I really miss the old days when late-night television used

to be a film fan’s oasis of the great, near-great, and downright worst of what

Hollywood had to offer. My lifetime love of film is a direct result of an equally lifelong battle with sleep, and the broad assortment of old movies that kept me company (on non-school

nights, anyway) on The Late Show and The Late Late Show. There were no high-flown designations of “classic” films or "encore" broadasts then; they were merely

“old movies” and “reruns.” The scope and variety of said films was so vast, one could watch Geraldine Page in Toys in the Attic at 11:00pm, Mamie Van

Doren in Girls Town at 1:00am, and

see in the morning with Joan Crawford in Dancing

Lady at 3:00am.

TV stations had lots of airtime to fill, lots of used-cars to sell, and sizable packages of obscure and forgotten films of all stripes to do it with. Although I could have done without the commercial interruptions every five minutes, this unaccredited course in The Insomniac’s Film School provided a priceless education.

A particular Late Show favorite that has been popping up recently on cable TV is The Right Approach. It's another one of those "rips the lid off the garbage can" show biz exposeé movies that Hollywood seems to enjoy churning out. Films that attempt to shed light on, usually through overstated cliché and melodrama, the ruthless backbiting and treachery that so often accompanies a star's climb to the top. These sort of movies bank on show business having a sleazy kind of allure allure for the audience, yet after 90 minutes trumpeting glitz and glamour, always end up touting the simple virtues of decency and a good heart. Striving for up-to-the-minute daring, The Right Approach dates itself instantly (and hilariously) with its profusion of swingin’ Sixties Rat Pack-era “ring-a-ding-ding” hipster slang, and each turn of its defanged, What Makes Sammy Run? meets The Sweet Smell of Success plotline. Ranking high on my “so bad it’s good” guilty-pleasure trash-o-meter, The Right Approach simply begs for a DVD release.

This unaccountably forgotten camp treasure from 1961 has the look and feel of the bargain-basement, but it has a pretty snazzy pedigree. It’s based on an early, not very well-received play by Garson Kanin (Born Yesterday, Adam’s Rib) titled The Live Wire; it was adapted for the screen by Garson’s brother Michael Kanin and sister-in-law Fay (The Opposite Sex, Friendly Fire); it features a song by the award-winning songwriting team of Marilyn and Alan Bergman (The Way We Were, You Don’t Bring Me Flowers); and has a cast full of actors who all must have been under contract at 20th Century-Fox at the time. Oscar-nominee Martha Hyer (for Some Came Running) appeared in Fox’s The Best of Everything (1959); Liverpool crooner Frankie Vaughan was hot off of the lamentable Marilyn Monroe musical, Let’s Make Love (1960); and the ever-watchable Juliet Prowse had nearly caused an international incident by getting under Nikita Khrushchev’s skin in Can-Can (1960). Like most every film released by Fox between 1953 and 1967, The Right Approach was filmed in CinemaScope, but perhaps Fox broke the bank with How to Marry a Millionaire, for this film is strictly economy class and shot in black and white...so atypical for a movie this light (with musical numbers, yet).

In a reversal of the usual all-girl formula of films like The Pleasure Seekers, Valley of the Dolls, and The Best of Everything; The Right Approach tells the story of five bachelor buddies rooming communally in a reconverted Hawaiian restaurant high in the Hollywood Hills. There’s med student, Bill; barber-to-be Mitch, aspiring set designer, Horace; jazz musician, Rip; and I-have-absolutely-no-idea-what-he-does, Granny (yes, Granny is a dude). What becomes instantly obvious is that all are at least a decade too old for this kind of boyish, clubhouse arrangement, with Bill, the most glaringly elderly of the bunch, the only one afforded a backstory (military service and familial self-sacrifice) explaining away his late-bloomer status.

Into this happy, pentamerous setting comes Mitch’s older brother Leo, a caustic, wannabe singer /actor of near-supernatural amorality. A lying, cheating, self-interested, double-crossing, womanizing opportunist decades before these character flaws became standard equipment for reality TV stardom; Leo’s poisonous influence on The Hut (as the “boys” have dubbed their digs) and the lives of the ladies he comes into contact with provides both the drama and moral of The Right Approach. And, might I add, it also provides a great deal of the unintentional comedy. Bad boys and bad girls are the real heart of any showbiz drama, and in Frankie Vaughan’s Wile E. Coyote interpretation of Leo Mack, The Right Approach has one doozy of villain. Cross Patty Duke as Valley of the Dolls’ Neely O’Hara with Stephen Boyd’s Frankie Fane in The Oscar (1966) and you have some idea as to the camp histrionic heights this film can reach in its brisk 92 minutes.

