Spoiler Alert: Crucial plot points are revealed in the interest of critical analysis and discussion

Lipstick is a dramatized exposé and social critique on the serious topic of rape in the same way that Mommie Dearest is a dramatized exposé and social critique on the serious topic of child abuse.

For all its purported noble intentions and "socially conscious" pre-release hype, Lipstick, a slick, high-concept dramatic thriller with a whopper of an identity crisis, is a film that can’t help having its motives called into question. Since its release, Lipstick has suffered a public perception problem arising out of the cacophonous dissonance struck by the seriousness of its subject matter contrasted with the profound superficiality of its treatment.

Poised to be the first major motion picture to thoughtfully address the dual victimization women face in cases of sexual assault—the crime itself and, later, the "victim blaming" judicial system—Lipstick hoped to provoke the kind of cultural controversy and heated social conversations sparked by Martin Scorsese’s then recently-released Taxi Driver. But the only dialogue Lipstick prompted was widespread criticism of what many saw as a tasteless attempt to exploit a serious issue by using “social relevance” as a smokescreen for a routine rape-and-revenge flick.

And, indeed, audiences—unpersuaded by the film’s $3.5 million budget; team of legal technical advisors; and Oscar-adjacent pedigree…its cast included an Academy Award-winner (Anne Bancroft) and nominee (Chris Sarandon [Dog Day Afternoon]), its crew, Oscar-nominated cinematographer Bill Butler [One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest])—recognized Lipstick for what it was: an exploitation B-movie in A-list clothing.

Corner of Sunset and Larrabee

|

| Logo design by Sandy Dvore |

Producer Dino De Laurentiis, who scored a major hit with the Charles Bronson vigilante thriller Death Wish in 1974, hoped to land another jackpot with Lipstick. A movie that instead proved that you can take the exploitation flick out of the grindhouse, but you can't take the grindhouse out of the exploitation flick.

Critics (those wholly unacquainted with feminism, anyway) were quick to label Lipstick "A feminist Death Wish," while a bemused public, tasked with trying to make sense of a film so clearly at cross-purposes with itself, fractioned off into two distinct camps.

One camp comprised exploitation movie fans who enthusiastically embraced Lipstick's post-Billy Jack /neo-Taxi Driver zeitgeist and cheered the film's extravagant tawdriness and outrageously contrived (and outrageously satisfying) violent ending.

The second camp was individuals who detected in Lipstick’s advance publicity and early plot synopsis, similarities to the real-life legal cases of Joan Little and Inez Garcia—two women at the center of two headline-making, mid-’70s court trials in which the rape victim killed her assailant—and hoped the film would be an illuminating examination of the thorny issue of violence and victim’s rights. This was the group most disappointed and offended by Lipstick, voicing the common head-scratcher complaint /query: who thought it was a good idea to make a glossy, glamorous movie about rape?

Since American culture holds the not wholly inaccurate perception that the wealthy and beautiful are shielded from life's harsh realities, I think Lipstick, in choosing to have as its subject an uncommonly beautiful woman who makes her living off of the elevated status that comes with beauty, sought to dramatize that no woman or girl is invulnerable to the threat of violent sexual assault.

But somehow, that message didn't really seem to land.

"The built-in sensuality of the film medium presents a permanent dilemma: A director, even with good intentions, can hardly help turning a beautiful woman into a sex object, and there is always the danger that what starts out as an exposé becomes exploitation."

Molly Haskell, in her 1974 book "From Reverence to Rape: the Treatment of Women in the Movies."

Of course, there was a third camp—the word "camp" being particularly germane in this instance—who saw in Lipstick's earnest self-seriousness and heedless vulgarity a true cult film in the making. Normally, lovers of Bad Taste Cinema would have to look to the films of Andy Warhol, John Waters, or Russ Meyer to find a more preposterous co-mingling of haute couture, gratuitous nudity, sweaty-palmed villainy, flared nostril acting, and off-putting violence.

Not this time. If it can be said that Lipstick is in any way successful, I contend that it truly triumphs as an unintentional trash classic and an early contender for the title ascribed to Andy Warhol’s BAD the following year: “A picture with something to offend absolutely everybody.”

|

| Whose Gaze Is It, Anyway? Mr. Stuart cools his cobblers while making an obscene music phone call |

In telling its story, Lipstick plays fast and loose with just whose perspective we're afforded. In the early part of the film, the camera's gaze is actually more sympathetic to the rapist's experience. This is evident both in how the brutal assault is shot and in the ways its editing concerns itself with protecting the modesty of the assailant. All the while never missing an opportunity to expose the victim's nudity in sometimes startlingly crass tableau.

