Today to get the

public to attend a picture show,

It’s not enough to

advertise a famous star they know.

If you want to get the

crowds to come around...

You’ve got to have

Glorious Technicolor,

Breathtaking

CinemaScope,

And Stereophonic

Sound.

Cole Porter -1955 Broadway musical "Silk Stockings"

“The first big murder-mystery in CinemaScope!” “The first

crime-of-passion story in CinemaScope!" Thus screamed the poster and

newspaper ads heralding the 1954 release of 20th Century-Fox’s all-star, all-color, widescreen film noir, Black Widow. Well, seeing as I somehow managed to never even hear of this movie until just last year, I’m going to have to take them at their word that Black Widow represents a series of "firsts" in the annals of CinemaScope. What I can attest to is that by combining the backstage bitchery of All About Eve (1950) with the murder-mystery-told-in-flashback structure of Laura (1944), and burnishing it all to a garish, high-gloss color palette reminiscent of How to Marry a Millionaire (1953), Black Widow succeeds in being a pleasingly campy goulash of disparate genre tropes and style conventions in search of a unifying tone. |

| Ginger Rogers as overbearing diva of the New York stage Carlotta Marin |

|

| Van Heflin as slow-witted theatrical producer Peter Denver |

|

| Gene Tierney as patrician stage star Iris Denver |

|

| George Raft as the Beau Brummel of the NYPD, Detective Lt. C.A. Bruce |

|

| Peggy Ann Garner as Southern-fried "purpose girl" Nancy Ordway |

.JPG) |

| Reginald Gardiner as lapdog househusband Brian Mullen |

Set in the glamorous world of the New York theater (although

no one in the film ever sets foot on a stage), Black

Widow feels more like Americanized Agatha Christie than full-blown noir. It throws together a colorful assortment of cliché Broadway luminaries, bigwigs, hangers-on, and bohemian

Greenwich Village types, then stands back as this close-knit group of

professional pretenders grows progressively unraveled by the inconvenient intrusion

of a murder into their cloistered enclave.

While Black Widow is built around the noir staple of an innocent person having their life spiral out of control due to being falsely accused of a crime, missing-in-action is the hard-boiled dialogue and requisite climate of fatalism necessary to make this overlit whodunit feel like the real thing. Not helping matters is the fact that time which would have been better spent fleshing out character motivations and plot twists is given over to draggy amateur sleuthing that leans heavily on coincidence and relies too often on slow-witted police work.

|

| Skip Homeier as John Amberly |

At the periphery of this innocent but potentially combustible situation

are: well-heeled sister and brother, Claire and John Amberly (Virginia Leith and

Skip Homeier)--she a slumming Greenwich Village artist, he a law student; Nancy’s

uncle Gordon (Otto Kruger), a low-tier stage actor; Anne (Hilda Simms), Nancy's sharp-as-a-tack co-worker; Lucia Colletti (Cathleen Nesbitt), the

Denver's loose-lipped maid; and, once things take a nasty turn, Lt. Bruce (Raft), the steel-eyed, near-immobile detective.

The mystery at the core of Black Widow is handled fairly effectively, what with some throw-us-off-the-scent casting and a perhaps unintended lightness of touch helping to generate a few genuinely unexpected twists along the way. Also working in the film's favor is how the duplicitous and ruthless world of show business turns out to be a mystery-friendly environment

rife with the potential for homicide.

And I certainly can't find fault with the production itself, it being a veritable cavalcade of stagy sets, overdone fashions, and rife with what was apparently a '50s hair vogue: The poodle cut - those unflatteringly short perms resembling gold-hued bathing caps made of tense, lambswool curls.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM |

| Otto Kruger as Gordon Ling |

And I certainly can't find fault with the production itself, it being a veritable cavalcade of stagy sets, overdone fashions, and rife with what was apparently a '50s hair vogue: The poodle cut - those unflatteringly short perms resembling gold-hued bathing caps made of tense, lambswool curls.

But in the end, neither the dark promise of the film's title, nor the camp excesses suggested by its gaudy visuals are ever realized in sufficient force to make Black Widow more than a handsomely mounted, slightly overdressed crime thriller.

It isn't

common for a film’s greatest strengths to be found in its weaknesses, but Black Widow is frequently at its most persuasive

when serving up a brand of moviemaking so glossily old-fashioned, its patently theatrical artificiality begins to take on the characteristic of something

resembling a style.

