Stephen Sondheim

March 22, 1930 - November 26, 2021

Countless obituaries, tributes, eulogies, and “In Memoriam” articles reiterated the indisputable fact that the death of Broadway legend Stephen Sondheim signaled the end of an era in American Musical Theater. And indeed, the breadth of his impact is difficult to overstate. Stephen Sondheim almost single-handedly changed the look, sound, and content of the American musical. Transforming the popular medium that once strove for nothing deeper than “pleasing the tired businessman” (i.e., to amuse and entertain, not instruct or strain the brain) into a sophisticated and challenging art form illuminating complex societal themes and exploring the darker corners of the human condition. It’s impossible to imagine the likes of his particular genius will ever be seen again.

|

| Sonheim in 1973 |

But to me…a gay man who discovered this brilliant composer-lyricist during my floundering adolescence in the Sexual Revolution/Gay Liberation ‘70s, it’s hard not to look upon the obvious tragedy of Stephen Sondheim’s death at age 91 as simultaneously representing a kind of triumph. A triumph of survival, a triumph of the indomitability of the creative voice, and certainly a triumph of a queer artist's personal journey (from being closeted, coming out in his 40s, to [shades of "Marry Me a Little"] getting wed at the age of 87) in a nearly 70-year career.

|

| Sondheim and husband Jeff Romley - Wed in 2017 |

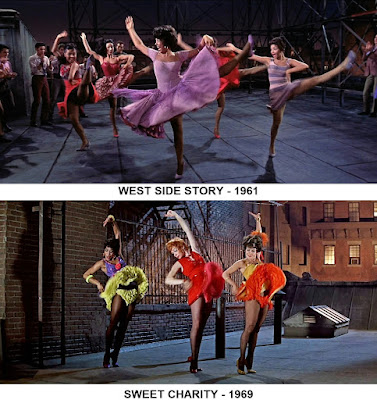

For what’s not triumphant in being a gay man surviving the devastation of the AIDS plague of the ‘80s and living to the astoundingly ripe old age of 91? It’s certainly a triumph that the trajectory of Sondheim’s long career dramatizes the struggle of the American LGBTQ experience: Sondheim’s first Broadway show (1957s West Side Story) was the creation of no less than FOUR societally-mandated closeted gay and bisexual men. By the time of his death, Sondheim was an out-and-proud, world-renowned public figure legally wed to his husband of four years.

|

| Sondheim with the cast of the movie version of Into the Woods |

As one of Broadway’s most lauded composer-lyricists (8 Tony Award wins - including an Honorary Lifetime Achievement in Theater Award, 8 Grammys, a Pulitzer Prize, a Presidential Medal of Freedom, and more) Hollywood beckoned Sondheim from the start. And of his 18 theatrical productions, six have made it to the screen to date. The work he created specifically for the movies includes composing a score for French director Alain Resnais, writing original songs for several feature films (one even garnering him an Oscar win), and collaborating on the screenplay of a murder mystery with his friend and rumored lover Anthony Perkins.

The relative or comparative success/failure of Hollywood’s adaptations of Sondheim’s work has sparked much unnecessary debate over the years. In the end, it's Sondheim himself who comes across as the level-headed mediator, what with his understanding of the differences between the mediums of film and theater, and therefore being considerably less bent out of shape than his acolytes by the often necessary compromises required in bringing his theatrical works to the screen.

I think evidence of Sondheim's easygoing philosophy can be found in his music.

One of the more consistent themes running through Sondheim's work is that, while idealism is both an elemental and essential part of being an artist, a lover, a character in a fairy tale, a dreamer, a suburban married couple, or even a sociopathic killer; the achievement of perfection itself is something unattainable. There can never be such a thing as perfection or "happily ever after" where human beings...in all their flawed complexity...are involved.

So many of his musicals end with characters thinking they are “settling” for the less-than-perfect when the overarching theme stresses that once one abandons illusion and fantasy (which makes us question whether we're happy "enough" or if our happiness is the "right kind"), it opens us up to realizing that in most instances, true happiness is never ideal, and that it rarely ever looks the way we expect it to. More often than not, when discovered, it's found in the only place it can ever truly be: in the here and now, wherever that may be, and whatever that may look like. Accepting who we are, what we have, and finding that there is both happiness and contentment within the imperfect, is, I think, the key to happiness and what it means to grow up.

- "In The Movies" - from Sondheim's first musical Saturday Night - 1955 (unproduced until 1997)

“In the Movies” is a comic musical number calling attention to the discrepancy between life as we know it and life as depicted on the big screen. In the end, the song makes the case that wishing for reality to be more like the movies is an exercise in futility when it’s precisely life’s deficiencies that make movies so pleasurable (and necessary!). Better to relax, sit back, and enjoy these idealized fantasies for what they are. Why dwell on the unhappy thought that life is so seldom as magical as the movies when the greatest gift that movies offer us is the magic of fantasy? Why not just sit back and “settle for the dream”?

