I've a limited exposure to the British New Wave—that

post-war cultural movement in theater, literature, and film which propelled the lives

and concerns of working-class England to the forefront and ushered in the '60s vogue

for socially conscious kitchen-sink dramas like Look Back in Anger (1956) and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960)—but of the few films I have seen, most have been distinguished by their decidedly testosterone-laden, male-centric perspective. So much so

that in a great many cases, the “Angry Young Man” genre description could just as well serve as a plot synopsis.

In these films, the leading men are depicted as a rebellious, restless bunch, ofttimes violently chafing at the constraints of the British class

system. Meanwhile, the women are largely portrayed as either fun-killing domestic

drudges standing as ball-and-chain obstacles to the hero’s independence, or

sexually available conquests whose troublesome biology (they do get pregnant

at the most inconvenient times!) brands them potentially dangerous anchors to a life of lower-class

squalor.

|

| The "Honeyglow" Girl The ideal of the modern woman |

Not to discount Look Back in Anger in its entirety, but I loathed the passive roles played by Mary Ure and Claire Bloom. Ure’s submissive

doormat reminded me of nothing more than Wilma Flintstone as the browbeaten

housewife in the teleplay, The Frogmouth.

By contrast, I very much liked Simone Signoret’s worldly older woman in Room at the Top (1959) and Rachel

Roberts’ complex widow in This Sporting

Life (1963). But for all of their depth and dimensionality, neither character (tellingly, perhaps) came to

a particularly good end. It ultimately took doe-eyed Rita Tushingham in Tony Richardson’s

marvelous A Taste of Honey (1961) to provide a welcome change-of-pace from all this masculine disagreeableness shrouded

in societal disillusionment. In my narrow experience, Tushingham’s spirited

Manchester teen remained the lone feminine voice of the Brit-based genre until one day when I happened upon

John Schlesinger’s Billy Liar (1963)

and that force of nature known as Julie Christie.

Julie Christie’s entire role in Billy Liar can’t amount to

more than ten minutes of screen time, but as the easygoing, independent-minded

Liz (a girl so unlike the other clingy, provincial, ready-to-wed women in the film as

to be another species of being), Christie emerged the only one I even remembered. The frank simplicity of her performance, coupled with her refreshingly

open, guileless glamour, proved to be something of a bellwether moment in the

British New Wave. A turning point of sorts, in the evolution of women in British

cinema. Come the mid-'60s, the reversal of England’s post-war economic decline signaled a gradual

abandonment of these sparse and spartan tales of social oppression. Instead, Northern England’s

working-class suburbs were replaced by the burgeoning mod scene of swinging London, and the by-now familiar class rebellion commentary gave way to observant social satires taking pot shots at provincialism, consumerism, and the emergent dominance of youth culture.

|

| Julie Christie as Diana Scott |

|

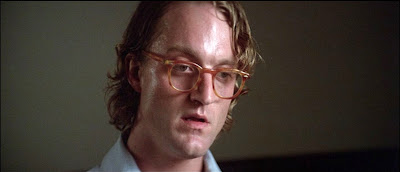

| Dirk Bogarde as Robert Gold |

|

| Laurence Harvey as Miles Brand |

|

| Roland Curram as Malcolm |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

Perhaps because of all the macho bullying behind so much of it, I’ve

never much warmed to the whole “Angry Young Man” genre. Angry Young Woman…now

that’s another matter. Only two films come to mind: the above-mentioned A Taste of Honey; and the

rarely-mentioned 1985 Meryl Streep drama, Plenty.

A film that, while not technically an

example of the genre, is a wonderful female-centric perspective of post-war

British disappointment.

There is no obvious Angry Young Woman in Darling, but there is something akin to rage at the center of what

is eating at the never-satisfied-for-a-moment Diana. You see it in today’s

films. Those romantic comedies where women are characterized by how much they

shop and the label of the clothes on their backs. The films where the women are

near perfect physical and intellectual specimens, yet their very "femaleness”

is a weakness that dooms them to relationships with doofus schlubs like Seth

Rogen. Those awful Sex and the City

films where the over-privileged girlfriends can’t stop complaining or bemoaning their first-world problems for a minute and just count their blessings…it’s the same thing (Indeed, Diana Scott would

fit right in with Carrie Bradshaw and her “I want it all, but I'm pretty sure I won't be fulfilled when I get it” tribeswomen).

|

| Sexual liberation yields little more than serial dissatisfaction |

I don’t know about you, but when I see compulsive consumerism of the

sort engaged in by women in today’s films as some sort of empowering

birthright, I can’t help but feel there are some real hostilities and angers

being repressed and swallowed up in this obsession with fashion. I can’t believe

the battlefield of women’s liberation has become the local outlet store.

