Before Drew Barrymore, Matthew McConaughey, Katherine Heigl, and the entire Judd Apatow oeuvre conspired to sour me on

the whole genre for good, I really used to love romantic comedies. To me, the

absurdist roundelay that is two human souls striving to connect is marvelous

fodder for films both touching and hilarious. In that vein, Two for the Road, Ball of Fire, and Sweet

November (the 1968 version) are among the funniest, most engagingly romantic

films I've ever seen. But I don't think they make those kinds of romantic comedies anymore.

There seems to be a post-feminist hostility embedded in romantic comedies today: a passive-aggressive assignment of all things emotional to “chick flick” dismissiveness, combined with a self-serving aggrandizement of all things boorish and sophomoric to the realm of masculinity. Maybe it’s time for me to explore what’s out there in gay-themed romantic comedies, because the heterosexual battle of the sexes seems to have grown increasingly reductive and mean-spirited.

There seems to be a post-feminist hostility embedded in romantic comedies today: a passive-aggressive assignment of all things emotional to “chick flick” dismissiveness, combined with a self-serving aggrandizement of all things boorish and sophomoric to the realm of masculinity. Maybe it’s time for me to explore what’s out there in gay-themed romantic comedies, because the heterosexual battle of the sexes seems to have grown increasingly reductive and mean-spirited.

One particular favorite of mine from the past is Starting Over, an almost forgotten romantic

comedy smash from 1979 (one of the top 20 highest-grossing films of the year)

directed by Alan J. Pakula (Klute, Sophie’s Choice) and written by James L.

Brooks (The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Terms of Endearment).

|

| Jill Clayburgh as Marilyn Holmberg |

|

| Burt Reynolds as Phil Potter |

|

| Candice Bergen as Jessica Potter |

|

| Charles Durning and Frances Sternhagen oozing well-intentioned sincerity |

I don’t have a whole lot of objectivity where Starting Over is concerned. Not to the degree that I’m

blind to the film’s faults, but in as such that my abiding fondness for the

film seems inextricably tied to my feelings about the time in which it was made (the late '70s) and my initial response to it when I first saw it (it rivaled What's Up, Doc? as one of the funniest comedies of the time). In other words, this might be one of those films about which I rave

from the housetops, yet could very likely leave those seeing it for the first

time feeling a little underwhelmed.

I guess it's good for me to remember that the proper response to some films (like jokes that don't translate) can only be, “You had to have been there.” Starting Over was released at the very tail-end of the 1970s and a great deal of its humor is derived from its so perfectly capturing the zeitgeist of that particular point in time. Pop history (and especially historical motion pictures) would have us believe that eras begin and end neatly and succinctly, but in truth, time has a tendency to overlap, and trends and cultural preoccupations sort of bleed into one another.

I guess it's good for me to remember that the proper response to some films (like jokes that don't translate) can only be, “You had to have been there.” Starting Over was released at the very tail-end of the 1970s and a great deal of its humor is derived from its so perfectly capturing the zeitgeist of that particular point in time. Pop history (and especially historical motion pictures) would have us believe that eras begin and end neatly and succinctly, but in truth, time has a tendency to overlap, and trends and cultural preoccupations sort of bleed into one another.

|

| The underutilized Mary Kay Place (Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman) is extremely funny as a particularly awkward bind date |

In 1979, the narcissism of the “Me” decade began to be co-opted by yuppies and started to transmogrify into a new kind of unashamed era of self-interest and self-realization. It was an era of encounter groups, self-help books, and a whole lot of psychoanalytical navel-gazing. Of course, all this preoccupation with self would eventually lead to the “Decade of Greed” that became the '80s; but in 1979 all this meant was that everyone was caring, sharing, and feeling feels all over the place. The drug-fueled hedonism of the swinging-singles disco era led to a post-sexual revolution ennui mixed with singles-bar aimlessness (captured the previous year in the morbidly moralizing 1978 film Looking for Mr. Goodbar) that in turn boosted divorce rates and threw male/female relationships into a tailspin.

