“After Michael

Redgrave played the insane ventriloquist in Dead of Night, bits of the

character’s paranoia kept turning up in his other performances; it would be

hair-raising if Faye Dunaway were to have trouble shaking off the gorgon Joan.”

Pauline Kael - The New Yorker Oct.1981

This is one reason why, when I first read Mommie Dearest—Christina Crawford’s bestselling memoir detailing the physical abuse she suffered at the hands of her adoptive mother, screen legend Joan Crawford—I was among those who had no problem believing the allegations made against Crawford to be true. For those of us who grew up in the "spare the rod, spoil the child” era, the behavior described in Mommie Dearest was considerably less shocking than who was engaging in it: Mildred Pierce herself, Joan Crawford.

However the memoir was received, the one thing everybody agreed upon was that Mommie Dearest had wreaked irreparable damage to Joan Crawford’s hard-fought-for image. Virtually overnight the name of Joan Crawford had become an instant punch line (no pun intended, but see how easy that was?).

The audience that crowded the Chinese Theater that opening

day in 1981 was abuzz with that rare kind of anticipation born of knowing you were

about to see a film that promised a rollicking good time whether it was a

triumph or a travesty. A win-win situation!

For about five minutes, Mommie Dearest really looks

like it’s going to work...and then the audience gets its first look at Faye

Dunaway in her Joan Crawford makeup. Although the transformation is impressive,

the effect is startling in all the wrong ways. Gasps are followed by giggles,

giggles erupt into guffaws, and Mommie Dearest never really regains its

footing.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

PERFORMANCES

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

BONUS MATERIAL

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2011

Pauline Kael - The New Yorker Oct.1981

I grew up during a time when it was common practice to apply

hairbrushes, belts, or sturdy switches (a thin branch from a tree or a stalk

from a root or plant) to the backsides of children in the interest of instilling "discipline." Back then, kids knew the likely consequence of disobedience or backtalk was to get “a

whipping” (spanked), or, if in public, a pluck to the ears or smack to the back

of the head (seriously!). Misdeeds failing to warrant physical punishment were

met with verbal reprimands ("Shut up back there!”), threats (“Mouth off to me again and I’ll

slap you clear into next week!”), or other colorful forms of what we now know to be verbal/psychological abuse (“What are you, stupid?”).

Welcome to Parenting 101: The Pre Dr. Spock years. Whether

it be corporal punishment, verbal abuse, or psychological intimidation (“Wait

‘til your father gets home!”); our parents did it to us because their parents

did it to them. No one bothered to question such behavior for the administering of strict parental discipline was widely

held at the time to be the single ingredient marking the difference between the raising

of a worthless juvenile delinquent, or a contributing member of society.

|

| This hurts me more than it does you |

This is one reason why, when I first read Mommie Dearest—Christina Crawford’s bestselling memoir detailing the physical abuse she suffered at the hands of her adoptive mother, screen legend Joan Crawford—I was among those who had no problem believing the allegations made against Crawford to be true. For those of us who grew up in the "spare the rod, spoil the child” era, the behavior described in Mommie Dearest was considerably less shocking than who was engaging in it: Mildred Pierce herself, Joan Crawford.

If ever there was an individual who epitomized the words

“movie star,” it was Joan Crawford. Everything about her finely burnished image

fed the public perception of her as a hardworking, glamorous star of ladylike hauteur

and refinement. While other stars were battling studio heads, suffering public

meltdowns (would Mommie Dearest have caused such a sensation had its

subject been one of Hollywood’s more famously unstable stars like Judy Garland?),

and living flashy lives of decadent excess, Joan always conducted herself as though she were Hollywood’s unofficial Goodwill Ambassador.

Published in 1978 (only one year after Crawford’s death), Mommie Dearest caused quite a sensation.

Not only was it one of the earliest examples of the tell-all celebrity memoir, but it was one of the first popular books to shed light on the problem of child abuse.

These days, I would welcome any public figure who didn’t feel compelled to publicly air their abuses, addictions, and mental-illnesses; but

in 1978, it was a rare thing indeed to publish such an incendiary airing of dirty-laundry

about a movie star. Especially one with an image as scrupulously manicured as that

of Joan Crawford.

