"We're on a mission from God."

The first thing I think about when I think about The Blues Brothers is that it opened in

Los Angeles on the exact same day as Can't Stop the Music. Yes, on Friday, June 20th, 1980, two big-budget,

heavily-promoted Hollywood musicals played within blocks of one another on

Hollywood Boulevard. One R-rated, the other PG, each a pre-fab pre-marketed project pitched to a specific (polar opposite) audience demographic. The timing of the release of Cant Stop The Music couldn't have been less fortuitous; the unanticipated success of The Blues Brothers spearheaded an R&B music resurgence and spawned a dreadful sequel. But as dissimilar as these two films appear to be on the surface, they have much in common.

It can be argued that both bands benefited significantly from white

America's preference for the watered-down interpretations of musical styles rooted in the

Black American experience. Disco having developed from dance R&B and funk, while the blues came out of jazz and classic R&B. The "novelty act" identities of both bands was a form of winking pop-cultural pretense allowing the bands to market themselves in ways that expanded their appeal beyond the scope of their music. The Greenwich Village "types" that gave the Village People their costuming enabled the band to have it both ways: they were a gay band for those who "got" the coding; to the rest, they were just a party band. The Blues Brothers more or less updated an ages-old music industry trope: white audience resistance to Black artists allows mediocre covers performed by white musicians to outdistance the far earthier (re: too Black) originals.Both are expensive pop musicals structured as the fictionalized biographies of

real-life "manufactured" musical acts that found unexpected success and a curious form of legitimacy during the late 1970s. I say curious because, to some extent, both The Blues Brothers and The Village People are novelty acts that were taken seriously as musicians after becoming chart-topping record sellers and popular touring acts. The acts themselves: The Village People was chiefly a collection of costumed dancers

marching behind a talented lead vocalist; The Blues Brothers, two costumed Saturday

Night Live alumni assuming alter-identity roles as the fictional characters fronting a band

of genuinely accomplished musicians.

To achieve the kind of mainstream success necessary to turn a profit, the PG-rated, $20 million Can't Stop the Music needed to downplay The Village People's gay disco origins and hopefully attract the same clueless pop/teen record-buying audience that incredibly never picked up on the group's homoerotic costuming or the gay subtext of songs like YMCA and Macho Man.

For The Blues Brothers

to succeed, this R-rated, $27 million well-intentioned "Tribute to African- American

music" (sentiments expressed by both Aykroyd & Belushi) had to play up the

faux "soul" personas of its two white male stars whose chief demographic, via SNL and Animal House, was 20-something straight white males. All the while exploiting the

fleeting "guest star" presence of Black entertainers who were the genuine article: i.e., true legends from the worlds of blues, jazz, and R&B.

In short- Can't Stop the

Music featured a gay band playacting as straight, and The Blues Brothers band featured two frontmen playacting at being Black.

In 1980, I was personally far too much into disco to even consider going to see The Blues Brothers, the first two weekends of its release finding me at the Paramount Theater (now The El Capitan) on Hollywood Blvd watching Can't Stop the Music playing to a near-empty house. I didn't actually see The Blues Brothers until after Xanadu had opened the following month. By then, the poorly-reviewed Belushi/Aykroyd starrer had already emerged as the hit of the summer... coming in second only to The Empire Strikes Back.

I can't profess to ever have been a big fan of SNL, I've never seen Animal House, and the appeal of John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd was largely lost on me. So when they began appearing in concert as The Blues Brothers, opening for a young Steve Martin, I was among those baffled by their success. I genuinely thought their chart-topping 1978 LP "Briefcase Full of Blues" was a comedy album. I suspect my reaction to The Blues Brothers as a legitimate musical act was very likely similar to how rock fans reacted to The Monkees in the '60s.

|

| Chaka Khan has a cameo as a member of the Triple Rock Baptist Church choir |

But despite my initial misgivings, John Landis' The Blues Brothers ultimately did more than win me over; I actually fell in love with it. This ragtag tale of two musical miscreants on a mission of reform took me back to my childhood; the film struck me as a hip update of those overblown slapstick chase comedies like The Great Race (1965), crossed with a hip Bob Hope Bing Crosby vibe, all added to one of those all-star cameo epics like Around the World in 80 Days (1956). Set in contemporary Chicago, the tone of The Blues Brothers and its depiction of Black culture is forever skirting the fine line between veneration and patronization (the Black artists are the supporting cast in a film dedicated to the music they invented). Still, the overall cleverness and humor of the film allow it to coast a great deal on good intentions, goodwill, and the exhilaration that comes from The Blues Brothers being a bang-up, enjoyably silly musical comedy.

