In writing about films, I'm afraid I'm guilty of coming down pretty hard on the recent spate of comic book movies. My usual gripes:

1. The cloak of self-seriousness they've shrouded themselves

in of late.

2. The need for each successive film in a franchise to be busier, noisier,

and more frenetically-plotted than the last.

3. The gradual usurpation of the kid-friendly genre by adult

males (college-age to middle) willing to come to social media blows and death threats over plot points, casting, trivia, and fidelity to source material. Which, it bears repeating…is a Comic Book.

4. There just being so darn many of them.

Despite their obvious popularity and profitability, I still

stand by my assertion that glutting the market with so much ideologically and

stylistically similar "product" may be good business, but it's lousy art. But whenever I find myself being too much of a curmudgeon about the ceaseless hype surrounding

the latest cookie-cutter entry in the DC or Marvel franchise, I only have to remind

myself of what a flurry of hoopla and excitement I happily allowed myself to

get swept up in way back in 1978.

I don't think there was a soul on earth more charged-up about the release of Superman: The Movie. A film that was then, and remains today, my absolute favorite superhero movie of

all time.

.JPG) |

| Christopher Reeve as Superman / Clark Kent |

|

| Margot Kidder as Lois Lane |

|

| Gene Hackman as Lex Luthor |

|

| Valerie Perrine as Eve Teschmacher |

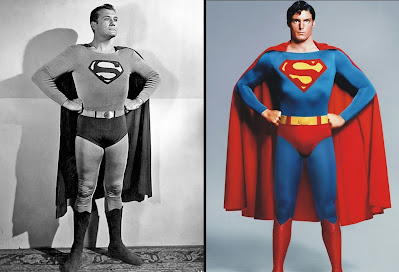

Like many people my age, Superman

comic books and reruns of The

Adventures of Superman TV series (1952-1958) were an inextricable part of my childhood. And, outside of a few Saturday morning cartoons, they were also the only Superman I knew. (The less said about the 1975 TV version of the

1966 Broadway musical, It's a Bird… It's a

Plane… It's Superman the better). So while I dearly loved the TV series, when it was announced in 1976 that a mega-budget, all-star Superman film was going into production, I was overjoyed at the prospect of any form of updating of that program's '50s

sensibilities (gangsters and crime lords), cheesy flying effects, and George Reeves' baggy-kneed Superman

tights.

Interest and excitement intensified as I opened myself up to being subjected to nearly two years of pre-production

hype and advance publicity. I ate it up. By the time the film was set to open, I had whipped myself into a proper frenzy of anticipation.

|

| Marlon Brando and Susannah York as Jor-El & Lara |

|

| Glenn Ford and Phyllis Thaxter as Ma & Pa Kent |

Superman: The Movie opened Friday, December 15th, 1978, at Grauman's Chinese Theater in LA, and, of course, I was

in line opening night. The pre-release press reviews were near-unanimous raves. The film's marketing strategy—minimalist teaser ads dramatically highlighting the Superman insignia and little else—left everyone intrigued yet completely in

the dark. In those pre-internet days, it was easier for movies to keep much of

their content under wraps before release, so buzzing through the waiting crowd that night was the thrill of expectation, wonder, and the sense of being present for an "event."

The first weekend of release saw the theater adding late-night

screenings to accommodate the overflowing masses. The line I stood in (formed at 4pm to get into an 8pm show) wrapped almost around the block. Camaraderie born of the shared battle fatigue of waiting so long revealed that all any of us could talk about was how Superman: The Movie was going to stack

up, special effects-wise, to the previous year's megahit, Star Wars. That, and speculating on how the film intended to make good on the promise of its tagline: "You'll Believe a Man Can Fly."

|

| George Reeves, the Superman of childhood. Christopher Reeve, my favorite Superman of all time. |

Next came the first trumpeting of horns of composer John Williams' majestically heroic score, and with this, absolute pandemonium in the auditorium. The biggest collective

gasp I've ever heard in my life filled the Chinese Theater, followed by applause and thrilled exclamations all around.

Superman

wasn't even two minutes old and already had the audience eating out of its

hand.

|

| Otis (Ned Beatty) and Miss Teschmacher read about the Man of Steel. I think Otis moves his lips. |

Although production on Superman

had begun before Star Wars was released,

Superman: The Movie arose from the

same cultural zeitgeist. In concept and execution, it was another affectionate update and tribute to

the kinds of films that kids of my generation grew up seeing at Saturday matinees. The cynical and disillusioned '70s—whose attitudes echoed the Great Depression of the 1930s—were searching for hope and heroes. (That other Depression Era optimist, Annie, had opened on Broadway just a year before in early 1977.) The simplicity of Superman's motto: a belief in "truth, justice, and the American way," struck a social chord.

Superman: The Movie accomplished the

miracle of being something totally new, yet comfortingly nostalgic. Something sophisticated, yet charmingly corny. Something spoofishly fun, yet respectful of both the Superman

legend and its legions of fans. And, for once, a film had lived

up to its massive hype.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT

THIS FILM:

When action films and summer blockbusters come under critical fire for being moronic, shoddily written, or just a series of explosions and car chases strung haphazardly together (directors Michael Bay and Roland Emmerich come to mind), I always take umbrage when their lazy defense is: "It's not supposed to be taken seriously," "It's pure escapism!", or "It's intended for

kids!"

