I've a feeling an individual can easily gauge what his or her overall

response to this film is likely to be simply based upon how one reacts to its

title. If Puzzle of a Downfall Child strikes you as a potentially profound,

enigmatically poetic title conjuring up images of Paradise Lost and existential

disillusion, you’re likely to fall in love with this long-considered-lost

exemplar of European-influenced, '70s “personal statement” cinema. On the other

hand, if the title reeks of self-serious pretentiousness and needlessly arty ambiguity…well,

little about the film itself is likely to alter that perception.

Faye Dunaway plays Lou Andreas Sand (nee Emily Mercine), an emotionally fragile former high-fashion model who has retreated to a solitary beach house on Fire Island following a crippling nervous breakdown. Visited by long-time photographer friend and former lover Aaron Reinhardt (Barry Primus), Lou recounts her troubled life in a taped conversation Reinhardt hopes to fashion into a film. With her life revealed in flashbacks that come at us in stylized and realistic non-linear stretches devoid of obvious hints as to their veracity as memory, fantasy or both; Lou reveals herself to be the most unreliable of narrators. Yet the tone of these mental images, playing out like scrapbook pages torn from an album and reassembled, expose the truth of the woman, if not always the truth of the events themselves. It's a fascinating narrative path made all the more so due to Puzzle of a Downfall Child being a film constructed in much the same manner. That the movie creates for us a sense that we are watching just the sort of film Primus' character is likely to assemble from his talks with Lou is just one more piece of Puzzle of a Downfall Child 's continually self-referential puzzle.

Director Jerry Schatzberg, who had worked for more than 20 years as a photographer for magazines like Vogue, Esquire, and McCall's, based Puzzle of a Downfall Child on taped interviews he conducted with one of his favorite subjects, 1950s supermodel Anne St. Marie. St.Marie, like her film counterpart, retired from modeling after suffering a nervous breakdown. To further the whole wormhole effect of this enterprise, Schatzberg, who was rumored to have had an affair with St. Marie (as does his screen doppelganger, photographer Aaron Reinhardt with Dunaway's Lou Andreas Sand) in real life photographed Dunaway for many fashion magazines, and for a time the two were engaged to be married. Their relationship had already dissolved before Puzzle of a Downfall Child went before the cameras.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

To its credit, Puzzle of a Downfall Child tries to find the common thread of humanity in the privileged-class despair of Lou Andreas Sand. And as embodied by Dunaway and captured by Schatzberg’s loving camera lens (actually cinematographer Alex Holender of Midnight Cowboy), Lou may never look less than exquisite (even when in the throes of a foaming-at-the-mouth nervous breakdown), but her pain is recognizable and real.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

To view some of Jerry Schatzberg's magnificent photographs, visit his website HERE

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2013

Me, I fall a little into both camps. For one, I've always been crazy about the title. Perhaps that's because I was 13 years old when the movie came out and the title sounded just gloomily cryptic enough to appeal to my adolescent taste for high-flown self-dramatization. (In an interview, director Jerry Schatzberg has stated that the title alludes to a plot element involving an abortion that was deleted in an early draft of the screenplay.) I adore Puzzle of a Downfall Child for its

introspective examination of the elusiveness of happiness and the human desire

to connect in the face of reality-distorting conceptions of image, sexuality,

self-worth, and success. In the telling, few of the film’s insights are

very acute, but there’s a psychological authenticity to the screenplay and

performances which significantly mitigate the sometimes arthouse excesses of the

film’s visual style.

Which leads to camp #2. As much as I love Puzzle of a Downfall Child and believe it to be both a beautiful and moving film, I’m the first to admit that at times it can feel like a parody of a '70s art film. The debut effort of photographer turned-director Jerry Schatzberg, Puzzle of a Downfall Child falls prey to the minor sin of over-determined significance. There’s a kind of naïve foolhardiness to be found in acts of absolute sincerity, and if Puzzle of a Downfall Child suffers from anything, it’s from a heartfelt conviction it is saying something “important” about the human condition. To some, such ponderousness can come off as pretentious, humorless, or just plain exasperating. But me, I’ll take a self-serious film that tries to be about something over today’s cynical, eye-on-the-boxoffice, market-research product any day.

