Before I saw The

Sterile Cuckoo in 1969, I had only the vaguest impression of Liza Minnelli. I had a dim memory of her as this somewhat hyperactive, inauthentic personality who popped up occasionally on

her mother’s variety TV show, and another as an over-earnest Red Riding Hood in a 1965 musical TV

special titled The Dangerous Christmas of Little Red Riding Hood. Having missed her film debut in the 1967 Albert Finney vehicle Charlie Bubbles, The Sterile Cuckoo marked my first encounter with Liza Minnelli, the

actress, and, in the character of Pookie Adams, my first exposure to what eventually evolved into Liza

Minnelli, the screen persona.

|

| Liza Minnelli as Mary Ann "Pookie" Adams |

|

| Wendell Burton as Jerry Payne |

Pookie, an outcast who aggressively overcompensates and guards her lonely vulnerability behind the labeling of others as “creeps,” “weirdos,” or “bad eggs,” is clearly drawn to the nice, button-down sweetness of the biology major, but one senses that she's a type that habitually latches onto strangers. For his part, the overwhelmed Jerry doesn't so much warm to Pookie’s charms as succumbs to the force of her persistent will.

|

| Pookie worms her way into yet another heart |

As a 12-year-old kid enamored of too-mature films I scarcely understood, The Sterile Cuckoo was one of the few movies I saw during this period that didn't feel like a two-hour excursion into the uncharted territory of mysterious adulthood. Although the characters are supposed to be 18 or 19, the issues plaguing Pookie and Jerry (friendships, identity, loneliness, peer group acceptance) were, for the most part, things to which I could both relate and recognize within myself. I identified with Jerry’s timidity and deliberate, watchful approach to others. Likewise, as a gay youth, I empathized both with Pookie’s perception of herself as an outsider and her reject-them-before-they-reject-you, knee-jerk defense mechanisms.

But what I think I responded to most was the film’s insight into the dynamics of a relationship between two loner personalities drawn together in their isolation. Both Pookie and Jerry are insecure, but each responds to their circumstances differently. Pookie’s insecurity causes her to alienate all others except the one person she selects to smother with all the love she has, all the while emotionally draining them with demands for all the love she needs. Jerry lacks confidence as well, but as his insecurity is neither fear-based nor self-defensive, he's capable of recognizing that most everyone is a little afraid to reach out to others, and that what matters is that one make a little effort.

Unlike the offensive message behind the beloved 1978 musical Grease, whose moral is to encourage teenage girls to change everything about themselves in order to gain peer acceptance, The Sterile Cuckoo is not a film about the need to conform... it's about the inevitability of growing up.

|

| "Pookie, maybe they aren't all so bad. Maybe everybody's just a little cautious of everybody." |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

Always a sucker for movies about vulnerable characters (and

movies that make me cry), I fell in love with The Sterile Cuckoo and saw it about six times back in 1969. It sold

me on Liza Minnelli as a genuinely talented actress, and inspired me to read the

surprisingly different-in-tone John Nichols novel. For the longest time I harbored a memory of The Sterile Cuckoo as just a sad/funny look at first love, and perhaps that’s all it's intended to be. But seeing

the film today, in light of all we've come to learn about mental illness (coupled

with our culture’s obsession with medicating all idiosyncrasies out of the

human personality); I’m struck by how seriously disturbed Pookie seems to me now. That certainly wasn't the case when I was young. She starts out as some kind of early exemplar of the Manic Pixie Girl cliché, but

what with her self-delusions, pathological lying, death-obsession, mood swings, and

crippling persecution complex, it’s hard to shake the feeling that Pookie is considerably more than just a wounded misfit in search of someone to love her.

|

| Death-fixated Pookie likes to hang out in cemeteries |

Liza Minnelli deservedly won an Oscar nomination for her intense and deeply

committed performance in The Sterile

Cuckoo. Cynics and the industry savvy might take issue and label such an

ostentatiously underdog role as Pookie Adams--significantly altered and made more sympathetic (pathetic?) than in the novel--to be just the sort of calculated Oscar-bait to

attract Academy attention. But given that a similar gambit didn't work for Shirley

