"You finally made it, Frankie. Oscar Night!.

And here you sit, on top of a glass mountain called 'success.' You're one of

the chosen five, and the whole town's holding its breath to see who won it.

It's been quite a climb, hasn't it, Frankie? Down at the bottom, scuffling for

dimes in those smokers, all the way to the top. Magic Hollywood! Ever think

about it? I do, friend Frankie, I do…."

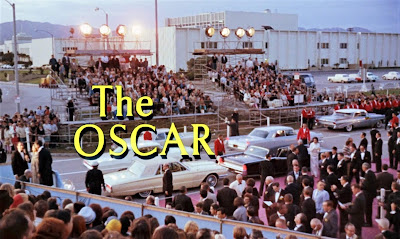

And thus begins one of the most sublimely terrible movies

ever to grace the screen. A speech rife with overelaborate hyperbole (it's hard to imagine anyone taking the Oscars this seriously, even in the '60s), clumsy metaphors, labored clichés,

and the name "Frankie" repeated no less than three times in a single breathless paragraph. Remarkably, three (count 'em, three) screenwriters are responsible for the dialogue in this gilt-edged burlesque, which, given how the characters are prone to repeat the name of the very person to whom they're speaking, sounds as though it were written for the radio.

|

| Frankie Goes to Hollywood Stephen Boyd with Johnny Grant, the real-life honorary Mayor of Hollywood |

With nary an ironic or self-aware bone in its bathetic, threadbare body, The Oscar is the

kind of pandering-yet-earnest, self-serious Hollywood trash no one has the old-school, out-of-touch naiveté to know how to make anymore.

A 1966 film that would have felt warmed-over in 1960 (the year Ocean's Eleven and Sinatra's Rat Pack

made this kind of clean-cut, pomaded, sharkskin-suited, ring-a-ding-ding brand

of cool into a veritable brand), The

Oscar is from the Joseph E. Levine (The Carpetbaggers,

Harlow) school of overlit, elephantine

artifice. Every interior looks like a soundstage, everyone's clothes look as

though they've never been worn before, and the characters are so lacquered and buffed they resemble department store mannequins.

|

| The Oscar opened in Los Angeles on Wednesday, February 16, 1966 at the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood |

As though encouraged to get into the spirit of things, The Oscars' flirting-with-obsolescence "all-star

cast" (eight Oscar winners in all) contribute performances that somehow manage to be mannequin stiff and over-the-top at the same time. Performances wholly unacquainted with human psychology, normal speech patterns, or recognizable human behavior.

With each viewing of this unrelentingly unconvincing take on what I assume was intended to be a cautionary tale about the dangers of unbridled ambition, I grow less and less surprised that one of its screenwriters (Harlan Ellison) is known principally for his work in science fiction. |

| Stephen Boyd as Frankie Fane "I'm fighting for my life! And there's a spiked boot for anyone who gets in my way." |

|

| Elke Sommer as Kay Bergdahl "It's that seed of rot inside of you that makes you what you are that you can't change. You just dress it better!" |

|

| Tony Bennett as Hymie Kelly "You lie down with pigs, you come up smelling like garbage!" |

|

| Eleanor Parker as Sophie Cantaro "You go after what you want. In some men, it's admirable. In you, it's...unclean!" |

|

| Milton Berle as Arthur "Kappy" Kapstetter "You never know you're on your way out until suddenly you realize it would take a ticket to get back in." |

The Oscar, subtitled: Memoirs of a Hollywood Louse, is an unabashed laundry list of every show biz/Hollywood cliché handed down since What Price Hollywood? (1932). A beyond-camp, glossy soap opera whose overripe performance and purple prose present the first male-centric challenge to the women of Valley of the Dolls (and Beyond).

Stephen Boyd, he of the narrow frame and chiseled, Tom of Finland profile, is Frankie Fane; your garden-variety ruthless user with a

suitable-for-movie-marquees alliterative name. Side note* I don't recommend anyone try playing a drinking game in which you take a shot every time someone in the film says Frankie's

name; you'll be rushed to the hospital with alcohol poisoning by the 20-minute mark.

