At a time when most of her industry peers were retired, forgotten, or guesting on episodes of Fantasy Island and The Love Boat, 56-year-old Lauren Bacall was enjoying a career resurgence and public visibility rivaling that of her 1940s heyday when she was known as “The Look.” The year 1981 saw Bacall headlining in the Broadway musical Woman of the Year; topping the bestseller charts with the paperback release of her 1978 memoir By Myself; shilling everything from jewelry to cat food in TV and print ads; and, most remarkably in those pre-Meryl Streep/Helen Mirren years of elder-actress marketability, starring in a nine-million-dollar major motion picture release.

The Fan, a suspense thriller based on Bob Randall’s 1977 epistolary novel about an aging Broadway star stalked by an obsessive fan, gave Bacall arguably the biggest role of her career. Certainly, the first to require her to carry an entire film on her own.

Filmed on location in New York from March to July of 1980, The Fan was poised for release at the most opportune time to take marketing advantage of Bacall’s already-in-motion Broadway and bookshelf publicity. Unfortunately, as The Fan’s PR-friendly release date of March 15, 1981 neared, several real-life, obsessive fan-based tragedies occurred (targeting John Lennon and then-President Ronald Reagan), conspiring to make this fame-culture melodrama seem more an exercise in bad taste than a film of ripped-from-today's-headlines relevance.

|

| Michael Biehn as Douglas Breen |

|

| Maureen Stapleton as Belle Goldman |

|

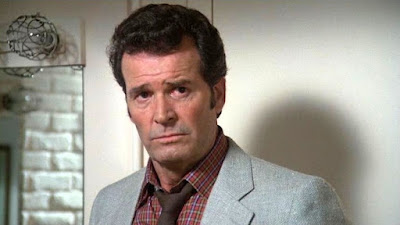

| James Garner as Jake Berman |

|

| Hector Elizondo as Inspector Raphael Andrews |

|

| Kurt Johnson as David Barnum |

If musical theater geeks, Glee habitués, and folks capable of making it through an entire Tony Awards broadcast ever longed for an '80s slasher film to call their own, then The Fan more than fills the Playbill. This unappetizingly bloody, yet oh-so delectable/derisible blend of backstage musical, 1940s career-woman soap opera, slasher-flick, and woman-in-peril melodrama, is high-camp movie nirvana. An upscale cousin of the hagsploitation genre of the '60s, The Fan might have substituted seasoned glamour for the usual grotesquery, but in keeping with the requirements of the sub-genre, The Fan's raison d'être remained the prolonged persecution and victimization of a mature star from Hollywood's Golden Era.

When The Fan opened in theaters in the spring of 1981, the film...to borrow a line from one of the hooty Louis St. Louis (Grease 2) showtunes sung in the film..."Got no love” from either audiences or critics. Patrons old enough to be enticed by the film's elder cast risked having their blue rinses turn stark white at the sight of the movie's copious bloodshed and some of the blunt, Bogie-wouldn't-stand-for-this dialog: “Dearest bitch, see how accessible you are? How would you like to be fucked by a meat cleaver?” Similarly, the teen demographic ordinarily drawn to slasher films weren't quite sure of what to make of a movie set in the middle-aged, Sardi's and cigarettes world of New York legitimate theater. A wholly uninspired publicity campaign only added to the film’s troubles

|

| The stark graphic design of the poster had a generic slasher film look that did nothing to sell the film to the public. |

Had The Fan been a play, it would probably have closed in Boston. Whisked off screens within weeks of its release, The Fan resurfaced with some regularity on cable TV venues like HBO and Showtime throughout the '80s before ultimately disappearing into relative obscurity. Obscurity so complete that Robert De Niro's unrelated but same-titled 1996 sports-themed film has totally eclipsed Bacall's The Fan in the public's memory.

