Spoiler Alert: Crucial plot points are revealed in the interest of critical analysis and discussion

Somewhere beyond the boundaries of the healthy, adaptive kind of Cultural Paranoia that I, a Black gay man, accesses daily to navigate hostile environments of discrimination and racial bias; on the far side of whatever amorphous fears are harbored by the kind of people who routinely dress in fatigues and buy anything with the word “Tactical” on the packaging; past the limits of the alternately narcissistic/masochistic borders of “Everyone’s out to get me!” delusional paranoia…there lies the macabre Twilight Zone that is Roman Polanski’s brilliant The Tenant. A bizarre, Kafkaesque exploration of social alienation and encroaching madness that film critic Vincent Canby accurately described as a nightmare vision of “Emotional isolation that becomes physical.”

Adapted for the screen with almost religious faithfulness by Polanski and longtime collaborator Gerard Brach from the 1964 novel Le Locataire Chimérique by Roland Topor, The Tenant marks the Academy Award-winning director’s 9th feature film. It also marks what many consider to be the third and final entry in his unofficial Urban Paranoia Trilogy (aka, his Apartment Trilogy): Repulsion – 1965, Rosemary’s Baby – 1965, & The Tenant – 1976.

For his part, Polanski flatly denies ever deliberately setting out to make a contemporary terror triptych. But admirers of his work have seized upon the thematic recurrence in these films of many of the director’s most fervent obsessions: paranoia, alienation, sex, psychosis, subjective reality, and cramped dwellings. Each film in the trilogy is a modern-gothic study of urban dread set in a different, obliquely-threatening, impersonal city (London, Manhattan, and Paris, respectively). Their eerie narratives unfold largely within the oppressive confines of decaying apartment structures, wherein rooms take on the character of four-walled prisons-of-the-mind, mirroring the progressive mental deterioration of their psychologically isolated protagonists.

The lead character in The Tenant is male (Polanski himself, his 3rd on-screen appearance in one of his own films), signifying the trilogy’s sole departure from having a woman as the central focus of a storyline.

It's neither coy nor misleading when I say that The Tenant does not disrupt the gender prominence of the trilogy.

.png) |

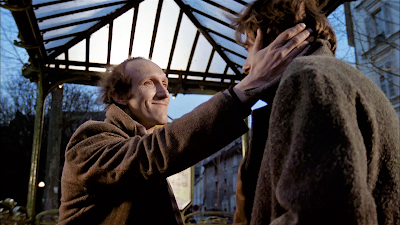

| Roman Polanski as Trelkovsky |

.png) |

| Isabelle Adjani as Stella |

|

| Shelley Winters as The Concierge |

|

| Melvyn Douglas as Monsieur Zy |

|

| Jo Van Fleet as Madame Dioz |

|

| Lila Kedrova as Madame Gaderian |

There's a scene in the movie musical On a Clear Day You Can See Forever where Barbra Streisand—as wallflower go-a-longer Daisy Gamble—discloses to hypnotherapist Yves Montand the results of a vocational guidance test: "Healthy, adjusted, and no character. I mean, no character of any kind. I mean, not even any…characteristics!”

Well, that describes The Tenant's Monsieur Trelkovsky in a nutshell. Trelkovsky, a soft-spoken Polish-born office clerk of indeterminate disposition who continually has to remind people he’s a French citizen, is a fellow who tiptoes through life as though he holds only a month-to-month tenancy on his own body.

During what can only be assumed to be a severe mid-‘70s Parisian housing shortage, Trelkovsky is so desperate for lodgings that he pursues—with a self-interest bordering on the ghoulish—the not-yet-vacated apartment of a not-yet-dead attempted suicide. The tenant, a young Egyptologist named Simone Choule, threw herself from the window of her flat just days before and now lies in a coma at a nearby hospital.

Faced with a moral conundrum (his wish to acquire the apartment is the silent, simultaneous wish that she won’t recover), Trelkovsky, in a gesture bearing the outward appearance of sympathy, but could just as likely be a cagey "calculation of probability" field trip—visits Mlle Choule in the hospital. Wrapped head to toe in bandages, the Egyptologist indeed looks like a mummy herself, with nothing of the woman beneath visible save for a single staring eye and a gaping mouth from which a tooth is conspicuously, grotesquely missing.

|

| Presented as though it were a bonus feature of the apartment, the concierge shows Trelkovsky the hole Simone Choule's body made in the glass awning four stories below |

Simone Choule dies shortly after this visit (brought to a jarring conclusion when the patient lets out a soul-rattling scream at the sight of the stranger at her bedside). And Trelkovsky—pragmatically heedless of any possible bad omens augured by gaining advantageous self-benefit at the price of another's misfortune—wastes no time moving into the apartment. An apartment that hasn’t yet been entirely cleared of the dead woman’s possessions.