|

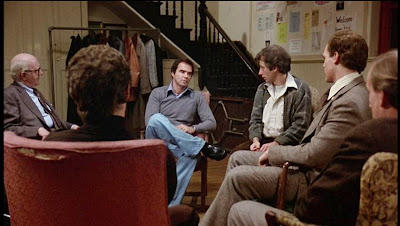

| At the urging of his brother, Phil (Reynolds) attends a divorced men's workshop. That's What's Up, Doc?'s Austin Pendleton to the right. |

After her Oscar-nominated emergence in 1978's An Unmarried Woman, Jill Clayburgh became the unofficial screen spokesperson for modern womanhood. She was a real favorite of mine and is sensational here. The progressive feminine image she presented—of a woman who wanted, not needed a man—would become fairly obsolete by 2012 thanks to the regeneration of the Disney Princess Myth and TV reality show humiliations like The Bachelor and Who Wants to Marry a Millionaire?

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT

THIS FILM

As stated, the thing I most enjoy about Starting Over (and something I’m not at all sure carries over to those discovering the film today) is how wittily the film captures the tenuous, walking-on-eggshells state of

male/female relationships in the '70s. The 1970s was culturally the decade where

all the dust was settling from the upheavals of the 60s, and people were these

vibrating bundles of anxiety putting herculean effort behind maintaining a

front of laid-back serenity. (The sale of Valium skyrocketed in the '70s; a fact

inspiring one of Starting Over’s biggest

and then most talked-about gags).

Traditional gender roles, those typified by the Rock Hudson/Doris Day comedies of the '60s,

were dismantled in the '70s, necessitating a new kind of sex comedy. Ads for Woody Allen’s

Annie Hall (1977)—the real game-changer

in romantic comedies—labeled it “A Nervous Romance.” That classification goes

double for Starting Over; only instead

of urban singles, were invited to enjoy the amorous fumblings of the newly divorced. Individuals who perhaps married when one set of rules was in place, forced to re-enter single life ill-prepared for the cultural change-up in the game plan.

|

| Phil suffers a panic attack at Bloomingdale's |

|

| Love, American Style (I've always loved that print that hangs above them: "Woman Reading" by Will Barnet) |

PERFORMANCES

Few who

weren’t around to bear witness to the painful spectacle of Burt Reynolds’ willful

self-exploitation and wasting of his talents in the '70s can't appreciate what a

delightful departure (and surprise) Starting

Over was. The promising performer of Deliverance (1972) spent the better part

of the decade ignoring his gifts as an actor, instead choosing to court dubious

celebrity and fashioning himself into the male Jayne Mansfield (or the Matthew McConaughey) of the '70s. One of the

biggest (if not the biggest)

box-office stars of the time, Reynolds, with his myriad talk-show appearances,

gleeful self-objectification, and seemingly

endless stream of unwatchable, good ol’ boy redneck comedies, enthusiastically participated

in turning himself into a Hollywood punchline.

Divested of his trademark pornstache and dropping his tired Dean Martin-esque "I'm so cool I don't care" indifference act; Reynolds gives perhaps his best pre-Boogie Nights performance in Starting Over. I don’t know that I've ever found Reynolds to be particularly likable before, but here he is quite appealing and quite wonderful. Underplaying marvelously, he’s one of the few male characters on screen able to convey a sweetly insecure vulnerability without slipping into wimpdom.

Divested of his trademark pornstache and dropping his tired Dean Martin-esque "I'm so cool I don't care" indifference act; Reynolds gives perhaps his best pre-Boogie Nights performance in Starting Over. I don’t know that I've ever found Reynolds to be particularly likable before, but here he is quite appealing and quite wonderful. Underplaying marvelously, he’s one of the few male characters on screen able to convey a sweetly insecure vulnerability without slipping into wimpdom.

