Although Myra Breckinridge was a movie that thoroughly captured my adolescent imagination and attention in 1970, it was also one of the few films my parents absolutely forbade me to see. My folks were usually obligingly (and conveniently) in the dark about the many age-inappropriate matinees I traipsed off to on Saturday afternoons, but Myra Breckinridge proved an inopportune exception. Behind it all was the fact that my parents owned a hardback copy of Gore Vidal's satirical novel (which my sisters and I snuck clandestinely, barely comprehending, peeks at). Thus, they weren't about to let their Catholic School-attending, 12-year-old son see a movie whose much-touted set-piece and raison d’être was the strap-on rape of a young man by a transgender woman in a star-spangled bikini. Good parenting will out!

Needless to say, all of this failed to quell my fascination with the film. On the contrary, it fueled it. The hype surrounding Myra Breckinridge (the words"disgusting" and "obscene" almost always in attendance) set my hormonal teenage mind racing at the thought of Hollywood making the first big-budget, all-star, dirty movie. And here I was, a young man fancying himself a mature-beyond-his-years cineaste, present at what looked to be a seminal moment in the cultural shift in American motion pictures...and I wasn't allowed to participate in it. Life can be so unfair.

|

| "It's going to be treated importantly. It's not going to be dismissed." A sweetly delusional Welch speaking about Myra Breckinridge on The Dick Cavett Show |

Well, as we all know, once Myra Breckinridge hit the theaters, that anticipated cultural shift turned out instead to be but a brief detour into a blind alley. Myra Breckinridge tanked stupendously at the boxoffice, taking with it, Mae West's unasked-for comeback, Raquel Welch's already tenuous legitimacy, and director Michael Sarne's entire career (every cloud has a silver lining). Following months and months of pre-release hoopla, Myra Breckinridge swiftly dropped out of sight, and by the time I finally got around to seeing it, I was 21 years old. It was showing on a double bill with Beyond the Valley of the Dolls at the Tiffany Theater in Los Angeles (a Sunset Strip revival house just blocks away from the site of that iconic rotating cowgirl billboard).

|

| The Sahara Hotel billboard on Sunset Blvd with the iconic rotating showgirl atop a silver dollar. The billboard was erected (if I can use that word in a Myra Breckinridge post) in 1957 and, at one time, included a pool and bathing beauties. It remained in that spot until 1966. The billboard became a landmark, showing up in films like William Castle's The Night Walker - 1964 (bottom) and the Joanne Woodward movie The Stripper - 1963 (top) as a kind of visual shorthand for Hollywood's artifice and merchandising of sex. |

|

| The billboard was recreated for the film. Myra, the symbol of the new woman. |

Obscene and disgusting are certainly in the eye of the beholder, but it's my guess that this sexual revolution comedy was a good deal more shocking at the start of the sexual revolution than during its last gasps. I saw Myra Breckinridge in 1978, and by then, the New Hollywood was on the verge of obsolescence, the underground films of John Waters and Andy Warhol had practically gone mainstream, disco was on the wane, Linda Lovelace had found religion, and The Rocky Horror Picture Show was the latest word in gender-bending camp. In this atmosphere, Myra Breckinridge's legendary irreverence seemed almost quaint. With nothing to be shocked about in its content, all that was left to respond to was the freakshow spectacle of movie stars--who should have known better---making absolute fools of themselves. This may not sound like much, but in the days before reality television, celebrities humiliating themselves was a rarity, not a nightly prime-time attraction.

If you don’t count a thoroughly delightful episode of Mr. Ed (!) in 1965, Myra Breckinridge was Mae West’s first time in front of the cameras since 1943’s The Heat’s On. Top-billed and paid more than twice Raquel Welch's salary, West insisted on singing several songs in the film, although it really made no logical sense for her character, who was a talent agent, of all things. But nobody went to Myra Breckinridge looking for sense.

Much like when a little kid learns his first words of profanity and proudly struts about shouting "Fuck...fuck...fuck...," with no comprehension of what he is really saying; Myra Breckinridge's so-called sexual effrontery is peculiarly naive, and thus, uproariously funny...but in almost none of the ways intended.