Early scenes show Trelkovsky getting what he wants by adopting a persona of over-polite inoffensiveness (e.g., he finesses the bulldoggish concierge by paying her a gratuity and placates the surly landlord by appealing to his financial practicality). These passively assertive acts suggest that perhaps Trelkovsky’s outwardly suppressed identity is more of an adaptive skill; a tool a Polish émigré hones in a city where being “foreign” instantly brands one a target of suspicion and distrust.

Presuming that a certain characterlessness and malleability of personality are what Trelkovsky has always relied upon as a survival mechanism to go about life as unobtrusively as possible; The Tenant effectively puts the turn to the screw by making this quality in Trelkovsky...a “vacancy of self”...the tragic flaw that will come to seal his fate.

|

| Though interested in Simone's friend, Stella, Trelkovsky, by lying about knowing Simone and keeping his occupancy of her apartment a secret, must keep part of his true identity hidden. |

The apartment building Trelkovsky now calls home can be summed up by a term coined in Woody Allen’s Manhattan Murder Mystery; a neurotic’s jackpot. Almost immediately after moving in, Trelkovsky begins to suspect every tenant of being a furtive, inhospitable oddball who, when not lodging noise complaints about his every move; monitoring his comings and goings; or staring into his apartment from windows across the courtyard, is working in concert in a plot to get him to somehow become Simon Choule and give an encore performance of her dramatically gravitational exit.

But after an incident at Simone's funeral (where his sexual guilt turns a eulogy into a fire and brimstone lambaste), it's apparent Trelkovsky isn't what you'd call a reliable narrator.

Thus, The Tenant builds suspense by sustaining a disconcertingly ambiguous tone throughout. One is never quite sure whether Trelkovsky's horrors are psychological (a mental breakdown), sociological (xenophobia), or supernatural (anyone for a mummy’s curse?)

|

| Trelkovsky: Tomb Raider |

Clockwise from top left: 1. The mummified Simone Choule. 2. Trelkovsky receives a postcard of an Egyptian sarcophagus. 3. In a hallucinative state, Trelkovsky sees Egyptian hieroglyphs on the building’s communal bathroom wall. 4. Trelkovsky is given one of Simone's books, The Romance of a Mummy by Théophile Gautier (1858).

Simone being an Egyptologist, rather than merely being a bit of backstory info about the former renter, becomes a prominent theme underscoring the somewhat paranormal shift The Tenant takes in its second act. The fact that so many of Simone Choule’s left-behind items (books, drawings, sculpture) reflect her interest and immersion in the culture of ancient Egypt makes Trelkovsky’s swift occupancy of her apartment feel as though he’s somehow disturbing the resting space of the deceased. Similarly, the Egyptian belief in immortality, with its attendant burial rituals devoted to preserving the body and the soul's rebirth, finds its queasy contemporary correlative in Simone Choule’s medical mummification. Swathed in bandages, Simone and her staring eye and missing tooth horrifically reference the Egyptian “opening of the mouth” ceremony; a rite performed to return the human senses to the soul in the afterlife.

|

| Self-Alienation / Fragmented Identity |

Trelkovsky’s “possession” by Simone is entirely superficial (he gains absolutely no insight into the woman’s self) signaling his metamorphosis is more a self-generated delusion than an act of actually "becoming" Choule. Amounting to little more than the appropriation of only the most external signifiers of Simone's identity—clothes, makeup, cigarettes, hot chocolate, books—Trelkovsky turning into Simone feels less like The Tenant seeking to explore the flexible quadrants of gender and more like surrealists Topor and Polanski merely attaching existential theory to the question "Do clothes make the (wo)man?"

In Rosemary’s Baby, Polanski toyed with the notion of ancient evil (pagan witchcraft and Satan worship) surviving into the 20th century. A similar vein is mined in The Tenant’s paralleling of Egyptian mythology (immortality and the dominance of the soul in determining self) with the dissociative aspects of modern urban life (the separate-yet-together existence of apartment-dwelling) that prioritize the individual. I.e., a civilization that values holed-up privacy, solitude, keeping to oneself, and minding one’s own business can foster relativism and the solipsistic view that the mind alone is sovereign of the self.

