

craft not only because he’s a man of such unprepossessing countenance that he

doesn’t even seem to occupy the space he’s inhabiting, but because he lives his

life by the credo - "Don’t get involved." Amongst the many complex electronic gadgets and

devices in his professional arsenal, Harry’s own emotional detachment and studied

lack of curiosity are his most valued. Indeed, “Nothing personal” could be the byline on

his business cards. (That is, were Harry the type to use

business cards. For a guy like him, they divulge entirely too much personal

information.

Like defense lawyers who revel in the thrust-&-parry byplay of courtroom skirmishes, triumphant in their victories, yet heedless of the harm they do when their academic legal machinations result in the release of drunk drivers and hardened criminals back onto the streets; when it comes to the gathering private information, Harry sees himself simply as a techie problem-solver. He enjoys solving the strategic and electronic

puzzles posed by his job, but he never gives a thought as to why his clients want his services, how they intend to use the sensitive material he provides, or whether or not he is in any way culpable for any

misfortune that might befall others as a result of his actions.

"I am in no way responsible" and "It has nothing to do with me" are his professional mantras.

But unless one is a sociopath, indifference to human

suffering always comes at a price. And for Harry (a man haunted by the memory

of the part his work played in bringing about the brutal torture deaths of an

entire family) the price is that he has become a man who strives not to be seen

or known by others. Chiefly because he wishes he didn’t have to see or know

anything about himself.

Harry’s trademark professional detachment is put to the test

when a logistically complex, otherwise routine surveillance job (involving the

recording of a conversation between a man and a woman in San Francisco’s

crowded Union Square) unearths a probable murder plot. In listening and

re-listening to his recording of what on the surface sounds like a wholly innocuous

conversation between two clandestine young lovers (Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest), Harry comes

to believe, with mounting certainty, that he is once again in a situation where the plying of his trade will bring about the deaths of innocent people—in

this instance, a young couple who both speak as though they live in dire fear of a mysterious individual.

Compelled by equal parts empathy (the woman reminds him

of Amy, his neglected girlfriend), the dread of history repeating itself, and the chance for (self)absolution, Harry

breaks his cardinal rule of not allowing himself to feel anything about the

subjects of his surveillance work. Devoid of any clear plan of action, he resolves

to do what he can to prevent the occurrence of what he suspects and deeply dreads.

As Harry Caul delves deeper into an investigation of the

mystery, The Conversation chillingly reveals

that there’s more to matters of comprehension, interpretation, and perception than

meets the ear.

If post-Depression-era films are typified by their reinforcement of the principle that the individual and common man can still wield power and influence over systemic corruption (Mr.

Smith Goes To Washington, Meet John

Doe), then post-Watergate cinema

hammered home the impotence of the average man in the face of widespread moral

decay and venality. The Vietnam War and Watergate forced America to lose its

illusions about itself. Thus, '60s films like They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, then

later, the ‘70s films The Parallax View and Chinatown (both released the same year

as The Conversation) all supported the notion that no matter what one does, the decks are stacked, the die is

cast, and individual intervention is futile in the face of evil's ascendancy.

In sharing themes having to do with the unreliability of what is superficially seen and heard, Roman Polanski’s Chinatown

has a lot in common with The Conversation. Both lead characters (Jack Nicholson’s private eye/Gene Hackman’s

wiretap expert) are introduced as individuals afflicted with a kind of moral cynicism born of past events wherein their actions inadvertently brought about the deaths of others. They are also characters whose fortunes only take a turn for the worse after they've abandoned their cynicism, developed a

conscience, and sought redemption by way of a current correction of past errors.

|

| Allen Garfield as William P. "Call me Bernie" Moran |

The Conversation’s

Harry Caul is the living embodiment of Vietnam America: a willing, guilt-ridden

participant in morally dubious activity who rationalizes the sometimes deadly

ramifications of his actions by deluding himself that they have nothing whatsoever to do with him.

This spiritual deal with the devil clearly plagues the devoutly religious Harry

in his day-to-day life, resulting in his living a paranoid, loner’s existence of arms-distance friendships, inarticulate

romances, and a near-constant suspicion of the motives of others.

|

| Elizabeth MacRae as Meredith (Best known to folks of my generation as Lou-Ann Poovie, Jim Nabors' southern-fried girlfriend on Gomer Pyle: USMC) |

But Harry’s Achilles heel and tragic flaw—despite his best efforts—is that he really hasn't become as callous and indifferent to the world as he'd like to be. He's a man who struggles with his humanity (he regularly goes to confession) in a world that continually reconfirms that feelings...all feelings...are a liability and source of pain. Yet something within him still fights against complete callousness. Thus making Harry's uncharacteristic decision to involve himself in the saving of the lives of the two lovers a simultaneous, last-gasp attempt to save his own life as well.

What plagues Harry most about this otherwise humane decision to act...what stands as both the source and substance of his dread...is the fear that, should this assignment turn out like the other, with innocent lives lost, the result could lead to the irretrievable loss of what's left of his soul.

