When the lesbian proprietress

of a seedy, by-the-hour hotel in Harlem says to a character: “If anybody can

raise the dead and make ‘em pay their rent, it’s you,” you don't doubt it for a minute.

Not when the character in

question is Imabelle, a voluptuous gangster’s moll from Mississippi with brains, resilience, and a gift

for self-preservation. She's also the possessor of $200,000 in stolen gold ore stashed in a trunk at the train station, and, as embodied (accent on body) by the luminous Robin Givens, we know from first sight that Imabelle is a woman who, with very little effort, could and would re-resurrect Jesus for the sole purpose of paying her hotel tab.

|

| Forest Whitaker as Jackson |

|

| Robin Givens as Imabelle |

|

| Gregory Hines as Goldy /Sherman |

|

| Danny Glover as Easy Money |

A Rage in

Harlem is a Black film

noir set in the 1950s. A smolderingly romantic, double-cross crime caper of mortuary-black

comedy rich in period detail, vividly-realized off-beat characters, colorful dialogue,

and an unnerving propensity to erupt into swift and sudden outbursts of violence.

Although I was a bit late in happening upon this gem (a radiant rough diamond)

and missed out during its original release, it has become a lasting favorite of mine and is a film I rank as one of the most stylishly entertaining unsung greats of

‘90s cinema.

|

| "If Christ knew what kind of Christians he had up here in Harlem, he'd climb back up on the cross and start over." Helen Martin as Mrs. Canfield |

The feature film directing debut of actor Bill Duke (Car Wash, American Gigolo), A Rage in Harlem is a pitch-perfect, very loose adaptation of the gritty 1957 novel by African-American author Chester Himes. Originally and more aptly titled For Love of Imabelle, A Rage in Harlem is Himes’ first entry in his nine-volume “Harlem Detective” series highlighting the blood-soaked exploits of detectives “Coffin” Ed Johnson and “Grave Digger” Jones. Of the three Chester Himes "Harlem Cycle" books adapted to the screen, A Rage in Harlem is the only one to retain the novel’s late-‘50s period setting. In their first screen incarnations, Himes’ hardboiled and consistently brutal detectives were updated as tough-talking defenders of Harlem justice during the Black Power ‘70s in the films Cotton Comes to Harlem - 1970 and Come Back Charleston Blue – 1972, both starring Raymond St. Jacques and Godfrey Cambridge.

|

| Raymond St. Jacques as Coffin Ed Johnson and Godfrey Cambridge as Grave Digger Jones in Cotton Comes to Harlem |

|

| Stack Pierce as Coffin Ed Johnson and George Wallace as Grave Digger Jones in A Rage in Harlem |

A Rage in

Harlem, which could easily

be subtitled Gold Comes to Harlem, is set in 1956 and begins in a dilapidated

shack in Natchez, Mississippi where a ragtag band of swindlers has pulled off

the formidable feat of robbing a gold mine and netting some $200,000 in gold

ore…at the cost of a few dead bodies. That the robbers are all Black (Slim, Imabelle,

Jodie, and Tony) and the victims were white is of no small consequence in the nasty way things play out when a local redneck and his goons decide to renege

on their deal to fence the goods for their market value.

But after the smoke clears from the ensuing bloody melee, Imabelle, and the gold are nowhere

to be found. Managing to escape without learning the fate of her fellow gang

members—and not losing any sleep over it—Imabelle hightails

it to New York in search of Easy Money. Easy Money being the Harlem crime boss (Danny

Glover) capable of turning her trunkful of difficult-to-transport gold into infinitely

more cartable cash.

|

| Three Cons and a Pro Slim (Badja Djola), Imabelle (Givens), Jodie (John Toles-Bey), and Tony (Ron Taylor) |

When circumstances

beyond her control (namely, Easy Money’s arrest) oblige Imabelle to stick

around Harlem longer than anticipated, the penniless purloiner seizes on a plan

to nab herself an easy mark who’ll put her up while awaiting Easy Money’s

release. Luckily for Imabelle, nowhere in all of Harlem is there to be found a

mark easier than Jackson (Forest Whittaker); a roly-poly, devoutly religious mortuary