But if the mind is the sole determiner of self, is each person then ruled by their own individual perception of reality?

Heads, attached and disembodied, figure as a motif in The Tenant. Ceramic busts appear in the apartments of Trelkovsky (Egyptian, of course) and Mr. Zy. Trelkovsky has a hallucination that his neighbors are playing football with a human head (Simone's or his own) in the courtyard

|

| A drunk Trelkovsky ponders the philosophical, metaphysical, and mythical concepts of "self" |

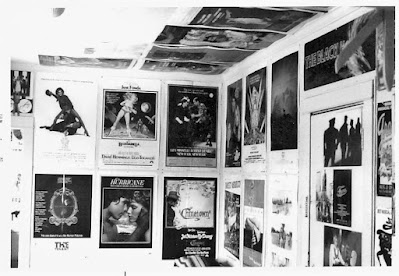

The Tenant premiered at The Regency Theater in San Francisco in the summer of 1976, and I was beyond excited to see it. Expectations were high, as it had been two years since the release of Chinatown. The Tenant’s chilling teaser trailer (with the soon-to-be-unfortunate tagline “No one does it to you like Roman Polanski”) promised a welcome return to type from the director who scared the hell out of me when I was eleven with what was then...and still remains...my #1 favorite motion picture of all time: Rosemary’s Baby.

|

| The Wide-Angle Distorted Perception Peephole Shot Repulsion - Rosemary's Baby - The Tenant |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

It's not overstatement when I say The Tenant had me from the jump (pun possibly intended). After the sun-baked Southern California vistas of Chinatown, I was delighted with Polanski’s return to creepily claustrophobic interiors, menacing old people, and his lived-in, off-kilter brand of psychological horror. A movie that hits the ground running—with a dizzying, voyeuristic panning shot of apartment windows, revealing shifting glimpses of both Trelkovsky and Simone Choule staring through curtains at “the real(?)” Trelkovsky entering the courtyard to inquire about the availability of the apartment he already appears to be occupying—The Tenant is a film that wears its weirdness on its sleeve.

Given invaluable, atmospheric assist by Swedish cinematographer Sven Nykvist and French composer Philippe Sarde, Polanski, in adapting Roland Topor’s novel, proves, as he did with Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby, he's adept at making someone else's nightmares seem as though they originated out of his own well-stocked store of personal demons and obsessions. Sharing Topor’s outsider's eye for finding the ominous in the ordinary (both are Paris-born sons of Polish-Jewish immigrant parents), the close-quarters dictates of The Tenant's setting allow Polanski to indulge his trademark canniness in turning living environments into starkly-rendered extensions of a character’s inner dread.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Psychological thrillers about personality theft, duality, and the fluidity of identity have fascinated me…forever. Especially when they spill over into possible supernatural/horror territory. Growing up the only boy of five children, parents divorced/mom remarries, Catholic school, gay, shy, and the only Black family in an all-white neighborhood gave me a leg-up in the “Who the fuck am I?” adolescent identity sweepstakes. So, films were my retreat, and movies that (melo)dramatized the puzzle of self: Vertigo (1958), The Servant (1963), Secret Ceremony (1968), Performance (1970), Images (1972), Obsession (1976), 3 Women (1977), Fedora (1978), Dead Ringers (1988), Single White Female (1992), and Black Swan (2010)—were my catharsis.

My recently having had the opportunity to read the novel prompted my partner and me to watch The Tenant last Halloween. My first time seeing the film in several years. This time out, I was struck by how many of the persecutory torments pushing Trelkovsky to the brink of madness (being persistently watched, always having his behavior monitored, instantly being branded a target of suspicion, prejudicially profiled, having his experience invalidated) is kinda like an average day for a Black person living in America. The terrorism of racism and "Living While Black" has always resulted in feelings of alienation, isolation, and anxiety among Black people, and movies like The Tenant have been a means of accessing those fears in a broad, generalized context. However, it wasn't until the release of 1995's Tales from the Hood by Rusty Cundieff, and Jordan Peele's Get Out (2017) that I ever saw a director illuminate the anxieties particular to racism and unique to the Black Experience in this country in the form and context of the horror genre.

|

| The American cast members of The Tenant |

PERFORMANCES

Polanski started out as an actor (and never stopped, if all those behind-the-scenes photos of him “directing by demonstrating” tell the tale), so I wasn’t really surprised by how effective he is in the role of Trelkovsky. Casting himself very much to type, Polanski essentially IS the Trelkovsky of Topor’s novel...there being the shadow of something unsavory about him even at his most vulnerable. And he's particularly persuasive in conveying the anxiety and jumpy self-absorption that accompanies his character’s intensifying psychotic delusions.