As this told-in-flashback opus begins, Frankie and longtime

buddy Hymie Kelly (Tony Bennett, making his film debut/swansong and looking

like he wished he were back in San Francisco with his heart) are eking out a

living, largely thanks to the bump-and-grind efforts of Frankie's stripper

girlfriend, Laurel Scott (Jill St. John).

|

| Jill St. John as Laurel Scott "What does he think I am, dirt? Every morning I'd get the feeling he was gonna leave two dollars on the dresser for me!" |

After a nasty run-in with a crooked sheriff—a bulldoggish

Broderick Crawford playing the flip side of his Highway Patrol TV character—the vagabond trio thumb a

ride to NYC where breadwinner Laurel (who's, of course, basically a nice,

decent girl who just wants "a kid") soon tires of Frankie's freeloading.

This is in spite of the fact that Hymie, the perennial 3rd wheel and clearly healthy as an ox, also appears to be living with the couple, yet shows no signs of being any more gainfully

employed than his pal.

As audiences wait in vain for Hymie to happen upon a

microphone and solve everyone's problems by discovering a latent talent for singing (and, in the bargain, providing a much-needed respite from the film's ceaseless stream

of risible dialog and '60s slang); Frankie the hound dog decides to accompany

Hymie to "a swingin' party in the village…lots

of chicks" where he meets aspiring costume designer Kay Bergdahl (Sommer).

In no time, Frankie makes his move:

Frankie- "You a tourist or a

native?"

Kay- "Take one from column

A and two from column B and get an egg roll either way."

On the strength of that nonsensical rejoinder, one would be

forgiven for leaping to the assumption that Kay was suffering a

stroke-related episode and in need of immediate medical attention, but not our

Frankie. Clearly smitten by Kay's pouting accent, silk-awning bangs, and mink

eyelashes, our smarmy antihero instead continues to engage the comely blond in more Haiku-inspired

small talk. Kay, perhaps as a nod to the film's title, has a way of making everything she says sound like excerpts from an Academy Award acceptance speech:

|

| "I am the end result of everything I've ever learned...all I ever hope to be, and all the experiences I've ever had." |

Uhmm...O.K.

We return now to Laurel—that hip-switchin', nice-walkin', bundle of loveliness—who, in a late-in-coming display of backbone, lays down the law to Frankie when he returns home:

"If you think I'm gonna work my tail off so

you can run around with the village chicks…oh, stop spreadin' the pollen

around, Frankie...or else!"

Unfortunately for Laurel, her ultimatum doesn't have the desired effect on Frankie as she'd hoped. After spending the evening with hard-to-get Bergdahl, round-heeled Laurel starts to look like used goods to him, and in record time, Frankie, the village pollen-spreader, beats a hasty retreat. So hasty that he misses out on hearing the joyous news that Laurel is

pregnant with his child.

|

| Koo Koo Frankie shows a wise guy actor (Jan Merlin) what it's like to be on "the business end of a knife." |

Frankie expends so

much abusive energy exorcising his inner demons ("The way he sees it, no woman's any better than his mother," intones

Hymie, deep-thinker) that Kay scarcely has time to examine her own Bad Boy attraction issues ("Sometimes I get the feeling,

Frankie, that you ought to be chained up with a ring in your nose!") before their relationship begins to go south and take on all the dysfunctional sparring rhythms of

Robert De Niro & Liza Minnelli in NewYork, New York…minus the warmth & mutual respect.

One particularly

theatrical outburst of Frankie's captures the rapacious eye of roving

talent scout Sophie Cantaro (Parker), who sees in Frankie's mercurial mood

swings the makings of a star (Charlie Sheen, no doubt). Faster than you can say, "Bye-bye, Bergdahl! Hello, Cougar Town!" Frankie is whisked off to Hollywood

and becomes exactly the kind of noxious nightmare of a movie star you'd expect. Think Neely O'Hara crossed with Helen Lawson combined with every

ego-out-of-control rumor you've ever heard about Jerry Lewis, and you get the

idea.

|

| Joseph Cotten as Kenneth Regan, head of Galaxy Pictures "I find myself repelled and repulsed by you." |

Yes, whether it be the

simile-laden narration ("Man, he wanted

to swallow Hollywood like a cat with a canary."); the rote, claws-his-way-to-the-top

conflicts ("The fact is my 10% before

taxes is paying your office overhead. And you stop earning it when you stop giving

me what I want!"); or clumsy, tin-eared metaphors ("Have

you ever seen a moth smashed against a window? It leaves the dust of its wings.