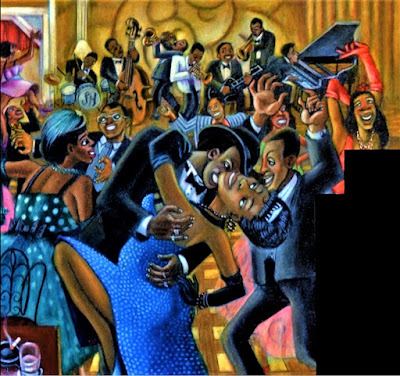

employee so sincere and unsophisticated, he even gets heckled by little old ladies. Imabelle's seduction of the guileless Jackson confirms her as the story's irresistible force (she puts the moves on him at the Annual Undertaker’s Ball while Screamin’ Jay Hawkins performs--appropriately enough--his 1956 hit “I Put a Spell on You”). But it’s Jackson’s unwavering decency and

gentle heart that proves to be the immovable object that ultimately comes to melt Imabelle’s

implacable heart, if not necessarily her larcenous soul. Something’s gotta

give.

|

| Pious Jackson takes the worldly Imabelle to Church |

|

| Goldy and Big Kathy watch as Jackson proceeds to make a shambles of their well-plotted sting |

Matters aren’t helped by the fact that throughout, Imabelle’s motives and loyalties remain exasperatingly abstruse, or that the law enforcement efforts of detectives Coffin Ed and Grave Digger have a tendency of making already bad situations much, much worse. This combustible mixture of head-over-heels romance crossed with the passionate impulses inspired by gold, greed, and guns may seem like the traditional stuff of noir and crime fiction; but in a place like Harlem and in the form of a felonious femme fatale like Imabelle, bad has never looked so good.

|

| Devil in a Blue Dress |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS MOVIE

I’m a big fan of film noir, but my fondness for crime fiction and sagas

about hardboiled detectives hasn’t exactly extended to the printed page. I’ve read very few detective

novels in my time, so I’m certain there are exceptions, but my personal

experience of these books has been that while I admire the writing, I tend to

be less enthusiastic about the genre-mandated machismo, sadism, and misogyny. Sure,

these same elements are present in the film noirs I love, but their severity is

softened considerably by Hays Code interference, expressionism, and Linda

Darnell.

My aversion to

the kind of unfiltered, in-your-face kind of violence I associate with crime

novels is why—save for a childhood memory of thumbing through my father’s paperback

copy of “Blind Man With a Pistol” to see if there were any dirty parts (published

1969, it’s the last complete book in Himes’ Harlem Detective series)—the sole Chester

Himes novel I’ve read to date is “A Rage in Harlem.” I got a copy of Himes’ book back sometime in

the mid-‘90s not long after seeing A Rage in Harlem for the first time on

cable TV. Then my mind was still reeling from the film’s snazzy, humorously stylized

vision of mid-century Harlem and its Runyonesque

denizens, and my curiosity high to find out if the novel pleasures could any

way live up to the delights I found in the film.

What first struck me while reading “A Rage in Harlem” is that it would be difficult to overstate Chester Himes’ brilliance as an author and a storyteller. Even as I found myself dreading turning the page for fear of some graphically-described act of brutality catching me off guard, there was no mistaking that Himes’ characters and way with words (his descriptive dialogue, much of it laugh-out-loud funny, fairly leaps out at you) makes NOT turning the page a complete impossibility.

The second was discovering to what degree the movie adaptation had expanded upon and deviated from the source novel. I was surprised to find that Imabelle doesn’t figure nearly as much in the book as she does in the film. She’s discussed, fetishized, and obsessed about to the point that her presence is felt throughout, but she’s barely a main player in a narrative largely set into motion by her actions.

Then there was the surprising discovery that the entirety of the novel’s storyline only accounts for about a third of the plot of the film... the middle of it, yet! First-time screenwriters John Toles-Bey & Bobby Crawford (the former appearing in the film as the pocketknife-wielding Jodie) do a seamless job of concocting a more elaborate network of schemes and double-crosses for the film version, embellishing the novel’s plotline to accommodate additional opportunities for action, and (happily) granting Imabelle more agency and prominence in her own story.