I've no idea what motivated Polanski to cast so many American actors in major roles in this Paris-set thriller (likely financial in origin, to secure American distribution or wide release). But the overall effect is so discordant it actually feels intentional. The clashing of Trelkovsky’s faint Polish accent against all those flat Yankee diphthongs dramatically emphasizes his "otherness.". At the same time, the incongruousness of the glaringly non-Gallic Shelly Winters, Jo Van Fleet, and Melvyn Douglas only seem to add another layer of wacko to The Tenant’s existing Theater of the Absurd vision of Paris.

.png) |

| French cinema icon Claude Daupin makes a brief appearance (with Louba Guertchikoff) but his mellifluous accent is dubbed over with an affectless American voice |

|

| Although sorely underutilized, I adore Isabelle Adjani in The Tenant. I only recently learned that Adjani's voice was dubbed by Dark Shadows actress Kathryn Leigh Scott. Seen here with Sam Waterston in 1974's The Great Gatsby |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Polanski films are always rich in visual motifs, and The Tenant is no exception. The aforementioned Egyptian details, mummification references, and emphasis on all things cranial. Present, too, are his amplified ticking clocks and distorted perception shots of hallways and rooms (in particular, a fabulous fever dream sequence where Trelkovsky is dwarfed by the furniture in his room).

|

| La Peinture Lure (Hello, Google Translate) It seems Polanski hired Roland Topor to paint this mystifying poster that appears frequently and enigmatically throughout the film |

But in a film about paranoia, it's simply genius to have so many characters sporting those ginormous spectacles that were so popular in the '70s. They're like portable windows with magnified eyes staring out at Trelkovsky.

The Tenant is one of my top five favorite Roman Polanski films. It's an intriguing puzzle that yields a different solution every time I watch it.

BONUS MATERIAL

The First-Time Tenant

I moved to Los Angeles in 1978, and my very first apartment was a small furnished single on the second floor of The Villa Elaine Apartments in Hollywood. I was 20 years old, my first time away from home, and I couldn’t believe I was living within walking distance of THE Hollywood and Vine. The rent was $160 a month, including utilities, and I was in absolute heaven. Built in 1925, The Villa Elaine has since been declared a historical landmark. My old apartment now goes for $1650.

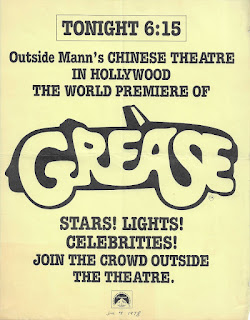

The day I moved into The Villa Elaine was Sunday, June 4, 1978. A date whose significance was compounded by what happened after I’d settled in and kissed my parents (who’d driven me and my blue storage trunk down from Berkeley for a weekend of whirlwind apartment-hunting) goodbye.

To exercise my freedom, I went out to look at my "new neighborhood." My walk took me to Hollywood Blvd., where the movie Grease was having its World Premiere at Mann's Chinese Theater. In those days, onlookers could stand and star-gaze in relative close proximity behind a velvet rope, so I was overjoyed at experiencing a real-life The Day of the Locust moment (minus the apocalyptic carnage) and screamed along with the rest when Olivia Newton-John and John Travolta arrived in a vintage car.

As I walked back to my apartment, the 1977 Rufus & Chaka Khan song “Hollywood” playing on a loop in my head; I was thoroughly over the moon. I couldn’t believe my first night in LA had serendipitously yielded such a quintessential, only-in-Hollywood experience. All of which I, of course, took as an omen that I had found my new home. And I guess it was; June 4th of 2023 will mark my 45th Anniversary as an LA resident.

|

| The Villa Elaine courtyard as it looks today |

I’ve lived in many apartments over the years, and I'm happy to say I've never had an experience even remotely similar to what’s in The Tenant.

Scene from "The Tenant" (1976)

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2023

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)