"I am a camera with

its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking."

Christopher Isherwood

- The Berlin Stories 1945

I've wanted to see I Am

a Camera for 42 years. That's the length of time I've been aware of—yet

unable to lay eyes upon—this little-known, rarely-televised, not-available-on DVD, all-but-forgotten adaptation

of the successful Broadway play that inspired the Broadway & film musical Cabaret and gave the screen its very first Sally Bowles.

|

| Julie Harris as Sally Bowles |

|

| Laurence Harvey as Christopher Isherwood |

|

| Shelley Winters as Natalia Landauer |

|

| Anton Diffring as Fritz Wendel |

Forty-two years ago: It was 1972, I was a freshman in high

school, and Cabaret had just opened

nationally. I was eager to see the film on the strength of my fascination with Bob

Fosse's choreography in Sweet Charity

(1969) and my infatuation with Liza Minnelli in The Sterile Cuckoo (1969), but in order to persuade my family to select it

for a night out at the movies, I had to rely on the scores of critical raves

quoted in the newspaper ads. Which was all for the good because I knew next to nothing about just what Cabaret was.

I had absolutely no foreknowledge of Christopher Isherwood's 1945 novelized twin-memoir: The Berlin Stories;

I was in the dark about playwright John Van Druten (I Remember Mama) adapting one of those short novels—Goodbye to Berlin—into the 1951 play I Am a Camera (prompting theater critic Walter Kerr's terse, too-oft-quoted review, "Me no Leica"); and I was thoroughly

unaware that said seriocomic play had served as the structural source for the 1966 musical Cabaret…the original Broadway

production serving as merely the launchpad for Fosse's significantly

reworked movie adaptation.

Well, as if to prove the adage "ignorance is bliss," a byproduct of my state of unenlightenment was that it afforded me the rare opportunity of enjoying Cabaret free of the usual burdens that come with seeing a beloved stage and/or literary work adapted into another medium. That feeling of never fully being "in the moment" born of anticipating the omission or mishandling of some favored line or bit of business. Sometimes it's a ceaseless, almost involuntary process of comparison and sizing up which goes on in your head as you watch, hoping expectation doesn't outpace execution.

Well, as if to prove the adage "ignorance is bliss," a byproduct of my state of unenlightenment was that it afforded me the rare opportunity of enjoying Cabaret free of the usual burdens that come with seeing a beloved stage and/or literary work adapted into another medium. That feeling of never fully being "in the moment" born of anticipating the omission or mishandling of some favored line or bit of business. Sometimes it's a ceaseless, almost involuntary process of comparison and sizing up which goes on in your head as you watch, hoping expectation doesn't outpace execution.

|

| Lea Seidl as Fraulein Schneider, the landlady |

|

| Ron Randell as Clive Mortimer, the rich American playboy |

Like most everyone who saw it at the time, I was utterly blown away by Cabaret. Especially its stylish, darkly atmospheric depiction of the social and moral decay of pre-Nazi Germany in the '30s…so ideally suited to Bob Fosse's particular brand of razzle-dazzle cynicism. In an attempt to rectify my prior obliviousness, I subsequently took to reading everything I could about the film.

