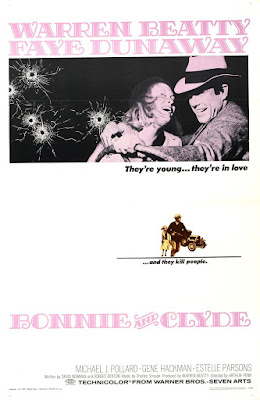

Bonnie & Clyde

is one of my “staple films.” A staple film being any movie that tops my

acquisition list whenever technological advancements make it necessary for me to

restock my film library. Back in the dark ages, when I got my first VCR machine,

Bonnie & Clyde, Rosemary’s Baby, and Midnight Cowboy were the first VHS

movies I ever purchased. These same films also became the first DVDs I ever

owned when video cassettes became obsolete. It wasn’t particularly planned that

way; they were just the three films I was most excited about owning in disc

format. As of yet, I haven’t jumped on the Blu-ray bandwagon, but if and when I ultimately

make that leap, it’s a sure bet which three films will be essential to have...again.

Arthur Penn’s Bonnie &

Clyde is a film that has arguably become as legendary and folkloric as its real-life

subjects. Released at the height of the hippie movement (ironically enough,

in August of the Summer of Love), Bonnie

& Clyde, in its myth-making depiction of two small-time Depression-era

outlaws, managed to hit America right between the eyes.

What captured our imaginations about Bonnie Parker and Clyde

Barrow in 1967 is most likely what also captured the nation’s imagination about the deadly duo in the

1930s. They were young (he was 21, she 19); women in crime were rare; as opposed

to being a “gang,” Bonnie and Clyde were perceived as a “couple” and as such, suitable

for romantic projection; and lastly, but perhaps most significantly, they were

famous. Indeed, they are among the earliest American “celebrity” criminals: self-aware

and image-conscious; knowledgeable of and taking delight in the notoriety and

fame their criminal activity brought them.

Had Arthur Penn’s film been less artful, say, a Roger Corman

exploitationer or an American-International cheapie like1958s The Bonnie Parker Story (an absolutely

must-see howler starring Dorothy

Provine), no one would likely have batted an eye on its release. But Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde comingled French New

Wave arthouse stylization with America’s romanticism of rebellion,

preoccupation with violence, and attraction to mythmaking, and in doing so, captured the absolute essence

of a particular moment in time. Not America in the 1930s, but America in the

late 1960s.

|

| Warren Beatty as Clyde Barrow |

|

| Faye Dunaway as Bonnie Parker |

|

| Michael J. Pollard as C.W. Moss |

|

| Gene Hackman as Buck Barrow |

|

| Estelle Parsons as Blanche Barrow |

(I literally had no business being in the theater at that

age, but precocious kids who make it their business to see movies too mature

for their age can’t really complain about the subsequent nightmares and

kindertrauma.) *I now own a framed Bonnie & Clyde poster which hangs where I can see it as I write. No longer a terrifying image, it inspires me and reminds me of the time when I thought movies were art and magic combined.

I had seen lots of crime dramas before this, but they were

all pretty cut-and-dried, morally speaking. Crime didn’t pay, the good guys

won, and the bad guys deserved what they got. I was not at all prepared for Bonnie & Clyde’s alternating tones

of comedy, romance, lyricism, drama, and in-your-face violence used in telling

the story of a duo many believed to have been little more than a couple of

hayseed sociopaths.

As embodied by the impossibly (implausibly?) beautiful and

stylish duo of Beatty and Dunaway, Bonnie and Clyde are a pair of

unsophisticated social misfits dreaming of a better life beyond the dustbowl poverty that surrounds them in Texas. Warren Beatty’s Clyde is a kind of

guileless career criminal with malice towards none (the film casts the Great

Depression as the ultimate villain) who sees in Bonnie a yearning soul, not

unlike his own. The film seems to imply that, possibly with education or

opportunity, this pair might have made something useful of their lives. But lacking

either and left with nothing but a nagging sense of the pent-up hopelessness of

their lives, they made the choice of antisocial rebellion.

