The generic Hollywood “woman’s film,” those melodramatic,

get-out-your-handkerchiefs – style weepies that were once Joan Crawford’s and

Bette Davis’ stock in trade, underwent a colorful (that is to say, increasingly

explicit) transformation during the '50s and '60s. Reflecting the changing role

of women in American culture, the once romance-centric genre transmogrified

into the multi-character, hand-wringing, career-girl soap operas of the sort

typified by Rona Jaffe’s water cooler drama The Best of Everything (1956), in which Joan Crawford’s stock '40s

shopgirl character gets an executive upgrade, and that deservedly iconic ode to

Broadway, booze, and barbiturates, Valleyof the Dolls (1967).

These films dramatized, in highly glamorized fashion, the challenges facing women as they strove to balance love, friendship, and the pursuit of their dreams while navigating the patriarchally hostile waters of the American workforce. Always purporting to “blow the lid off” one taboo subject or another (in George Cukor’s The Chapman Report it was the sex lives of suburban housewives) these films offered at most a cursory nod to female independence before reverting to type and getting back to the business of subtly endorsing traditional gender roles.

A standout, both appearance and character-wise, is Jessica Walter, who either annoys or enchants in a showy role that is essentially Rosalind Russell in The Women. Also very good is the highly appealing Shirley Knight. My personal favorite, however, is Joan Hackett (making her film debut along with Bergen and Pettet) whom I never tire of watching and who never seems to hit a false note.

Before I finish, special mention must be made of the men in The Group. True to the genre, the men are a pretty odious bunch. Almost to a man they are characterized as weak, bigoted, manipulative, oppressive, brutalizing, or womanizing. Some all at the same time. This is of course to be expected and goes with the soap opera territory. What surprises me most is that there isn’t a single looker in the bunch. I know it’s a matter of taste and I'm taking into account that perhaps in 1966 these guys passed for handsome (so what was Paul Newman?); but to a most distracting degree, the men at the center of The Group are like a grandmother’s wish-list of desirable males. Hal Holbrook? Larry Hagman? Richard Mulligan? James Broderick? The film features such a parade of sexless, daddy-fixation types that after a while I actually started to take it as some kind of personal affront. Valley of the Dolls suffered from the same malady.

These films dramatized, in highly glamorized fashion, the challenges facing women as they strove to balance love, friendship, and the pursuit of their dreams while navigating the patriarchally hostile waters of the American workforce. Always purporting to “blow the lid off” one taboo subject or another (in George Cukor’s The Chapman Report it was the sex lives of suburban housewives) these films offered at most a cursory nod to female independence before reverting to type and getting back to the business of subtly endorsing traditional gender roles.

Valley of the Dolls, in its exquisite awfulness, remains the

gold standard by which every “sex and soap” women’s film is and should be

compared. But one of my favorite forgotten examples of the genre that managed

to fall through the cracks due to past unavailability (it had a brief VHS life [Thanks, Poseidon3!], was never released on Laserdisc, but is currently available on made-to-order DVD) is Sidney

Lumet’s lively screen adaptation of Mary McCarthy’s 1963 bestselling novel, The Group.

|

| Eight is Enough The sparkling cast of up-and-comers that comprise The Group |

I don’t know who first coined the phrase “superior soap opera”

but the term categorically applies to this expensively mounted, surprisingly well-acted

tale of the interweaving lives of eight friends—graduates of Vassar College,

Class of ’33— as each sets out to make her mark on the world. The experiences of these economically and psychologically

diverse heroines reflect, in microcosm, the emergent state of (white) American womanhood

in the mid-20th century. Specifically, the Roosevelt Administration years

from The Great Depression through to the earliest days of the outbreak of WW

II.

As each woman embarks on the journey of realizing the American Dream that their wealth, position, and privilege have practically guaranteed them, they discover that life outside the protective bubble of college and "The Group" poses considerably greater challenges.

As each woman embarks on the journey of realizing the American Dream that their wealth, position, and privilege have practically guaranteed them, they discover that life outside the protective bubble of college and "The Group" poses considerably greater challenges.

