After seeing so many billboards, bus shelters, and mega-posters around

town heralding the forthcoming release of the latest (2014) screen incarnation of Annie – that pint-sized, ginger juggernaut

of Broadway 1977 (and for those keeping score, this marks adaptation # 3)—I

figure I'd better get around to covering John Huston's 1982 mega-budget, mega-hyped,

mega-merchandised movie version before public reaction to the remake—pro or con—influence my memories.

Since remakes, as a rule, tend more to be the brainchild of accountants than artists, I usually think of them as irksome, Hollywood-as-industry inevitabilities easy to dismiss on principle alone. When looking back on the recent remakes of classic and iconic films (for example, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory and Brian De Palma's Carrie), I can only see them as obvious fool's errands; useful only as reminders of what was so brilliant about the originals.

But when it comes to remaking flawed or flop films, I confess to being rather open to the idea. I mean, it does afford the opportunity for a new filmmaker to correct what might have gone awry with a property in its first outing, a chance to "get it right" the second time around.

The 1982 movie version of Annie is regarded as a beloved children's classic to many today, but it took quite a few years for it to grow on people. Upon its release, Annie was greeted with a mixed reaction by the press (it was nominated for 5 Razzie Awards, winning one for Aileen Quinn as Worst Supporting Actress); the considerably less-than-anticipated interest from the public; and was trashed in the press by the show's lyricist, Martin Charnin ("Terrible, terrible, it distorted everything!"). And although it emerged as one of the top ten moneymakers of the year, its steep budget ($40 to $50 million), hefty marketing campaign ($10 million), and record $9.5 million spent on acquiring the rights, meant it would be years before it came anywhere near to showing a profit.

The 1982 movie version of Annie is regarded as a beloved children's classic to many today, but it took quite a few years for it to grow on people. Upon its release, Annie was greeted with a mixed reaction by the press (it was nominated for 5 Razzie Awards, winning one for Aileen Quinn as Worst Supporting Actress); the considerably less-than-anticipated interest from the public; and was trashed in the press by the show's lyricist, Martin Charnin ("Terrible, terrible, it distorted everything!"). And although it emerged as one of the top ten moneymakers of the year, its steep budget ($40 to $50 million), hefty marketing campaign ($10 million), and record $9.5 million spent on acquiring the rights, meant it would be years before it came anywhere near to showing a profit.

While I wouldn't go so far as to call Annie a classic, neither would I label it the out-and-out failure its detractors make it out to be. Sure, at times the script is uneven to the point of feeling erratic (Hannigan's 11th-hour character redemption happens so abruptly it'll give you whiplash), but I still find many of its narrative changes to be a marked improvement over the theatrical production. And, thanks to its bouncy score, boundless—if unharnessed—energy, and capable, hardworking cast; Annie manages to be very entertaining despite never really gelling into the kind of touchstone movie musical event its Broadway success (and producer Ray Stark's investment) augured.

|

| Aileen Quinn as Annie |

|

| Albert Finney as Oliver Warbucks |

|

| Carol Burnett as Miss Agatha Hannigan |

|

| Ann Reinking as Grace Farrell |

As every living human must by now know, Annie is the significantly retooled movie version of the Tony Award-winning

musical phenomenon based on Harold Gray's "Little Orphan Annie" comic strip. Set in the Depression-era New York of 1933, Annie

is the story of a spunky, unflaggingly optimistic little orphan who, while dreaming

of finding her wayward parents, manages to rescue and adopt a bullied stray mutt; win the heart of a billionaire industrialist (or war profiteer, if you will);

play cupid for his devoted secretary; thwart a Bilko scheme cooked up by the villainous orphanage

matron, Miss Hannigan and her partners in crime, Rooster and Lily; and by fade-out, appears poised, with the help of FDR, to take on the Great Depression itself.