What I like about Darling is

how relentlessly it lampoons this culture we have fashioned for ourselves that

sells people ideas of "lifestyles" rather than encourages us to find an actual life. Like a

similar character played by Jacqueline Bisset in the 1970 film The Grasshopper, Christie’s Diana Scott

has been led to believe that “liberation” is a complete lack of ties to

anything. Even herself. As she flits from one dissatisfying situation to

another, it never dawns on her that she has been sold a prepackaged,

consumerist bill of goods as to what real freedom and happiness is. The chic

trappings of the swinging lifestyle promoted by mod London are chiefly

beneficial to the shopkeepers, stores, and businesses. For Diana, climbing the

ladder of upward mobility ultimately offers her nothing more than increasingly

sumptuous surroundings to feel desperately lonely in.

|

| Having it All |

PERFORMANCES

I’m mad about everything in this film, but Darling is far from being the favorite film of many. Some find it

dated, others complain of the satire being too heavy-handed; even the late John

Schlesinger stated in later years “(Darling)

seemed altogether too pleased with itself” and claimed his film was guilty of

“epigrammatic dialog” that came off as self-consciously hip. Where all opinions converge and most everyone is in agreement (even Schlesinger) is on the topic of Julie Christie's star-making performance. So natural a presence that the film takes on the feel of documentary whenever

she’s onscreen. You can't take your eyes off of her.

|

| I've always wondered if the career of popular '60s British actress Judy Geeson (To Sir, With Love, Bersek) was either plagued or assisted by her more-than-passing resemblance to Julie Christie |

An entire generation fell in love with Christie because of this film

and it’s not hard to see why. In this her Oscar-winning role, Christie exhibits

that appealingly straightforward quality that would characterize her entire

career. She displays an incredible range and finds the humanity and humor in a

character not exactly likable. It’s always interesting when a smart actor

plays a not-very-bright character. Christie doesn’t condescend in her portrayal

of the shallow Diana. She conveys the character’s intellect in terms of a keen,

almost animal awareness of knowing which way the wind is blowing and shifting

her sights accordingly. Julie Christie is just a marvel here and endlessly

resourceful in getting us to know more about a character who knows absolutely nothing

about herself.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

In films with lead actresses as talented and drop-dead gorgeous as

Julie Christie, it's not uncommon for the male characters to fade into the

background. Not so with Darling. In

fact, I can’t think of a film with a more solid, impressive, and eye-pleasing

male cast. As a nice change of pace, the men in the cast are, by and large, more

sensitive and emotionally needy than the heroine. Few actors have combined

suave masculinity with vulnerable sensitivity as persuasively as Dirk Bogarde.

As television reporter Robert Gold, Bogarde’s grounded sincerity (so easily

read in his expressive eyes) casts a by-contrast harsh light on the frivolous

affections of Christie’s Diana.

|

| Diana (Christie) allows her vulnerabilities to show with her friend Malcolm (Roland Curram) |

Of course, the terrific Laurence Harvey (a delight in 1959s Expresso Bongo) makes for a rakishly

reptilian—and surprisingly sexy—competitor for Diana’s affections, but Roland Curram in the role of Diana’s photographer

friend, Malcolm, really made me sit up and take notice when I first saw Darling. For not only is the

character of Malcolm funny, handsome, and a good friend, but Malcolm is that rare

of rarities: a likable, non-tragic, non-campy, unapologetically sexual, gay

character. In a film made in 1965, no less! As the only genuinely decent

character in the film, his scenes with Christie are refreshingly convivial and

the only times her character ever appears to relax into herself.

|

| Diana and her Gays Darling was one of the earliest films to depict gay characters in a sympathetic light |

Strangely, for a film with

such a progressive attitude towards homosexuality, it seems the

closets were full-to-bursting behind the scenes. Matinee idol Dirk Bogarde was

deeply closeted yet engaged in a brief fling with openly gay director John

Schlesinger during the making of Darling

(according to authorized Schlesinger biographer William J. Mann). Bogarde

enjoyed a 40-year relationship with his agent, Tony Forwood, but invested

considerable energy (throughout several autobiographies) in portraying himself

publicly as a heterosexual. John Schlesinger harbored hopes that his friend, Roland Curram, might be inspired enough by his role in Darling to come out of the

closet. Amused by his friend's presumption, Curram always insisted on his heterosexuality and went on to marry and

later sire two children. In 1985, on the occasion of his divorce and ultimate coming out

to his family and himself, Curram stated, “Of course, I told John later that he

was right.”

|

| Unfaithfully Yours - Diana's twin deceptions Robert: "Your idea of fidelity is not having more than one man in bed at the same time" |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

I first saw Darling in 1980,

by which time you’d think the film’s satirical slant would have lost its edge. That

at least would be expected. The scary (and sad) thing is that while the jabs have

lost their bite due to over-saturation, the chosen targets are nevertheless every

bit as wanting of lampooning today as they were in 1965. I find it uncanny that the social absurdities Darling poked fun at 52- years ago (TV commercials, fame whores, liberal

hypocrites, self-righteous homophobes, promiscuity for profit, the myth of “having

it all”, etc.) are still a prominent part of our pop-culture landscape.

Darling is the film that made stars of both Julie Christie and John Schlesinger. Schlesinger's next film would be his last with Christie; the big-budget adaptation of the Thomas Hardy novel, Far From the Madding Crowd (1967). After which he would go on to make the classics: Midnight Cowboy, Sunday, Bloody Sunday, and The Day of the Locust. Schlesinger passed away in 2003.

Julie Christie is a legend, of course, and the promise of Darling has been realized in film after film throughout her career. Few actresses get to become iconic stars; fewer still owe it all to introducing to the cinema a new image of womanhood. There are many remarkable actresses around, but there is only one Julie Christie...she is in a class by herself.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2012

.JPG)

.JPG)