For me, the history of CHICAGO has always been inextricably linked with that of A Chorus Line. CHICAGO premiered on Broadway on June 3, 1975; A Chorus Line followed six weeks later, on July 25, 1975. CHICAGO opened to mixed reviews and struggled at the boxoffice; A Chorus Line was met with rave reviews, won the Pulitzer Prize, and was nothing short of a cultural phenomenon.

CHICAGO was nominated for 11 Tony Awards, won 0; A Chorus Line was nominated for 12, won 9.

CHICAGO and A Chorus Line also happen to be linked together in my memory. Certainly, I recall that day in August 1975 when I visited The Gramophone, a gay-owned and operated record store on San Francisco's Polk Street, and purchased the Original Broadway Cast Recording LPs of both shows. Although I hadn't yet heard a single note from either score, I was so fired up from consuming all the After Dark Magazine-fed hype surrounding the opening of each production (that invaluable, homoerotic, national entertainment magazine being my sole West Coast pipeline to what was happening on Broadway), that I was almost smug in my confidence that my two blind purchases were far from being a gamble.

|

| August 5, 1975 - $4.88 each Both were single LPs in glossy gatefold jackets loaded with photos & liner notes |

Given that Broadway musicals don't crop up with the regularity of movies, the appearance of the highly anticipated shows was quite a big deal to me. Before CHICAGO & A Chorus Line captured my imagination, the last Broadway cast album I'd purchased was Sondheim's A Little Night Music, a musical meal I'd been dining out on since 1973. Having committed every note and melody of that splendid score to memory by then, I could scarcely believe my good fortune that 1975 held forth the promise of TWO major Broadway musical releases I could submerge myself in.

Back in the day, all the smart money was on CHICAGO. The only familiar names A Chorus Line boasted were composer Marvin Hamlisch, then all but unavoidable after his recent Oscar win for The Sting (1973), and director-choreographer Michael Bennett, whose name was familiar to me from the liner notes of the library-borrowed cast albums of Company and Follies. CHICAGO distinguished itself as the musical with the Broadway heavy hitters and showbiz pedigree. It marked the Broadway musical return of Gwen Verdon (her last Broadway musical was 1966's Sweet Charity)! The professional reunion of husband-and-wife collaborators Verdon & Fosse! The reteaming of Fosse with his Cabaret and Liza with a Z collaborators: the composer-lyricist-writing duo of John Kander and Fred Ebb! And best of all, CHICAGO marked the first-time pairing of two genuine Broadway legends…Gwen Verdon and Chita Rivera!

|

| Illustration by Sam Norkin -1975 |

Wanting to start with the "sure thing," I listened to the CHICAGO album first, which became one of those rarer-than-rare occurrences where one's extraordinarily high expectations are met and exceeded. Hearing that incredible score for the first time...every single song a showstopper...not a clunker in the bunch...was such a thrill. The songs and their often hilarious lyrics set my imagination on fire... I could practically see the entire production in my head. I was instantly attracted to the storyline--the phoniness of show biz reflecting the phoniness of the American legal system.

And if the cynicism at CHICAGO's core struck me as caustic and pessimistic, consider that I was just 17 at the time (sarcasm and snark are like crack cocaine to a teenager) and that it was the summer of '75. The summer that saw the dynamic downer duo of Nashville and The Day of the Locust released to movie theaters just weeks before. The timing couldn't have been more perfect. CHICAGO was simply riding the crest of the zeitgeist.

|

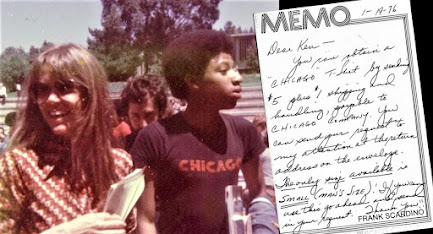

| May 6, 1976 |

That's Jane Fonda speaking at a Tom Hayden rally in Sacramento and 18-year-old me in this, the only photo I have of my beloved official CHICAGO T-shirt I wore for years until it disintegrated. An image captured mere moments before Ms. Fonda graciously signed the Barbarella photo I've got secreted away in the book you see tucked under my arm (The Busby Berkeley Book). The memo is an affirmative reply to my written request to NY's 46th St. Theater inquiring about the possibility of purchasing a CHICAGO T-shirt (mail-order Broadway merchandise was yet to be a thing). It cost a whopping $5 plus $1 shipping.

Next, I listened to A Chorus Line, optimistically resigned to the certainty that it couldn't match my CHICAGO experience. Jump ahead several hours. Me on the floor in front of the family stereo, headphones on, in a theater geek's state of transcendence, eyes red and nose runny from listening to A Chorus Line three times in a row and bawling my eyes out.