That repeated lyric, with its echoing of the Sondheimian ethos of accepting things as they are…accepting the things you cannot change, feels just right for the title of my brief look at the uneven cinema legacy of the man who became the face of American Musical Theater.

|

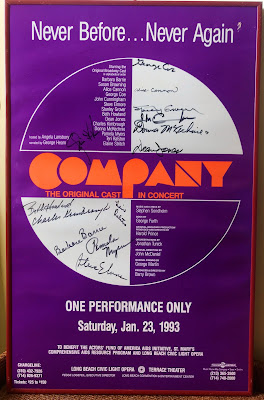

| In 1971 I fell in love with the OBC album of Sondheim's Company (1970). In 1993 got to see the original cast perform it in concert. |

I suspect theater fans will always prefer their Sondheim onstage and lament that his film adaptations inevitably fall short. And I can see their point. Live theater presents the uncompromised vision and is different each time you see it. But live theater is not as available to some as it is to others. Certainly not as available as film.

I'm a movie guy and a Sondheim fan to boot, so my attitude is that while I would love it if every screen adaptation of a Sondheim show was "perfection," there is no such thing. And certainly, when it comes to film, what's done is done. There's no matinee the following day where problems can be fixed.

In any discussion on the topic of whether the movies have ever done justice to the work of Stephen Sondheim, my answer would be a qualified no. But instead of blocking my blessings by playing "It Would Have Been Wonderful," how much better it is for me to sit back and simply appreciate the rare gift it is to have any of Stephen Sondheim's genius preserved on the screen at all. It's a dream I'm more than happy to settle for.

|

| WEST SIDE STORY - 1961 |

|

| GYPSY - 1962 |

Directed by Mervyn Leroy and adapted from the 1959 Ethel Merman Broadway musical. Hitting two for two, Sondheim’s second Broadway hit (this time supplying the lyrics to Jules Stein’s music) became his second movie adaptation and second collaboration with Natalie Wood. Controversially cast in place of the bombastic Merman, the vocally-manipulated Rosalind Russell. A delightful, relatively faithful adaptation, Gypsy is another film I’ve exhaustively covered in an earlier post (hint: I’m crazy about it), my only gripe being that it cuts one of my favorite songs, “Together Wherever We Go.”

|

| A FUNNY THING HAPPENED ON THE WAY TO THE FORUM - 1966 |

|

| THE LAST OF SHEILA - 1973 |

Directed by Herbert Ross from an original screenplay by Stephen Sondheim and actor Anthony Perkins. Sondheim combined his passion for puzzles and games with his early experience writing for television in the ‘50s (he wrote several episodes of the comedy program Topper) and came up with a doozy of an all-star whodunit set on the French Riviera. The Agatha Christie-style plot is as complex and twisty as any Sondheim melody, and it’s easy to imagine Perkins contributing a great deal to the gossipy, insider feel of the film's movie-industry setting and its cast of unsympathetic opportunists. The Last of Sheila is another film I’ve written about in a previous post…and by now you know the drill. I’m crazy about it.

|

| STAVISKY - 1974 |

Directed by Alain Resnais (Last Year at Marienbad). Sondheim was approached by Resnais (who professed to be a fan of the composer) to write the period score for this stylish crime noir set in the early ‘30s and based on the life of real-life political swindler, Serge Alexandre Stavisky. Resnais’ film is an Art Deco visual feast to which Sondheim contributes a breathtakingly lush, sweepingly romantic score. Even if you never have the opportunity to see the sumptuous motion picture, you owe it to yourself to get your hands on the soundtrack. The music is beyond exquisite.