Behind Myra Breckinridge's convoluted fantasy about a homosexual movie buff (a typecast Rex Reed) transitioning to become the Amazonian Myra Breckinridge (Welch) in order to destroy masculinity and thus realign the sexes (!?!), there lurks a rather cynical and misanthropic film devoid of subversive convictions, sexual or otherwise, beyond doing anything it can to attract a young audience. At this time 20th Century Fox was so keenly feeling the sting of mega-flops Star!, Doctor Dolittle, and Hello Dolly!, they would have released a widescreen epic about aluminum siding installation techniques if they thought it would be a hit.

Myra Breckinridge is beautifully shot, and splendidly costumed, and I really thought the use of old movie clips was quite inspired; but the casting, script, and performances are downright surreal. I couldn't wrap my mind around this being a film a major studio actually thought audiences would turn out to see. Even by the screwy standards of '70s gonzo cinema (see: Angel, Angel Down We Go) Myra Breckinridge is bizarre beyond belief.

If you don’t count a thoroughly delightful episode of Mr. Ed (!) in 1965, Myra Breckinridge was Mae West’s first time in front of the cameras since 1943’s The Heat’s On. Top-billed and paid more than twice Raquel Welch's salary, West insisted on singing several songs in the film, although it really made no logical sense for her character, who was a talent agent, of all things. But nobody went to Myra Breckinridge looking for sense.

Much like when a little kid learns his first words of profanity and proudly struts about shouting "Fuck...fuck...fuck...," with no comprehension of what he is really saying; Myra Breckinridge's so-called sexual effrontery is peculiarly naive, and thus, uproariously funny...but in almost none of the ways intended.

Behind Myra Breckinridge's convoluted fantasy about a homosexual movie buff (a typecast Rex Reed) transitioning to become the Amazonian Myra Breckinridge (Welch) in order to destroy masculinity and thus realign the sexes (!?!), there lurks a rather cynical and misanthropic film devoid of subversive convictions, sexual or otherwise, beyond doing anything it can to attract a young audience. At this time 20th Century Fox was so keenly feeling the sting of mega-flops Star!, Doctor Dolittle, and Hello Dolly!, they would have released a widescreen epic about aluminum siding installation techniques if they thought it would be a hit.

Myra Breckinridge is beautifully shot, and splendidly costumed, and I really thought the use of old movie clips was quite inspired; but the casting, script, and performances are downright surreal. I couldn't wrap my mind around this being a film a major studio actually thought audiences would turn out to see. Even by the screwy standards of '70s gonzo cinema (see: Angel, Angel Down We Go) Myra Breckinridge is bizarre beyond belief.

|

| Raquel Welch as Myra Breckinridge |

|

| Mae West as Leticia Van Allen |

|

| John Huston as Buck Loner |

|

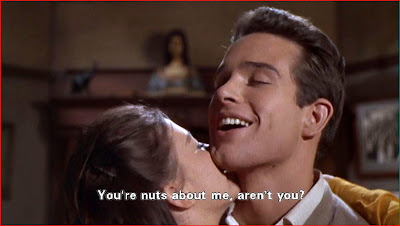

| Roger Herren as Rusty Godowski |

|

| Farrah Fawcett as Mary Ann Pringle |

.JPG) |

| Introducing Rex Reed as Myron Breckinridge |

I'm reminded of the 1955 Frank Tashlin comedy, The Girl Can't Help It, a movie that appears on the surface to be a celebration of rock & roll but is actually a scathingly satiric, anti-rock & roll diatribe. Myra Breckinridge sets itself up as a contemporary sex comedy out to skewer America's sexual hypocrisy and lampoon Hollywood's repressed gender images; but at its core, it's a staunchly anti-sex film, borderline homophobic, and deeply embarrassed by itself. A sexual fake-out promising a more progressive experience than it's capable of delivering.