From the

outset, Black Widow embarks on a narrative course

endorsing a mode of dress (the crisp, stiff clothes look like costumes),

setting (95% soundstage, 5% NYC locations), and performance (all indication,

little believable emotion), all supporting the theory of a concentrated effort

on the film’s part to bear as little resemblance to real life as possible.

There's an alien "otherness" to the look of the film created by the lighting and composition requirements of the CinemaScope process. A process that turns New York into a sterile and oddly spacious environment (a basement Greenwich Village coffeehouse looks to be roughly the size of an airplane hangar) which puts it at direct odds with the kind of shadowy claustrophobia one associates with film noir.

I sound like I'm complaining, but honestly (and this may be mere perversion on my

part) I found the discordant visual tone to actually work to Black Widow’s advantage. Based on its initial scenes and not knowing anything about the film before I saw it, I thought

Black Widow was going to be a light romantic

drama. One of

those '50s “woman’s pictures” combining elements of All About Eve (Tallulah Bankhead was first approached for the

Ginger Rogers role), The Moon is Blue

(that film’s star, Maggie McNamara, was first choice for the Peggy Ann Garner

role), or a continuation of Rogers’ own Forever Female

(1953) - another age-centric rivalry set in the world of theater.

There's an alien "otherness" to the look of the film created by the lighting and composition requirements of the CinemaScope process. A process that turns New York into a sterile and oddly spacious environment (a basement Greenwich Village coffeehouse looks to be roughly the size of an airplane hangar) which puts it at direct odds with the kind of shadowy claustrophobia one associates with film noir.

|

| The sort of natural, laid-back blocking CinemaScope made necessary |

That these posh surroundings, pretty people, and harmlessly waggish conversations are setting the stage for a murder mystery took me totally by surprise. And so it remained throughout: Black Widow's key lit, musical comedy sheen works at such amusing variance with what one has come to expect from noirish suspense thrillers that it inadvertently serves as a device to keep the audience off balance.

PERFORMANCES

Beyond the musicals she made with Fred Astaire, I’m not

enough of a fan of top-billed Ginger Rogers to know if the divinely catty

character she plays in Black Widow is

as much a departure from type as it seems. She has always displayed a charming brassiness in films like Stage Door and Golddiggers of 1933, so perhaps this isn't that much of a stretch, but with Van

Heflin’s one-note performance and the obvious fragility of Gene Tierney (the actress was in the early throes of a

mental breakdown during filming), Ginger Rogers' flamboyant energy is a godsend. Plus, she gets all the best lines.

|

| In a role that amounts to little more than a bit part, Broadway actress Hilda Simms gives the most natural, convincing performance in the entire film |