Happily, The Fan's recent release on DVD has rekindled awareness of this very '80s curio. A glimpse back at a New York still atmospherically seedy. A vision of a world populated with record stores, typewriters, payphones, legwarmers, and heavy smokers. All with nary a Starbucks in sight. And while it's no undiscovered classic, The Fan does have its merits (most of them camp-related, I'm afraid) that make it a movie worthy of rediscovery. Not the least of them being Lauren Bacall, a smoking, drinking, tough-as-nails star of Broadway and the silver screen, playing a smoking, drinking, tough-as-nails star of Broadway and the silver screen. And convincingly, too!

The intersect of stardom and fandom

No low-budget, body-count slasher flick featuring nondescript teens stalked by a masked phantom, The Fan was conceived as a stylish, A-List, Hitchcockian thriller along the lines of Eyes of Laura Mars (1978) and Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill (1980). The latter, a sleeper hit that garnered '50s sexpot, Angie Dickinson, some of the best notices of her career.

At least that's how things started.

At least that's how things started.

Produced by movie/music mogul Robert Stigwood on the downturn side of a '70s winning streak that included youth-centric films like Jesus Christ Superstar, Saturday Night Fever, and Tommy; The Fan was Stigwood’s most expensive film to date and first stab at cracking the grown-up ticket-buying market. To this end, he amassed a distinguished cast of New York actors and pedigreed Broadway composers (Marvin Hamlisch and Tim Rice collaborated on two–fairly terrible but nonetheless irresistible–original songs). On the production end, he secured the talents of up-and-coming first-time director Edward Bianchi (from TV commercials and music videos) and choreographer Arlene Philips (Can’t Stop The Music, Annie).

If you've ever seen a Lauren Bacall musical, you know that her being lifted and carried about is a choreography requisite. I was surprised at the number of online reviews that questioned Bacall's "believability" portraying a Broadway musical star in The Fan. Reviews that later expressed surprise upon learning that she was indeed a musical theater star in real life. Bacall was the Best Actress Tony Award winner for both Applause - 1970 and Woman of the Year - 1981.

But as the saying goes, the best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry, and somewhere between screenplay to movie-house, The Fan transmogrified into a film beset by:

1) Bad decisions - Friday the 13 became a hit during The Fan's post-production, prompting Paramount to order reshoots to ratchet up the violence.

2) Bad timing and bad decisions - Three months before The Fan's release, John Lennon was killed by an obsessive fan outside NY’s Dakota apartments (as it happens, also the home of Lauren Bacall), after which it is said the film's original downbeat ending (if true to the novel) underwent some 11th-hour tinkering and reshoots.

3) Bad luck - Bacall's idea of promoting The Fan was to express to the press her disappointment in the finished product. Making matters worse, three weeks into The Fan's less-than-illustrious release, an attempt was made on President Reagan's life by a Jodie Foster-obsessed fan. Suddenly, a film very few people were interested in in the first place began to look to everyone like an exercise in exploitation and bad taste.

1) Bad decisions - Friday the 13 became a hit during The Fan's post-production, prompting Paramount to order reshoots to ratchet up the violence.

2) Bad timing and bad decisions - Three months before The Fan's release, John Lennon was killed by an obsessive fan outside NY’s Dakota apartments (as it happens, also the home of Lauren Bacall), after which it is said the film's original downbeat ending (if true to the novel) underwent some 11th-hour tinkering and reshoots.

3) Bad luck - Bacall's idea of promoting The Fan was to express to the press her disappointment in the finished product. Making matters worse, three weeks into The Fan's less-than-illustrious release, an attempt was made on President Reagan's life by a Jodie Foster-obsessed fan. Suddenly, a film very few people were interested in in the first place began to look to everyone like an exercise in exploitation and bad taste.

|

| Bacall the Buzzkill Bacall: "The Fan is much more graphic and violent than when I read the script." Anna Maria Horsford (who appeared in Stigwood's Times Square in 1980) as detective Emily Stolz |

Stigwood severely scaled back his usual bombastic pre-release publicity for The Fan (STD results have been released with more fanfare), while Paramount added a disclaimer to its theatrical trailers claiming The Fan was in no way inspired by the tragic death of John Lennon. The latter decision prompting the outspoken Bacall to declare to People magazine: “I think it’s disgusting, revolting, and exploitive!”