You're like that Frankie, you leave a powder of dirt everywhere you touch."),

The Oscar leaves nary a cliché unturned and untouched.

And for that, we should all give thanks.

|

| Ernest Borgnine and Edie Adams as lowbrow couple Barney & Trina Yale |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT

THIS FILM

The Oscar is artificiality

as motif. Without actually intending to do so, director Russell Rouse (who made the must-see Wicked Woman -1953) has crafted a film so phony and plastic,

it winds up saying a great deal more about the real Hollywood than this contrived, self-serving fairy tale. A fairy tale that would have us believe that Hollywood

is comprised of basically decent, principled, hard-working folks, and that unscrupulous bad apples like Frankie are the rotten exception.

When I watch The Oscar, I always wonder: was this movie

pandering to star-struck yokels and hicks from the sticks? Was this fable of Tinseltown-as-Toilet designed to make Nathanael West's "locusts" feel less-resentful of the rich, famous, and privileged? To feed us the comforting fantasy that those beautiful, glamorous people on the screen have it far worse?

Or had years of lying to itself deluded "The Industry" into believing its own

publicity? This can't be how '60s Hollywood actually saw itself, can it?

It's not as though no one knew what a good film about Hollywood looked like: Sunset Boulevard -1950, The Bad & the Beautiful -1952, A Lonely Place -1950, Stand-In -1937. So, I tend to think everyone involved in The Oscar knew precisely what kind of trash they were

making (Bennett doesn't recall the experience fondly in his memoirs) and just cashed their paychecks and moved on. But given the

expense, effort, and the fact that many equally overstuffed, fake-looking, questionably-acted, and poorly-written films that came before it had somehow managed to find boxoffice success (The Carpetbaggers

comes to mind); I can only imagine that the eventual awfulness of The Oscar

wasn't as much of a surprise to those involved as was the public's total

indifference to it.

PERFORMANCES

It's a crowded, competitive field, but Stephen

Boyd walks away with the honors for The Oscar's most

exaggerated, indicating performance. In a film of parody-worthy performances, Boyd's bellowing, bombastic over-emoting (much like Faye Dunaway's in Mommie Dearest) sets the bar. It serves as the tonal rudder for this Titanic testament to overstatement. It's a performance that towers over the rest. And while one might argue he's no worse than anyone else (certainly not Bennett) and only as good as the knuckleheaded

screenplay allows; when there's this much collateral damage, every offender has to be held accountable for their fair share of the carnage.

|

| Frankie's cutthroat efforts to win an Oscar make up the bulk of the 1963 Richard Sale novel upon which the film is based, but comprise only the last half hour of the movie |

Indeed, in a reversal of my usual standard in camp movies I

adore, the women don't really dominate in The

Oscar. Despite their towering hairdos and colorful wardrobes, Elke Sommer, Eleanor Parker, Jill St. John, and a woefully

over-rehearsed Edie Adams have their work cut out for them in trying to keep

pace with the hambone scenery-chewing of Boyd on one side, and the Boo Boo Bear

blandness of mono-expression crooner Tony Bennett on the other.

|

| Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci They're Not Hope you like Tony Bennett's expression here, 'cause that's it...for two whole hours |

Add to this, schticky comedian Milton Berle as another one of

those saintly talent agents that only seem to exist in Joseph E. Levine films (Red Buttons,

another face-pulling comic, played a similar role in Levine's Harlow). Berle's approach

to serious drama is something out of an SCTV Bobby Bittman sketch: go so low-wattage as to barely

register any vitality at all.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

As hard as it is to believe that the Motion Picture Academy actually endorsed this sordid melodrama (although it is thought that the embarrassing flop of this film is responsible for the copyright stranglehold the Academy has had on the use and depiction of the Oscar Award in movies ever since), one must also wonder about the numerous drop-in guest appearances of so many "stars" adding verisimilitude and unintentional comic relief. Were they contractual, were favors owed, or were they simply prohibited from reading the entire script?