|

| Bernadette Peters as Lily St. Regis, Tim Curry as Rooster Hannigan |

As the estrogen-laced answer to 1962s boy-centric Oliver

(what DID little girls do in dance recitals before this show?) Annie is notable—before "Tomorrow"

took on a life of its own and became one of the most overexposed (and, in turn, annoying) songs ever written—for representing something of a 1970s pop cultural turning point. In a social

climate reeling from inflation, the oil crisis, post-Watergate disillusionment, Vietnam fallout, and the hedonism-as-religion retreat into sex & drugs which typified the Disco era (Annie opened on Broadway in 1977 mere months before the release of the bleak Looking for Mr. Goodbar): Annie was among the first non-ironic, unapologetically hopeful entertainments to emerge from a decade noted for its cynicism. Annie's assertively retro "corny is cool" philosophy rode a nostalgia zeitgeist that embraced the intentional camp of TV's Wonder Woman, Star Wars' updating of the 1930s sci-fi serial, and was part of the comic book mania that spawned 1978's Superman and Robert Altman's musicalized take on Popeye (1980).

Now, this is where things started getting weird. Broadway veteran Joe Layton (Thoroughly Modern Millie) was on hand to create the musical numbers (which makes sense), but the choreographic chores for this 1930s period musical—an innocent, if not naive, family entertainment swarming with children—fell to Arlene Phillips (which makes no sense at all). Certainly not if you're even remotely familiar with Phillips' very contemporary, hypersexual choreography for the Eurosleaze dance troupe Hot Gossip, or if you've ever seen her patented brand of disco/aerobic writhing in the films The Fan and Can't Stop the Music. I'm a huge Arlene Phillips fan, but even I had to scratch my head on this one. However, nothing raised eyebrows higher than the news that Annie, now known as Ray Stark's baby ("This is the film I want on my tombstone"), was to be directed by Oscar-winner John Huston, a Hollywood veteran of forty years, making his first musical at age 75.

Theories abounded as to the soundness of such a decision (Mike Nichols, Herb Ross, and Grease's Randal Kleiser had all been attached to the project at various times), but insiders likened Stark's handing over a lavish musical to a veteran director best known for gritty dramas (Reflections in a Golden Eye, The Treasure of Sierra Madre, The Misfits) to hoping history might repeat itself. Back in the '60s' three of the decade's biggest musical hits were the work of two veteran directors who'd never made a musical before: Robert Wise with the phenomenally successful West Side Story (1961) and The Sound of Music (1965), and William Wyler hit paydirt with Funny Girl (1968).

After months of the kind of strenuous prerelease hype that turns critics against a film before it even opens, Annie premiered here in Los Angeles at Mann's Chinese Theater in May of 1982. I was in line opening night (fewer kids at evening shows) having by now fairly whipped myself into a veritable frenzy of enthusiastic anticipation. With that cast, director, choreographer, and score, I was certain that Annie would be every bit "The Movie of Tomorrow" its ads promised.

Maybe…

Primed for Annie to be more of an event than a movie (it was one of the first films to charge a then-record $6 admission price), my first viewing was so ruled by my desire (need?) to like it, that I couldn't attest to really having seen the actual film at all. As I recall it, my first look at Annie was an exhausting evening of willful self-deception and near-constant internal cheerleading. I laughed too loud and hard at bits of business that barely warranted a grin, and I gasped in delight at predictable plot developments that must have seemed ancient back in the day of Baby Peggy. My only reactions that weren't artificial and inappropriately oversized were to the showy musical numbers, which were, indeed, pretty spiffy. Still, I'd literally worked up a sweat trying to stave off disappointment...all in an effort to convince myself that I was having a better time than I had.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS MOVIE

I've no real quarrel with the performances of Annie's grown-up cast. Finney is amusingly broad and cartoonish as Warbucks, Reinking is at her most eloquent when she lets her lithe body do the acting, and, the always-fabulous Carol Burnett is left to do all the comedy heavy-lifting as the perpetually pickled Miss —a role she's ideally suited for. Perhaps too much so. Burnett is a lot of over-the-top fun and never less than fascinating and spot-on. But watching her, I can't help thinking, as I often do when watching Maggie Smith on Downton Abbey, that she could do this kind of role in her sleep.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Mimicking the fate of many beloved children's movies that were not exactly hits when first released (The Wizard of Oz and the aforementioned Willy Wonka being the most famous examples), Annie may have had to take her lumps back in 1982, but, true to her optimistic credo, she's weathered a great many more "Tomorrows" than her more critically-revered peers.