Alas,

much in the way Eddie Murphy’s noteworthy performance in Dreamgirls failed to prevent Hollywood from remembering the hot mess that was Norbert; the career turn-around Starting Over may have signaled for Burt

Reynolds was sabotaged by the two-strikes-you're-out disaster followup that was the craptacular Smokey and the Bandit II (1980) and The Cannonball Run (1981).

|

| The ultimate sign of commitment: giving your sweetheart the key to your apartment |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Without a doubt, the biggest buzz attending Starting Over on its release was the breakout comedy

performance of Candice Bergen. Never highly-regarded for her acting, but a

popular screen presence due to roles capitalizing on her ice-princess beauty, Bergen

had heretofore only shown her comedic side on television (she was the first

female host of Saturday Night Live

and appeared to great effect on The

Muppet Show). As Starting Over’s self-confident,

atonal singer of atrocious “empowerment” pop songs, Bergen garnered the best

notices of her career and, at age 32, launched a second career of sorts as

a skilled comedienne.

The songs attributed to Bergen’s character were written by then-collaborative-couple Carole Bayer Sager and Marvin Hamlisch, whose own relationship they immortalized in the Neil Simon-penned Broadway musical They’re Playing Our Song (1978). I'd always thought Bergen’s songs in Starting Over were intended to be awful, both musically and lyrically (although I can’t help liking the song “Better Than Ever.” Oddly enough, Bergen’s version more than the Stephanie Mills version heard at the end), but in truth, they sound identical to the songs from their hit Broadway show, so maybe they aren't as satiric as I once assumed.

|

| Future Murphy Brown co-star, Charles Kimbrough, has a bit part as a salesman |

|

| Home Alone's Daniel Stern (who would also appear in the Jill Clayburgh films I'm Dancing as Fast as I Can and It's My Turn) plays a student in Burt Reynolds' journalism class in Starting Over |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

Starting Over is a terrifically funny and touching romantic comedy, but I can understand if time has diluted some of its punch. For one, the image of Burt Reynolds as a wiseguy sex machine is so dim now that no one is likely to derive much pleasure from seeing him cast against type. Seeing Burt Reynolds without his mustache in 1979 would be today akin to seeing Lady Gaga wearing Crocs.

Similarly, most people's memory of Candice Bergen today only extends back as far as Murphy Brown, so her atypically relaxed and risk-taking performance here lacks the shock value it had in 1979. The same can be said for the humor derived from her terrible singing. The idea of a no-talent pop star was riotous in 1979; folks looking at the film today might well think she sounds no worse than Katy Perry.

Similarly, most people's memory of Candice Bergen today only extends back as far as Murphy Brown, so her atypically relaxed and risk-taking performance here lacks the shock value it had in 1979. The same can be said for the humor derived from her terrible singing. The idea of a no-talent pop star was riotous in 1979; folks looking at the film today might well think she sounds no worse than Katy Perry.

I have no idea why some comedy is enduring (I Love Lucy) while other kinds of humor seem to grow less funny over time (I love the film Shampoo, but I look at it now and can't even remember why I once found it to be so hilarious). Starting Over, for better or worse, bears the stamp of its time, but in a way that I don't think dates it so much as lends its humor an authenticity and its characters a sense of existing in a real-time and place. (Starting Over, which takes place in Boston, has a great look of winter and autumn about it. The huge coats the characters wear look for once like they're actually for function, not fashion, plus, I love that people in this movie use the bus!)

Starting Over is full of '70s-era jokes about finding oneself, Accutron watches, and telephone answering machines, but its sweetly comic look at the need to take chances to find love is something I don't think can ever be labeled dated.

THE AUTOGRAPH FILES

|

| Autograph of Candice Bergen from 1991, at the height of her Murphy Brown fame |

Copyright © Ken Anderson

.JPG)