PERFORMANCES

At the risk of seeming to give short shrift to the uniformly superb performances given by each and every member of A Rage in Harlem’s distinguished, absolutely flawless ensemble cast, my mania for tough women in tight clothes requires I rave a bit about Robin Givens. In this, her film debut, Robin Givens is both a force of nature and a force to be reckoned with. Giving an assured and witty performance that really should have made her a bigger star, Givens makes the most out of every moment she’s onscreen, imbuing her Imabelle (a non-tragic Carmen Jones by way of Lena Horne’s Georgia Brown from Cabin in the Sky) with all the danger and radiance of a bonafide film noir siren.

|

| The City Slicker is the Rube / The Country Bumpkin is the Smoothie If Robin Givens is the main reason why I watch A Rage in Harlem, Forest Whitaker is the main reason A Rage in Harlem works at all. |

One of the subtly amusing things about Imabelle is her self-possessed, exaggerated sexiness. I say self-possessed because while she is keenly aware of the effect she has on men, she’s mostly aware that she has that effect on EVERYBODY. She dresses in clothes so tight and confining, they should inhibit her, but she looks so comfortable and relaxed in them, they become a kind of snakeskin armor. Like in that old episode of Rocky and Bullwinkle in which Pottsylvanian villainess Natasha Fatale complains of discomfort and aching feet after briefly having to endure loose clothing and comfortable shoes, Imabelle and her impossibly tight clothes are one and the same. You can’t imagine her wearing anything else.

|

| The versatile Gregory Hines gives a winning comic performance that flows effortlessly into affecting drama |

As their roles function in the narrative, Robin Givens is the heat and Forest Whitaker is the heart. His Jackson is almost childishly naive, but Whitaker never plays him as dumb. Jackson's Baby Huey innocence contrasts appealingly with Imabelle's worldliness in a way that recalls the pairing of Stanwyck and Cooper in Ball of Fire (1941). Whitaker's scenes with Givens are dynamic and disarmingly moving. Whitaker somehow is able to convey the depth of Jackson's devotion to Imabelle. It's as though when he looks at her, he's not simply thunderstruck (as we are) by her physical beauty, he sees the dormant goodness in her heart.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

In a world that uses the spectacle of Black suffering—via news, social media, and motion pictures—for the dual purpose of tacitly reinforcing a toxic power myth while simultaneously providing Anglo viewers with the most accessible, least authentic means of countering the broader culture of Black dehumanization (pity requires less effort than respect); the depiction of Black death in action and crime films presents a unique dilemma.

American film history gives us an onslaught of images of Black pain that have yet to be offset and counterbalanced by an equal representation of Black joy and triumph (or survival, for that matter). Every violent death of a Black character onscreen, whether it's the filmmaker's intent or not, carries with it a historical, socio-political weight that extends far beyond the film’s aspect ratio.

All racism is violence, and the world Chester Himes depicts in A Rage in Harlem is reflective of and responsive to the harsh, Jim Crow world he inhabited. A world, not all that different from today, where police brutality was the norm and authorities didn’t even consider the killing of a Black man to be murder. When the film version of A Rage in Harlem was released, it received criticism for what was perceived by some to be the softening of the raw intensity of the violence in Himes’ book.

Perhaps this is true (plenty brutal enough for my tastes, the film extracts tension more from the ever-present threat of violence than showing us the real thing), but to take issue with it is to ignore something I’m glad Duke and his artistic collaborators appear to understand very well: that images of Black brutality are far more familiar to Black movie audiences than images of Black romance, humanity, and lovingly-recreated nostalgia for a place that was a home and cultural mecca of art, music, and literature.

Descriptive passages devoted to the destruction of Black lives are powerful enough in a book, but it feels like it would be irresponsible (or require an uncommonly deft hand) to have those violent actions depicted faithfully in the hyperrealist medium of film. Especially in a movie that is essentially comedic in tone.

I love film noir, but classic examples of the genre only offered invisibility for people who looked like me…that, or the opportunity to portray maids, porters, and piano players.

Black life is at the forefront of A Rage in Harlem, with all its absurdity, danger, and spiritedness. It features just enough violence and action to justify its qualification as a crime thriller, but it likes its characters too much to make their suffering just another exhibit added to the ongoing spectacle of Black suffering and death by which so many would have us defined.

Robin Givens and Forest Whitaker in a clip from "A Rage in Harlem" (1991)

Rage: An intense feeling of anger.

To seethe with desire or appetite.

To blow off steam.

A Rage in Harlem

The credit sequence illustrations are attributed to Joe Bachelor.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2019