|

| "I don't believe God is dead, but I do think he is inclined to pointless brutalities." Tennessee Williams |

Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton made a total of ten films together (11 if you count the presciently-titled 1973 TV-movie Divorce His/Divorce Hers) over the course of their highly-public, passionate-but-rocky, ten-plus-one-years marriage (wed in 1964, they divorced in ’74, remarried a year later,

re-divorced a year after that). By the time they appeared in their

8th vehicle together, Joseph Losey's Boom!, unkind film critics--worn down by years of ceaseless press

coverage of the couple's top-of-the-line lifestyle and bottom-of-the-barrel movie resume--had taken to referring to the paparazzi-popular pair as a traveling vaudeville

act. A difficult point to argue against at the time.

Branded infamous for their scandalously out-in-the-open, adulterous canoodling during the making of Cleopatra (1963), the combination of gossip and public curiosity helped turn cinematic dogs like 1963s The VIPs (neither had secured divorces from their respective spouses by then) and the following year’s The Sandpiper (their first onscreen pairing as man and wife) into boxoffice blockbusters. Yet it wasn't long after scoring an unexpected critical and boxoffice bullseye in Mike Nichols’ film adaptation of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966), that Taylor and Burton developed the reputation for saying yes to any film offer that promised a hefty payday, major tax break, or exotic locale in which to work.

Boom! offered all three, plus the prospect of granting Taylor an unprecedented Tennessee Trifecta: Having already appeared in two successful Tennessee Williams screen adaptations—Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) and Suddenly, Last Summer (1959)—garnering Oscar nominations for both, surely reuniting with Williams for Boom! (working titles Goforth and Sunburst) would result in delivering the third cherry for a boxoffice jackpot.

In his diaries published in 2012, Richard Burton admitted that The Sandpiper—a substantial financial success, but critical flop—was a film both he and Taylor knew to be a joke, but accepted solely for the opportunity to work together and as a cash-grab of convenience should negative public opinion about Le Scandale lead to their never working again. On the topic of the $5 million mega-flop that was Boom!, Burton asserts that it was a film both he and Taylor very much believed in and very excited to do. In fact, after watching dailies mid-production, Burton writes of the film looking “perverse and interesting,” and optimistically intones, “I think we are due for another success, especially E [Elizabeth].” Given the dismal returns on their most recent releases The Comedians (1967) and Doctor Faustus (1967), perhaps the words "long overdue" are more apt.

|

| Elizabeth Taylor as Flora "Sissy" Goforth |

|

| Richard Burton as Christopher Flanders |

|

| Noel Coward as Baron William "Billy" Ridgeway, aka The Witch of Capri |

|

| Joanna Shimkus as Francis "Blackie" Black |

|

| Michael Dunn as Rudi |

Elizbeth Taylor is eccentric millionairess Flora (“All my close friends call me Sissy”) Goforth. Cloistered away in a majestic mountaintop villa on her private island in the Mediterranean, Sissy Goforth dictates her alternatingly introspective/self-aggrandizing memoirs to her put-upon secretary (Joanna Shimkus) while being overzealously watched by her sadistic bodyguard Rudi (Michael Dunn). It’s summer (isn’t it always in a Tennessee Williams movie?) and Signora Goforth is dying. But not to hear her tell it.

After burying six husbands--five wealthy industrialists and a penniless poet/adventurer who was the love of her life--the widow Goforth fancies herself as an indefatigable force of nature and nothing less than eternal. And, in point of fact, after getting a load of her constant carping, bellowing, and hurling of coarse invectives at all and sundry, one can well imagine that even death itself, when faced with the prospect of coming face-to-face with Flora Goforth, might opt to pass her by.

|

| In 1968 Boom! and Rosemary's Baby earned the dubious distinction of being the first American feature films approved by the MPAA (Production Code Seal) to feature the word "shit." |

"The doctors are disgusted with my good health!” Flora insists. Even in the face of nightly pain injections, blood transfusions, regular vitamin B shots, a steady diet of pills and medications, and the distressing increase in the number of paper roses blooming in all corners of the villa (a paper rose is Flora's bleakly poetic name for the many discarded wads of tissue stained with her coughed-up blood.)