"This is no ordinary conversation. It makes me feel...something...."

A prevailing characteristic of the '70s paranoid thriller is how they provide no

reassurance that conspiracies aren’t real. Nor do they contradict the notion of paranoia as a rational, reasonable response to a reality of diminished privacy and corrupt authority figures.

Conceivably, as a means of conveying to the viewer that Harry Caul is a better man than his choice of profession would belie (he's more a gadget geek than a spy), The Conversation establishes from the get-go that Harry is singularly ineffectual when it comes to keeping his life private. He's not nearly the opaque, stealthy, character he imagines himself to be. In fact, it seems as though the conclusion of the film suggests that Harry has not been paranoid ENOUGH.

Conceivably, as a means of conveying to the viewer that Harry Caul is a better man than his choice of profession would belie (he's more a gadget geek than a spy), The Conversation establishes from the get-go that Harry is singularly ineffectual when it comes to keeping his life private. He's not nearly the opaque, stealthy, character he imagines himself to be. In fact, it seems as though the conclusion of the film suggests that Harry has not been paranoid ENOUGH.

For example, In spite of multiple locks on his door, an alarm system, and a refusal to divulge personal information to anyone, Harry's landlady not only finds out about his birthday and his age but manages to leave a gift for him inside his apartment when he is away. This scene, coming as it does after the opening sequence which details how anyone can be observed anywhere, is notable for the open blinds in Harry's apartment, revealing a moving construction crane ostensibly working outside of his window (an element made more obvious in the original script). A point that later plays into answering a third act disclosure revealing how Harry’s mysterious employer has always maintained an awareness of Harry's comings and goings.

|

| Harry grows uneasy when his girlfriend Amy lets on that she knows he spies on her and listens to her phone calls |

A recurring motif contributing to the bleakness of The Conversation's worldview is that Harry, for all the effort expended in insulating himself, is really the most exposed and vulnerable person in the film. Unable to connect with anyone (not even the couple he's trying to save), he is easily followed, bugged, tricked, spied upon; and, in those moments when he does try to open up, too easily betrayed. In the end, it's clear Harry is both a victim and an (unwitting?) victimizer at constant risk of dying by the very sword he lives by.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

The Conversation

is an intriguing thriller that builds its suspense honestly and ingeniously. A thriller made all the more compelling by the way it combines the familiar tropes of the suspense thriller with the intimate intensity of the character-study film. And while (unlike many suspense thrillers) the humans take precedence over the plot in The Conversation, what a doozy of a plot it is! (In 1975, Gene Hackman would play another self-confronting private investigator in Arthur Penn's Night Moves, a nihilist '70s spin on the 1940s film noir.)

The Conversation is at its most successful when drawing the viewer into questioning the significance of superficially banal dialogue and mundane-appearing activities. The Conversation mines the suspense in its ordinary characters and the gritty squalor of their lives in a way reminiscent of what Alan J. Pakula achieved in Klute (1971). And for evoking paranoia and isolation, the purposeful use of San Francisco locations in The Conversation recalls Philip Kaufman’s brilliant 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

The Conversation is at its most successful when drawing the viewer into questioning the significance of superficially banal dialogue and mundane-appearing activities. The Conversation mines the suspense in its ordinary characters and the gritty squalor of their lives in a way reminiscent of what Alan J. Pakula achieved in Klute (1971). And for evoking paranoia and isolation, the purposeful use of San Francisco locations in The Conversation recalls Philip Kaufman’s brilliant 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

|

| There's a big retro kick to be had in the proliferation of pay phones and primitive sound equipment on display. |

PERFORMANCES

The Conversation

was not a success when released in April of 1974, and with that year's December release

of Coppola’s The Godfather, Part II,

it was all but forgotten by audiences and critics alike. It did garner three Academy Award nominations (Best

Picture, Original Screenplay, & Sound), but in a tough acting year crowded

by the likes of Jack Nicholson (Chinatown),

Dustin Hoffman (Lenny), Al Pacino (The Godfather, Part II), and Albert

Finney (Murder on the Orient Express), Gene Hackman's commanding and sensitive performance was

crowded out. (I love Art Carney, but his Harry

& Tonto nomination and win to me is positively baffling considering the heavyweight competition).

|

| All the supporting performances in The Conversation are outstanding, but Elizabeth MacRae, as the sad-eyed trade show model, is surprisingly good and deeply affecting |

In Harry

Caul, Gene Hackman (2nd choice after Marlon Brando turned down the role) gives what I consider to be the best performance of his varied and very

impressive career. Portraying a closed-off character is always a challenge;

playing one who must convey to the audience the gradual reawakening of

conscience is something else again. The entirety of whatever dramatic

effectiveness or potential for audience involvement in The Conversation has rested on the credibility of Hackman’s

transformation. (And, tellingly, the film doesn’t require that you actually like Harry). On

that score, Hackman—with the inestimable contribution of the film's uniformly exceptional cast—is nothing short of extraordinary.