Meanwhile, my own feelings about Annie have remained roughly the same, with time adding (in equal measure) a degree of nostalgia and cheesy camp to my revisits to it, making for a win-win situation whatever mood I'm in. So, whether it's to laugh at the baffling amateurism of some scenes (what must the outtakes of the orphan's rendition of "You're Never Fully Dressed Without a Smile" look like if this one, with its poor lip-synching and self-conscious "fun" was chosen?); ponder the possibility that perhaps all those up-the-skirt shots and peeks at women's underwear are part of a visual motif, or merely marvel at how impossibly young everybody looks... Annie may no longer be the movie of Tomorrow, but it offers a pretty pleasant look at yesterday.

I wish the 2014 remake of Annie all the best. We have yet to have our quintessential big-screen Annie.

BONUS MATERIAL

Want to watch a grown woman (Arlene Phillip) yelling at a bunch of overworked kids? Want to catch a glimpse of the deleted "Easy Street" number? Check out Lights! Camera! Annie! a 1982 PBS "Making of" documentary on YouTube.

Not sure where it's available to stream, but Life After Tomorrow is a fascinating 2006 documentary about the lives of former Annie orphans.

Disco touched everything in the late '70s, and sunshiny anthems by mop-topped orphans were no exception. In 1977 disco diva Grace Jones performed what can best be described as a confrontational version of "Tomorrow" HERE.

Speaking of disco, did you know Aileen Quinn released a solo album? Me neither. Her album, Bobby's Girl, was released in 1982 to take full advantage of the Annie media blitz. Although disco was fairly dead by this time, that didn't stop Quinn from driving at least one child-sized nail into its coffin by performing an ill-advised cover of Leo Sayers' 1976 boogie anthem, "You Make Me Feel Like Dancing." "Arf!" goes Sandy.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2014

While Annie's overwhelming

success guaranteed it a movie sale (at the time, commanding the highest price ever paid for a

theatrical property), media over-saturation in the intervening years of its theatrical run also made it a prime target of parody. When producer Ray Stark (Funny Girl) announced his plans to mount a big screen version, industry naysayers wondered how 1982 audiences would respond to what many now perceived as the show's machine-driven sentimentality and diminished novelty factor. Questions arose as to the issue of overexposure (Annie was still running on Broadway, and would until 1983) and wondering if the public was up to weathering yet

another shrill rendition of "Tomorrow" sung by a red-tressed, brass-lunged moppet.

As a West Coaster with access to only those Broadway shows successful enough to have touring companies, I'm one of those guys who'd rather have a

poor movie adaptation of a Broadway musical than none at all (see: A Little Night Music. However, Richard Attenborough's A Chorus Line is the exception that proves the rule). So I was on board

for a movie version of Annie from the get-go. But what

really made it a must-see film for me was the unusually high caliber of talent Stark had secured both in front of and behind the camera.

What he assembled was a dream cast for

Annie; actors who not only visually

fit their roles to a T, but bravely bucked recent Hollywood musical tradition by actually being able to sing and dance. Albert Finney, while acquitting

himself very nicely in the 1970 musical, Scrooge,

would be the first to admit he's neither a singer nor dancer, but Carol Burnett, Ann

Reinking, Bernadette Peters, Tim Curry, Geoffrey Holder (Punjab), and Roger

Minami (the Asp) were all seasoned performers who got their start in Broadway musical theater.

By 1982, Andrea McArdle, Broadway's original Annie, was roughly the appropriate age to play Lily St. Regis, so a massive, year-long, publicity-baiting

global search was launched to find the perfect little orphan for the film version. Cute 9-year-old Aileen Quinn beat out 9,000 crestfallen (if not scarred for life) Annie applicants, winning the title role in what was then the most expensive musical ever made.

|

| She & Sandy Make a Pair, They Never Seem to Have a Care. Cute Little She... it's Little Orphan Annie Aileen Quinn was paid the exact same salary as Bingo (one of three dogs portraying Sandy) |