PERFORMANCES

I don't know much about UK star Frankie Vaughan and will probably have to appeal to Our Man in the UK (Mark at Random Ramblings, Thoughts & Fiction) to perhaps provide me with some history. All I know is that I so soured on him in Let's Make Love (not his fault, I just hated Marilyn and Montand so much in that one) that his deliciously nasty turn as the bad guy in The Right Approach came as something of a surprise. He's not much of an actor, but he is an energetic showman and has these great Snidely Whiplash eyes that dart about cartoonishly whenever he's about to do something underhanded. Fans of Let's Make Love will recognize that film's theme song as well as the title tune from Fox's The Best of Everything played frequently in this film's background.

I really got a kick out of Juliet Prowse in this. Playing a hard-boiled, gum-chewing hash-slinger even more amoral than Vaughan's character, she gives the film a lift whenever she shows up. Not as glacially classy as Martha Hyer (a Hitchcock blonde if there ever was one) Prowse has the lion's share of the film's smart-ass dialog, a terrific screen presence, that wonderful accent, and we even get to see her dance a little bit (albeit in a cramped, one-room apartment...but those legs!).

BONUS MATERIAL

In addition to all the above, The Right Approach is a lot of fun for some of the glimpes of early Los Angeles it provides.

Copyright © Ken Anderson

TV stations had lots of airtime to fill, lots of used-cars to sell, and sizable packages of obscure and forgotten films of all stripes to do it with. Although I could have done without the commercial interruptions every five minutes, this unaccredited course in The Insomniac’s Film School provided a priceless education.

|

| Frankie Vaughan as Leo Mack "I learned a long time ago: nobody looks out for Daddy if Daddy don't look out for Daddy!" |

|

| Juliet Prowse as Ursula Poe "You can marry a lot more money in five minutes than you could make in a lifetime!" |

|

| Martha Hyer as Anne Perry "I'm not desperate. I like my life...I go where I want, when I want. Men aren't all that important." |

|

| Gary Crosby ad Rip Hulett "You been beltin' that grape a little...eh, Daddy?" |

|

| David McLean as Bill Sikulovic "It isn't always what a person gets that's important. It's what he gives up to get it!" |

|

| Jesse White as Agent Brian Freer "Y'know you're a very good lookin' boy in my opinion. A red-blooded, he-man type!" |

|

| Jane Withers (yes, Josephine the Plumber) as Liz "Sue me, but whenever I meet one of those 'Personality Boys' I wanna hide the good silver!" |

A particular Late Show favorite that has been popping up recently on cable TV is The Right Approach. It's another one of those "rips the lid off the garbage can" show biz exposeé movies that Hollywood seems to enjoy churning out. Films that attempt to shed light on, usually through overstated cliché and melodrama, the ruthless backbiting and treachery that so often accompanies a star's climb to the top. These sort of movies bank on show business having a sleazy kind of allure allure for the audience, yet after 90 minutes trumpeting glitz and glamour, always end up touting the simple virtues of decency and a good heart. Striving for up-to-the-minute daring, The Right Approach dates itself instantly (and hilariously) with its profusion of swingin’ Sixties Rat Pack-era “ring-a-ding-ding” hipster slang, and each turn of its defanged, What Makes Sammy Run? meets The Sweet Smell of Success plotline. Ranking high on my “so bad it’s good” guilty-pleasure trash-o-meter, The Right Approach simply begs for a DVD release.

|

| Vaselined Vegas Lounge Lizard No, that isn't Valley of the Dolls' Tony Polar, but it might as well be. Like a great many male singers of the day, the late British pop star Frankie Vaughan was fashioned in the mold of Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin (complete with that weird, jaw-dislocating thing so favored by Sammy Davis, Jr. and Mel Torme.) |

This unaccountably forgotten camp treasure from 1961 has the look and feel of the bargain-basement, but it has a pretty snazzy pedigree. It’s based on an early, not very well-received play by Garson Kanin (Born Yesterday, Adam’s Rib) titled The Live Wire; it was adapted for the screen by Garson’s brother Michael Kanin and sister-in-law Fay (The Opposite Sex, Friendly Fire); it features a song by the award-winning songwriting team of Marilyn and Alan Bergman (The Way We Were, You Don’t Bring Me Flowers); and has a cast full of actors who all must have been under contract at 20th Century-Fox at the time. Oscar-nominee Martha Hyer (for Some Came Running) appeared in Fox’s The Best of Everything (1959); Liverpool crooner Frankie Vaughan was hot off of the lamentable Marilyn Monroe musical, Let’s Make Love (1960); and the ever-watchable Juliet Prowse had nearly caused an international incident by getting under Nikita Khrushchev’s skin in Can-Can (1960). Like most every film released by Fox between 1953 and 1967, The Right Approach was filmed in CinemaScope, but perhaps Fox broke the bank with How to Marry a Millionaire, for this film is strictly economy class and shot in black and white...so atypical for a movie this light (with musical numbers, yet).

|

| Because the system works; the system called reciprocity Mitch (Steve Harris) clips the locks of Bill (David McLean) who ties the tie of Rip (Gary Crosby) |

In a reversal of the usual all-girl formula of films like The Pleasure Seekers, Valley of the Dolls, and The Best of Everything; The Right Approach tells the story of five bachelor buddies rooming communally in a reconverted Hawaiian restaurant high in the Hollywood Hills. There’s med student, Bill; barber-to-be Mitch, aspiring set designer, Horace; jazz musician, Rip; and I-have-absolutely-no-idea-what-he-does, Granny (yes, Granny is a dude). What becomes instantly obvious is that all are at least a decade too old for this kind of boyish, clubhouse arrangement, with Bill, the most glaringly elderly of the bunch, the only one afforded a backstory (military service and familial self-sacrifice) explaining away his late-bloomer status.

