This all calls to mind Francis Ford Coppola’s ambitious but flawed dream project, One from the Heart, which was dubbed “Coppola’s Folly” on release, and the irony that its creation was instrumental in the demise of that other Coppola dream: his American Zoetrope Studios. As someone who came of age and developed a love for movies during the youth-centric, formative years of the New Hollywood, out of which Coppola emerged (roughly 1967 to 1979), I've discovered that one of the more sobering realities of aging has been bearing witness to what’s become of the ideals and ambitions of the golden boys of the Hollywood Renaissance.

|

| Francis Ford Coppola takes an ordinary couple and places them in an extraordinary, fantasy vision of Las Vegas |

George Lucas, the once-venturesome director of the lively American Graffiti, now seems a virtual prisoner of his own success, holed up at Skywalker Ranch like Charles Foster Kane in Xanadu, content to spend his days endlessly tweaking and re-tweaking the same movie. Film geek Peter Bogdanovich, after a couple of ill-fated Svengali episodes, reached creative stasis once he exhausted his fan-boy catalog of borrowed film styles. Martin Scorsese is making kids’ films to stay relevant. And Steven Spielberg, always more a company man than a maverick, has emerged as more quotidian and old-guard than the most journeyman of filmmakers from the rigid days of the studio system.

Of all the directors of the era, the trajectory of director

Francis Ford Coppola’s career is perhaps most indicative of what was right

(individualistic, innovative, artistic) and wrong (arrogant, undisciplined,

insulated, and out-of-touch) with the American New Wave in cinema of the '70s. His Godfather films (1972 & 1974) and Apocalypse Now (1979) all made good

on the movement’s assertion that commercial film was a viable medium for artistic

and personal expression. Among that film-school breed who proffered themselves as the worthy heir to the throne of the deposed moguls of yesteryear, Coppola alone seemed to possess the requisite business smarts and creative vision to see it through. Or so it seemed.

Throughout his career, Coppola has spoken out (exhaustively)

about the levels of studio interference he’s had to battle in order to get his

films made. His unparalleled track record of critical and commercial successes

only seemed to confirm his contention that meddlesome studio heads were the

enemies of art.

When, in 1980, Coppola purchased Hollywood General Studios to form

his own, independent motion picture studio—American Zoetrope—it was the realization

of a groundbreaking New Hollywood ideal: a space to make films independent of the

interference of the Hollywood money men.

Oh, but that Coppola could have had such interference.

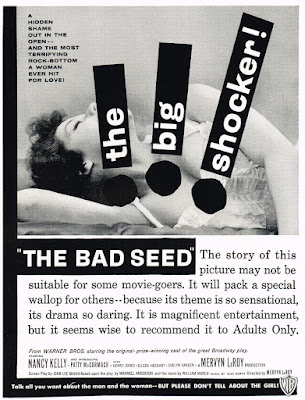

As the studio’s debut feature, Coppola envisioned a simple, old-fashioned

Hollywood musical given a modern twist through the employment of cutting-edge digital

filmmaking innovations Coppola would come to dub “Electronic Cinema.” This allegedly

creativity-enhancing/money-saving innovation proved no match for a

director who couldn't grasp that technology fetishism is never a viable

substitute for basic storytelling skills.

|

| Teri Garr as Frannie |

|

| Frederic Forrest as Hank |

|

| Nastassja Kinski as Leila |

|

| Raul Julia as Ray |

Story: Frannie works at a travel agency while Hank is the co-owner of an auto junkyard. After five years together, on the eve of their July 4th anniversary, the couple finds themselves at a romantic crossroads: she

wants adventure, he wants stability. How each works through their respective five-year

itches is beautifully rendered in a meticulously recreated Las Vegas (everything

was shot on the Hollywood sound stages), but the content never measures up to the presentation.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

THE AUTOGRAPH FILES

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2012

.JPG) |

| Lainie Kazan as Maggie |

It’s my guess that One

from the Heart, in all its brobdingnagian excess, is attempting to comment

on the transformative power of love and its ability to make even the most unprepossessing

of souls feel as though they have suddenly stepped into one of those lushly

romantic, old-fashioned MGM musicals. A charming idea, conceptually

speaking, that holds a great deal of potential. It’s only in the practical

application that things start to hit a snag. Where a feather-light touch and

considerable wit are required for this kind of material, One from the Heart keeps tripping over its own intentions because

Coppola’s directorial approach to tender matters of the heart is to pound you

over the head with his tinker-toy infatuation with the technological.