Which leads to camp #2. As much as I love Puzzle of a Downfall Child and believe it to be both a beautiful and moving film, I’m the first to admit that at times it can feel like a parody of a '70s art film. The debut effort of photographer turned-director Jerry Schatzberg, Puzzle of a Downfall Child falls prey to the minor sin of over-determined significance. There’s a kind of naïve foolhardiness to be found in acts of absolute sincerity, and if Puzzle of a Downfall Child suffers from anything, it’s from a heartfelt conviction it is saying something “important” about the human condition. To some, such ponderousness can come off as pretentious, humorless, or just plain exasperating. But me, I’ll take a self-serious film that tries to be about something over today’s cynical, eye-on-the-boxoffice, market-research product any day.

|

| Faye Dunaway as Lou Andreas Sand |

|

| Barry Primus as Aaron Reinhardt |

|

| Viveca Lindfors as Pauline Galba |

|

| Roy Scheider as Mark |

|

| Two magazine covers photographed by Jerry Schatzberg Left: Anne St.Marie -1956 / Right: Faye Dunaway - 1968 |

Director Jerry Schatzberg, who had worked for more than 20 years as a photographer for magazines like Vogue, Esquire, and McCall's, based Puzzle of a Downfall Child on taped interviews he conducted with one of his favorite subjects, 1950s supermodel Anne St. Marie. St.Marie, like her film counterpart, retired from modeling after suffering a nervous breakdown. To further the whole wormhole effect of this enterprise, Schatzberg, who was rumored to have had an affair with St. Marie (as does his screen doppelganger, photographer Aaron Reinhardt with Dunaway's Lou Andreas Sand) in real life photographed Dunaway for many fashion magazines, and for a time the two were engaged to be married. Their relationship had already dissolved before Puzzle of a Downfall Child went before the cameras.

|

| "If one can't keep some friends somewhere, then something is really wrong." |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

I think perhaps my favorite thing about Puzzle of a Downfall Child is that it combines two of my favorite film

genres: the '70s trying-to-find-oneself character drama and the '40s

suffering-in-mink women’s weepie. How perfect is that? When I first saw this film, Faye Dunaway’s too-sensitive-for-this-world fashion model was

an oasis of estrogen ennui in the testosterone-leaden desert of male-centric '70s films

romanticizing male identity crises and masculine existential moments of reckoning. To my taste, there was a decided oversupply of movies featuring the likes of Jack Nicholson, George

Segal, Richard Benjamin, or Elliot Gould grappling with the meaning of life, while an uncomprehending female (usually a sweet-natured dumbbell, and almost

always played by Karen Black) stood around on the sidelines. Aside from the vastly

inferior (by comparison) Jacqueline Bisset drama, The Grasshopper (1969), Puzzle

of a Downfall Child was one of the few films from this era to grant a female

character an equivalent navel-gazing opportunity.

|

| To update Easy Rider's famous tagline, Puzzle of a Downfall Child could have been subtitled: "A woman went looking for America and couldn't find it anywhere." |

To its credit, Puzzle of a Downfall Child tries to find the common thread of humanity in the privileged-class despair of Lou Andreas Sand. And as embodied by Dunaway and captured by Schatzberg’s loving camera lens (actually cinematographer Alex Holender of Midnight Cowboy), Lou may never look less than exquisite (even when in the throes of a foaming-at-the-mouth nervous breakdown), but her pain is recognizable and real.

Have you ever seen an old detective movie or TV show and

marveled at the perversity of (male) cops and reporters at a murder scene going on and

on about how beautiful or desirable a female corpse was? I can't count the number of films I've seen where men stand over a dead woman's body lamenting the "waste" of a beautiful woman and how particularly tragic it is that said woman, so pretty or sexy in life, is now dead. It’s like there’s this

overriding mentality that a woman’s looks and physical appeal matter even in

death. Or worse, that one can be too beautiful to die...as if the loss of life

is sad, but the tragedy is compounded if the corpse is a looker.

Puzzle of a Downfall

Child sensitively addresses the high value we, as a culture, place on beauty, and the

price exacted on those who fall prey to it. In placing this character drama in

the appearance-fixated world of fashion photography, Schatzberg and

screenwriter Carole Eastman take an insightful look at a woman whose entire existence

and sense of self-worth is tethered to her beauty. Whose need to please and always be

seen as desirable under the male gaze is both a desperate, deep-seated search

for approval and a profound denial of self. The film's definitive narrative thread calls attention to the pervasiveness of male exploitation and the vulnerability/susceptibility of the female form.

PERFORMANCES

|

| Beauty: Fetishism and Objectification |

PERFORMANCES

Faye Dunaway’s participation was instrumental in getting Puzzle of a Downfall Child to the screen, and her passion for the project is evident in every frame. And it’s a good thing too, because

to the best of my recollection there isn't a single scene in which she does not

appear. Mind you, I'm not complaining, for in much the manner that Liza Minnelli is so good in Cabaret that she makes you forget

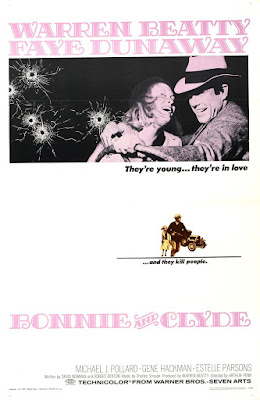

“Liza Minnelli: The Home Shopping Network Years”; Faye Dunaway so thoroughly blows me away in Puzzle of a Downfall Child that I'm reminded of everything her career promised before the whole Mommie Dearest / voicemail meltdown thing. One of my favorite but most problematic actresses (you have to have a taste for her mannerisms), Dunaway has every reason to be very proud of her work in this. After Bonnie & Clyde, Puzzle of a Downfall Child ranks as my all-time favorite Dunaway film. She is phenomenal in it.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