Were Lipstick even a marginally better-made film, I think I’d find it too disturbing (or offensive) to sit through. So I take it as a kind of mercy that it’s a movie that lavishes appreciably more imagination and care on its modeling sequences and fabulous disco synth soundtrack (by French composer Michel Polnareff) than on the darker implications of its central drama. It’s clear Lipstick strives for “ripped from today’s headlines” realism, but its melodramatic tone almost dares you to take it seriously.

|

| Margaux Hemingway as Chris McCormick |

.JPG) |

| Chris Sarandon as Gordon Stewart |

|

| Mariel Hemingway as Kathy McCormick |

.JPG) |

| Anne Bancroft as Carla Bondi |

.JPG) |

| Perry King as Steve Edison |

In a reversal of the standard ‘70s practice of made-for-TV movies borrowing the plotlines of then-current feature films, Lipstick’s plot has much in common with the groundbreaking 1974 TV movie A Case of Rape. Both films dramatizing how a woman’s thwarted efforts to put her rapist behind bars expose a judicial system that instead puts the victim’s life and sexual history on trial. But where the Emmy-nominated Elizabeth Montgomery TV film opts for a somber tone of social realism, Lipstick’s unsubtle approach prioritizes shock.

In a choice that seems to go against everything this film pretends to be about, screenwriter David Rayfiel gives Chris a brother who's a brother…or rather, a priest (played by John Bennett Perry, father of the late Matthew Perry). Given the size and inconsequence of the role, his presence feels like a tacked-on, tone-deaf signifier of Chris' virtue. The sexist "good girl" -"bad girl" moralizing behind antiquated rape laws is what this movie is supposed to be denouncing...not perpetuating.

Story: Model Chris McCormick (Margaux) agrees to meet with her 14-year-old kid sister Kathy’s (Margaux’s own 14-year-old kid sister Mariel) favorite teacher, Gordon Stuart (Sarandon), to listen to his experimental music compositions. Stuart ends up sexually assaulting Chris, but when charged with the crime, he convinces the court that it was consensual rough sex initiated by the sexually jaded plaintiff.

In the wake of the court’s Not Guilty verdict, Chris suffers losses both personal and professional. When Mr. Stuart targets Kathy in a second assault, big sister is forced to take matters into her own hands.

Despite Lipstick’s pervading tone of reality-challenged sensationalism, it does manage to make the occasional hamfisted point or two. Either by using Bancroft’s legal prosecutor character as a rape-statistics mouthpiece, or via the whittling down of complex issues into gratuitous setpiece moments calculated to provoke maximum audience outrage and catharsis.

But as a representative dramatization of what a distressing percentage of women go through, Lipstick is both too specific and too far-fetched to resonate as any sort of larger, relatable social indictment. Even the most obvious angle of social commentary available to the film—using the profession of modeling to explore the role that media and advertising play in perpetuating and normalizing rape culture—proves to be an opportunity largely squandered.

In an act of guerilla programming, filmmaker Martha Coolidge (Rambling Rose, Valley Girl, Introducing Dorothy Dandridge) released her debut feature Not a Pretty Picture—a sensitive semi-documentary about date rape—in New York on Wednesday, March 31, 1976…just two days before Lipstick opened in theaters on Friday, April 2nd. Though not widely seen then, critics hailed it for being, in execution, all that Lipstick sold itself to be.

Directed by Lamont Johnson (That Certain Summer - 1972) and written by David Rayfiel (Three Days of the Condor -1975), Lipstick was released in a surge of social relevance and pop culture topicality. The latter, courtesy of Margaux Hemingway, the 6-foot supermodel and granddaughter of Ernest Hemingway whose then-ubiquitousness (appearing on the cover of Time and landing a million-dollar contract with Fabergé Cosmetics, all in less than a year) made worthwhile the gamble of handing over the lead role in a major motion picture to an acting neophyte.

|

| I Found A Million Dollar Babe |

Cringe ads like these, promoting the dominance of the male gaze and implied proprietary physical access to women's bodies, were very common in the '70s. It was my hope that part of Lipstick’s agenda included exploring the role advertising plays in rape culture and normalizing the casual objectification of women.

