All That Jazz is the movie I wish had inspired me to

become a dancer. Bob Fosse's artily stylized, semi-autobiographical, cinematic

dissertation on the artist as self-destructive skirt-chaser, is just the kind

of self-mythologizing fable that appeals to

the romantic notion of the fragility of the creative process.

All that Jazz is

the story of Broadway choreographer Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider); a pill-popping,

chain-smoking, serial-womanizing choreographer/director who struggles to prevent

the demons that fuel his creativity from consuming his life. Simultaneously

mounting a Broadway show and editing a motion picture, Gideon's intensifying

abuse of his health (both physical and mental) manifests, surrealistically, as a

literal love affair/dialog with death (a teasing Jessica Lange). Fosse makes no

effort to mask the fact that Joe Gideon is

Bob Fosse and All That Jazz is Fosse's 8½; but, as gifted as he is, Bob Fosse is no

Frederico Fellini. His essential shallowness of character (something he takes great pains

to dramatize in the film) makes for the baring of guardedly superficial

insights, leaving the larger philosophical questions of "what price

art?" unaddressed.

All That Jazz asks us to accept that Joe Gideon is selfish, an adulterer, a neglectful father, a philanderer, a manipulator, and a liar; but gosh darn it, at least he knows it! Nobody’s perfect, the film seems to be saying, but isn't a little of that imperfection mitigated by their ability to bring art into the world? What Gideon offers as a means of earthly penance for the pain he causes others, is his genius. And it's a point well-taken, for (at least to me) Fosse's choreography in All That Jazz is so brilliant as to justify almost anything. Almost.

I buy happily into the enduring romantic myth of the

tortured, suffering artist. The tortured, suffering artist as asshole? Not so

much. It seems to me a curiously male perspective that allows for the emotional collateral damage of a life of self-indulgence to be tolerated, and ultimately absolved, through one’s art.

(The female equivalent: the fragile, too-sensitive-for-this-world type, more

apt to do harm to herself than others.)

A legend on Broadway, director/choreographer/sometime-actor

Bob Fosse directed but three movie musicals (Sweet Charity, Cabaret,

and All That Jazz), yet their

influence on dance, the musical genre, and choreography for film has been far-reaching

and incalculable. Raked over the coals by critics for the stylistic excesses of

1969s Sweet Charity (Pauline Kael

went so far as to call the film "A disaster"); by the time these talents were honed and polished to a

fine gloss in Cabaret (1972), Fosse's

fluidly kinetic camerawork and slice and

dice style of editing eventually became the definitive visual style for

contemporary movie musicals.

What has always struck me about Fosse's dance style was how it was so perfect for the female form. If the lines of classic ballet celebrated the idealized feminine form— ethereal and untouchable—Fosse's sensuous style took women off the pedestal and celebrated her sensuality and reveled in her carnal vulgarity. Drawing from his days in burlesque, Fosse's style somehow sidesteps the passive, camp allure of the showgirl and captures an exhibitionistic hyper-femininity that carries with it a touch of danger. To watch the way Gwen Verdon moves as Lola in Damn Yankees is to see the pin-up ideal come to life. I've always thought that if a Vargas Girl portrait could move, she'd move like a Bob Fosse dancer.

PERFORMANCES

T he brilliance that is All

That Jazz pretty much extends to everything but the central conceit of the

plot (which somehow worked for Fellini and no one else. Rob Marshall's Nine was pretty dismal). Fosse gets

Fellini's cinematographer, Giuseppe Rottuno (Fellini Satyricon), to give the film a smoky sheen, the music is

sparkling, and the dreamy stylization employed throughout is sometimes

breathtakingly inventive. One just wishes they weren't in the service of such

meager emotional epiphanies.

As stated in an earlier post, the movie that actually inspired

me to abandon my film studies and embark on a 25-year career as a dancer, is the

legendarily reviled roller-skatin' muse project, Xanadu (1980). Don't

get me wrong... Xanadu, in all its

flawed glory, is, and always will be for me, an infinitely more joyous, emotionally

persuasive experience than All That Jazz ever was (those soaring notes

reached by ELO and ONJ on Xanadu’s title track could inspire poetry). It's

just that when one is recounting that seminal, life-altering moment wherein one’s

artistic destiny is met square-on, face-to-face, it would have been to be nice to be able to point to a

serious, substantive work like All That

Jazz, instead of a film dubbed

by Variety as being about, "A roller-skating lightbulb."

|

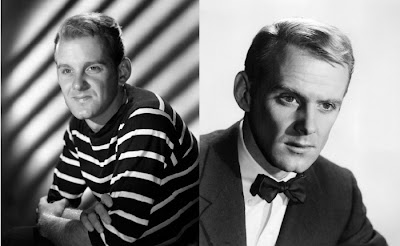

| Roy Scheider as Joe Gideon (a.k.a. Bob Fosse) |

|

| Jessica Lange as Angelique (a.k.a. The Angel of Death) |

|

| Leland Palmer as Audrey Paris (a.k.a. Gwen Verdon) |

|

| Ann Reinking as Kate Jagger (a.k.a. Ann Reinking) |

|

| Ben Vereen as O'Connor Flood (a.k.a. Sammy Davis, Jr.) |

|

| Director/choreographer Joe Gideon engaging in his other talent: disappointing loved ones. In this case, his daughter, Michelle (Erzsebet Foldi) a.k.a. Nicole Fosse. |

All That Jazz asks us to accept that Joe Gideon is selfish, an adulterer, a neglectful father, a philanderer, a manipulator, and a liar; but gosh darn it, at least he knows it! Nobody’s perfect, the film seems to be saying, but isn't a little of that imperfection mitigated by their ability to bring art into the world? What Gideon offers as a means of earthly penance for the pain he causes others, is his genius. And it's a point well-taken, for (at least to me) Fosse's choreography in All That Jazz is so brilliant as to justify almost anything. Almost.