To anyone who has ever actually experienced the pains and

joys of life, love, and romance, it’s plain that the only intensely felt

passions on display in One from the Heart

are the hots Francis Ford Coppola has for his “Electronic Cinema” gadgetry. A

prime example of a man so lost in an onanistic orgy of film love that, $23

million later, he failed to even notice that he hadn’t yet made a

movie.

|

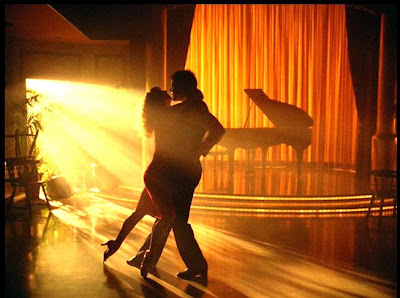

| Frannie finds her idealized vision of romance in singing (and apparently dancing) waiter, Ray |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT

THIS FILM

By 1982, bad word of mouth preceding the release of a

Francis Ford Coppola film was as common an occurrence as an appearance by Charo

on The Love Boat. From The Godfather to Apocalypse Now, Coppola seemed to willfully perpetuate the image of

himself as the wild cannon maverick who could pull a masterpiece out of the

ashes of months of troubled production rumors and bad press. It’s in light of

all this that Coppola’s long-held assertion that One

from the Heart didn’t get a fair shake from the press has never quite rang true.

I remember being among the throngs of people clogging the

streets of Westwood Village in Los Angeles, excited beyond all reason at the

prospect of getting a pre-release glimpse of One from the Heart in January of 1982. The crowd was abuzz, each of

us parroting to the other Coppola’s rhetoric hype about being eyewitnesses to the

beginning of a new era in filmmaking.

As is typical at these kinds of preview screenings, a

general atmosphere of “The Emperor’s New Clothes” takes over, and everybody loves

EVERYTHING. Each set, dissolve, and digital camera trick was greeted with thunderous

applause (in part, I suspect, because we all thought Coppola was somewhere in the

audience), and we were all convinced that we were watching the Citizen Kane of the '80s. It wasn’t until

I was walking back to my car that I realized that all of my laughter had been forced,

all of my emotional responses self-generated; and though dazzled by the visuals, a great many of the much-touted innovations were, in reality, age-old theatrical stage effects (walls dissolving, color fades).

I love romantic movies, and anyone who knows me knows that I'm a sentimental slob who cries at the drop of a hat...and yet the only sequence that brought forth waterworks was the finale…and

even that was due more to the still-touching-to-me instrumental theme "Take Me Home," arranged to sound like a child’s music box.

Reluctantly, I had to admit that all of my positive feelings

about One from the Heart were keyed

in to my anticipation of the project and to the artistic potential Coppola’s candy-colored confection

presented. One from the Heart’s

visuals and technology were indeed impressive, but as evidenced by the audience’s

meeting each display of cinema magic with a round of applause; none of us got lost

in the magic enough to stop taking notice of it. Shades of Martin Scorsese’s New York, New York!

There are many stunning, musical-friendly images in One From the Heart.

I only wish someone who knew how to make a musical were directing.

PERFORMANCES

The structure of a great many musicals is to have at

their center, incredibly ordinary, if not downright dull characters (e.g., Bells are Ringing, Sweet Charity, On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, Oklahoma) who find their lives magically transformed by love. However, few, if any, of the people

involved in the making of these movies have ever been so ill-advised as to actually cast

dull, ordinary people in these roles. Both Frederic Forrest and Teri Garr are

wonderful, talented character actors, but neither has the requisite something (star-quality?) to

make watching them more interesting than, say, spying on my neighbors over the

back fence. (Imagine the 1949 Stanley Donen musical, On the Town, with the emphasis placed on the Ann Miller/Jules Munshin romance instead of Gene Kelly and Vera Ellen.)