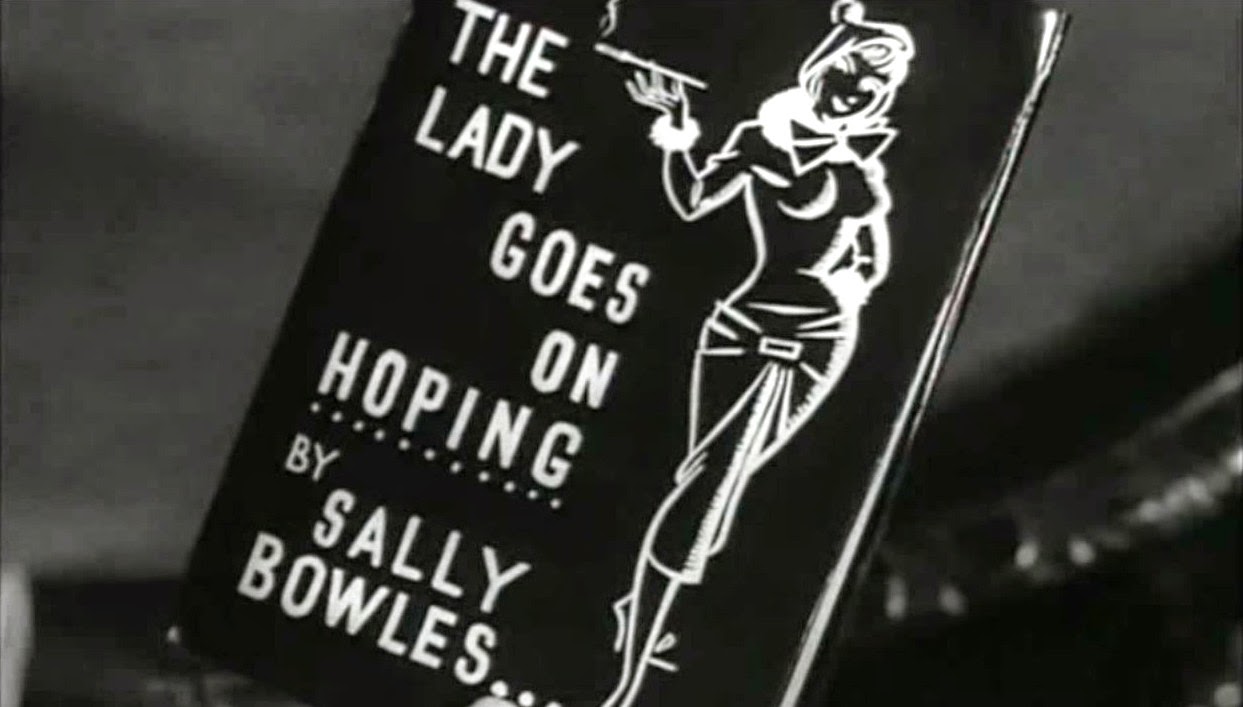

For former child star Peggy Ann Garner (A Tree Grows in Brooklyn), Black Widow was a a bid for adult legitimacy on par with Patty Duke's Valley of the Dolls...and it proved to be just about as successful. Given grief by critics at the time for not being a believable "type," I think she succeeds in the role chiefly for that reason. Garner's Nancy Ordway is a far more convincing babe-in-the-woods on the make than, say, Anne Baxter's brazenly transparent Eve Harrington in All About Eve.

|

| Pretty much the entire arc of Van Heflin's character |

To convey the grand style of the New York theater

folk at the center of Black Widow, 20th Century-Fox designer William Travilla whips up a drag queen's wet dream of ostentatious outfits for Ginger Rogers to parade around in. Happily, the longtime dancer is physically up to the task.

Carlotta - "To put the kindest face possible on it, the girl was a little

horror. A transparent, syrupy little phony with about as much to offer a man as 'cuckoo the bird girl.' Not even Peter with all of his radiant innocence about

women could have been stirred for one instant by that dingy little creep."

Peter - "Lottie, the girl is dead!"

Carlotta - "I know...and that’s precisely why I refuse to speak harshly of

her!"

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

For a movie written, produced, and directed by a single individual (Nunnally

Johnson of How to Marry a Millionaire, The Grapes of Wrath, The World of Henry Orient, etc.) Black Widow distinguishes itself by being almost completely lacking in distinction. Polished, well-made, and not nearly as vulgar as one might hope given the subject matter, Black Widow looks and feels like Hollywood product, circa 1954, that could have been directed by any number of studio contract professionals.

And perhaps that's why, for all its slick competence, Black Widow never coalesces into more than just a pleasantly diverting way to spend 95 minutes. A crime-of-passion movie without passion is a cold affair indeed, and Black Widow, while lovely to look at and fun in a detached sort of way (imagine absent-mindedly playing a game of "Clue") is ultimately most rewarding as a time-capsule view of Hollywood in its final years before it was forced to change in the mid-1960s.

Never intended to break new ground, Black Widow - a 40s noir retrofitted with color and CinemaScope - is but an example of 1950s Hollywood trying to hold onto its audience by giving them brighter and shinier versions of what they've always given them. Sorta like today today's digital, HD, CGI, 3-D opuses.

|

| The tall, lanky fellow holding his hat is future TV producer Aaron Spelling. Gene Tierney's health problems while making Black Widow necessitated her being seated in virtually all of her scenes |

Never intended to break new ground, Black Widow - a 40s noir retrofitted with color and CinemaScope - is but an example of 1950s Hollywood trying to hold onto its audience by giving them brighter and shinier versions of what they've always given them. Sorta like today today's digital, HD, CGI, 3-D opuses.

The black widow,

deadliest of all spiders, earned its dark title through its deplorable practice

of devouring its mate.

Copyright © Ken Anderson

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)