And there you have what was then, and continues to be, the essential link in my relationship with CHICAGO and A Chorus Line. They're culturally joined at the hip for me. Iconic templates of a particular time and place in my life: I'd graduated from high school in June, I'd been "out" to myself for about two years (four more years to go for my family), it was the summer of Jaws, and it was the summer of my independence. And these two shows, listened to as regularly and relentlessly as though they were on a loop, were the soundtrack of my adult-adjacent freedom.

|

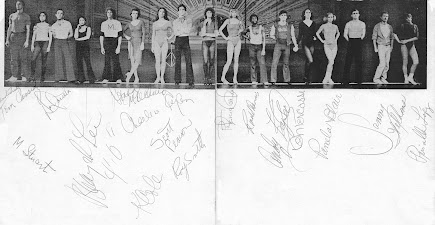

| June 7, 1976 I saw A Chorus Line when the National Company came to San Francisco's Curran Theater in May. Ever the autograph hound, my friend and I became stage-door Johnnies for the show's entire run |

But CHICAGO was always the diamond…sharp, dazzling, and cold, while A Chorus Line was always the heart (a vision of Lauren Bacall singing "Hearts, Not Diamonds" in The Fan just popped into my head). To me, A Chorus Line was a dark, almost melancholy show... a Follies for theater gypsies...but unlike CHICAGO, it was humane and compassionate. And that made listening to it a poignant and exhilarating experience—all goosebumps and waterworks. Each musical, reflecting as they did, opposite yet equally valid faces of our culture (post-Watergate disillusionment & "Me Generation" introspection), also appealed to the contrasting sides of my own nature. CHICAGO and A Chorus Line complemented each other.

It wasn't until 1992 that the opportunity arose for me to actually see a production of CHICAGO on stage for the first time. The Long Beach Civic Light Opera put on a fabulous, faithful-to-the-original production starring Juliet Prowse and Bebe Newerth, utilizing Tony Walton's original set designs, Patricia Zipprodt's costuming, and featuring two members of the original 1975 cast. It was astoundingly good. This may explain why I was never very fond of the pared-down, anachronistically costumed look of CHICAGO's phenomenally successful 1996 Broadway revival. An antipathy reinforced when I saw a 2012 production starring Christie Brinkley (by this point, stunt-casting was the only teeth the show had left).

Since 1975, A Chorus Line's cultural grip has weakened a bit. Thanks to a monumentally mishandled 1985 movie adaptation and the musical's once-innovative confessional format, which feels almost quaint in the modern climate of social media oversharing. Meanwhile, CHICAGO, a show once criticized for its relentlessly downcast gaze into life's sewers, has hung around long enough for its down-in-the-gutter perspective (I hear Candy Darling in Women in Revolt "Too low for the dogs to bite!") to be precisely eye-level with what mainstream American culture has come to normalize, reward, and elect.

And something happened that, for the longest time, I had given hope of ever seeing...after decades of false starts and empty rumors (Liza and Goldie! Goldie and Madonna!), and against impossible odds (non-animated movie musicals were given the death knell) CHICAGO, at last, had been made into a movie. Twenty-seven years after its Broadway debut.

.jpg) |

| Renee Zellweger as Roxie Hart |

.png) |

| Catherine Zeta-Jones as Velma Kelly |

.jpg) |

| Richard Gere as Billy Flynn |

.jpg) |

| Queen Latifah as Matron Mama Morton |

|

| John C. Reilly as Amos Hart |

CHICAGO, the Bob Fosse/Fred Ebb/John Kander musical vaudeville about two amoral, overaged, gin-soaked jazz babies on murderers' row, desperate to parlay their 15 minutes of criminal infamy into showbiz careers, was made into a $45 million major motion picture. Who was the director tasked with reviving the viability of live-action musicals? None other than Rob Marshall, the Tony Award-nominated choreographer-director of that 1992 Juliet Prowse/Bebe Neuwirth Long Beach production that knocked my socks off.

It's impossible to overstate how excited I was that Friday morning in December of 2002 when my partner and I, returning home from a Christmas trip, stopped off at our place just long enough to drop off our luggage so we could hightail it to Century City and be among the first audience to see CHICAGO on its December 27th opening day in LA. When the film was over and we were handed our evaluation cards by anxious-looking marketing people (the film wouldn't open wide until January), I thought I had died and gone to stage-to-screen heaven. We were both so euphoric over what we'd just seen, and after exiting the theater, we swiftly got right back in line to see it again.

|

| Chita Rivera as Nickie Broadway's original Velma Kelly makes a cameo appearance as a Cook County Jail inmate. Her name is a nod to the character she played in Fosse's 1969 film Sweet Charity. |

Rob Marshall and screenwriter Bill Condon avoided several pitfalls from the outset by not trying to reimagine the show for the screen. Instead, they came up with a device (the musical numbers erupt out of Roxie's fevered fantasies) that made the highly stylized, stage-bound show more cinematic. Boasting spectacular cinematography, a sensational cast, and dazzling choreography, they succeeded in bringing the CHICAGO I loved to the screen. (It had been my gravest fear that the "Victoria's Secret meets International Male" Broadway revival version of CHICAGO would be the only surviving template for future generations.)