|

| The likely apocryphal story goes that Hackman gained weight and partially shaved his head for the role. The latter proved so problematic in growing back that it contributed to his refusal to shave his head for the role of Lex Luthor in Superman: The Movie (1978) |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

If you’re familiar with The

Conversation at all, you’ve likely read or heard about the perhaps equally apocryphal story about a fortuitous

transcription error that resulted in the original last name of Gene Hackman’s

character being changed from Call (perhaps a little too on-the-nose for a serious

film about a wiretapper) to the homophonous and oh-so evocative Caul. Caul is the name for the transparent protective membrane surrounding a fetus. Not one to spit in the

eye of serendipity, Coppola builds upon this happy spelling error and uses

it as both an allusive reference to Harry’s overly self-protective personality and a springboard for a series of recurring visual motifs dramatizing the human instinct to emotionally insulate.

|

| Rain or shine, the emotionally embryonic Harry is rarely seen without his "protective" transparent plastic raincoat |

The motif of protective yet transparent membranes simultaneously protecting and isolating individuals is further conveyed in The Conversation's use of obfuscating veils of semi-transparent surfaces. The whole blurred vision effect is suggestive of Harry not really having a clear perspective of what he's getting himself involved in.

Not Getting a Clear Picture of Things

|

| Hackman is filmed through a plastic sheet in this scene depicting Harry having a cagey conversation with an untrustworthy colleague (Garfield). |

|

| The crucial details of a harrowing event are obscured behind a gauze curtain |

|

| A glass partition prevents intervention while revealing only enough to horrify |

|

| A figure lies shrouded in a membrane of clear plastic |

Coppola and cinematographer Bill Butler (Demon Seed) frequently rely on wide-angle shots to cut the frame into sections, dramatically emphasizing The Conversation's themes of isolation, loneliness, and the inability to communicate or emotionally connect.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Beyond its obvious Watergate-era appeal and glimpse into a

cultural zeitgeist I still remember vividly, I have to say that what most makes

The Conversation a film I can rewatch

endlessly (per my tendency to gravitate to films from which I can glean

insights into the human condition) is that it is a powerful and persuasive allegory

about the risks of allowing oneself to be vulnerable.

|

| Watched |

Characters in The Conversation are fond of repeating phrases like “You’re not supposed to feel anything” and “Nothing personal,” but as (I hope) we all know, life is very personal, and any attempt to connect authentically with another human being is fraught with risk. It hurts; it’s

messy; it invades your space and disrupts order; it leaves you exposed to

betrayal, misunderstanding, and rejection. And worst of all, it comes with no

guarantees. On the contrary, it comes with the unequivocal assurance that the

closer you get to someone…the better they know you…the more open and exposed

you allow yourself to be...the greater the potential for them to do you harm.

|

| Watching |

But what of the alternative? Is it possible to exist among others with life’s

only objective being the hope that your path never intersects with another's? That “nothing personal” transpires to invade your heart and cause you pain?

As Harry Caul learns, not only does one embark on a course of self-isolation at the risk of losing one's soul and

humanity, but the biggest irony of all is how life has a way of happening to you no matter how diligently you try to keep it at bay. As the saying goes, no one here gets out alive.

|

| Watcher |

The Conversation

is a peerless ‘70s paranoia thriller, one certainly not lacking in present-day parallels. But the film's paranoia/conspiracy theme is but one of the many layers making up this intelligent, superbly-crafted film. Like the

audio tapes that plague Harry throughout the movie, The Conversation imparts more information and more insights the more you watch it.

BONUS MATERIAL

The stationery letterhead for Coppola's American Zoetrope San Francisco offices when they were housed in the Columbus Tower on Kearny Street. Someone familiar with Coppola's history can confirm, but I remember reading somewhere that the raised, circular letterhead graphic (depicting a dog with a camera in the center of a plate) is from a child's dish set from Coppola's youth or that of his father.

|

| Elizabeth MacRae in a 1967 episode from the 3rd season of the TV series Gomer Pyle: USMC highlighting the character of aspiring vocalist Lou-Ann Poovie |

When people wonder what was in the water during the 1970s, TV shows like that inspire the question.

Teri Garr and Gene Hackman in a clip from "The Conversation" (1974)

The Conversation on DVD & Blu-Ray

I haven't heard the commentary Francis Ford Coppola supplies for the most recent DVD release of The Conversation, but from what I've read, it offers a wealth of info about the making of the film (e.g., Harrison Ford got a bead on his character when Coppola informed him that Martin Stett was gay). Of particular interest for me are the things that were cut from the final film: 1) Harry is revealed to be the secret owner of the apartment building he occupies, 2) He is plagued by overly-friendly neighbors, 3) There was a subplot involving a niece [Mackenzie Phillips], and 4) The betrayal Harry suffers at the hands of a character turns out to not be as conspiratorially sinister as it appears to be in the finished film.

.JPG)