Now, this is where things started getting weird. Broadway veteran Joe Layton (Thoroughly Modern Millie) was on hand to create the musical numbers (which makes sense), but the choreographic chores for this 1930s period musical—an innocent, if not naive, family entertainment swarming with children—fell to Arlene Phillips (which makes no sense at all). Certainly not if you're even remotely familiar with Phillips' very contemporary, hypersexual choreography for the Eurosleaze dance troupe Hot Gossip, or if you've ever seen her patented brand of disco/aerobic writhing in the films The Fan and Can't Stop the Music. I'm a huge Arlene Phillips fan, but even I had to scratch my head on this one. However, nothing raised eyebrows higher than the news that Annie, now known as Ray Stark's baby ("This is the film I want on my tombstone"), was to be directed by Oscar-winner John Huston, a Hollywood veteran of forty years, making his first musical at age 75.

Theories abounded as to the soundness of such a decision (Mike Nichols, Herb Ross, and Grease's Randal Kleiser had all been attached to the project at various times), but insiders likened Stark's handing over a lavish musical to a veteran director best known for gritty dramas (Reflections in a Golden Eye, The Treasure of Sierra Madre, The Misfits) to hoping history might repeat itself. Back in the '60s' three of the decade's biggest musical hits were the work of two veteran directors who'd never made a musical before: Robert Wise with the phenomenally successful West Side Story (1961) and The Sound of Music (1965), and William Wyler hit paydirt with Funny Girl (1968).

|

| Radio personality Bert Healy (Hollywood Squares host, Peter Marshall) is joined by the lovely Boylen Sisters in a rendition of "You're Never Fully Dressed Without a Smile" |

After months of the kind of strenuous prerelease hype that turns critics against a film before it even opens, Annie premiered here in Los Angeles at Mann's Chinese Theater in May of 1982. I was in line opening night (fewer kids at evening shows) having by now fairly whipped myself into a veritable frenzy of enthusiastic anticipation. With that cast, director, choreographer, and score, I was certain that Annie would be every bit "The Movie of Tomorrow" its ads promised.

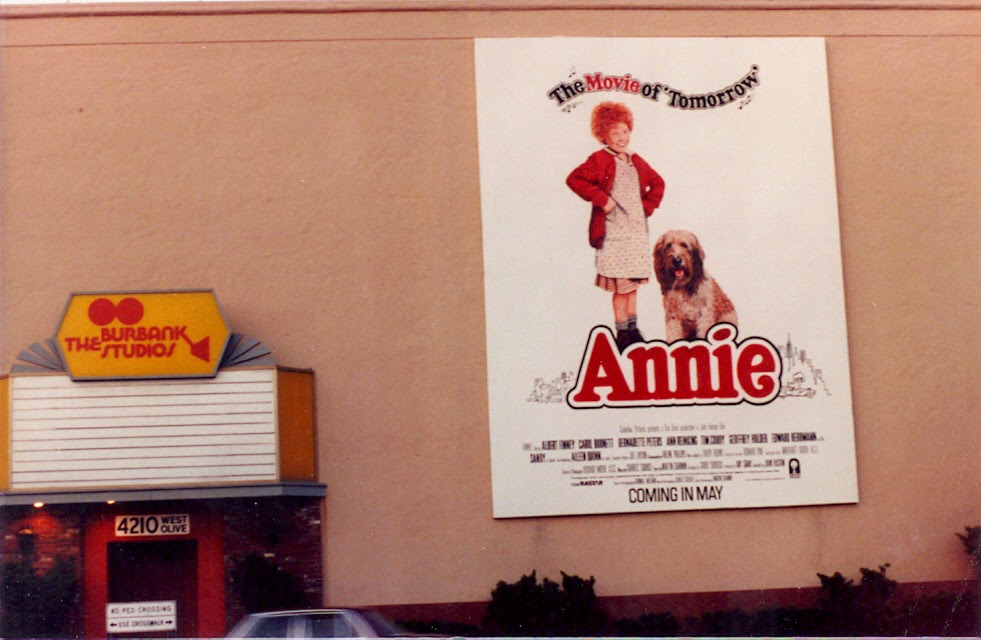

|

| A photo I took of the Burbank backlot that Warner Bros. and Columbia Studios have shared since the mid-'70s. Behind this wall stood Annie's $1 million New York outdoor street set |