My first discovery was that it was the rare Cabaret review

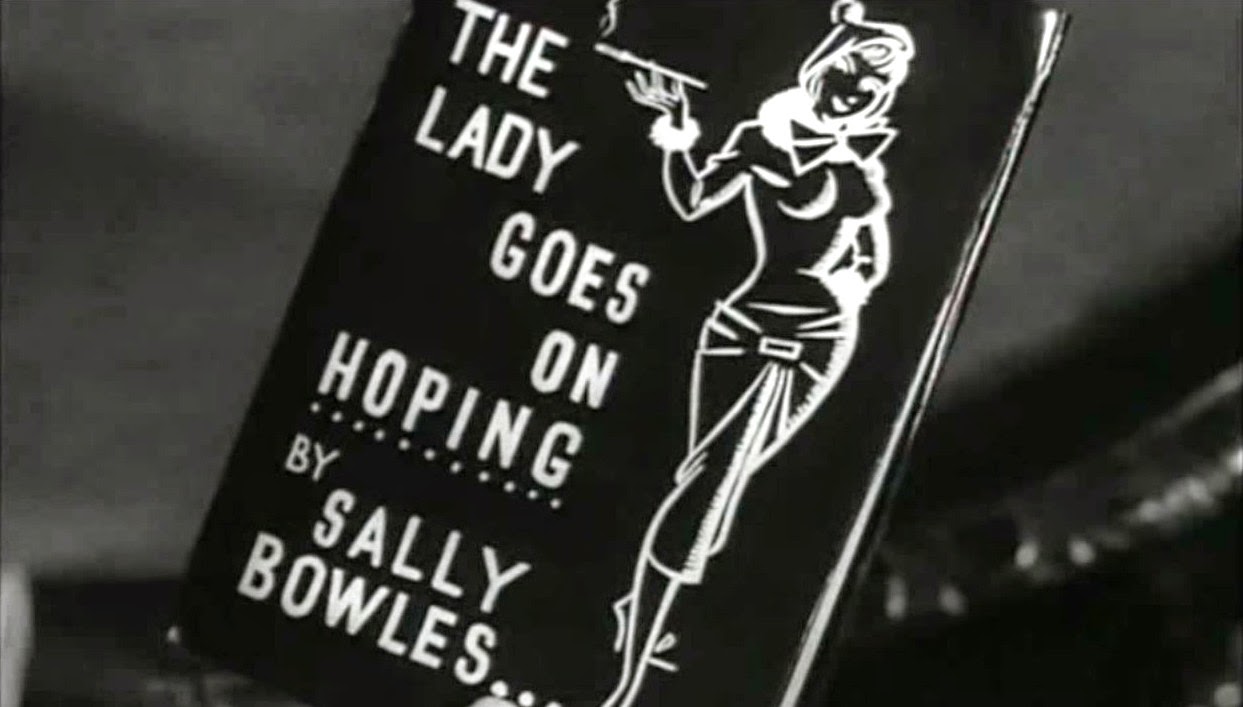

or feature article which didn't reference the film version of I am A Camera. Always unfavorably. Some remarked on the film's failure to do justice to Van Druten's play, others complained that it didn't successfully bring to life Isherwood's colorful characters, all cited it as the first on-screen incarnation of

Sally Bowles. While it definitely came as a surprise to me to learn that Fräulein Bowles

(who to this day is difficult to envision as anyone other than Liza Minnelli) appeared

on film a whopping 17 years before Cabaret

even existed, what really knocked me for a loop was that it was in the startlingly

against-type personage of Julie Harris.

I couldn't imagine two actresses with less in common than

Liza Minnelli and Julie Harris. Even in the most democratic of fantasies, I'm hard-pressed to envision any point at which the talents of these two very gifted ladies might intersect to make feasible the notion of their being cast in the same role. One's a jackhammer, the other a tap on the

shoulder. It piqued my interest no end to discover that it was Harris (an actress I adored, but always associated with reserved, Plain Jane roles like in The Haunting, East of Eden,

and You're a Big Boy Now) who originated the

role of one of literature's most flamboyant extroverts...and won

a Tony Award for it in the bargain!

|

| Divine Decadence Sally bares her emerald-green nails (and tigress snarl) |

Years passed (decades, actually), and I am A Camera eventually became one of those films (like Andy

Warhol's L'Amour) I resigned myself

to never seeing. Then, two weeks ago, just as I'd all but forgotten all about

it, what do you know?... there it was, big as life on YouTube!!!!

So it's true, good things come to those who wait...for a VERY long time!

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

Having read so little that was encouraging about I Am a Camera, I'm afraid that when the time came for me to finally see it, I did so more out of curiosity than conviction. After it was over, I wanted to give each of those early critics a solid trouncing over the head (myself included, for believing them), for to my great surprise, I found I Am a Camera to be a thorough and utter delight. Maybe I wouldn't have thought so back in 1972 when the air of solemnity Fosse brought to Cabaret rode the then-popular wave of pessimism of so many Nixon-era films (which flattered my adolescent self-seriousness); but today, I Am a Camera's unremittingly old-fashioned, studio-bound, almost farcical, light-comic approach distinguishes it so significantly from every other adaptation of Isherwood's memoirs I've seen, that it stands far and apart from comparison and represents to me, a work unique unto itself.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

Having read so little that was encouraging about I Am a Camera, I'm afraid that when the time came for me to finally see it, I did so more out of curiosity than conviction. After it was over, I wanted to give each of those early critics a solid trouncing over the head (myself included, for believing them), for to my great surprise, I found I Am a Camera to be a thorough and utter delight. Maybe I wouldn't have thought so back in 1972 when the air of solemnity Fosse brought to Cabaret rode the then-popular wave of pessimism of so many Nixon-era films (which flattered my adolescent self-seriousness); but today, I Am a Camera's unremittingly old-fashioned, studio-bound, almost farcical, light-comic approach distinguishes it so significantly from every other adaptation of Isherwood's memoirs I've seen, that it stands far and apart from comparison and represents to me, a work unique unto itself.