|

| THE SEVEN-PER-CENT SOLUTION - 1976 |

|

| A LITTLE NIGHT MUSIC - 1977 |

|

| REDS - 1981 |

|

| DICK TRACY - 1990 |

|

| THE BIRDCAGE - 1996 |

|

| SWEENEY TODD: THE DEMON BARBER OF FLEET STREET - 2007 |

|

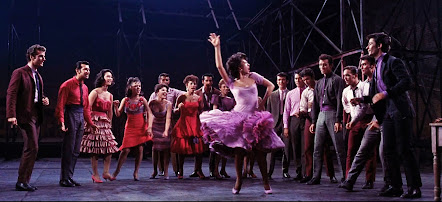

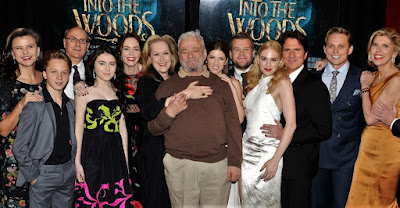

| INTO THE WOODS - 2014 |

Directed by Rob Marshall and adapted from the three-time 1987 Tony Award-winning Broadway musical. Remarkably, this film version of Sondheim’s grim adult take on Grimm’s fairy tales marks my first time ever seeing Into The Woods (1984’s Sunday in the Park with George had put me off Sondheim for a bit), so I’m willing to accept the tiresomely patronizing assurances from my theater-geek friends that until I watch the complete production performed by the original Broadway cast for cable TV in 1991, I STILL haven’t seen Into the Woods. Be that as it may, in the spirit of discovery, I must say I had the best time watching Marshall's film. Wonderful performances throughout, and that absolutely superb and complex score. Subsequent revisits…with fast-forward remote at the ready… have been less ecstatic. The film was nominated for 3 Oscars.

|

| CAMP - 2003 |

|

| WEST SIDE STORY - 2021 |

|

| TICK, TICK...BOOM! - 2021 |

I honestly tried, but I found it impossible to make it through even the first 20 minutes of 2021's Tick, Tick...Boom!, so I missed out on experiencing Sondheim's audio-only "cameo" (as himself) in dramatic context (I watched a clip of the scene on YouTube). In a mini-monologue written by Sondheim himself, his voice is heard on an answering machine giving up-and-coming composer Jonathan Larson (Andrew Garfield) a timely pep talk. The film, set in 1999 gives us Stephen Sondheim in the flesh, portrayed by actor Bradley Whitford of Get Out (2017). My personal feelings about the movie aside, I can't imagine a greater testament to Stephen Sondheim's enduring brilliance than his being depicted in this film as an icon of musical theater, a patron saint and inspiration to young artists.

GLASS ONION - 2022

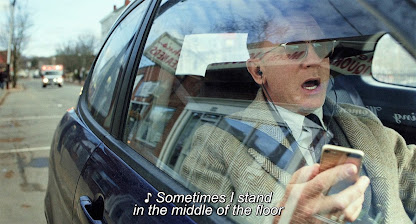

"Sorry, Blanc. You're thrown out of the airlock. It's a no-brainer." - Those are the only lines spoken by Stephen Sondheim in this, his last screen appearance. Playing himself, he appears in a COVID lockdown Zoom gathering with Broadway legend Angela Lansbury (also her final screen appearance), NBA All-Star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and actress Natasha Lyonne. They are all playing the online video sleuthing game "Among Us" with world-famous fictional detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) in this, his second screen mystery (following the character's debut in Knives Out - 2019). Sondheim's appearance as gamer "Steve S." is but a cameo, but in context, it's an ideal screen sendoff for one of popular culture's most well-known game-players. A screen farewell made all the more satisfying because Benoit Blanc's fondness for Sondheim music was wittily referenced in Knives Out, and because Rian Johnson's murder mystery Glass Onion consistently pays loving homage to Sondheim & Perkins' twisty & bitchy 1973 whodunit The Last of Sheila.

*****

Stephen Sondheim's legacy for me is indelible and rich. For some reason, he seems to have been the perfect composer to introduce me to musical theater at an impressionable age. He set a very high standard. That his reputation continues to grow and his work is recognized and lauded by an entirely new generation makes me glad that at least a few of his shows have been preserved on film.

|

| My Favorite Stephen Sondheim Musical Scores |

My Top Five Favorite Sondheim Songs:

"Every Day a Little Death"

"Not While I'm Around"

"Losing My Mind"

"There's Always a Woman"

"Side by Side by Side/What Would We Do Without You?"

Readers: No one should have to pick a "favorite" from Sondheim's sizeable catalog of impossibly beautiful (and riotously funny) songs, but if you care to share a particular Sondheim composition you enjoy or that means something to you, I'd be interested to know.

BONUS MATERIAL:

Liza Minnelli sings Sondheim's "Losing My Mind" - from her Results album -1989

I know a music video doesn’t officially fit the “Sondheim in the Movies” theme of this tribute, but this is included here because Oscar-winning, Miss Show-Biz herself, Liza Minnelli, delivers more deliriously extravagant drama, anguish, camp, and genuine pathos in 4 ½ minutes than you’ll find in a Douglas Sirk/David Lynch film festival.

For those desperate to make a movie connection; imagine this video as a 20-years-later short film sequel to Minnelli's The Sterile Cuckoo (1969) with an adult Pookie Adams still getting herself into obsessive, one-way relationships.

Pet Shop Boys (Neil Tennant, Chris Lowe) produced this infectious synthpop dance version of Sondheim’s torch ballad from Follies. On the strength of Minnelli’s committed, full-throttle performance, I also find this majestically melodramatic music video…which even features a nod to the Emcee in Cabaret…to be delicately moving. Directed by Briant Grant.

|

| In the comic whodunit Knives Out (2019), Daniel Craig plays a gay master detective with a fondness for Sondheim |