Spoiler Alert: If you haven’t yet seen the film and

wish to discover its surprises for yourself, stop reading now and come back later.

I’ll still be here.

One of the more effective,

least exploitative entries in the post-

Rosemary’s Baby occult sweepstakes (before

The Exorcist came along and switched up the game-plan, entirely), is 1971’s

The Mephisto Waltz. Adapted from the

1969 novel by Fred Mustard Stewart - which was itself a rather loud echoing of

Ira Levin’s 1967 novel -

The Mephisto Waltz

is a Satanic thriller that succeeds in being enjoyably stylish, suspenseful,

and marvelously kinky, while never actually giving Roman Polanski’s now-iconic film any

serious competition.

|

| Jacqueline Bisset as Paula Clarkson |

|

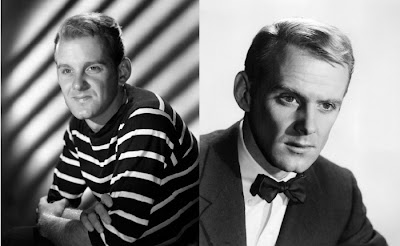

| Alan Alda as Myles Clarkson |

|

| Barbara Parkins as Roxanne Delancey |

|

| Curd Jurgens as Duncan Ely |

|

| Bradford Dillman as Bill Delancy |

Myles Clarkson (Alda), a failed musician turned struggling music journalist, lands an interview with world-famous classical

pianist, Duncan Ely (Jurgens). Taking note of Myles’ lyrical way with the

buttons on his tape recorder, the aging virtuoso (

“I happen to be the greatest

pianist alive!”) marvels at Myles’ perfect-for-the-piano fingers and declares him

to possess

“Rachmaninoff hands.” Hands that, according to Duncan (who should know,

I guess), only one in one hundred thousand possess.

And for the record, Duncan, when

not discovering new talent or wowing audiences with impassioned performances of Franz Liszt’s The Mephisto Waltz (“They don’t

understand that after a concert, there’s blood on the piano keys!”), finds time to be a practicing Satanist.

|

| While studying those concert pianist fingers, Miles fails to note how short his life-line suddenly got |

Having already learned from Rosemary’s Baby just how pushy devil-worshippers

can be, it comes as no surprise when Duncan and his witchily feline daughter,

Roxanne (Parkins), begin aggressively insinuating themselves into the lives of

Myles, his beautiful, no-nonsense wife Paula (Bisset), and their conveniently-disappearing daughter Abby (Pamelyn Ferdin). Faster than you can say “tannis root,” we find out that Duncan, who is dying of leukemia, has plans to serve Myles’ soul with an

eviction notice and take up residence in his lean yet alarmingly flabby body

ASAP…with a little help from the devil, of course.

Will the ever-suspicious

Paula, distrustful and jealous of the fawning attentions of Duncan and Roxanne

from the start, unearth the dark secret behind this creepily close-knit father/

daughter duo? Or will her pugnacious, Nancy Drew-curiosity and fortitude

(“…Well, I’m just one grade too tough!”) only serve to place her and her family

in greater danger?

The answers to this and many

more suitable-for-a-Black-Sabbath questions are answered in The Mephisto Waltz …a Quinn Martin

production. No, really, it is. The sole foray into feature film production by

the man who gave us The Fugitive, The F.B.I., Barnaby Jones, The Streets of

San Francisco, etc. However, to my great disappointment, The Mephisto Waltz is lacking in those

two great QM Production trademarks: the authoritarian narrator and the title

card breakdown of the story into separate acts and an epilogue.

This strikingly bizarre publicity photo of Parkins in the company of a dog wearing a human mask was used extensively in promoting The Mephisto Waltz in 1971

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

As I stated in a previous

post, I consider Rosemary’s Baby to be one of the

smartest, most effectively chilling films ever made; flawlessly effective both as a horror film and a psychological thriller. It’s

not only Roman Polanski’s cleverly black-humored approach to the material or the

finely-observed performances he elicits from his cast, but the source novel by Ira

Levin itself is a masterfully structured bit of Modern Gothic. A superior

example of contemporary horror.