|

| Kathleen Freeman as Sister Mary Stigmata (The Penguin) |

|

| Carrie Fisher as the Mystery Woman |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

That The Blues Brothers is now considered by many to be a classic (and deservedly so, in my opinion) has much to do with its age. Now almost 40 years old, many of the film's biggest fans discovered it on cable TV as kids, citing it as the first R-rated movie they ever saw. It also doesn't hurt that the film was a major boxoffice success, ranking as the 10th highest-grossing film of 1980. But, linked as it is to the glory days of SNL, The Blues Brothers earns its status as a classic because it's remembered fondly for its guest roster of musical greats. Even if you don't care for the film, there's no denying that something about The Blues Brothers seized the public's imaginations enough for the group to become a household name and pop phenomenon. And like the film it most resembles—the equally unwieldy and intermittently funny car chase comedy It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963) —The Blues Brothers is a product of a distinct era (the post-'70s blockbuster days of pre-CGI excess) and features the final or only screen appearances of several entertainment industry greats no longer with us. In that respect, it can't help but look great from a rear-view perspective.

I was a huge fan of The

Blues Brothers in 1980, seeing it so many times I could repeat jokes

and recite verbatim bits of dialogue. I still enjoy it a great deal, but upon

revisiting it recently via the extended Blu-ray edition (approximately 15-minutes longer than the theatrical), it became clearer to me that the music and musical sequences are where my heart lies. They're so good they tend to make me forget that the deadpan give-and-take between Jake and Elwood can feel a little draggy. The film's soundtrack is a major saving grace, the personal nostalgia dredged up by the songs reminding me of the music my parents used to play around the

house when I was a kid. It's only humor-wise where things start to get dicey for me. Aykroyd comes off as a nice kind of goofus type, but (and I know I'm alone in this) I honestly don't get Belushi's appeal. I kept waiting for him to catch fire on the screen, to show some flash of comic brilliance... but, zip. He starts out and remains a fairly inert presence. The contributions of the guest stars and cameos are fun, as are the almost surreal touches of over-scale lunacy that give the film the feel of a live-action Bugs Bunny cartoon.

|

| Twiggy as The Chic Lady |

The whole viewing experience reminded me of when I

tried relistening to one of those '70s Cheech & Chong comedy albums that

were all the rage when I was in high school. Verdict: WTF?

|

| Henry Gibson as the Head Nazi |

|

| Steve Lawrence as Maury Sline |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

For many, The Blues Brothers endures because of its standing as a filmed record of so many now-deceased legendary Black artists from the worlds of jazz, R&B, gospel, and blues. In a year that saw the release of many large-budget musical films--Xanadu, Popeye, Coal Miner's Daughter, The Apple, The Jazz

Singer (which gave us Neil Diamond in blackface, fer chrissake), and Can't Stop the Music --The Blues Brothers was the only one with soul. Too bad the only way to access it was after Belushi and Aykroyd had relinquished the spotlight.

The Blues Brothers shines brightest in its musical interludes. And what a treat it is to see Aretha Franklin in her first movie appearance, James Brown singing gospel, Cab

Calloway in Technicolor, and a street full of Chicago residents doing the twist

to Ray Charles (the latter being the image that most stuck in my mind the first time I saw the film's trailer.)

Choreographed by the late Carlton Johnson (familiar to many

as the sole Black male member of the Ernie Flatt Dancers on The Carol Burnett Show), each number is

a standalone set piece staged with witty exuberance and cinematic

panache.

My favorites, in order of preference:

Ray Charles - "Shake a Tailfeather"

Ray Charles really blows the roof off with his driving rendition of this upbeat R&B dance tune first sung by The Five Du-Tones in 1963, making it more than fitting that the number spills out into the Chicago streets, inspiring the first flash mob. Playing the proprietor of Ray's Music Exchange, where the band goes to purchase instruments, Charles' infectiously soulful vocals are so raw and playful that he fairly dares you to stay in your seat. Which makes it so ideal that the throngs of amateur dancers outside his store so enthusiastically accommodate his requests for a rundown of the popular dances of the '60s. I love absolutely everything about this number, which is the most assured in terms of choreography, staging, and editing. Just brilliant. Watch a clip of it HERE.

|

| The center member of the Soul Food Chorus is Aretha Franklin's younger sister Carolyn |

Aretha Franklin - "Think"

Although she briefly sang and acted in a 1971 episode of TV's Room 222, The Blues Brothers marks Aretha Franklin's film debut. Cast as the wife of Blues Hall of Fame inductee Matt "Guitar" Murphy, Franklin's now-iconic performance of her 1968 hit "Think" is both rousing and an uncontested high point in the film. Many consider it the best number in the film, something I wouldn't necessarily argue with, save for a quibble or two. No one can fault Franklin's peerless performance and star quality, but my problem (and this is likely due to the multiple takes required due to Franklin's discomfort with lip-syncing) but the editing feels soggy and screws with the song's rhythm. Plus the imprecise staging frequently leaves Franklin not knowing what to do with her arms or body as she waits for the next verse.