With a cast of eight beautiful women all falling histrionically

in and out of love, bedrooms, and careers, The

Group basically takes the usual all-girl triad formula of The Pleasure Seekers and Three Coins in the Fountain (along with the aforementioned

The Best of Everything and Valley of the Dolls) and merely ratchets up the stakes by moving it into territory first blazed by Clare Boothe Luce in The Women. All of which is sheer Nirvana for fans of camp cinema

and movies about high-born women brought to low circumstances, but a headache

for studio publicity departments and folks seeking economic ways of recounting the

plot and summarizing the characters.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

PERFORMANCES

The challenge presented in having to promote a film with an

ensemble cast of relative unknowns is revealed in the giggle-inducing tone

adopted by the film’s ad campaign; the copy of which I’ll borrow to briefly

introduce the members of The Group:

Lakey: The Mona Lisa of the smoking-room…for women only!

Dottie: Thin women are more sensual. The nerve endings are

closer to the surface.

Priss: She fell in love and lived to be an “experiment.”

Polly: No money…no glamour…no defenses…poor Cinderella.

Kay: The “outsider” at an Ivy League Ball.

Pokey: Skin plumped full of oysters…money, money, money…yum,

yum, yum!

Libby: A big scar on her face called a mouth.

Helena: Many women do without sex, and thrive on it.

If I remember correctly, most, if not all of these lines come

directly from the novel (a terrific read, I might add) and several are even repeated

in the film. How anyone was able to resist such sleazily salacious come-ons is beyond

me, but The Group didn’t fare too

well at the boxoffice at the time and slipped quietly into obscurity after

that. My guess is that it’s because the film at its core wasn’t really as trashy as its hard-sell. Well, more’s the pity, for The

Group, by benefit of its remarkable cast and director Sidney Lumet’s deft

handling of the wide-sweeping plot, is a step above the usual glossy soap opera.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

As a fan of both Robert Altman’s trademark ensemble opuses and movies

with overdressed women dramatically suffering in opulent surroundings, there

isn’t really much to dislike about The

Group. Touching on everything from politics, birth-control, lesbianism, marriage,

mental illness, spousal abuse, adultery, childbirth, alcoholism, and date-rape

(all in the course of 2 ½ hours) The

Group has a lot of field to cover. Director Sidney Lumet (The Pawnbroker, Network, Dog Day Afternoon)

keeps things moving at a rapid-fire pace that adds spark to the light comedy

(Jessica Walter is a hoot as a bitchily gabby gossip) and tension to the drama.

If the expeditious pacing of the story spares The

Group from ever being plodding or dull, it's fair to say it also occasionally undercuts the film’s overall emotional

impact. The commitment to brevity that results in Joan

Hackett’s character disappearing for a protracted time in the middle of the film is a considerable flaw as far as I'm concerned, but at least it’s a flaw born of an attempt to tighten the sprawling narrative.

|

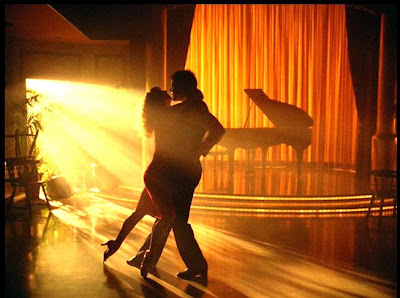

| An example of Sidney Lumet's masterful framing and use of space in The Group |

I generally just like the propulsive feel of The Group's visual style. I can’t

remember when I’ve seen a movie that handled the staging and filming of group

scenes better or to greater effect; nor can I recall a cleverer employment of cinematic

devices to provide plot exposition. In rewatching the film, my attention is

drawn to the many subtle character interactions and small details (like the financially-struggling Kay always wearing the same hat to every wedding) easily overlooked

on first viewing due to the film’s quick cutting and Lumet’s skillful use of the foregrounds and backgrounds to relay information.