When The Mephisto Waltz opened in theaters, the advance promotional buzz centered around its similarities to Rosemary’s

Baby. It promised to be just as scary, only sexier. I was all hopped up to see it, but, being

only 14 at the time, my mother (whose attentions were well-intentioned, if

inconsistent) wouldn’t let me see the R-rated feature. I had to satisfy my curiosity with a paperback copy of the novel from the local library. Upon reading it, I was

delighted to find the novel to be a genuinely suspenseful page-turner with a resourceful female protagonist trying to protect her home and family from sinister forces. Just the sort of thing Ira Levin specialized in.

|

FACE-OFF

Bisset and co-star bare their fangs |

Jump ahead to the 1980s and

adulthood, and I finally get to see The

Mephisto Waltz at a revival theater on a double-bill with its spirit cousin, Rosemary’s Baby. I wasn't disappointed. It’s no Rosemary’s Baby

by a long shot, but what it is is a nicely-crafted thriller that earns its chills honestly: through atmosphere, character, and suspense. If the

contrivances of plot seem somewhat rushed, and the performances and direction

only occasionally above your average '70s-era Movie of the Week TV standard; The Mephisto Waltz distinguishes itself

from the usual occult fare by force of sheer style. It's a great-looking movie enlivened by the air of kinky sexuality and amorality present in both its theme and main characters.

|

| The entire premise of The Mephisto Waltz asks that we accept that these two breathtaking beauties would be willing to fight, commit murder, and bargain their souls to the devil for... |

|

| ...this body. |

PERFORMANCES

When it comes to those flickering images of the gods and goddesses of the silver screen,

sometimes (perhaps too often, in fact) I find myself guilty of exactly the kind of

superficiality I thoroughly abhor in real-life: I cut the beautiful a great deal

of slack. Jacqueline Bisset is so stunning that I think I’m not as objective

about her acting ability as I might be. Frequently saddled with ornamental

roles during this stage of her career (she matured to a much more accomplished actress later), The Mephisto Waltz offers Bisset

a sizable lead role offering a considerable emotional range. So, how does she fare?

With her precise, clipped British diction and somewhat remote demeanor, Bisset handles the

scenes requiring her character to be sarcastic and confrontational pretty well. But she's a tad less

effective in scenes requiring she convey her character’s vulnerability and

fragile emotional state.

That being said, who cares! (OK, call me superficial) Jacqueline

Bisset is so absolutely GORGEOUS in this movie, I'm certain I'd be content just watching her defrosting a freezer.

|

Jacqueline Bisset goes to Hades

In The Mephisto Waltz, we see that converting to Satanism requires considerably less formal instruction than converting to Christianity or Judaism |

As if that weren't enough,

there’s lovely Barbara Parkins (looking like a million bucks) cast in the kind

of femme fatale role her steely eyes and honeyed voice always hinted at (she would

have made a sensational Catwoman). She’s absolutely splendid and a great deal of fun to watch. Especially as her frequent bitch-fest scenes with Bisset

always seem on the verge of turning into a literal cat-fight which never materializes (I can dream,

can't I?).

Sticking out like a sore

thumb amongst all this portentous pulchritude is ol’ “Hawkeye” himself, Alan

Alda; looking for all the world like a film-school intern who’d wandered accidentally

in front of the camera. Alda has always seemed like a very nice guy to me, so I

won’t go on about how badly miscast I think he is (Bisset’s then-boyfriend, Michael

Sarrazin, would have been great in the role...or perhaps, Keir Dullea who was also very easy on the eyes), just suffice it to say that a huge chunk of plot credibility (pertaining to his sexual desirability) flies out the door every time he appears.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

I think one of the reasons I've never seen an occult film to ever come close to capturing Rosemary’s Baby’s intensity and efficacy is due to the fact that few of these films, once they latch onto their particular Satanic

gimmick, ever give much thought as to how the film might play to those who find it impossible to buy into the traditional concept of Satan. Polanski was smart enough to make his horror film as though he were constructing a paranoid psychological suspense thriller. It works because the structure

of the plot is viable whether you buy into the religious myth or not. In films like The Mephisto Waltz, the more implausible particulars of the occult gimmick in question (soul switching, in this case) are introduced so quickly that scant time is devoted to convincing us how otherwise practical characters come to believe in the inconceivable so swiftly.