A pretty nice name for a murderous crime spree.

And therein lay the cornerstone of the controversy surrounding

Bonnie & Clyde when it was first

released. Critics and audiences alike didn’t know what to make of a film that

not only intentionally altered (some might say manipulated) historical fact for

the purpose of dramatic effect, but cast its anti-heroes in a decidedly heroic,

romantic light that to some negated the very real pain and suffering this

real-life couple brought to others.

Director Arthur Penn has always maintained that he had

bigger fish to fry in Bonnie & Clyde

and had no interest in offering a documentary with a moral. In the excellent

but out-of-print volume, The Bonnie &

Clyde Book by Sandra Wake and

Nicola Hayden, Penn is quoted as saying: “I

don’t think the original Bonnie and Clyde are very important except insofar as

they motivated the writing of a script and our making of a movie. This is not a

case study of Bonnie and Clyde; we don’t go into them in any kind of depth.”

Instead, Penn asserts that he intended Bonnie & Clyde as a kind of post-Kennedy assassination/Vietnam War–era take on the death of the American Dream as manifest in the

nation’s fascination with violence and mythmaking, and the resultant anti-authority/anti-social rebellion.

Seeing criminals as simply good or evil is easier than understanding how poverty, lack of education, hopelessness, and powerlessness influence character development.

So if turning a couple of remorseless murderers into a pair

of sympathetic, glamorous, near-mythic tragic lovers was seen by some as

amoral, young '60s audiences didn’t seem to care. While critics like The New York Times’ Bosley Crowther

pilloried Bonnie & Clyde as “…a cheap piece of bald-faced slapstick

comedy that treats the hideous depredations of that sleazy, moronic pair as

though they were as full of fun and frolic as the jazz-age cut-ups in

Thoroughly Modern Millie,” young people across the country

responded (as they would two years later to Easy

Rider’s motorcycle-riding drug dealers) to the rebellious,

anti-establishment spirit at the film’s core.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT

THIS FILM

Putting aside arguments of amorality, I really admire

how Bonnie & Clyde captures

something I find to be very true about human nature: that the villains and

monsters of the world don’t necessarily perceive themselves to be such. Movies and pulp literature have taught us that bad guys are

well aware of how evil they are; literally reveling in their wickedness and

lack of conscience (to believe so is reassuring when you find yourself rooting for their

demise). Yet life experience and election-year observations have led me to

conclude that some of the most heinous people in our culture actually seem to maintain a perception of themselves as being basically good and “just folks.”

It makes perfect sense to me that neither Bonnie nor Clyde

would ever see themselves as bad guys. Dunaway and Beatty’s scenes together

depict the two as marginalized loners—zeroes in the eyes of the world—whose dead-end

lives converge, creating a kind of pitiful, doomed hope. They are a sadsack

Romeo & Juliet made stronger and more significant in their union than they

could ever be on their own.

Their world may be narrow and their thinking delusional,

but they long for the same things we all do. We identify with their taking

offense at the injustice of poor people being put out of their homes by banks,

and we may even applaud their standing up for the “little people” in the small

criminal ways they flout authority. Yet at the same time, we are repulsed by their

callous disregard for life. Or rather, a certain kind of life.

In their world,

the death of a lawman does not hold the same weight as the death of a loved one

or an average citizen. A trenchant twist on the way death is militarized by our “civilized society” (The death of an officer in battle does not hold the same weight as the death of a soldier; the death of a lawman in the line of duty does not hold the same weight as that of the average citizen, etc.) Small wonder that '60s youths - their lives valuable in terms of the draft, valueless when beaten by police during campus protests- found in Bonnie & Clyde a relevant parable for the times. Depicted as a pair of counterculture outlaws, at least Bonnie and Clyde were choosing to die on their own terms.