|

| Something is definitely wrong with an X-rated film that puts Raquel Welch and Farrah Fawcett together in the same bed and doesn't know what to do with them. |

Starting with the bait-and-switch casting of Ms.Welch herself (what else but a perverse sadistic streak would inspire the casting of '60s sex symbol Raquel Welch in an X-rated movie, only to have her be one of the most overdressed members of the cast?), the people behind Myra Breckinridge not only appear to have had little to no understanding of the book, but seem to have harbored an outright contempt both for its subject matter and the young audience whose favor it hoped to curry. Every frame has the feel of 20th Century Fox communicating its resentful vexation at having to stoop so low in order to appeal to the base sensibilities of the suddenly indispensable youth market that kept American movie box offices in a stranglehold during the '60s and '70s.

|

| It's not for lack of bread, like The Grateful Dead Michael Sarne (l.) played a director on the set of Myra Breckinridge. Donald Sutherland (r.) who had a small role in Sarne's first film, Joanna, played a Michael Sarne-esque director in 1970s Alex in Wonderland. Listen to Michael Sarne's 1964 pop hit, "Come Outside" HERE |

Alfred Hitchcock and Cecil B. DeMille may have worn a suit and tie while directing, but by 1970, long hair and a beard were considered standard equipment if you wanted to be taken seriously in Hollywood. Michael Sarne was a former British pop star with only one other film to his credit (Joanna, a film I actually liked) before being handed the $5 million reins to a movie at one time pitched to talents as diverse as Bud Yorkin (Start the Revolution Without Me) and George Cukor. Michael Sarne has continued to work as an actor, appearing in a small role in 2012's Les Miserables, but the debacle of Myra Breckinridge effectively ended his career as a director of any note.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT

THIS FILM

The only people I know disappointed in seeing Myra Breckinridge for the first time are

those expecting it to live up to its notorious reputation. Always a very tame “X”,

Myra Breckinridge is nowhere near as explicit as its rating would suggest, ideologically

dated, more asexual than sexy, narratively jumbled, not particularly funny, and

arrives at its cult appeal mostly by way of having its laid-on-with-a-trowel attempts

at intentional camp land with a resounding thud.

So what does work about the film? To enjoy Myra Breckinridge, one has to accept that its greatest value is as sociological artifact. In the staunchly conventional world of moviemaking, Myra Breckinridge is an oddity that could not have been made at any other time in the history of motion pictures...not even today. Its weirdness is almost exhilarating. You may not get it, hell, you may not even enjoy it that much, but to watch this film is to gaze into the very heart of the panic, chaos, and desperation that was Hollywood in the transitional sixties and seventies. With cinema icons John Huston and Mae West relegated to the roles of dirty-old man / dirty old woman; sexpot Raquel Welch used as the uncomprehending butt of the film’s sole sex joke; and a glossy, $5 million production built around pissing on the entirety of motion picture history, Myra Breckinridge is a big monster truck rally face-off between Old Hollywood and New Hollywood.

PERFORMANCES

No actor gets to choose the role for which they will always

be associated and remembered. Sometimes, as in the case of Mia Farrow and Rosemary’s Baby, it occurs at the start

of a career and establishes a difficult-to-live-up-to standard. When the fates are not kind, it can happen

mid-career with the taking on of an embarrassing role that unjustly overshadows all the quality work that

came before (think Faye Dunaway and Mommie Dearest). Raquel Welch, a breathtakingly

beautiful actress whose career...if one were to base such speculations on talent alone...could

well have gone the way of Edy Williams, has in Myra Breckinridge—for better or worse—one of the best roles of her career. Certainly, it's a role that offered something of a challenge for the actress after a long string of "decorative starlet" leads and walk-ons.