Into this happy, pentamerous setting comes Mitch’s older brother Leo, a caustic, wannabe singer /actor of near-supernatural amorality. A lying, cheating, self-interested, double-crossing, womanizing opportunist decades before these character flaws became standard equipment for reality TV stardom; Leo’s poisonous influence on The Hut (as the “boys” have dubbed their digs) and the lives of the ladies he comes into contact with provides both the drama and moral of The Right Approach. And, might I add, it also provides a great deal of the unintentional comedy. Bad boys and bad girls are the real heart of any showbiz drama, and in Frankie Vaughan’s Wile E. Coyote interpretation of Leo Mack, The Right Approach has one doozy of villain. Cross Patty Duke as Valley of the Dolls’ Neely O’Hara with Stephen Boyd’s Frankie Fane in The Oscar (1966) and you have some idea as to the camp histrionic heights this film can reach in its brisk 92 minutes.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

We Americans are a celebrity-obsessed bunch who love to

romanticize the lives and careers of the rich and famous. All the while feeling the need to reassure ourselves (incessantly) that in spite of their

looks, wealth, and notoriety, the famous are a shallow, amoral

bunch without a shred of integrity or decency between them. Hollywood, an

industry that’s always known what side its bread was buttered on, has been more

than happy to feed this dysfunction with glitzy tales of fame idolatry disguised

as cautionary fables designed to placate the unwashed masses that all that unattainable,

envy-inducing glamour they've been waving in fron tof our noses is an

unworthy pursuit fraught with heartbreak, treachery, and compromised ideals. That these lacerating indictments of Hollywood’s

superficiality are made by individuals (directors, actors, writers) all seeking fame and fortune in self-said

industry doesn't strike anyone involved as a tad disingenuous probably

explains why these films always feel so false and over the top.

PERFORMANCES

I don't know much about UK star Frankie Vaughan and will probably have to appeal to Our Man in the UK (Mark at Random Ramblings, Thoughts & Fiction) to perhaps provide me with some history. All I know is that I so soured on him in Let's Make Love (not his fault, I just hated Marilyn and Montand so much in that one) that his deliciously nasty turn as the bad guy in The Right Approach came as something of a surprise. He's not much of an actor, but he is an energetic showman and has these great Snidely Whiplash eyes that dart about cartoonishly whenever he's about to do something underhanded. Fans of Let's Make Love will recognize that film's theme song as well as the title tune from Fox's The Best of Everything played frequently in this film's background.

|

| Change Partners That's Juliet Prowse, Robert Casper, Frankie Vaughan, & Martha Hyer. The Right Approach would have been really gangbusters if its couplings had gone the direction the gazes in this screencap hint toward. (Martha Hyer's giving Juliet Prowse one of those Candice Bergen looks from The Group.) |

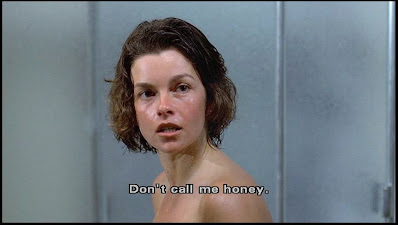

I really got a kick out of Juliet Prowse in this. Playing a hard-boiled, gum-chewing hash-slinger even more amoral than Vaughan's character, she gives the film a lift whenever she shows up. Not as glacially classy as Martha Hyer (a Hitchcock blonde if there ever was one) Prowse has the lion's share of the film's smart-ass dialog, a terrific screen presence, that wonderful accent, and we even get to see her dance a little bit (albeit in a cramped, one-room apartment...but those legs!).

|

| Ursula: "We're in trouble." Leo: "You're in trouble." Ursula: "How's that again?" Leo: "Who's the father?" Ursula: (Delivering a resounding whack across the chops) "THAT'S who!!" |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

With Russ Meyer dead, Paul Morrissey bitter, and John Waters gone corporate; it's growing near impossible to find solid camp these days. The Right Approach has all the requisite bad dialog, weak songs, cliched plotting, exaggerated performances and self-serious moralizing to make it a classic of the trash-with-class genre, but it is soooo hard to find. I still have my old pan and scan VHS TV copy from I don't know how many years back, but I would love to see this in widescreen. |

| Up To No Good |

BONUS MATERIAL

In addition to all the above, The Right Approach is a lot of fun for some of the glimpes of early Los Angeles it provides.

Copyright © Ken Anderson