Lipstick first came to my attention when I saw the movie's lip-shaped logo featured in a full-page teaser trade ad in Variety. Combining two of my favorite things—movies with one-word titles and movies with catchy slogans—I had no idea what any of it meant, but I was all in.

I took it as a hopeful omen that many of my recent favorites were movies with symbolic, single-word titles: Nashville, Smile, Shampoo. Plus, in a '70s movie landscape overcrowded with buddy films and male-centric stories, Lipstick felt like a signal heralding an emergence of more movies about women and featuring stronger female characters.

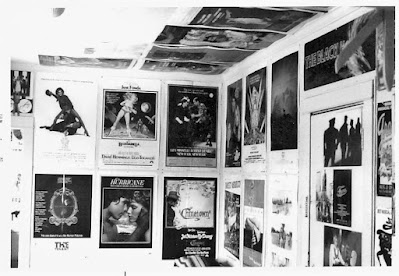

What really boosted my enthusiasm was when I learned that Lipstick was to open in San Francisco at MY theater! Which is to say, the movie theater where I’d been employed since high school--The Alhambra Theater on Polk Street. The once spacious Alhambra had been divided into two smaller theaters in 1974, and Lipstick was slated to replace Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore in Alhambra #1 (after a staggering 13 months!), while Alhambra #2 turned things into an unofficial Chris Sarandon Film Festival by hosting Dog Day Afternoon.

The only downside to this terrific news was my awareness of the Alhambra being a neighborhood movie theater (sister theater to the first-run Regency on Van Ness), and as a result, we rarely ever got the movies that the studios had confidence in.

I’m not sure if the fault lies with the actor, director, or simply how the role was written, but given that the reality for many women is that rapists look like the average guy-next-door, it does the film no favors to have Sarandon's character be a weird, twitchy, Norman Bates type. At our first glimpse of him, he's so obviously off-the-rails that we question Chris' judgment in letting her little sister near him in the first place.

With a dash of trepidation now introduced to my otherwise unbridled sense of anticipation, I was reluctant to see Lipstick in the usual manner of theater ushers…in out-of-sequence bits and pieces while standing in the back of the theater with a flashlight. Craving the full, uninterrupted Lipstick experience, I went on opening night (on my day off) and sat in a sparsely populated, virtually all (gay) male audience. The porno theater vibe of the experience was hard to ignore.

Lipstick had been booked into the Alhambra for a month, but there was no way it could survive four weeks as a solo. After the first week, Lipstick was paired with Straw Dogs (1971), then Chinatown (1974), and finally Once is Not Enough (1975).

I think I went into Lipstick expecting something perhaps along the lines of Klute…a gritty crime story built around a character study of a woman. I was way off. I sat through Lipstick twice that night, liking it more the second time when I surrendered to it being the schlock exploitationer it was. And while it was not the movie I had hoped it would be, it was somehow both better and worse than I could ever have imagined.

And if you think that sentence sounds convoluted and paradoxical, well, say hello to the two words that perhaps best describe Lipstick.

.JPG) |

| Vogue meets International Male |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

As a lifetime devotee of so-bad-they’re-good movies, and confirmed aficionado of Cinema de Strange, virtually everything I love about Lipstick stems from its outré luridness. It's so trashy! It’s like a Sidney Sheldon potboiler crossed with an Italian Giallo. And as Lipstick’s alluring but superficial gloss isn’t offset by anything more substantive in the way of writing, acting, or characters, none of it actually feels tethered to reality. Too much of Lipstick’s rape & revenge plot feels engineered to provide a visceral experience, not a contemplative one.

.JPG) |

| Dressed to Kill |

What can you say about a movie whose apogee and nadir is the blissfully baroque image of a beautiful, statuesque model, lacquered and coiffed, racing through the parking lot of the Pacific Design Center in a glittering red evening gown while brandishing a rifle? It’s got Ken Russell written all over it.