But for all that money can buy, it can't buy immortality, so the gravely ill Flora Goforth...racing against time to complete her memoirs...is fated to go forth from this plane of existence. But not until she’s good and ready. And ready she’s not. The "dying monster," as she's referred to by her scornful staff, is not yet willing, prepared, or capable of relinquishing her vicelike grip on life. Or, closer to the truth, that which has come to represent life tor her: wealth, power, possessions, position, acquisition, and excess.

|

| The Walking Dead By way of her vulgarity, cynicism, lack of compassion, and ostentatious flaunting of wealth, it's inferred that Flora Goforth's spiritual death occurred long ago. |

As though metaphysically summoned, a trespassing stranger

named Christopher Flanders (Richard Burton) arrives at the villa carrying two heavy

bundles and professing to have been invited. Flanders, whose saintly Christian

name proves to be as symbolically relevant (and subtle) as Flora’s surname, is

an itinerant poet, mobile artist, aging gigolo, and professional houseguest. Most recently, among his circle of imposed-upon jet-set friends, he has come to be known as “The

Angel of Death.” A bitchy-but-accurate name assigned to him after a pattern emerged involving his paying visits to some of his aging and ailing benefactors shortly before their deaths.

With Christopher’s arrival, the already sublimely bizarre Boom! takes on the form of a spiritual allegory played out in a highly-stylized manner suggesting a Western interpretation of Eastern kabuki theater. Flora, facing mortality by stubbornly ignoring its existence, clings ever tighter to what she wants. Meanwhile, Christopher, whose physicality inflames Flora’s lifelong use of sex as a means of denying death, dares to suggest that beyond the things she wants lie the things she actually needs.

|

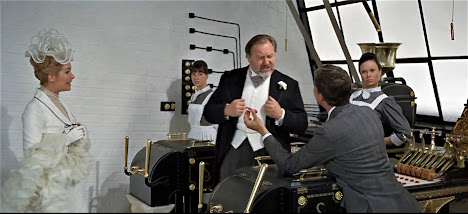

| Taking advantage of a little breather between Goforth tantrums, her houseman Etti (Fernando Piazza) and her attending physician Dr. Luilo (Romolo Valli) |

In his 1975 memoir, Williams relates that he was

both astonished and overjoyed when the film rights for The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore had been purchased and director

Joseph Losey (The Servant) assigned to the project: “Then a dreadful

mistake was made. [Producer Lester] Persky offered the film to the

Burtons.”

Were I the gambling type, I’d wager that the very reasons Tennessee Williams saw the Burtons as the least-favorable casting option for Boom! are the very reasons I find them to be absolutely ideal for the material. The stunt-miscasting of Taylor & Burton in Boom! was a bald-faced effort to try and recapture the lightning-in-a-bottle magic of Mike Nichols’ “And you thought she/he was all wrong for the part!” Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? hat trick, while simultaneously exploiting the screenplay's many Taylor-related bits of self-referential coincidence. Flora was supposed to be a past-her-prime battleax grinding to a halt in her 60s (Taylor was 35), Chris a fading gigolo in his early 30s (Burton was 42). Neither really fit their roles in ways having nothing to do with their ages, but say what you will, Taylor's mesmerizingly purple performance abutted by Burton's Sunday-morning-hangover thesping are the sole and primary reasons Boom! achieves any level of watchability at all.

|

| Chris: (Indicating cigarette) "May I have one?" Flora: "Kiss me for it." |

But I’m the first to admit that the Boom! I adore is probably not at all the Boom! Losey & Co. set out to make. As a play cloaked in Brechtian minimalism, it reads like a needlessly convoluted rehash of themes Williams has already explored…with more poignance and coherence…in Sweet Bird of Youth, The Fugitive Kind, Summer and Smoke, and The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone. As a film, not only does Williams’ trademark brand of cloaked symbolism and Freudian metaphor sound cobwebby in the era of “tell it like it is,” but no one involved in the project seemed aware that high-minded drama and high glamour have a funny way of canceling each other out. The end result is like watching a Theater of the Absurd sequel to Valley of the Dolls dramatizing the final days of Helen Lawson.

|

| Since Mrs. Goforth on her deathbed looks better than most people in the full bloom of health, it's kinda hard to wring much pathos out of her plight. |

Representing murky ideologies rather than people, the king-size

personalities of Burton and Taylor, left with no characters to inhabit, resort

to playing exaggerated versions of themselves. Portraying Death and often

looking like it, Burton staggers about while letting his trained voice do all

the heavy lifting. Meanwhile, Taylor, tottering around in high heels and even

higher hair, plays Flora Goforth as a female impersonator doing a burlesque of Elizabeth

Taylor. Yet they’re impossible not to watch. The film's sole concession to a contemporary sensibility is achieved in having a character written as a gossipy queen actually played by one. The Witch of Capri is traditionally played by a woman, and the producers had hoped to snare Katharine Hepburn. But granting the role to famed playwright/composer Noel Coward is inspired if ultimately affectless.

Robert Redford portrayed Death as a kind young man who comes to ease an old woman’s (Gladys Cooper) fear of dying in the 1962 episode of The Twilight Zone titled "Nothing in the Dark."

|

| Divine Intervention A favorite blogger writes about BOOM! as drag inspiration HERE |

|

| BOOM! opened on Wednesday, May 29, 1968 at Hollywood's Pantages Theater. |