In the end, it didn't really matter, for The Fan wound up being one of those rare films capable of offering audiences simultaneously contradictory experiences–none of them satisfactory. Stylishly shot, overflowing in chichi urban gloss, and embellished with a chilling Pino Donaggio score (Carrie, Don’t Look Now) The Fan ultimately failed to find an audience because it clearly didn't know who the hell that was. Classic movie fans familiar with Lauren Bacall thought the film was too classy to be so trashy; slasher fans thought the film wasn't trashy enough. Gays had their own problems with the film.

|

| Strangers in the Night |

The Fan did itself no favors by alienating the very audience most receptive to a film offering up ample doses of musical theater, backstage drama, show tunes, tight male bodies in various states of undress, and Lauren Bacall in full Margo Channing mode. On the heels of Windows (1980), a stalker thriller about a lesbian psychopath, and Cruising (1980) a crime thriller about a gay psychopath; many members of the gay community felt The Fan's closeted theater-queen stalker was one gay psycho too many.

None of that applied to me, however. I was a presold audience in and of myself. I’d read The Fan back in 1978, intrigued by the way the book used the thriller genre to comment on the odd love/hate relationship between stars and their adoring public. I was also a longstanding fan of Lauren Bacall from her old movies with Bogart on The Late Show, Applause (the 1973 TV broadcast, anyway), and Murder on the Orient Express; so I was thrilled when I heard she'd been cast.

|

| Dana Delany making her film debut |

|

| Feiga Martinez as Elsa |

Adding to my anticipation was the fact that Edward Bianchi was hired to direct and Arlene Phillips was to do the choreography. Bianchi & Phillips had collaborated on a series of eye-popping Dr. Pepper commercials in the late '70s for the advertising agency Young & Rubicam. Commercials I had been inspired by and borrowed from for a couple of my film school projects. When I also learned that Broadway great Maureen Stapleton had joined the cast and that Bacall’s rumored real-life paramour, James Garner, was also on board, The Fan swiftly became one of the most eagerly-awaited films of the year...for me, anyway.

I saw The Fan on opening day at Grauman’s Chinese Theater where the smallish audience of young people in attendance (clearly in search of a good scare) was underwhelmed. I, on the other hand, felt as though I’d died and gone to camp film heaven. Not since Eyes of Laura Mars had I seen such a slick-looking thriller. One capable of being enjoyed on so many levels at once. I wound up seeing it a total of three times before it disappeared from theaters.

Shot on location, The Fan provides many great glimpses of 80s-era New York.Here the famed Shubert Theater is the site for Sally Ross' opening night in Never Say Never; the fictional musical providing The Fan with so much of its camp appeal

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

What brings me back to The Fan time and time again are its many sequences depicting the behind-the-scenes creation of the fictional Broadway musical Never Say Never, which is to be star Sally Ross’ singing and dancing debut. What with its use of recognized Broadway dancers, NY locations, and knowing attention to procedural detail; the feel is very authentic, very 80s, and very stylishly evoked. I find these scenes a bit camp to be sure (what with all those legwarmers and Arlene Philips' trademark Hot Gossip choreography), but I have to say all of it contributes to giving us a refreshingly novel backdrop for a suspense thriller. Silly as they may be, they are also terrifically fun. Of course, it doesn't hurt that I saw this film during my early days as a dancer, or that in 1983, when I took my first trip to New York, I studied dance at Jo Jo's, the studio featured in the film.

|

| That's Kurt Johnson providing literal backup to Lauren Bacall as she sings " A Remarkable Woman," one of two Marvin Hamlisch/Tim Rice compositions introduced in the film |