Presented in the form of an extended flashback told to fellow writing associates by "confirmed bachelor," now successful author Christopher Isherwood (Harvey), I Am a Camera recalls the years Isherwood spent as a struggling writer in Berlin in the 1930s. In vignette style, the film recounts his platonic, life-changing friendship with free-spirit Sally Bowles (Harris), a modestly talented cabaret singer and self-styled bohemian whose flighty manner and impulsive behavior propel him into adventures that ultimately serve as the basis and inspiration for his early writing successes. A subplot involving his only-slightly-worldlier friend, Fritz (Diffring), a would-be gigolo and closet Jew, wooing a department-store heiress (Winters), introduces a bit of drama and brings Germany's mounting Nazi threat to the forefront.

|

| The Nazi Intrusion Sally, Clive, and Christopher momentarily have their spirits dampened by a Jewish funeral procession |

I Am a Camera doesn't deviate significantly from the basic plot of Cabaret, its chief point of departure being merely one of approach. While Minnelli's Sally Bowles symbolized the kind of I'm-dancing-as-fast-as-I can, willful self-deception that allowed the Nazis to take over a Depression-era Germany by salving its sorrows with decadence. I Am a Camera presents Isherwood's adventures as a lighthearted coming-of-age story and depicts Bowles as something of an early incarnation of that genre staple: the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (thank you, Nathan Rabin) – the quirky, childlike female character who brings chaos into the orderly life of a sensitive, button-down type, only to leave him a better, more-matured artist for it.

Katherine Hepburn played one in Bringing Up Baby (1938), and so did Sandy Dennis in Sweet November (1968). Certainly, Minnelli's Pookie Adams from The Sterile Cuckoo qualifies (although the word "nightmare" might be more appropriate than dream), and the characters of Dolly Levi and Mame Dennis from Hello, Dolly! and Auntie Mame, respectively, are nothing if not the Manic Pixie Dream Matron. Of course, the great Grande Diva of Manic Pixie Dream Girls is Audrey Hepburn's Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany's, and ultimately it is this film, not Cabaret, which I Am a Camera most recalls.

PERFORMANCES

Whether or not one cares for I Am a Camera's lighthearted touch and bittersweet Hollywood happy

ending (which still feels more honest than making the Isherwood character bisexual

[the movie musical] or straight [the stage musical]), I can't imagine any fan of

classic cinema not being enchanted by the sight of so many brilliant dramatic actors displaying such a talent for comedy.

British actor Laurence Harvey, long a favorite of mine yet so

unaccountably stiff and affectless in so many of his American roles, is

appealingly naïf and boyish as Isherwood. I've always harbored a big crush on him, so perhaps I'm not exactly what you'd call an objective judge, but I'd easily rank his work in I Am a Camera alongside Room at

the Top and Expresso Bongo as among Harvey's best film performances.

|

| In a reversal of her role in 1951's A Place in the Sun, Shelley Winters plays an heiress wooed by a fortune-hunter |

As for the strikingly handsome Anton Diffring, so chilling

as the villain in Fahrenheit 451 and an actor who

literally made a career out of playing cold-hearted Nazis, I never would have

guessed he'd be so charming a light comedy player. Honestly, I think this

is the first film I've ever seen him smile! Several years away from the grating, undisciplined performances that would later brand her a camp film favorite, Shelley Winters has a surprisingly small role and displays a worrisome German accent, but she is endearing beyond belief. It's easy to forget what an accomplished comedienne she could be.

But hands-down, Julie Harris walks off with my highest praise. She's nothing short of sensational. I've seen Harris in many things over the years (even on Hollywood Squares, of all places), but I've never EVER seen her this perky and playful. I had no idea she could be such a flirtatious, funny, physical, and a vivacious personality. Her versatility is on full display here, capturing the many shades of Sally's mercurial personality, from her childlike vulnerability to her flashes of self-interested callousness. Speaking in that rapid-fire manner I associate with George Cukor movies, her Sally Bowles is less a bohemian iconoclast and reminds me more of Kathryn Hepburn's Eva Lovelace in Morning Glory (1933): all self-centered chatter and ostentatious show, but ultimately touching.

I found not a single moment of Harris' performance wanting, save for the poorly-matched dubbed singing voice she's given during her big cabaret number--the languid vocalist fails to capture the sprightliness of Harris' physical interpretation (I'm reminded of the too-calm dubbed voice attributed to Rita Moreno in West Side Story). Harris doesn't appear to be lip-syncing, leaving me to suspect the other voice was added post-production. i remember hearing Harris sing on the cast album of the 1965 Broadway musical Skyscraper ... she mostly went the Rex Harrison talk-sing route.

In the end, what pleased and surprised me most about Harris as Sally Bowles is the manner in which she tackles the role with such ease and command, inhabiting her character so winningly and completely that she resists comparisons to Liza Minnelli, making the part her own. No easy task, that.