Hammering home the obviousness of this fact are One from the Heart’s stupendously

charismatic co-stars, Nastassja Kinski and Raul Julia. Both actors have in

abundance what the film’s leads lack: screen presence. I kept wishing the story

would somehow shift gears and magically become a love story about the circus

girl and singing waiter.

|

| Harry Dean Stanton as Moe |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

For good reason, this blog isn’t titled “Levelheadedness is

What Le Cinema is For…”, because movies, like dreams, have this ability to get

to us on so many different levels…even when said dream or movie doesn’t make a

lick of sense. By the same alchemy that interprets movement from still images

flickering past one’s eyes at 24-frames per second (precisely the way a

zoetrope works, the magic lantern device from which Coppola’s production

company derives its name), One from the

Heart’s almost non-stop flashes of technical brilliance do much to mitigate

the emotional hollowness at the center of the whole enterprise. The shimmering images Coppola

devises for One from the Heart enchant

in a way not dissimilar to mentally flipping through an expensive coffee table

book on photography; beauty in no need of context.

|

| Fanciful imagery abounds: Hank finds his romantic ideal in circus performer, Leila - here seen dancing in a giant martini glass |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

When it all began, the New Hollywood presented itself as the

antidote to the bloated, outmoded assembly-line methods of studio-system filmmaking.

With minimal budgets but ingenuity and talent to spare, a veritable army of

young and enthusiastic movie-makers succeeded for a time in rejuvenating

American motion pictures in a way we will likely never see again.

Unfortunately, success begat money, money was met with unbridled

freedom, and with freedom came arrogance, a lack of discipline, and even respect

for the principles that inspired the revolution in the first place. Directors, once up in arms over the fact that the budget for a single overinflated bomb like Paint Your Wagon ($20 million) could have financed 20 smaller, perhaps better films, themselves nearly brought the industry to its knees through their own ego-driven excesses.

Of all the golden boys who imploded when given a big budget and free rein (Michael Cimino -Heaven’s Gate, Stephen Spielberg – 1941, Martin Scorsese - New York, New York), it can at least be said of Francis Ford Coppola that he bankrupted his own studio and wasted his own money.

Clip from "One From the Heart" (1982)

The version of One

from the Heart currently available on DVD has been re-edited and is a tighter, and in some ways, better film than the one I saw

in previews back in 1982. Alas, there’s just no getting past the fact that this

neon heart has no real pulse. One from

the Heart feels like a film made by someone who knows an awful lot about movies, but not much about life.

|

| One from the Heart would have benefited greatly from the intimacy Coppola brought to The Conversation. Instead, this simple romance was handled with the bombast and overkill of Apocalypse Now |

Today, One from the Heart still thrills me as eye candy and pleases with its sometimes hauntingly beautiful jazz-tinged score, but in an odd way, it offends me for its epic waste.

In TheTowering Inferno, Paul Newman says of the smoldering shell of the skyscraper that needlessly took the lives of so many: “I don’t know. Maybe they ought to just leave it the way it is. Kind of a shrine to all the bullshit in the world.”

In TheTowering Inferno, Paul Newman says of the smoldering shell of the skyscraper that needlessly took the lives of so many: “I don’t know. Maybe they ought to just leave it the way it is. Kind of a shrine to all the bullshit in the world.”

Maybe that’s One from

the Heart’s ultimate merit: it stands as a melancholy shrine to all the tarnished optimism and corrupted ideals of the Hollywood New Wave of the '70s.

THE AUTOGRAPH FILES

|

| Teri Garr autograph from when I was working at a bookstore on Sunset Blvd. |

|

| Harry Dean Stanton autograph I got when he came to the Honda dealership where I used to work |

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2012

.jpg)

.jpg)