MacLaine that same year for what many consider to be an equally manipulative and maudlin turn in Sweet Charity; I think it’s fair to say

that Minnelli put this one over in spite of Pakula’s and screenwriter Alvin

Sargent’s (Paper Moon, Ordinary People) determination to stack

the emotional deck so heavily in her favor.

|

| The character of Pookie Adams was conceived for the screen as one far more tragic than depicted in the novel. |

It’s popular to dismiss the less-showy work of newcomer Wendell Burton in the reactive, relatively thankless role of Jerry Payne, but I think his low-key naturalism and likability provide the perfect contrast to the nervous hyperactivity of Minnelli’s character (it’s impossible to watch her Pookie Adams and not think of Anne Hathaway's legendary eagerness to please). His character’s subtle growth is very well played, and to Burton’s credit, he’s never wiped off the screen by Minnelli (no easy feat, that). At the time of The Sterile Cuckoo's release, Burton appeared poised for stardom. But after next appearing in an almost identical role as a soft-spoken prison inmate in Fortune & Men’s Eyes (1971) he worked primarily in TV before retiring from acting in the late 1980s.

|

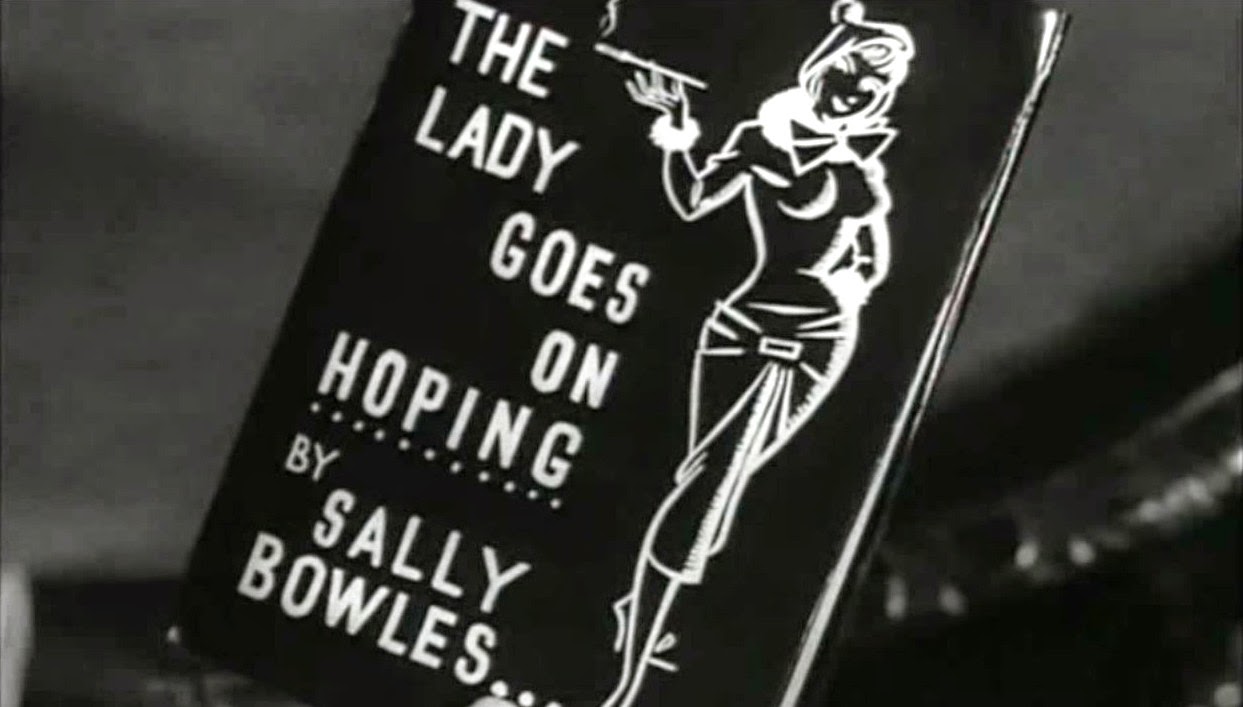

Earlier I mentioned how The Sterile Cuckoo marked my introduction to Liza Minnelli, the screen persona. By this I mean that for all intents and purposes, one can find the genesis of the entirety of Liza Minnelli's adapted screen persona in The Sterile Cuckoo’s Pookie Adams. Nowhere is this more obvious than in its similarities to her Oscar-winning role in Bob Fosse's Cabaret (1971). Fans of that film are apt to recognize in Pookie Adams a nascent version of Sally Bowles.