I saw the film Mommie

Dearest the day it opened at Hollywood

To this latter group, the events of Mommie Dearest somehow bypassed sympathetic analysis and barreled

headlong into being a book enjoyed as a Jacqueline Susann- esque hybrid of old

Joan Crawford movies (specifically Queen Bee, Harriet Craig, and Mildred Pierce) crossed with The Bad Seed. I don’t know whether it

was Crawford’s grand diva posturing or society’s deep-seated resentment of the

rich and famous, but there was just something about Mommie Dearest that many readers found irresistibly satirical.

|

| Pathos Undermined Being screamed at by your mother: Traumatic Being screamed at by your mother who's decked out in a sleep mask, chin strap, and night gloves: Priceless |

However the memoir was received, the one thing everybody agreed upon was that Mommie Dearest had wreaked irreparable damage to Joan Crawford’s hard-fought-for image. Virtually overnight the name of Joan Crawford had become an instant punch line (no pun intended, but see how easy that was?).

|

| Faye Dunaway IS Joan Crawford |

|

| Diana Scarwid as Christina (adult) |

|

| Mara Hobel as Christina (child) |

|

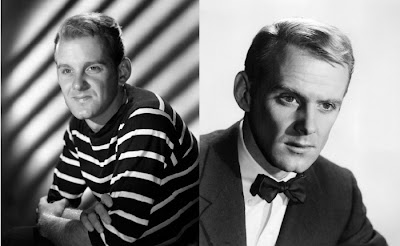

| Steve Forrest as Greg Savitt |

Much in the manner that the incredibly stylish cubist/art

deco title sequence for Lucille Ball’s Mame (1974) proffered hopes (quickly

dashed) of a classy entertainment that never materialized, Mommie Dearest

got off to a very promising start with a dramatically evocative, cinematically

economical montage detailing the pre-dawn preparations going into the

creation of Joan Crawford, the movie star.

It’s a marvelous sequence of compulsive self-discipline and

dues-paying professionalism that turns a morning bath into a near-religious purging ritual

built upon the duty and sacrifice of stardom. (I particularly like how

Crawford, autographing photos in the back seat of her limo as she’s driven to

the studio, never allows for a moment of idleness. It calls to mind my

perception of what Oprah Winfrey must be like in her private moments…I

seriously don’t know when that woman finds time to sleep.)

|

| Joan Crawford, world-class multi-tasker |

Which is really too bad, because Dunaway, who works her ass

off, is really rather good (at least in that dicey, Al Pacino in Scarface

/ Jack Nicholson in The Shining way: where a ridiculous performance can

be made to work under the right circumstances).

She deserved a better script, a surer production, and a director

protective enough to rein her in when she went over top. Which, alas, is

pretty often.

Perhaps it was misguided to even attempt to make a serious

motion picture about an actress whose extreme sense of glamour (padded

shoulders, mannish eyebrows, smeary lipstick, and mannered acting style) had long

ago made her a camp gay icon and favorite among drag queens, impressionists,

and parodists (Carol Burnett’s Mildred

Fierce comes to mind). But director Frank Perry (Diary of a Mad Housewife, Last Summer) and a battery of screenwriters only compounded

the risk by failing to find a dramatically viable means of adapting the material.

For starters, the film can't really decide whose story it is. Are we seeing Joan as Christina sees her (in which case Christina's psychological perspective gets incredibly short shrift), or is this a "behind the facade" look at a famous actress (which leaves us wondering, what's the point?).

America

For starters, the film can't really decide whose story it is. Are we seeing Joan as Christina sees her (in which case Christina's psychological perspective gets incredibly short shrift), or is this a "behind the facade" look at a famous actress (which leaves us wondering, what's the point?).