The film became a major boxoffice and critical hit, garnering a whopping 13 Oscar nominations that year, winning 6, among them Best Picture. CHICAGO revitalized the movie musical.

|

| Taye Diggs as The Bandleader |

|

| Christine Baranski as Mary Sunshine |

But writing this now, in 2022, it's clear my once all-encompassing ardor for CHICAGO has cooled a bit over the years. After the dust of anticipation settled and I was able to breathe a sigh of relief that the screen adaptation wasn't a botch job like A Chorus Line: The Movie, only then did I notice that somewhere along its 27-year path to the screen, CHICAGO had become neutered.

When I look at CHICAGO today, the film's black comedy subtext targeting the institutional corruption of the media, penal system, politics, and law, doesn't hit nearly as hard as how sympathetically Roxie and Velma are portrayed.

Gwen Verdon & Chita Rivera gave us a Roxie and Velma who were genuinely "...older than I ever intended to be." The undeserving pair's hunger for vaudeville fame was a last-gasp act of desperation and resentment after a lifetime of failure and rejection. The Roxie and Velma of the film are both so young and beautiful (and talented) that we're left with the impression that life, indeed, has been unduly dismissive of them. Each suffers so many humiliations, setbacks, and exploitations that by the finale, we're rooting for them and have forgotten (or stopped caring) that they are remorseless murderers. This is obviously the whole point, and the film stays true to that notion... academically. But rather than leaving the audience with a bad taste in its mouth for its complicity in the amorality, I know I was just happy to see these two exploited sad sacks seeing their dreams come true. It was a feel-good ending masquerading as hard-knock cynicism.

Fosse/Verdon (2019)

|

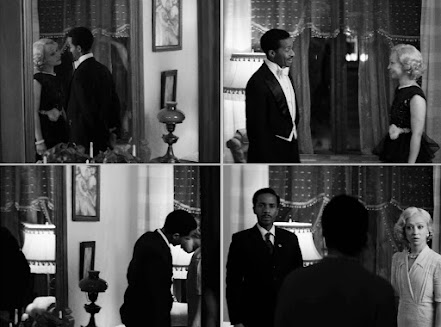

| Bianca Marroquin and Michelle Williams |

CHICAGO rehearsals 1975

Bob Fosse: "And I'm saying that it would be better for the show if the…."

Gwen Verdon: "Better for the show? Oh, really? Better for the show… Is that really what you think? I'll tell you what would have been better for the show: opening four months ago with a director who wasn't hellbent on turning it into two hours of misery for the audience."

The above exchange, although fictional (from the splendid miniseries Fosse/Verdon), reflects a genuine issue that plagued the original production of CHICAGO from the start: concern that Fosse had made the show too bitter and misanthropic for its own good.

Hollywood had no such concerns. When the time came for the film adaptation, far too much Hollywood money was riding on CHICAGO for the studio to even consider taking a chance on having another Pennies from Heaven on its hands (1981's mega-depressing megaflop about another amoral character who uses musical fantasy to escape reality). Miramax insured its $45 million investment by making sure that with this CHICAGO, a good time was going to be had by all. Even if it was a musical about murder, greed, corruption, violence, exploitation, adultery, and treachery--all those things we all hold near and dear to our hearts.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS MOVIE

No one can say Rob Marshall didn't understand the assignment. He was hired to deliver a hit movie musical, and he did. Brilliantly. It really wasn't his fault that the CHICAGO he (and I) fell in love with back in 1975—labeled by many critics at the time as mean-spirited and ugly—had long given way to the forget your troubles, c'mon get happy crowd-pleaser CHICAGO of today. The revamped 1996 Broadway revival of CHICAGO turned Fosse's 1975 ambivalent success into the 2nd longest-running musical in Broadway history. And it didn't accomplish that by making visiting tourists and blue-haired theater parties uncomfortable. It became a hit by submerging the show's unsavory attributes under layers of glamour, sex, and style. Yes, with nary a trace of irony or self-awareness, CHICAGO had become Fosse's "Razzle Dazzle" number.