And that is by no means a put-down. While I think the filmmakers cruelly exploit Ms.Welch’s limited range and artificial appeal to create a campy portrait of an affected woman whose image, behavior, and speech patterns are inspired by old movies, Welch is nonetheless surprisingly good. In fact, she’s rather winningly committed to the silliness of it all and shows more life and spirit in the role than she usually does onscreen. She is the only reason the film remains so watchable for me after all these years. Displaying a kind of amateurish aplomb in the face of truly cringe-inducing scenes, Welch is both vivacious and engaging while never coming across as quite human...which, oddly enough, works perfectly for this movie. I still think she gives her best screen performance in The Wild Party (1975), but much in the way I could never envision anyone but Jane Fonda as Barbarella, Raquel IS, and always will be Myra Breckinridge for me, and I applaud her in the role.

And that is by no means a put-down. While I think the filmmakers cruelly exploit Ms.Welch’s limited range and artificial appeal to create a campy portrait of an affected woman whose image, behavior, and speech patterns are inspired by old movies, Welch is nonetheless surprisingly good. In fact, she’s rather winningly committed to the silliness of it all and shows more life and spirit in the role than she usually does onscreen. She is the only reason the film remains so watchable for me after all these years. Displaying a kind of amateurish aplomb in the face of truly cringe-inducing scenes, Welch is both vivacious and engaging while never coming across as quite human...which, oddly enough, works perfectly for this movie. I still think she gives her best screen performance in The Wild Party (1975), but much in the way I could never envision anyone but Jane Fonda as Barbarella, Raquel IS, and always will be Myra Breckinridge for me, and I applaud her in the role.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Two things: Myra's wardrobe, and Raquel Welch's looks. The late, great costume designer Theadora Van Runkle (Bonnie & Clyde, New York, New York) channels her inner drag queen and comes up with some outrageously outré '40s-inspired fashions for America's most famous trans woman. Welch, who has gone on record as saying that her costumes are the only happy memories she takes from the making of the film, is a solid knockout in the looks department, and for all the weirdness she's engaged in, she's probably never been photographed more flatteringly.

Raquel Welch was 28 when she starred in Myra Breckinridge, and in 2016, she'll be exactly the same as co-star Mae West's age when they clashed so famously during the film's production (West was 76). With those kinds of statistics, small wonder that I find subjective nostalgia subtly influencing my feelings about Myra Breckinridge each time I revisit it.

It's hard not to sigh at the lost opportunities (for Vidal's novel is quite funny), but when I watch the film now it is with a lighter spirit and a forgiving perspective born of having lived long enough to see what has become of the reckless instincts that spawned Hollywood's interest in Myra Breckinridge in the first place. In light of today's Hollywood of market research, endless franchises, and bottomless remakes, the foolhardiness which prompted the greenlighting of Gore Vidal's arguably unfilmable novel looks positively courageous by comparison.

BONUS MATERIAL

Not to be missed: A YouTube clip of Raquel Welch on The Dick Cavett Show in 1970. Welch (who has since lightened up quite a bit) is heavily into her "I'm a serious actress!" phase, thus, watching her espousing at pretentious length Myra Breckinridge's merits makes for riotously fun rear-view TV viewing. Bonus laughs materialize when Welch finds her self-serious pomposity continuously deflated by the gentle directness of Janis Joplin. (See it HERE)

It's hard not to sigh at the lost opportunities (for Vidal's novel is quite funny), but when I watch the film now it is with a lighter spirit and a forgiving perspective born of having lived long enough to see what has become of the reckless instincts that spawned Hollywood's interest in Myra Breckinridge in the first place. In light of today's Hollywood of market research, endless franchises, and bottomless remakes, the foolhardiness which prompted the greenlighting of Gore Vidal's arguably unfilmable novel looks positively courageous by comparison.

BONUS MATERIAL

Not to be missed: A YouTube clip of Raquel Welch on The Dick Cavett Show in 1970. Welch (who has since lightened up quite a bit) is heavily into her "I'm a serious actress!" phase, thus, watching her espousing at pretentious length Myra Breckinridge's merits makes for riotously fun rear-view TV viewing. Bonus laughs materialize when Welch finds her self-serious pomposity continuously deflated by the gentle directness of Janis Joplin. (See it HERE)

|

| Myra- "God bless America!" Leticia- "God help America!" |

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2013

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)