It’s important that I not be too dismissive of Lipstick, for though it was a commercial and critical flop (one critic called it a “Tower of Trash”), Lipstick actually did influence rape laws in California. In late 1976, the California Legislature passed a resolution that prohibited the mention of a rape victim’s sexual history from being brought up in court. It was named The Margaux Hemingway Resolution No. 109 in her honor.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

That Lipstick is a triumph of style is nowhere more evident than in the superb title sequence, which, for me, is alone worth the price of admission. The film’s opening 3 ½ minute model photoshoot economically combines a chic, music video-style credits sequence with the subtle (the first and only time that word can be applied to anything related to this movie) establishment of Lipstick’s undeveloped subthemes regarding the normalized dehumanization at the core of sexism and misogyny.

We see a woman, passive and silent, attended to by a phalanx of men devoted to enhancing her appearance. Often using the language of seduction (tellingly, the only female voice present is dismissed summarily). We're left to ask ourselves. is the woman we’re watching being glorified or objectified?

It's practically documentary: Margaux Hemingway is photographed by the man who launched her modeling career, Francesco Scavullo. Also present are Scavullo's assistant and life partner, Sean Byrnes, Way Bandy (makeup), and Harry King (hair). The only fictional addition is actress Catherine McLeod, playing an ad agency executive.

PERFORMANCES

Though ill-served by a script that conceived her character as almost entirely reactive, I like Margaux Hemingway in Lipstick and never thought she was as bad as the critics made out. True, she doesn’t have much range, but she has an appealing presence and earthiness that might have been showcased to better advantage with a director more protective of her limitations (you don’t keep cutting to reaction shots of someone with so little variance in expression). Still, if you compare Margaux’s performance in this, her first movie to, say, Raquel Welch in her 13th feature film…1969s Flareup (which shares with Lipstick a similar “A woman’s outrage, a woman’s revenge!” dramatic arc), Margaux comes off looking like Liv Ullmann.

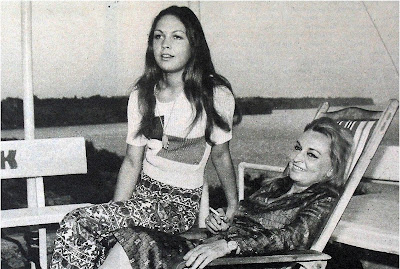

Everything that was said and written about Mariel Hemingway stealing the movie out from under everyone is quite accurate. As the most authentically realized character in the film, her performance is remarkable in its naturalness and sensitivity. When the failure of Lipstick signaled the end of Margaux's lucky streak, the accolades Mariel received created a rift between the sisters. Margaux was quoted as saying: “She ended up stealing the movie and deserved the acclaim, but I was upset. Because it was as if people were tired of me and gave her the attention.”

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

I can't say whether Lipstick is simply a timepiece that stands as evidence of an era when no one batted an eye that a team of men would craft a movie about rape without the creative input of even a single woman, or if it's a movie that deserves credit simply for drawing attention to a topic few major films were even willing to tackle. For me, part of its lingering legacy is the sad, meta intersection of reality and fantasy that comes with the participation of the two Hemingway sisters and all that we now know that we couldn’t have known then.

|

| Cover Girls Cover: An item placed in front of something to protect or conceal |

It's discomfiting to watch a film about rape/sexual abuse that stars siblings who themselves faced issues concerning mental health, body image, eating disorders, alcohol and drug abuse, and sexual abuse.

Margaux Hemingway died of an overdose on July 1, 1996, at the age of 42. Mariel became a successful Oscar-nominated actress (Manhattan - 1979) and is currently a tireless advocate for mental health.

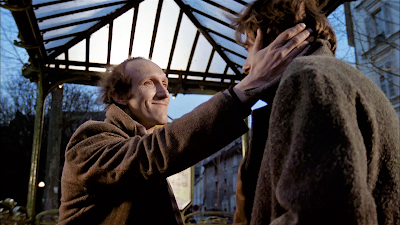

Lipstick co-stars Mariel Hemingway and Chris Sarandon went on to work together in three other films: Road Ends, 1997; Perfume, 2001; and above, a Canadian film adaptation of Louisa May Alcott's Little Men, 1998.

BONUS MATERIAL

Lipstick's fabulous opening sequence.

From Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow Up (1966) to Faye Dunaway stopping traffic in Eyes of Laura Mars (1978), fashion shoots in movies have always been a favorite of mine.

The disco-era vibes are strong in “(You’re) Fabulous Babe” - 1977- a tune written by advertising whiz Bob Larimer to launch Fabergé's BABEfragence line. Sung by recording artist Kenny Williams.

|

| Francesco Scavullo |

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2024

.png)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.png)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)