I tell everyone, even if you don't have the patience for the entire film, just watch the first 15 minutes. The sequence chronicling Dunaway as a fledgling model navigating the battlefield of her first fashion shoot is cinema gold. Shot with an eye for detail only possible from knowing this world very well, Schatzberg peels back the illusions we hold in our America's Next Top Model preoccupation with the fashion industry and reveals the dehumanizing reality. Sure it's satirical, sure it's depicted from the overwrought perspective of the heroine; but from the performances, the dialogue (tellingly, Lou's voiceover describes the men on the set all looking at her as if they were sex maniacs. The visuals reveal her to have been largely ignored), and the stylish cinematography, this sequence is a great example of MY kind of moviemaking.

|

| Dunaway reacts (I'll say) to being required to share her close-up with a live falcon. This terrifying sequence recall actress Tippi Hedren's accounts of working with Hitchcock on The Birds. |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

One of the good things about viewing an old film (and at 43

years-old Puzzle of a Downfall Child definitely

qualifies) is that one gets to watch it

in an environment entirely different from that in which it was created. Puzzle of a Downfall Child bombed in part

because it came at a time when audiences were wearying of the glut of European-influenced,

tarnished American Dream films that filled theaters after the breakthrough

years of 1967. When viewed from the comic book / 3-D / blockbuster perspective

of today, the film looks nothing short of miraculous.

As a culture, we’re guilty of attributing great profundity to the existential midlife traumas of male characters in films, while women undergoing the same are dismissed as merely neurotic. (I don’t know where I read it, but someone once observed that The Graduate missed the boat in focusing on the petulant Benjamin Braddock when the film's most compelling story and most interesting character was Mrs. Robinson and her midlife dissatisfaction.) It’s difficult not to think this subtle double standard played into the critical response to Puzzle of a Downfall Child, but as good as the film is (and I think it’s a really excellent film) there’s no ignoring that it falls into the usual traps that beset movies that ask us to feel sorry for the beautiful people.

As a culture, we’re guilty of attributing great profundity to the existential midlife traumas of male characters in films, while women undergoing the same are dismissed as merely neurotic. (I don’t know where I read it, but someone once observed that The Graduate missed the boat in focusing on the petulant Benjamin Braddock when the film's most compelling story and most interesting character was Mrs. Robinson and her midlife dissatisfaction.) It’s difficult not to think this subtle double standard played into the critical response to Puzzle of a Downfall Child, but as good as the film is (and I think it’s a really excellent film) there’s no ignoring that it falls into the usual traps that beset movies that ask us to feel sorry for the beautiful people.

Film is a storytelling medium and all manner of human

experience should be explored. But films like Puzzle of a Downfall Child seem to forget why movies exist and who

attends them. No matter how masterful

the film, it’s difficult to ask an audience to listen to a woman as breathtakingly

beautiful as Faye Dunaway complaining about how unhappy she is in her (perceived glamorous)

job as a fashion model, and how empty she finds her life (after amassing enough wealth to live in financially independent solitude in a spacious beach house).

We all know that the rich and beautiful can suffer as much as the rest of us, but any film

that attempts to dramatize a shared humanity with people whose lives offer far more options than those of the average person has to walk a precarious tightrope. If the world is too glossy, the people too lacquered, it can actually end up glamorizing that which it's trying to vilify. Ultimately sending a message similar to

the one expressed by those cops in the old movies bemoaning the fact that certain people are just “Too beautiful to suffer, too lovely to die.”

As of this writing, The DVD of Puzzle of a

Downfall Child is currently only available in France (released Feb. 2012), but every year more and more obscure films are getting "made to order" releases, hopefully this will be one of them.

So, whether you take the film to your heart (as I did), or

wish to wallow in its camptastic splendor (Puzzle of a Downfall Child is an exquisite, sumptuous-looking film

that has a scene involving a toilet that is sure to send Mommie Dearest fans into

wild ecstatics), this artifact from the days when movies sought to do more than make Variety's Top Ten weekend boxoffice list, has a little of something for everybody.

No matter how you prefer your Dunaway, overdone and theatrical or touching and deeply affecting, Puzzle of a Downfall Child is a lost miracle of a film that is worth taking the time to discover (or rediscover).

|

| "One only breaks oneself apart in order to put oneself back together again...better." |

To view some of Jerry Schatzberg's magnificent photographs, visit his website HERE

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2013