And thus we land at what ultimately dissatisfies about All That Jazz for me.

It purports to be introspective, but at its heart, it’s apologist. Fosse isn’t

invested in getting to the root of what makes Gideon/Fosse tick, so much as pleading a

case for the redemptive power of artistic genius.

|

| "It's showtime, folks!" |

Although we're given scene after scene of Joe Gideon indulging in the

self-serving candor of the cheater (“Yes, I’m a dog, but I’m upfront about

it!”), these confessions never once feel emotionally revelatory. Rather, they recall this exchange from 1968's Cactus Flower-

(Walter Matthau's aging lothario prostrating himself before girlfriend

Goldie Hawn)

Matthau: I'm a bastard. I'm the biggest bastard in the

whole world!

Hawn: Julian, please...you're beginning to make it sound

like bragging.

Personally, I'm waiting for the day when someone will make a film that sheds

some light on what kind of women attach themselves to artistic, self-centered

men - never resenting having to play

second, third, or sixth fiddle - as they float, like interchangeable satellites, in

the orbit of genius.

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

If you haven't yet gleaned it, I'm not overly fond of the

autobiographical structure of All That

Jazz's plot. But much like the women who put up with Joe Gideon because he's

a genius of dance, I confess that I endure the clichéd narrative just so that I can enjoy the stupendous dance sequences. Bob Fosse is my favorite choreographer of all time, and

his work here is beyond splendid. It's absolutely amazing, and among the best

of his career.

What has always struck me about Fosse's dance style was how it was so perfect for the female form. If the lines of classic ballet celebrated the idealized feminine form— ethereal and untouchable—Fosse's sensuous style took women off the pedestal and celebrated her sensuality and reveled in her carnal vulgarity. Drawing from his days in burlesque, Fosse's style somehow sidesteps the passive, camp allure of the showgirl and captures an exhibitionistic hyper-femininity that carries with it a touch of danger. To watch the way Gwen Verdon moves as Lola in Damn Yankees is to see the pin-up ideal come to life. I've always thought that if a Vargas Girl portrait could move, she'd move like a Bob Fosse dancer.

PERFORMANCES

Fosse elicits many fine performances from his cast. Roy

Scheider, a non-dancer, is surprisingly good, displaying an easy charm behind a

keyed-up physicality that makes him believable as a dancer and object of

masochistic female affection (my heart blanches at the thought of originally-cast Richard Dreyfuss in the role). Leland Palmer is perhaps my favorite; a fabulous

dancer and one of those actresses whose edgy quality makes you keep your eye on

her even when she's not pivotal to the scene.

No surprise that Ann Reinking is a phenomenally talented dancer and truly a marvel to watch, but it's nice that she also displays an easy, husky-voiced naturalness in her non-dancing scenes. Jessica Lange has had such an impressive career that it's easy to forget her debut in King Kong (1976) almost turned her into the Elizabeth Berkley of the '70s. Wisely turning her back onHollywood

No surprise that Ann Reinking is a phenomenally talented dancer and truly a marvel to watch, but it's nice that she also displays an easy, husky-voiced naturalness in her non-dancing scenes. Jessica Lange has had such an impressive career that it's easy to forget her debut in King Kong (1976) almost turned her into the Elizabeth Berkley of the '70s. Wisely turning her back on

|

| Flirting with Death |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

In the book, On the

Line: The Creation of A Chorus Line, the collective of authors (several members of the

original Broadway cast) recall how, after several years of film treatments,

director/choreographer Michael Bennett was unable to land on a satisfactory

method to translate his show to the screen. All involved in A Chorus Line thought that Fosse

had, for all intents and purposes, beat

them to the punch and delivered (in a virtuoso eight-minute opening sequence),

everything that a screen adaptation of A

Chorus Line should have been. And indeed, the opening of All That Jazz is a matchless example of film as storyteller. It's

so perfect, it's like a documentary short.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

I'm crazy about all of the dancing in All That Jazz. Understandably, most people recall the remarkable "Take Off With Us/ Air-otica" number, but I

have a particular fondness for "Bye Bye Love/Life" number that ends

the film. A fantasy fever dream/nightmare taking place in the mind of Joe

Gideon as he slips away on a hospital bed, this number is outrageous in concept

and phenomenal in execution. We're in Ken Russell territory when you have a

dying man dressed in sequins (complete with silver open-heart surgery scar) singing

his own eulogy to an audience of everyone he's ever encountered in his life,

while flanked by gyrating dancers dressed as diagrams of the human circulatory system.

WOW!

I never tire of watching this number, as it appeals to both

the dancer and film enthusiast in me. Fosse, whose signature style consisted of

small moves, isolations, and minimal gestures, always seemed better suited to

the movies than the stage. He ushered in the use of the camera and editor as

collaborative choreographers, punctuating the rhythms and drawing the eye to

the details.

Bob Fosse died in 1987, mere months after the death of

his closest professional peer/rival, Michael Bennett. Broadway and dance suffered a loss that year that I don't think it has ever recovered from. Bennett didn't live long

enough to leave his stamp on cinema, but lucky for us, Fosse left a recorded

legacy that represents the best of cinema dance as art. "Thank you" doesn't begin to cover the debt of gratitude.

|

| Bye-Bye, Love |

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2011