Maybe…

I love that I get excited by movies (seriously, I gave myself a

nosebleed at the SF premiere of Thank God It's Friday), but I had double

reason to be worked up over Annie. First, as one of the biggest movie musicals

to be released since my Xanadu epiphany (read here), Annie

represented the first musical I'd be seeing since I started studying dance and took it up as a profession. In fact, I took classes with a couple of the dancers in the film who had been hired for

reshoots of the Radio City Musical Hall sequence and the since-jettisoned, grand-scale "Easy

Street" number, and they both assured me that Annie was going to be a bigger hit than Grease.

|

| Annie's Orphan Pals Captured in one of the rare moments one of them isn't staring directly into the lens or glancing distractedly at something off-camera. |

Primed for Annie to be more of an event than a movie (it was one of the first films to charge a then-record $6 admission price), my first viewing was so ruled by my desire (need?) to like it, that I couldn't attest to really having seen the actual film at all. As I recall it, my first look at Annie was an exhausting evening of willful self-deception and near-constant internal cheerleading. I laughed too loud and hard at bits of business that barely warranted a grin, and I gasped in delight at predictable plot developments that must have seemed ancient back in the day of Baby Peggy. My only reactions that weren't artificial and inappropriately oversized were to the showy musical numbers, which were, indeed, pretty spiffy. Still, I'd literally worked up a sweat trying to stave off disappointment...all in an effort to convince myself that I was having a better time than I had.

And the weird thing is, I really did have a good

time. I just didn't have a great time, which is what I expected of a $40 million film that took two years to make. This leads me to ponder the double-edged sword of hype: when it comes to movie marketing, there's

sell, and there's oversell...the former being when you give the public

information, the latter is when you give them ammunition.

Seeing Annie a second time convinced me that the film's problem wasn't that it failed to live up to expectations but failed to live up to its own potential.

Seeing Annie a second time convinced me that the film's problem wasn't that it failed to live up to expectations but failed to live up to its own potential.

|

| Make a Wish A victim of its own success, Annie was torn between the simple charm of its storyline and the Hollywood dictate that it be a larger-than-life musical extravaganza |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS MOVIE

As I'm fond of saying, a movie doesn't have to

be perfect in order for it to be either enjoyable or someone's all-time favorite. Annie's a glowing example of this principle in that it's a movie I never recommend to people, yet one I often revisit when I need my occasional overproduced movie musical fix. Straight dramas and comedies require cohesion in order to work. Not so with musicals. Musicals (happily) are by-design, broken into singing and non-singing interludes which, if need be, can be appreciated table d'hôte or à la carte. Annie is arguably at its best when experienced as separate scenes and isolated dance numbers. This way, the effectiveness of certain scenes (such as when the confounded Warbucks watches Grace put Annie tenderly to bed) isn't handicapped by clumsy adjoining sequences, and the musical numbers that click ("We Got Annie") get to stand alone and apart from those that fizzle ("Easy Street," to my shock and amazement).

PERFORMANCES

PERFORMANCES

One of the more fascinating things about those old Our Gang comedies of the '30s is how natural

all those kids were. No matter how often they were called upon to mimic grown-up

behavior, the charm was in their essential, unaffected childishness shining

through.

In Annie, the

little girls cast as orphans are all experienced troupers culled from Annie productions all over the country,

and it shows. While the film is desperately in need of an Annie with the kind of screen magnetism of a young Patty Duke, Hayley Mills, or Jodie Foster—something to set her apart from the other orphans and justify an audience's concern for her welfare—Aileen Quinn is a perfectly swell Annie (to use the vernacular). While not blessed with that intangible "something" that made Shirley Temple a charismatic and charming screen presence, Quinn has an earnest, winning quality, a pleasant voice, and best of all for an old grouch like me, fails to grate on my nerves.

This is in stark contrast to the rest of the orphans who are literally children working like Trojans to act like children…and they don't succeed! Annie was my first exposure to this kind of Disney Channel, plastic child-actor aesthetic that seems to have become the norm these days: old-before-their-years showbiz kids who can only impersonate (badly) the behavior of real children.