CHICAGO's themes remain relevant, but its contemptuous

view of America and humanity no longer discomfit

PERFORMANCES

Casting a movie in a way that invites comparisons to a show's original cast can be problematic. Since there IS no other Roxie Hart for me but Gwen Verdon, I was actually pleased that the film went with an entirely different take on the character. I hadn't seen Renée Zellweger in anything before, but her Roxie has a Glenda Farrell quality—tough, quirky, wisecracking—that feels both period-perfect and suits the film's concept. Catherine Zeta-Jones is dynamic as Velma Kelly, but the lovely woman hasn't a coarse bone in her body. The "foul-mouthed broad" part of her performance never convinced me. It's impossible to take your eyes off of her when she's onscreen, but when she tries for Velma's lowbrow vulgarity, the best you get (and here she isn't alone) is Damon Runyon-esque posturing of the Guys and Dolls sort. The entire cast of CHICAGO is exceptionally good, Richard Gere--the most animated I've seen him onscreen since Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977)--being a particular delight, displaying even more playful showmanship at age 52 than in that online clip of his 1973 appearance in Grease.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

The thrill and terror of seeing any movie adaptation of a favorite show is discovering what they did with (or to) the songs you loved best. Sometimes your favorites don't even make it into the finished film (On a Clear Day You Can See Forever's baffling decision to excise its sole lively production number, "Wait Till We're Sixty-Five"). Other times, you'll wish they hadn't (don't get me started on A Chorus Line: The Movie again). From the very first time I listened to the CHICAGO Broadway cast album, "Funny Honey," "The Cell Block Tango," "Roxie," and "Nowadays" became my favorite songs in the show. How did their transfer to film rate?

.jpg) |

| "Funny Honey"- B |

The movie goes for a sultry, torchy interpretation of this number and scores high points for how it cleverly establishes the film's visual vocabulary for Roxie's fantasies. It only earns a "B" grade because, as good as Zellweger is, she simply cannot match Gwen Verdon's comedic delivery. An observation that's less a jab at Ms. Z than a tip of the hat to Verdon.

|

| "The Cell Block Tango"- A+ |

Every detail about this inspired fever dream of a number works magnificently for me. I especially love that Marshall includes the "victims" in this death tango, and the way the prison reality is intercut with the fantasy. The number is theatrical, it's cinematic, it's a scarlet wall of women behind bars. My favorite number in the movie.

Of course, it's not hard to see where The Cellblock Tango owes a nod to The Jailhouse Rock

(Image from the 1969 Elvis Presley Album Cover)

|

| "Roxie"- A+ |

Roxie is a singular sensation to herself in this narcissist's anthem that becomes a terrifically glossy and stylish production number in the style of the classic Hollywood musicals. It's deliciously old-fashioned, and Zellewgger shines in it. Literally.

|

| "Nowadays/Hot Honey Rag"- A+ |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

In spite of that dreadful, written-for-the-film, Oscar-bait song "I Move On," I'll always enjoy the movie version of CHICAGO. It's an incredibly well-crafted musical that I credit for rescuing the genre from animated singing teapots, and I genuinely think it deserves all of its success. (Though Marshall revealing in the DVD commentary that personal fave-rave Toni Collette was almost cast as Roxie was a bit of "what if?" news I didn't need. OMG...can you imagine?! Be still, my heart.)

But through no fault of its own — after all, the movie didn't change, I did — CHICAGO just doesn't stand the test of time for me as what I might consider a classic musical. When I revisit Cabaret (1972), even after all these years, it's a film that continues to offer me a full-course meal. Rewatching CHICAGO recently was like having a sorbet dessert...thoroughly delightful and pleasant, but there wasn't anything for me to chew on.

I told you that CHICAGO and A Chorus Line are eternally linked for me. Here it is 2022; both shows have been made into films, yet when I really want to have my best experience of either and both...I still go back to listen to those original Broadway cast records I purchased in August of 1975.

BONUS MATERIAL

There's a wealth of material about CHICAGO on YouTube and throughout the internet. You can see clips from the original production, the 1992 Long Beach production, the 1996 Broadway revival, and the deleted "Class" musical number from the motion picture. Any footage you can catch of Gwen Verdon and Chita Rivers performing is guaranteed to be pure magic.

|

| Also available on YouTube (for the time being) is the silent film version of Chicago (1927) and the Ginger Rogers remake/reworking of Roxie Hart (1942) - Thanks, Cinefilia |

My favorite curio is an audio track from the 1975 Philadelphia tryouts that features cut songs and the original lyrics to "The Cell Block Tango" (wherein we discover "Lipschitz" initially referred to Jacques Lipschitz, the cubist sculptor). Listen to it HERE.

|

| "Minsky's Chorus" by Reginald Marsh - 1935 The painting that inspired the original CHICAGO poster art |

Clip from "The Cell Block Tango"

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2022

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.png)

.JPG)