|

Bad Romance

In his shot from the decadent New Year's Eve costume ball sequence, Alan Alda (in fez and monkey mask) and Barbara Parkins offer further proof that just about everything Lady Gaga does has been done before

|

Jacqueline Bisset’s Paula is far

too suspicious far too soon and it tips the hand of the plot. Likewise Myles’ swift,

unquestioning acceptance of Duncan’s largess. Alda’s character is such a blank

to us (we're given no sense of his values from the getgo, so we never know whether his abrupt acceptance by the jet-set crowd compromises them) that the eradication of his soul holds no dramatic weight. How

poignant his death would be were we afforded a sense of what it meant to him to reignite his abandoned music career. To know this would certainly inform our understanding of how his defeated

sense of self is flattered by the attentions of one as rich and successful as

Duncan Ely.

On a similar note, vis a vis the speed with which

The Mephisto Waltz speeds along its course, I’ve never seen the

death of a child in a movie given such short shrift. First off, Bisset looks

like

nobody’s mom on this planet,

least of all Pamelyn Ferdin, a child actress who seemed to be everywhere in the 70s (

What's The Matter With Helen?). Secondly, in

order to move things along as expeditiously as possible, Bisset's character, a mother whose only child dies suddenly and under mysterious circumstances, mourns for all of 24 hours before resuming her witch hunt and smoldering with desire for her husband. Whoever he is at this point.

In skimming over the human

drama, The Mephisto Waltz, like so

many other genre films, fails to give audiences sufficient time to become sufficiently engaged in the lives of the characters. A move that always winds up coming back to bite the film on the ass, undercutting, as it does, audience involvement in the outcome of the conflict.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

As an occult thriller, The Mephisto Waltz plays it pretty

straightforward down the line, telling its story crisply and entertainingly. That it doesn't always make the most of the possibilities posed by its bizarre story is, to me, the film's major setback. There's suspense and tension, but never

once is the film truly unsettling or disturbing. Certainly not as much as it could have been, given the fundamental

amorality of it all.

There’s a layer of a body-fetish/sex-addiction subplot lying below the surface of The

Mephisto Waltz’s soul-transplant theme that calls for a director attuned to

the revulsion/attraction of body horror…someone like David Cronenberg. The

fetish object in The Mephisto Waltz

is Myles Clarkson. Or his body, to be precise. Duncan Ely wants him for his youth, but specifically for his

hands. Roxanne wants her father, Duncan, and is willing to get to him through

the body of Clarkson. Most perverse of all, when Paula finally learns that her

husband is dead and that another man inhabits his body…it’s the body she

wants, and (to her own surprise) she doesn’t really care who's inhabiting it.

The film is awash with scenes

and dialog emphasizing Myles’ body and physical desirability, both before and

after its possession by Duncan:

Roxanne: (Ostensibly asking

Paula’s permission to make a life mask of Myles, but everybody knows what she's driving at) “It’s alright then, I can do

him?”

Abby: (To Paula about their

newly acquired dog) “He wants daddy.”

Paula: “Don’t we all.”

Paula's best friend: "Oh! He's sexy...don't you think he's sexy? You should know better than I!"

Roxanne's ex-husband, Bill (Bradford Dillman) to Paula after

she confesses that she still finds Myles sexually irresistible even

though she knows it isn’t truly him: “They say the truth is, once you've had one of

them [a Satan-worshipper] nothing

else will quite satisfy you.”

|

| Duncan will feel like a new man when he wakes up. Literally. |

With the utter disposability of

Myles, the man, contrasted with escalating battles for his body; the overarching

feeling you’re left with is that everybody loves Myles in parts, but not as a whole.

Kind of like a perverse corruption of Cole Porter’s song, “The Physician.”

There’s certainly nothing

wrong with having a story to tell and relaying it in as efficient and entertaining

a manner as possible. The Mephisto Waltz

succeeds on that score. But had it taken the time to explore the story’s

emotional and sub-textural themes…who knows? It might have been a genuine Rosemary’s Baby contender.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2011

.JPG)

.JPG)