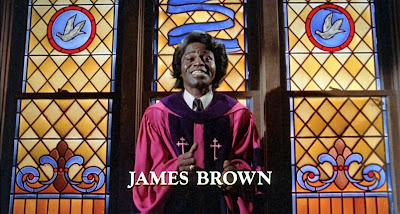

James Brown - "The Old Landmark"

Jake and Elwood find religion and a higher purpose at the Triple Rock Baptist Church listening to the sermon of Rev. Cleophus James. And who wouldn't in the presence of The Godfather of Soul himself, James Brown? When the Reverend and his choir break into this 1949 gospel standard (which Brown had never heard of before) the church erupts into a jubilant revival production number that literally defies gravity. James Brown (a personal favorite) is dynamic as all get-out in this, the film's first musical set-piece, whose contagious energy and gymnastic, high-kicking dancers get things off to a very spirited start.

Cab Calloway - Minnie the Moocher

A delightful moment that I recall brought a round of applause from the movie theater audience I saw this with, was when 72-year-old Cab Calloway, as Curtis, the janitor at the orphanage where Jake and Elwood were raised, entertains a restless audience by magically morphing into the 1930s incarnation of the Big Band Cab Calloway we all remember (transforming the stage and the motley band members along with him). In the theatrical release, this stylish highlight was marred by cutaways to the tardy Blues Brothers trying to make it to the theater. The restored Blu-ray allows us to see more of Calloway's hep rendition of his 1931 signature song. A song he co-penned with Irving Mills, and which was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999, five years after Calloway's death.

|

| Paul Reubens (Pee Wee Herman) as a waiter at the Chez Paul restaurant |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

As my partner can attest, a favorite phrase of mine

is "Two things can be true at once." A phrase that comes in particularly handy when

writing about film. Take, for example, the observation that Faye Dunaway is an unrepentant

ham, while at the same time being an absolutely brilliant actress. Both are circumstantially true, resulting in the truth of one not negating the truth of the other. It's all a matter of perspective.

As per The Blues

Brothers: It's true the film and its makers provide a respectful and, in

some instances, classic showcase for Black artists ignored by Hollywood. It's a

fact that Aykroyd and Belushi used the privilege of their fame and took a risk

on the moneymaking potential of the film by insisting on hiring these legendary

Black stars and featuring so many Black faces in the supporting cast. (Theater

distributors like Mann's Westwood, not wanting what they perceived to be a "Black

film" in their neighborhoods, wound up cutting The Blues Brothers opening venues by more than half.) It's also

true The Blues Brothers was

instrumental in a whole new generation of people discovering music and artists that white record companies and radio stations had long ignored.

All that being said, it's also true that The Blues Brothers is almost embarrassing as an example of cultural appropriation. When my parents (who grew up on real blues

and jazz) watched The Blues Brothers on cable TV many years ago, their takeaway

was that the Black performances in the film reminded them of the days when Lena

Horne would appear in isolated numbers in MGM musicals so that her scenes could

be edited out when the films played in the South.

Subtextually, Black culture is used as a backdrop in The Blues Brothers, a thing Jake and

Elwood have free access to lay claim to and use in any way they wish. Black

music is theirs to perform, Black personas are theirs to adopt; all the while they're

secure in the fact that they don't even have to be any good to succeed—they merely

have to be Not Black. An unfortunate fact borne out by the music history statistic that both The Blues Brothers soundtrack and the

aforementioned Briefcase Full of Blues rank as the top-selling blues albums of all time. My head hurts just thinking about

that one.

|

| Critics of the film rightfully question whether the humor of The Blues Brothers is rooted in merely seeing whites occupying Black spaces |

|

| Steven Spielberg as the Cook County Office Clerk |

BONUS MATERIAL

A poorly-received Blues Brothers sequel--Blues Brothers 2000--was made in 1998, some 16-years after John Belushi's death. Co-written by Aykroyd and Landis, this PG-13 misguided venture brought back several members of the original cast (Aretha Franklin, James, Brown, Steve Lawrence, Kathleen Freeman) but to less entertaining effect. Budgeted at $28 million, it grossed something in the neighborhood of $14 million. I tried watching it, but the introduction of that kid Blues Brother did me in.

|

| Choreographer Carlton Johnson staging Franklin's "Think" musical number |