.JPG) |

| "I remembered your eyes. It was as if they were asking me to look at you and yet not see you!" |

It's believed that Julie Harris' outstanding performance was overlooked for an Oscar nomination because I Am a Camera--a British production that failed to punish its sexually promiscuous heroine or delete mention of abortion--was denied a Production Code Seal, resulting in many theaters refusing to screen it, and some newspapers refusing to carry ads. In the UK, it was given the "Certificate X" rating.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

While devoid of anything like Cabaret's "bumsen" scene, I Am a Camera is remarkably frank on the topics of sex, abortion, prostitution, and, depending on one's susceptibility to gay coding in old films, homosexuality. Considered risqué for its time, I was amused by just how much they were able to allude to in this 1955 film (a gay couple is briefly glimpsed in the nightclub scene) and enjoyed noting how many little details of style and content would later show up in Fosse's Cabaret.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

.JPG) |

| This Sally sings at The Lady Windermere, but its clientele is pure Kit Kat Klub, as are its wall caricatures |

.JPG) |

| Partaking of Sally's favorite pick-me-up: Prairie Oysters |

|

| The Threesome... |

|

| ...The Twosome |

|

| Laurence Harvey + rectal thermometer = sexiest scene in the film |

|

| "I mean, I may not be absolutely exactly what some people call a virgin... ." |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

For all the charismatic dominance of

Sally Bowles and Julie Harris' standout performance, I Am a Camera ultimately manages to make good on its first-person

title by being a story of one man's coming of age. The increased presence of

the Nazis in Berlin challenges Isherwood's determination to just be a spectator in life, his ultimate inability to ignore its evil facilitates his growth as both a man and an artist.

For me, the poignancy of I Am a Camera is found in its final moments when it becomes clear (to us, if not the characters involved) that, like Dorothy in The

Wizard of Oz, Christopher has possessed all along what he'd sought to find. As the only person to take pity on the abandoned Sally that first night in the

club; to be the one individual who offered her shelter without the want of anything in return;

to have remained by her side during a crisis, even going so far as to propose marriage

and lose a promising job opportunity--Christopher was an "involved" participant in life from the very start. He was never for a moment the apathetic,

unthinking "camera" he imagined himself to be.

.JPG) |

| Christopher ceases being the passive observer |

Author Armistead Maupin in his 2008

introduction to Christopher Isherwood's

The Berlin Stories (and if you

haven't read The Berlin Stories, I highly

recommend it), makes the observation that Isherwood's narrative device of assuming the

role of the "camera" in his memoirs--the impartial, uninvolved recorder

of events--was the author's way of protecting himself. A method of intentionally keeping

his homosexuality out of his autobiographical stories for fear that its mere

inclusion would distract from everything else in the text.

A necessity at the time, but one

rectified by Isherwood himself in his 1976 memoir Christopher and His Kind, in

which the very same pre-war Berlin years documented in this film are recounted

with a proud acceptance of his sexuality and an acknowledgment of its profound influence

on his life and his art.

I Am a Camera; a film shrouded in period-mandated gay coding (the aforementioned "confirmed bachelor" line) and starring a closeted gay actor portraying an asexual/sexually ambiguous character; is a product of its time, yet nevertheless contains a timeless message. Especially for the LGBTQ community, which has been so much a part of Christopher Isherwood's enduring legacy. Society, when not actively seeking to eradicate, has always encouraged gay people to "hide in plain sight." To, in effect, protect ourselves through anonymity and the acceptance of a non-participatory role as a "camera" on the periphery of life.

I Am a Camera - (inadvertently perhaps, but I'd like to think by way of the innate humanity of Isherwood and his characters)--exposes inauthenticity as an obstruction to growth (Sally, a woman defined by artifice, never changes). It promotes the necessity of being true to oneself (Fritz finds love and is compelled to reveal his true self to Natalia), and it affirms the absolute necessity that we must all be active participants in life...no matter how complicated things become.

Since I consider Bob Fosse's Cabaret to be such a perfect film and wasn't really hoping to find a movie to compare it to or replace it with, I rejoiced in I Am a Camera turning out to be so comprehensively and refreshingly different. Making up for those 42 years of longing, I've already seen it three times and marvel at what a splendid lost gem it is. To quote Sally Bowles, I think I Am a Camera is "Most strange and extraordinary!"BONUS MATERIAL

The tune Sally Bowles sings in her cabaret act is the 1951 German song, "Ich Hab Noch Einen Koffer in Berlin" (I Still Have a Suitcase in Berlin), written by Ralph Maria Siegel. In this film, the song is given new English lyrics by Paul Dehn, the title changing to: "I Saw Him in a Café in Berlin."

You can Hear Marlene Dietrich sing the original song HERE.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2014

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)