Pookie & Sally: A Comparison

Pookie & Sally: A Comparison

1. Both sport waifish, gamine bobs.

2. Both mask their inherent insecurity behind displays of delusional self-confidence.

2. Both mask their inherent insecurity behind displays of delusional self-confidence.

3. Both win over reluctant, passive men through the sheer force of their personalities.

4. Both suffer from neglectful fathers.

5. Each has a big emotional breakdown scene that virtually screams, “Give that girl an Oscar!”

6. Both have pregnancy scares.

5. Each has a big emotional breakdown scene that virtually screams, “Give that girl an Oscar!”

6. Both have pregnancy scares.

7. Both have gaydar issues. Pookie thinks (perhaps correctly) that Jerry’s roommate

is gay, while Sally fails to detect that her boyfriend and her lover are bisexual.

8. Both wind up scaring off their lovers.

8. Both wind up scaring off their lovers.

|

| Come-on: Would you like to peel a tomato? |

|

| Come-on: "Doesn't my body drive you wild with desire?" |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

The Sterile Cuckoo is

one of those forgotten movies in need of rediscovery. It’s more character-based than story-driven, so it's not heavy on plot; Pookie’s character can prove more annoying than poignant to some; and if you

take a dislike to the film’s Oscar-nominated theme song “Come Saturday Morning,”

you’re likely to be sent screaming into the streets, for it comprises the

totality of the film’s soundtrack. But to me, it’s a perfectly wonderful film of humor, sensitivity, and considerable emotional insight. Beautifully shot and an authentic-feeling record of the late '60s, The Sterile Cuckoo has standout performances throughout (Minnelli is at times phenomenal in this), and I think the conveyance of the brief romance is beautifully handled...both its beginning and its painful end. Definitely worth a look.

Oh, and as to the significance of the title? Nowhere to be found in the film (allegedly cut), but referenced in the novel as a poem Pookie writes about herself.

Mark, at Random Ramblings, Thoughts & Fiction and a few Internet friends have all shared with me tales of having had encounters with a real-life Pookie Adams, so I figured I should share my own.

My particular Pookie was a bit of an outcast, wore glasses, and was ragingly funny. She was keenly perceptive and cutting when it came to the shortcomings of others, yet oblivious to her own. She was a deeply loyal friend, but somewhat suffocating in that if you were her friend, you had to be only HER friend. There was no room for anybody else. She was happiest in having the two of us share all of our time together sitting apart from others and putting them down. In my own insecurity, this felt for a time like a kind of strength to me, too, but it wasn't long before I recognized what a self-defeating, one-way street this attitude was.

Oh, and as to the significance of the title? Nowhere to be found in the film (allegedly cut), but referenced in the novel as a poem Pookie writes about herself.

Mark, at Random Ramblings, Thoughts & Fiction and a few Internet friends have all shared with me tales of having had encounters with a real-life Pookie Adams, so I figured I should share my own.

My particular Pookie was a bit of an outcast, wore glasses, and was ragingly funny. She was keenly perceptive and cutting when it came to the shortcomings of others, yet oblivious to her own. She was a deeply loyal friend, but somewhat suffocating in that if you were her friend, you had to be only HER friend. There was no room for anybody else. She was happiest in having the two of us share all of our time together sitting apart from others and putting them down. In my own insecurity, this felt for a time like a kind of strength to me, too, but it wasn't long before I recognized what a self-defeating, one-way street this attitude was.

We were an insulated, impregnable world of two, but it was a world of cowards. As much as I enjoyed her company, the ultimately toxic nature of her mean-spirited humor (it was so obvious that she was in pain and so afraid of others) drove us apart. I see in The Sterile Cuckoo and Liza Minnelli's excellent performance an exacting depiction of a certain kind of wounded personality. One I'm learning is not as unique as I'd once thought.

Scene from "The Sterile Cuckoo" 1969

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)