Mommie Dearest, like its titular subject, gets bogged

down with the superficial. Lacking in depth, the dialog, costuming, and

performances work in concert to turn each of its setpiece scenes into

high-style, $#*! My Mother Says.

|

| The illusion of perfection |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

I’m guilty of whatever human frailty it is which causes people

to rejoice when cracks are found in the façade of public figures who insist on

portraying themselves and their lives as perfect. I was one of those so shocked by Mommie Dearest’s unmasking of little-miss-perfect Joan Crawford as a

bit of a nutjob, that I failed to pay much attention to the not-so-funny issue

of child abuse, which should have been my focus from the start. Viewing Mommie Dearest today, so many years after its

release, I wonder if the film is not guilty of the same thing. The focus should

have been on the character of Christina, not Joan. It’s her story after all. Since

even the most world-famous parent is likely to be just plain old “mom” or “dad”

to a child, the resultant shift in focus might have offered a less traditional

view of Crawford and saved Mommie Dearest from becoming what it frequently feels like: the world’s longest drag

act.

|

| Joan Crawford's palatial Bel-Air home (top) first appeared as the mansion of gangster J. Sinister Hulk (Jesse White, bottom photo, left) in the 1964 Annette Funicello musical, Pajama Party |

PERFORMANCES

In spite of the many hours of enjoyment I've had at Faye Dunaway’s

expense (tears running down my cheeks, cramped stomach

muscles, desperate gasps for air between full-throated howls of joyous laughter),

as I've stated, I really think she does an amazing job in Mommie Dearest.

It’s not so much that she’s good, although she does have her moments; so much

as she’s incredibly brave and frighteningly committed. She throws herself into

the role so wholeheartedly that I don’t know that she can be completely faulted

for failing to land right on the mark.

I’m of the opinion that much of what is accepted as funny

about her portrayal of Joan Crawford is only partially her fault. No insult

intended to the Joan Crawford fans out there, but the real Joan Crawford in

full “Joan-mode” is pretty hilarious. Dunaway’s impersonation is so spot-on

that the laughs she gets can’t really be attributed completely to her performance/impersonation. I mean, those are Joan’s eyebrows and pinched-constipated smile; that is

Crawford’s butch, bitch-queen bossiness; and anyone who’s ever seen the level

of overwrought emotionalism she’s capable of bringing to even the most

easy-going scenes (check out Trog, sometime), knows that even a lot of Faye's overacting belongs to Crawford herself.

Dunaway makes some odd choices (the cross-eyed bit during the wire hangers scene is just

asking for it, and who exactly thought the whole “Don’t fuck with me, fellas!”

line was going to work?), but within the confines of a rather choppy script, there

is an attempt on Dunaway’s part to add some dimension to the at-times

cartoonish monster Mommie Dearest would have us believe is Joan Crawford.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Over the years I’ve come to the conclusion that Mommie

Dearest isn’t a bad film so much as a series of gross miscalculations all

around. Here are just a few things the makers of Mommie Dearest failed to take

into account:

a) 40s era Joan Crawford looks disconcertingly like Dr.

Frank-N-Furter in The Rocky Horror

Picture Show.

b) Power plays between curly haired brats and mannish glamour

stars are inherently funny.

c) Extreme wealth undercuts tragedy.

e) Casting a legendarily temperamental actress in the role of a legendarily

temperamental actress encourages the audience to wonder if they're watching Dunaway being Dunaway, or Dunaway being Crawford.

|

| Madonna & Child |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

There was a time

when I really couldn’t get sufficiently past Joan Crawford’s extreme look and

affected style of acting to see her as anything other than a comically camp

timepiece. Over the years I’ve come to appreciate her skill and talent, and

today she’s one of my favorite actresses. Mommie Dearest is

too flawed a film for even nostalgic revisionism to one day convert into a

misunderstood classic; but I think there stands a good chance that time will be

kinder to Faye Dunaway’s performance. Like many of the under-appreciated performances

of Marlon Brando that have come to light to be among his best (Reflections in a Golden Eye), Dunaway’s Joan Crawford may be a bit “out there” at times, but it

is a fascinating, almost athletic performance. Perhaps far more layered and intelligent than

the film deserves.

|

| Understatement of the Year Dept: "Today Faye sees herself 'as starting on a second phase of my professional life, just as Joan Crawford did...'" People Magazine Oct. 1981 |

Clip from "Mommie Dearest" (1981)

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2011