.JPG) |

| UK Choreographer Arlene Phillips wouldn't actually choreograph for Broadway until 1987's Starlight Express |

PERFORMANCES

If you’re going to make a film about the kind of old-school, glamorous, show-biz diva capable of inciting the flames of obsessive fandom, you couldn’t do much better than landing all-around class-act, Lauren Bacall. Her gravitas as a full-fledged movie star from the golden era gives The Fan a shot of instant legitimacy every time she appears. In one of the largest roles of her career, Bacall is not always filmed as flatteringly as you'd expect, but the effect is rather refreshing. Her face looks terrifically lived-in, and her still-striking looks serve as a welcome change from the botoxed mannequins we've grown used to. Playing a role that isn't perhaps much of a stretch, awfully good. So good in fact, that I kept wishing the film would just allow the story's natural character conflicts (an aging star grappling confronting loneliness, self-doubt, and vulnerability) play themselves out minus all the genre machinations.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

The '80s come vividly alive in the film's Broadway musical sequences, which are sort of Solid Gold meets Can't Stop The Music. As would be the case with the Broadway musical numbers in 1983s Staying Alive, it's near-impossible to imagine just what kind of Broadway this could be, as the numbers look more appropriate to a Las Vegas revue. But they left me wanting more, not less. (I feel safe in saying I'm likely the only person who felt that way.)

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

I've never considered The Fan to be as bad a film as its reputation has led people to believe. Its screenplay is clichéd to be sure (the stage doorman is actually named “Pop”) and the violence needlessly gruesome for such a visually distinguished and stylish film (Bianchi’s music video background is in full evidence), but with a provocative theme and talented cast, The Fan has quite a bit going for it even with its flaws.

|

| Griffin Dunne a few years before his breakout role in Martin Scorsese's After Hours (1985) |

Celebrity and fan obsession is a compellingly intriguing topic for a thriller. The whole codependent, love/hate, need/resent, fear/envy aspect of the “relationship” between the famous and the adoring public is ripe fodder for film treatment. The connection between celebrity and fan is a "relationship," by design and necessity, doomed forever to be one-sided: the fan feels an intimate kinship with someone who doesn't know they exist. Perhaps because of this imaginary, essentially hungry, connection, it's no surprise then how quickly fawning fandom can change to bilious hate if the fan’s attentions are even marginally rebuffed.

I’m reminded of a scene in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy (a marvelously dark black comedy about fan obsession that would make a great double-bill with The Fan) in which talk-show host Jerry Lewis is walking down the street. When asked by a fan at a public phone to say a few words to her friend on the line, he politely demurs, claiming that he's running late. At this point, the seconds-ago adoring fan flips to bile-spewing enemy, shouting “You should only get cancer! I hope you get cancer!” Yikes!

But such is the mercurial, frighteningly delicate line between love and hate that is fandom and celebrity obsession. Had The Fan set its sights on examining this already terrifying dynamic in the form of a strict psychological thriller, it had the potential for providing an insightful, genuinely chilling look at our increasingly celebrity-obsessed culture. In going the slasher/stalker route, The Fan cheapens and sensationalizes the material, making the events appear more remote and unlikely than in reality they are.  |

| "It's better than pot. It's better than booze. A shot of applause can stamp out the blues." Lyrics from the title song of Bacall's first Broadway musical "Applause" |

When it comes to The Fan, one might have wished for a little more finesse in the areas of motivation and character, but I seriously have a soft spot in my heart for this movie...mostly centered around the Broadway setting, the images of a still gritty and grimy New York, and reminders of my early years in dance. And, of course, it really is great to see late-career Bacall–with that amazing Gena Rowlands-like mane of hair–command the screen once more. Who was it that said, "Nostalgia ain't what it used to be"?

Clip of legwarmers in action in "The Fan" (1981)

.JPG)

.JPG)