As children's book authors Dr. Seuss and Roald

Dahl could tell you, kids aren't stupid, and escapist fare doesn't mean mindless.

|

| Jackie Cooper as Perry White |

Expertly balancing ever-shifting tones of adventure, romance, drama, and comedy, Superman: The Movie employs a classic, three-act story structure and finds ways to lend dimension to its comic-book-originated characters.

|

| Jeff East as Young Clark Kent |

I like a Superman who has time to rescue cats from trees and apprehend common thieves. I find the whole "global destruction" angle of contemporary superhero films just too emotionally distancing.

|

| Jor-El sentences Ursa, Non, and General Zod to the Phantom Zone Villains Sarah Douglas, Jack O'Halloran, & Terence Stamp don't really make their presence felt until Superman II (1980) |

PERFORMANCES

During the entirety of my childhood George Reeves and Noel

Neill were the only Superman and Lois Lane I knew. Now, rather spontaneously,

when I think of Superman and Lois Lane, I can only see Christopher Reeve and

Margot Kidder. Their performances have blotted out all prior and subsequent

incarnations of the characters. Both actors are such spot-on, visually witty, temperamentally

ideal incarnations of the characters that they have become Superman and Lois for me.

|

| Lke Jeremy Irons in David Cronenberg's Dead Ringers, Reeve's dual performance involves subtle shifts in body language that transform his features right before my eyes |

I've loved movies all my life, but I've never fully understood that imperceptible, interdependent alchemy the camera captures that accounts for screen chemistry and star quality. It strikes me as a most elusive, ethereal factor, yet the fates of multimillion-dollar movie projects are tethered to it. Both Christopher Reeve and Margot Kidder are fine actors in their own right, but for me, they've never registered as effectively in any other film or with any other co-star. They are magic together, and I treasure every scene they share.

However, I've nothing but unqualified praise for the rest of the marvelous cast assembled.

I sense a great deal of the credit is owed to director Richard Donner (The Omen), who, after setting the right tone and creating a kind of cartoon reality, then has his actors pitch their performances to just the right level of believable and comic. Glenn Ford and Phyllis Thaxter play their scenes with a beautiful, relaxed naturalness that perfectly sets up the "comic book" style acting that takes over when Clark moves to Metropolis. Jackie Cooper's excitable Perry White is one of my favorite performances, and I am particularly delighted by Gene Hackman and his barely-up-to-the-task minions Valerie Perrine and Ned Beatty.

|

| Marc McClure as Jimmy Olsen |

Swoon alert. One of the top reasons Superman: The Movie is my fave rave superhero movie is because I am absolutely enchanted by the Superman/Lois Lane romance. And as embodied by Reeve and Kidder, they make for one of cinema's most charismatic and charming screen couples. I'm a sucker for corny romance anyway, but in taking the time to create a Lois and Clark that are quirky, imperfect, and endearing, Superman made the pair so likable that you're practically rooting for them to fall in love.

*Spoiler Ahead*

I'm well past middle age, I've seen this movie dozens of times, and it's a movie adapted from a comic book for Chrissakes; but when Lois dies at the end, I get waterworks each and every time. Christopher Reeve's performance is just remarkable (I love that bit when he tenderly places her body on the ground and winces, as if afraid to hurt her even in death). The entire sequence is a tribute to what writers can achieve in a big-budget genre film if they remember a film's audience comprises human beings, not market analysts. Superman made me believe in these fictional characters by getting me to identify with them and care about what happens to them. Today, I think superhero films are out to get their audiences to have a relationship with the stunts, gadgetry, and special effects. .

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

I'd be remiss in praising Superman without making special

mention of the indispensable contributions of famed cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth

(Murder on the Orient Express, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Cabaret) and composer John Williams (Jaws, Star Wars, Close Encounters

of the Third Kind). A master of light with an eloquent eye for composition,

Unsworth gives Superman a distinctive

sheen (evident in the screencaps used here), its degree of impact made

all the more conspicuous by how significantly subsequent Superman films suffered due to their lack of visual distinction.

And what can I say about John William's epic Superman theme? Absolute perfection! It deftly strikes the right chord of nostalgia by recalling the classic TV show theme, yet feels like a wholly new take on those soaring themes from serials and adventure films of yesteryear. Williams' score is one of those real goosebump-inducing anthems that absolutely MAKES the film. As far as I'm concerned, John Williams is as responsible for Superman's success as Richard Donner.

And what can I say about John William's epic Superman theme? Absolute perfection! It deftly strikes the right chord of nostalgia by recalling the classic TV show theme, yet feels like a wholly new take on those soaring themes from serials and adventure films of yesteryear. Williams' score is one of those real goosebump-inducing anthems that absolutely MAKES the film. As far as I'm concerned, John Williams is as responsible for Superman's success as Richard Donner.

After 1980's Superman II (which I very much enjoyed), it's fair to say I haven't liked a single Superman incarnation—film or TV—since. I do intend seeing Man of Steel (2013) when it comes out on DVD*, although I admit, my expectations aren't very high.

*Update 2014: Watched Man of Steel and my jaw never left the floor, stunned as I was for how epic a miscalculation the whole costly enterprise was.

*Update 2014: Watched Man of Steel and my jaw never left the floor, stunned as I was for how epic a miscalculation the whole costly enterprise was.

So, the point of this post is that, despite my grousing, I really do "get it" when it comes to the public's fascination with comic book movies today. Even without needing to call them 'graphic novels." I appreciate that illustration is a valid narrative medium and doesn't instantly brand a work as lightweight or intended only for children.

It's natural to want to recapture the sense of wonder movies had for us as kids. And I can't think of a better reminder of that fact than Superman: The Movie.