This is in stark contrast to the rest of the orphans who are literally children working like Trojans to act like children…and they don't succeed! Annie was my first exposure to this kind of Disney Channel, plastic child-actor aesthetic that seems to have become the norm these days: old-before-their-years showbiz kids who can only impersonate (badly) the behavior of real children.

I've no real quarrel with the performances of Annie's grown-up cast. Finney is amusingly broad and cartoonish as Warbucks, Reinking is at her most eloquent when she lets her lithe body do the acting, and, the always-fabulous Carol Burnett is left to do all the comedy heavy-lifting as the perpetually pickled Miss —a role she's ideally suited for. Perhaps too much so. Burnett is a lot of over-the-top fun and never less than fascinating and spot-on. But watching her, I can't help thinking, as I often do when watching Maggie Smith on Downton Abbey, that she could do this kind of role in her sleep.

|

| Carol Burnett made her Broadway musical debut in Once Upon a Mattress in 1959. Annie marks her very first movie musical appearance |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Annie's musical numbers always put a smile on my face. Sometimes, because they're so

good, sometimes because the lip-syncing is so poor or the execution is so unpolished, I have a hard time believing they made it into the completed film. Six songs

from the Broadway show failed to make it into the film, and I honestly can't say

I miss them. And of the four songs written expressly for the film, the only two

I could have done without are "Dumb Dog/Sandy" (in which the lyricist commits the Sondheim-wouldn't-do-this crime of putting the sophisticated word "residing" into the mouth of a little girl we'd previously heard say "piana" for piano). Also, I'm not particularly fond of the whole Rockettes section of "Let's

Go to the Movies."

|

| We Got Annie In one of my favorite numbers, Roger Minami, Ann Reinking, and the late great Geoffrey Holder dance together all too briefly, but it's pure magic. |

|

| It's The Hard Knock Life Can we please pause a second and appreciate Annie's amazing horizontal split jump? |

|

| I Don't Need Anything But You Annie gets it right in the charming finale, which gives Quinn the closest thing to a Shirley Temple moment |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Mimicking the fate of many beloved children's movies that were not exactly hits when first released (The Wizard of Oz and the aforementioned Willy Wonka being the most famous examples), Annie may have had to take her lumps back in 1982, but, true to her optimistic credo, she's weathered a great many more "Tomorrows" than her more critically-revered peers.

Meanwhile, my own feelings about Annie have remained roughly the same, with time adding (in equal measure) a degree of nostalgia and cheesy camp to my revisits to it, making for a win-win situation whatever mood I'm in. So, whether it's to laugh at the baffling amateurism of some scenes (what must the outtakes of the orphan's rendition of "You're Never Fully Dressed Without a Smile" look like if this one, with its poor lip-synching and self-conscious "fun" was chosen?); ponder the possibility that perhaps all those up-the-skirt shots and peeks at women's underwear are part of a visual motif, or merely marvel at how impossibly young everybody looks... Annie may no longer be the movie of Tomorrow, but it offers a pretty pleasant look at yesterday.

I wish the 2014 remake of Annie all the best. We have yet to have our quintessential big-screen Annie.

"We Got Annie"

Want to watch a grown woman (Arlene Phillip) yelling at a bunch of overworked kids? Want to catch a glimpse of the deleted "Easy Street" number? Check out Lights! Camera! Annie! a 1982 PBS "Making of" documentary on YouTube.

Not sure where it's available to stream, but Life After Tomorrow is a fascinating 2006 documentary about the lives of former Annie orphans.

Disco touched everything in the late '70s, and sunshiny anthems by mop-topped orphans were no exception. In 1977 disco diva Grace Jones performed what can best be described as a confrontational version of "Tomorrow" HERE.

Speaking of disco, did you know Aileen Quinn released a solo album? Me neither. Her album, Bobby's Girl, was released in 1982 to take full advantage of the Annie media blitz. Although disco was fairly dead by this time, that didn't stop Quinn from driving at least one child-sized nail into its coffin by performing an ill-advised cover of Leo Sayers' 1976 boogie anthem, "You Make Me Feel Like Dancing." "Arf!" goes Sandy.

"I love you, Daddy Warbucks."

|

| Trade ad heralding the start of production |

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)