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

|

| Not sure, but I think knuckle-biting to convey distress went out with silent movies. |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

As hard as it is to believe that the Motion Picture Academy actually endorsed this sordid melodrama (although it is thought that the embarrassing flop of this film is responsible for the copyright stranglehold the Academy has had on the use and depiction of the Oscar Award in movies ever since), one must also wonder about the numerous drop-in guest appearances of so many "stars" adding verisimilitude and unintentional comic relief. Were they contractual, were favors owed, or were they simply prohibited from reading the entire script?

|

| Edith Head (or an animatronic copy) as Herself |

|

| Jack Soo as Sam, Frankie's live-in valet |

|

| Famed Hollywood columnist, commie-finger-pointer, and homophobic blabbermouth, Hedda Hopper |

|

| A puffy Peter Lawford is a little too convincing as Hollywood has-been Steve Marks |

Merle Oberon appears as an Oscar presenter and problematic pause-extender

|

| A beaming Frank Sinatra and daughter Nancy, in her brunette phase |

|

| Walter Brennan (right) as network sponsor Orrin C. Quentin of Quentiplak Products, Inc. On the left, one of my favorite character actors, John Holland, as Stevens, his associate |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

The bad film delights of The

Oscar are so myriad, I can only speculate that its relative unavailability is

to blame for its not having risen in camp stature equal to Valley of the Dolls or Mommie

Dearest over the years (it's not on DVD and pops up on TV only sporadically).

That, and its lack of an ostentatious drag queen aesthetic or even compelling

roles for women. I'm not sure why, but a lot of the best camp is rooted in

seeing women presented in the traditional, male-gaze "drag" of ornamental allure (big

hair, theatrical makeup, elaborate costumes) but behaving in non-traditional ways--i.e., assertive, aggressive, and with a plot-propelling agency (Faster Pussycat, Kill! Kill!).

The gender-norm incongruity of seeing ornamentally decked-out women behaving in the aggressive, toxic ways movies have traditionally ascribed to male anti-hero types, comes as a pleasant surprise

and welcome change of pace. It also probably accounts for why a nasty piece of work like Neely

O'Hara in Valley of the Dolls tends to remain in one's memory longer than the passive Jennifer North.

Despite giving lip service to the contrary, the women in The Oscar are a pretty passive bunch and more or less serve a traditional, reactive function

in the plot. Pointedly, the poised and elegant Sophie Cantaro, as one of the film's two exceptions (the other being the blowsy but street-smart Trina Yale), is

presented as both sexually desperate ("You, you're 42. There are many good minutes

left for you," a well-meaning, tactless friend tells her) and unable

to prevent her so-called "feminine" emotions from playing havoc with professional decision-making.

It's not difficult to imagine that The Oscar's preponderance of masochistic females is due to its three male screenwriters. This leads me to wonder if one of the reasons The Oscar never became the midnight screening hoot-fest its entertaining awfulness might otherwise augur is because the women's roles are so toothless.

But such wrong-headed thinking prevails throughout The Oscar. Making it one of the best of the worst, the apex of the nadir, and unequivocally one for the books. A book no doubt titled: "What The Hell Were They Thinking?"

Clip from "The Oscar" - 1966

Update: After being unavailable for decades, a Blu-ray edition of The Oscar was released on February 2, 2020.

|

| Elke Sommer wore the same Edith Head gown to the actual 1966 Academy Awards she donned in the fake ceremony that bookends The Oscar (top photo). Here's a clip of a somewhat botched dual acceptance speech with Connie Stevens for Doctor Zhivago's absent costume designer, Julie Harris. Watch HERE |