PERFORMANCES

In some ways, the channeling of a specific, defined persona

into role after role is the essence of what being a movie star (as opposed to

an actor) is all about. Diane Keaton trademarked the lovable, semi-inarticulate

ditz; Robert Redford the sensitive All-American jock; and Warren Beatty always

seemed to play some variation on the not-very-bright, overgrown boy with big

ideas (McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Only Game in Town, Shampoo). Notwithstanding

Beatty’s appealingly debauched beauty as a man, his screen persona has often

left me wanting. Not so in Bonnie &

Clyde. Here, he mines the mother lode of his star charisma and is

marvelously alive and interesting, especially in the scenes where Clyde explodes into

violent rages that erupt into a terrifyingly real physicality. Beatty playing aw-shucks

humble has always been a little boring. Beatty as a temperamental nutjob (Bugsy), is a sight to behold.

There’s a kind of wistfulness that comes over me whenever I

see Faye Dunaway in Bonnie & Clyde.

Part of it’s nostalgia because I fell in love with her in this movie; part of

it’s due to her being so damned good that I’m forced to admit that I’ve let it become

far too easy over the years to forget what a marvelous actress she is. You see her here, and

you know in an instant that there was no way this woman wasn’t going to be a

star. Her Bonnie Parker is funny, tough, and oh, so heartbreaking. Hers is a classic,

one-of-a-kind performance, and Dunaway OWNS the role as far as I’m concerned.

Any planned remakes would do well to distance themselves from the Penn film and

save all prospective Bonnies from the inevitable embarrassing comparisons to

Dunaway.

|

| Impotent Clyde seduces Bonnie with a phallic substitute |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

While the sympathetic light Bonnie and Clyde are presented

in represents an insurmountable hurdle for some (personally, I don’t see it as

sympathetic so much as human. A moral imperative overrides everything that

happens in the film), I find myself grateful for being allowed to take in the

events of the story without being forced by the script to adopt an attitude about

the pair until I’m ready.

One good example of this is the scene in which Clyde proudly boasts to a farmer whose house has been foreclosed, "We rob banks!” because, in that split second, we see an aimless man find his life's purpose. A few scenes later, Bonnie says these exact words to gas attendant C.W. Moss, and in her delivery, we

see that she at last has discovered an identity for herself, as well.

These two moments of empowerment for Bonnie and Clyde are perhaps

pathetic and delusional to us, the viewers, but they are defining moments for

the characters. What may come across as the film striking an amoral stance is

actually, I believe, the film merely establishing its point of view. The film

presumes we are adult enough to be shown Bonnie and Clyde reveling in their naive, self-serving view of the world and themselves (as misunderstood folk heroes like Robin & Maid Marian) without

insisting that we accept it.

Clip from "Bonnie and Clyde" (1967)

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Or rather, the stuff of nightmares. In this, I’m referring to

Bonnie & Clyde’s groundbreaking, much-discussed,

heavily-debated, then-unprecedented depiction of violence. Modern audiences may

find it tame (me, I still have a hard time watching the final ambush scene), but

everything you’ve read about it is true when it comes to how it affected

audiences on its initial release.

I still can remember how ear-shatteringly loud

the shots sounded in the theater, and how deadly quiet the theater was when the

film was over. People walked out of the film as if in a daze. Nobody

knew quite how to take what they had seen.

Part of it was that we all remembered how much we giggled at those scenes of hillbilly awkwardness and those Keystone Cops-like chase scenes with the lively banjo plucking in the background. We all felt like we'd been thrown a cruel curve...make us laugh at these people, then make us care about them, then kill them!

There were the obvious few, made so nervous

that they had to start saying ANYTHING quick, but I remember my family and me leaving

the theater and actually feeling afraid to say anything. As if in opening our

mouths, we weren’t sure what would come out…a cry or a scream.

|

| Bonnie & Clyde: Laughing and dying "The killing gets less impersonal and, consequently, less funny." Arthur Penn |

|

| Bonnie and Clyde opened in San Francisco theaters on November 1st, 1967 |

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2012