When I think of what I like about The Group, the conclusion I always arrive at is, what’s not to like?

|

| The telephone features prominently in The Group not only as a means by which the friends stay in contact but as a handy device to relate plot exposition |

PERFORMANCES

If you’ve ever harbored the notion that a film like, say, Valley of the Dolls would have been “better”

with real actresses in the roles (sorry Patty Duke), watching The Group should pretty much lay that fantasy to rest. The cast assembled

for The Group couldn’t be more

accomplished or better-suited to their roles, but even they can’t surmount a

screenplay or a basic story construct so plot-driven. The mere volume and

frequency of crises and conflict in films like these reduce even exemplary

performances (Hackett, Knight, Pettet, and Hartman) to “best of” moments.

|

| Sidney Lumet cast his father, Baruch Lumet in the small role of Mr. Schneider, Polly's paternal neighbor |

A standout, both appearance and character-wise, is Jessica Walter, who either annoys or enchants in a showy role that is essentially Rosalind Russell in The Women. Also very good is the highly appealing Shirley Knight. My personal favorite, however, is Joan Hackett (making her film debut along with Bergen and Pettet) whom I never tire of watching and who never seems to hit a false note.

Before I finish, special mention must be made of the men in The Group. True to the genre, the men are a pretty odious bunch. Almost to a man they are characterized as weak, bigoted, manipulative, oppressive, brutalizing, or womanizing. Some all at the same time. This is of course to be expected and goes with the soap opera territory. What surprises me most is that there isn’t a single looker in the bunch. I know it’s a matter of taste and I'm taking into account that perhaps in 1966 these guys passed for handsome (so what was Paul Newman?); but to a most distracting degree, the men at the center of The Group are like a grandmother’s wish-list of desirable males. Hal Holbrook? Larry Hagman? Richard Mulligan? James Broderick? The film features such a parade of sexless, daddy-fixation types that after a while I actually started to take it as some kind of personal affront. Valley of the Dolls suffered from the same malady.

|

| No, this isn't an image of Polly (Shirley Knight) and her father. This is Gus (Hal Holbrook) the patently implausible object of desire of two gorgeous women and one unseen wife in The Group |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

My older sister (whom I credit/blame for a good deal of my love of bad movies) got me to watch The Group on TV with her when I was a kid. A protofeminist if ever there was one, she tended to gravitate towards movies with female protagonists but lamented the fact that a great majority of these films tended to be vaguely masochistic soaps and cheesy exploitation films.

My older sister (whom I credit/blame for a good deal of my love of bad movies) got me to watch The Group on TV with her when I was a kid. A protofeminist if ever there was one, she tended to gravitate towards movies with female protagonists but lamented the fact that a great majority of these films tended to be vaguely masochistic soaps and cheesy exploitation films.

My sister (who was drawn to the bitchiness of the Libby character

but identified with the self-sacrificing nobility of Polly) enjoyed the camp

fun to be had at the expense of the fancy clothes, elaborate hairstyles, and frankly unsympathetic

milieu of the privileged classes; but what she also responded to, and in turn helped

me to appreciate, was what the film was trying to say about the challenges of maturity. The idealized vision of the world (and oneself) one can safely harbor while sheltered within the walls of youth and academia can take quite a beating when confronted by the disappointments and compromises of the real world. Is a person really failing in life if they put to rest youthful dreams in hopes of achieving some unforeseen, yet perhaps more authentic, realization of fulfillment? And how much pain does one cause oneself clinging to idealized illusions of "potential" and entitled success...all the while ignoring the possibility for happiness dressed in humbler clothing?

Have to hand it to my sister...if she could find that kind of insight within a glossy potboiler like this, I'd say I learned about the value of "bad" films at the feet of a master.

|

| In a role rendered considerably smaller in the film than in the book, Carrie Nye has at least one memorable scene as Norine, a low-income Vassar classmate and outsider excluded from The Group |

Now, I’m not going to make out like The Group is some kind of profound, unacknowledged classic, but in light of what women's films have become over the years (they proudly proclaim themselves "chick flicks" and celebrate shopping as a valid expression of female empowerment), and in our current boomerang culture that doesn't encourage young people to seek and accept struggle as an integral part of the growing-up process; well...let's just say that there's something to be said for a 46-year-old guilty-pleasure movie that comes across as more progressive and perceptive in 2012 than it did in the year of its original release.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2012

.JPG)